xxxxxAs we have seen, the enormous suffering of the Irish people during the Great Potato Famine of 1845 (Va) brought violence in its wake. The Fenian Uprising of 1867 (Vb), for example, though ending in failure, was an all-

IRELAND AND THE PHOENIX PARK MURDERS

MAY 1882 (Vc)

Acknowledgements

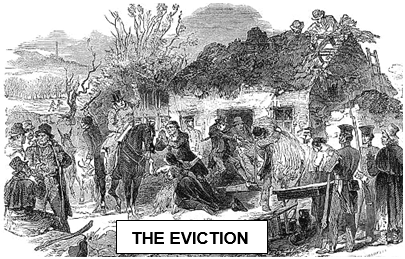

Famine: wood engraving, published in The London Illustrated News, 1849, artist unknown. Davitt: by the photographic studio of Bradley & Rulofson, San Francisco, c1880 – Library of Congress, Washington. Eviction: by the British artist Robert Thomas Landells (1833-

xxxxxAs we have seen, whilst the British government had taken some measures to alleviate the enormous suffering of the Irish people during the Great Potato Famine of 1845 (Va), their efforts had proved too little and too late. As a result, resentment against the British -

xxxxxAs we have seen, whilst the British government had taken some measures to alleviate the enormous suffering of the Irish people during the Great Potato Famine of 1845 (Va), their efforts had proved too little and too late. As a result, resentment against the British -

xxxxxBut the Land Act of 1870 was extremely limited in its scope and, in fact, did very little to alleviate the current suffering of the tenant farmers. The early years of the1870s saw the “Long Depression”, a period characterized by low prices, bad weather and poor harvests. And imports of wheat from new sources, such as the United States and the Ukraine, and refrigerated meat from Argentina and Australia made matters worse. Many tenant farmers fell into arrears with their rents and, having no legal rights, found themselves at the mercy of their English landlords. The result was the so-

xxxxxThexIrish politician Charles Stewart Parnell, founder of the Irish Parliamentary Party, was elected the League’s president and, together with other radicals -

xxxxxThexIrish politician Charles Stewart Parnell, founder of the Irish Parliamentary Party, was elected the League’s president and, together with other radicals -

xxxxxThe provocative stance taken by the League -

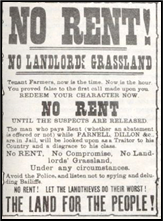

xxxxxThis Land Act went a long way to improving the rights of the tenant farmer, but Parnell considered that it did not go far enough. It made no provision to help tenants in distress, and it excluded tenants who were in arrears with their rent. He now began to make speeches violently denouncing the government’s policy towards Ireland, and with his encouragement the civil disobedience continued. As a result, he was held responsible for the violence and arrested in October 1881. Along with othe r prominent members of the Land League, he was imprisoned in Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin for “sabotaging the Land Act”. From there, however, Parnell issued a “No rent manifesto”, calling for a general strike of tenant farmers until the members of the League had been released. It was only partially successful, but the widespread unrest continued and persuaded the government that a settlement had to be reached. InxAprilx1882 Gladstone negotiated an agreement with Parnell -

r prominent members of the Land League, he was imprisoned in Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin for “sabotaging the Land Act”. From there, however, Parnell issued a “No rent manifesto”, calling for a general strike of tenant farmers until the members of the League had been released. It was only partially successful, but the widespread unrest continued and persuaded the government that a settlement had to be reached. InxAprilx1882 Gladstone negotiated an agreement with Parnell -

xxxxxThe agreement had its dissenters. In the Land League, Michel Davitt and a number of other members were strongly opposed to the “treaty”, whilst on the government side William Edward Forster, the man who had spearheaded the Coercion Act, resigned in protest. He was replaced by Lord Frederick Charles Cavendish, and he was at once despatched to Ireland with the clear intention of achieving Gladstone’s mission -

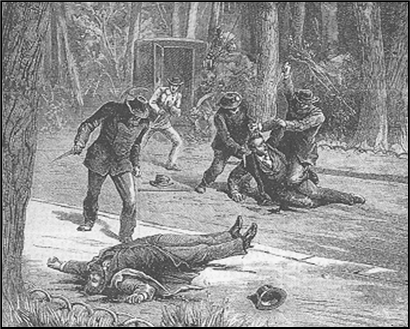

xxxxxOne such society was the so-

xxxxxThexmurderers were traced and brought to justice in the Spring of 1883. With the assistance of three who turned Queen’s evidence -

xxxxxThexmurderers were traced and brought to justice in the Spring of 1883. With the assistance of three who turned Queen’s evidence -

xxxxxThe Phoenix Park murders shocked Victorian England, and was followed by a wave of terrorism. The Gladstone’s government responded with the Prevention of Crimes Act, which suspended trial by jury, banned public meetings, and gave the police exceptional powers for three years. And the army was called in to reinforce the forces of law and order. Faced with bitterness and distrust on both sides, Gladstone now began to see home rule as the only solution to pacify Ireland and complete his mission. For his part, Parnell roundly condemned the murders and in October 1882, in order to broaden his campaign, he replaced the Irish National Land League, suppressed by the government, with the Irish National League. This organisation -

