THE FRENCH REVOLUTIONAY WARS

1792 -

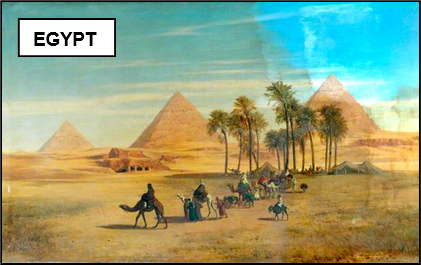

THE BATTLE OF THE PYRAMIDS 1798

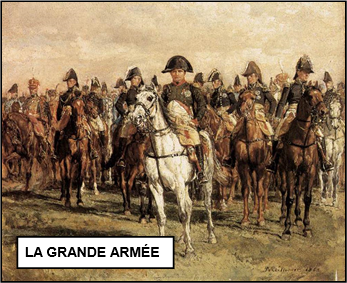

xxxxxThe Treaty of Campo Formio in July 1797 left only Great Britain at war with France. On his return to Paris, Napoleon rejected any idea of invading England, and proposed instead the capture of Egypt in order to threaten Britain’s overland route to India. The Directory, deeply concerned about Napoleon’s political ambitions, readily agreed to this plan. The French fleet arrived in Egypt in July 1798 after capturing the island of Malta. Alexandria was quickly seized and then, in the same month, the Egyptians were soundly beaten at the Battle of the Pyramids. In August, however, a British fleet commanded by Admiral Nelson attacked and destroyed the French squadron in Aboukir Bay and this Battle of the Nile left Napoleon’s army stranded in the Near East. After an unsuccessful invasion of Syria and a victory over the Egyptians at the Battle of Aboukir, Napoleon saw no future in staying. Learning that there was a political crisis in Paris, he secretly left and arrived in France in October 1799, prepared for high office.

Including:

The Rosetta Stone

xxxxxAs we have seen, following the Treaty of Campo Formio in

July 1797, only the British remained at war with France. Napoleon,

having returned to Paris after his brilliant military and diplomatic

campaign in Italy, was only too eager to take them on. The Directory

was in favour of an invasion of England, but

in February 1798 Napoleon ruled out such an undertaking until such

time as France had command of the sea. Instead, he proposed that he

occupy Egypt. This, he argued, apart from striking at Britain’s

wealth by threatening its overland route to India, would provide a

valuable bargaining counter in the inevitable peace settlement.

These were valid aims, though the romantic lure of Ancient Egypt

doubtless played some part in his proposal! The Directors willingly

agreed. Wary of Napoleon’s overriding ambition, they were only too

pleased to send him as far away as possible from the centre of

power!

xxxxxAs we have seen, following the Treaty of Campo Formio in

July 1797, only the British remained at war with France. Napoleon,

having returned to Paris after his brilliant military and diplomatic

campaign in Italy, was only too eager to take them on. The Directory

was in favour of an invasion of England, but

in February 1798 Napoleon ruled out such an undertaking until such

time as France had command of the sea. Instead, he proposed that he

occupy Egypt. This, he argued, apart from striking at Britain’s

wealth by threatening its overland route to India, would provide a

valuable bargaining counter in the inevitable peace settlement.

These were valid aims, though the romantic lure of Ancient Egypt

doubtless played some part in his proposal! The Directors willingly

agreed. Wary of Napoleon’s overriding ambition, they were only too

pleased to send him as far away as possible from the centre of

power!

xxxxxFor its part, Great Britain

had entered the war with France in February 1793, alarmed not only

at the execution of the Louis XVI but -

xxxxxIt was amid great secrecy that the French prepared a fleet at Toulon to take some 30,000 men to the Near East. It put to sea in May 1798, and the following month, having successfully evaded the British fleet that lay in wait, overwhelmed the Knights Hospitallers on Malta and occupied the island. It then made for Egypt and landed at Aboukir Bay on the first day of July. Napoleon stormed and occupied Alexandria the next day and then, wasting no time, moved on to Cairo, defeating the Mamluk leader Murad Bey at Shubrakhit en route.

xxxxxThe decisive engagement,

the so-

xxxxxOnce in control of Cairo, Napoleon attempted to get on

good terms with the inhabitants by declaring his sympathy with the

Moslem faith, and appointing Egyptians to share in the running of

the city. This met with little success. There was, in fact, much

opposition to French rule, and -

xxxxxOnce in control of Cairo, Napoleon attempted to get on

good terms with the inhabitants by declaring his sympathy with the

Moslem faith, and appointing Egyptians to share in the running of

the city. This met with little success. There was, in fact, much

opposition to French rule, and -

xxxxxThe next month the Sultan

of Turkey launched an attack to re-

xxxxxMeanwhile the

army he deserted survived for two years. In March 1801 British

troops arrived at Aboukir Bay and, soon afterwards, a British Indian

force landed at Qusayr on the coast of the Red Sea. Faced with such

opposition, plus an Ottoman invasion from Syria, the French army

admitted defeat. The Cairo garrison surrendered in June and the

French commander Menou, based at Alexandria, capitulated in the

September. Despite the French defeat -

xxxxxIncidentally, Napoleon had

regarded the French occupation of Egypt as a civilising venture,

aimed at rekindling the country’s ancient culture and prosperity. He

came as a “liberator”. Thus along with his military forces went a

large number of scholars and scientists to study the country’s past

and plan for its future. In 1799 there came into their possession a

slab of basalt dating from 196 BC (roughly 2 x 4 feet in size).

Discovered by a French army officer near the town of Rosetta

(today’s Rashid), it was inscribed with a piece of text written in

three versions -

xxxxxIncidentally, Napoleon had

regarded the French occupation of Egypt as a civilising venture,

aimed at rekindling the country’s ancient culture and prosperity. He

came as a “liberator”. Thus along with his military forces went a

large number of scholars and scientists to study the country’s past

and plan for its future. In 1799 there came into their possession a

slab of basalt dating from 196 BC (roughly 2 x 4 feet in size).

Discovered by a French army officer near the town of Rosetta

(today’s Rashid), it was inscribed with a piece of text written in

three versions -

Xxxxx…… This

“Rosetta Stone”,

as it came to be known, provided the means by which ancient Egyptian

inscriptions could be deciphered. However, as we shall see, this did

not come about until 1822 (G4), when a young French Egyptologist, Jean-

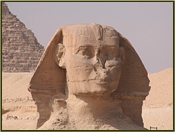

xxxxx…… But at the same time as

French scholars were preserving the Rosetta Stone because of its

historical significance, and creating an Institute for the study of ancient Egypt, French soldiers

were using the ancient Sphinx at Giza for target practice!

Comprising the figure of a recumbent lion with a human head, the

facial features of this huge monument are thought to be those of

King Khafre of the 3rd century BC. He probably had it built to guard

his pyramid, the second of the three constructed there. The musket

fire, probably done as a bit of fun, peppered the face and took off

the nose. ……

xxxxx…… But at the same time as

French scholars were preserving the Rosetta Stone because of its

historical significance, and creating an Institute for the study of ancient Egypt, French soldiers

were using the ancient Sphinx at Giza for target practice!

Comprising the figure of a recumbent lion with a human head, the

facial features of this huge monument are thought to be those of

King Khafre of the 3rd century BC. He probably had it built to guard

his pyramid, the second of the three constructed there. The musket

fire, probably done as a bit of fun, peppered the face and took off

the nose. ……

xxxxx……

One of the scholars who accompanied Napoleon on his expedition to

Egypt was the French applied mathematician Joseph

Fourier (1768-

Acknowledgements

Egypt: by the German painter

August Albert Zimmermann (1808-

G3b-