xxxxxThe Phoenix Park murders shocked Victorian England, and was followed by a wave of terrorism. The Gladstone’s government responded with the Prevention of Crimes Act, which suspended trial by jury, banned public meetings, and gave the police exceptional powers for three years. And the army was called in to reinforce the forces of law and order. Faced with bitterness and distrust on both sides, Gladstone now began to see home rule as the only solution to pacify Ireland and complete his mission. For his part, Parnell roundly condemned the murders and in October 1882, in order to broaden his campaign, he replaced the Irish National Land League, suppressed by the government, with the Irish National League. This organisation -

xxxxxThe climate for political change within Ireland came with the results of the general election in November 1885. The Irish Nationalists gained a commanding position. Their 86 seats virtually equated to the Liberal majority over the Conservatives and this gave them the balance of power in Parliament. A minority Conservative government took office, but the turning point came in January 1886, when the Conservative prime minister, Lord Salisbury, a man opposed to the idea of home rule, announced that his government intended to re-

xxxxxThe climate for political change within Ireland came with the results of the general election in November 1885. The Irish Nationalists gained a commanding position. Their 86 seats virtually equated to the Liberal majority over the Conservatives and this gave them the balance of power in Parliament. A minority Conservative government took office, but the turning point came in January 1886, when the Conservative prime minister, Lord Salisbury, a man opposed to the idea of home rule, announced that his government intended to re-

xxxxxIncidentally, the word “boycotting” took its name from a Captain Charles Cunningham Boycott, a land agent for an absentee landlord in County Mayo. He refused to lower the rents of his tenant farmers, and evicted those who fell into arrears, and so, by way of retaliation the local community ostracised him and his family, refusing to harvest crops on the estate or supply food and other essentials. So effective was this strategy that Boycott and his family were forced to return to England, the Irish acquired a new and effective “weapon” in the Land War, and the English language took on a new word.

Vc-

xxxxxThe Irish nationalist politician Charles Stewart Parnell (1846-

xxxxxThe Irish nationalist politician Charles Stewart Parnell (1846-

xxxxxThe Irish nationalist politician Charles Stewart Parnell (1846-

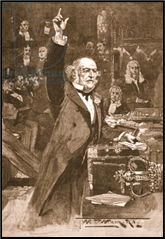

xxxxxAs we have seen, Parnell played a prominent and active part in Ireland’s troubled history during the 1880s. As president of the National Irish Land League, formed in 1879, he led the campaign to alleviate the suffering of the tenant farmer. Indeed, his fiery oratory in their support stirred up such violence in the Land War that he was sent to prison in October 1881, along with other League members. However, he was quickly released when the British government, led by William Gladstone, realized that only he -

xxxxxMeanwhile at Westminster, as leader of the Irish party, Parnell skilfully employed tactics to disrupt the work of the House of Commons in order to keep the severity of the Irish Question in the pubic eye. In the election of November 1885, however, his party gained the balance of power in parliament and the voting advantage that went with it. As a result, in January 1886 he threw his party’s support behind Gladstone’s Liberals and, as we shall see, paved the way for the first Irish Home Rule Bill in April 1886.

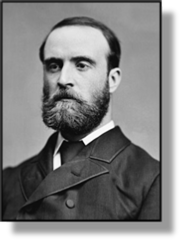

xxxxxDespite the failure of Gladstone’s bill and his consequent defeat, Parnell continued to work for home rule. He kept up his support for the tenant famers, and he met Gladstone on two occasions to plan a second attempt at legislation. In 1887, however, his career was seriously threatened when The Times of London published letters purportedly written by him in support of the Phoenix Park murders. These letters were eventually found to be forgeries and by a special commission of enquiry he was completely exonerated in February 1889, but there was no way out of the scandal that engulfed him ten months later. It was then that Captain William O’Shea, formerly one of his staunchest supporters, filed for divorce and cited Parnell as co-

xxxxxDespite the failure of Gladstone’s bill and his consequent defeat, Parnell continued to work for home rule. He kept up his support for the tenant famers, and he met Gladstone on two occasions to plan a second attempt at legislation. In 1887, however, his career was seriously threatened when The Times of London published letters purportedly written by him in support of the Phoenix Park murders. These letters were eventually found to be forgeries and by a special commission of enquiry he was completely exonerated in February 1889, but there was no way out of the scandal that engulfed him ten months later. It was then that Captain William O’Shea, formerly one of his staunchest supporters, filed for divorce and cited Parnell as co-

xxxxxThis revelation of adultery brought an end to Parnell’s political career and it split the party he had for so long worked hard to build. He made strenuous attempts to reunite the nationalists, but the majority of party members and Catholic bishops remained strongly against him. In this fight for survival his health quickly deteriorated, and he died of rheumatic fever in October 1891 at the age of 45. Over 200,000 people attended his funeral in Dublin to pay homage to a man who, more than any other politician of his time, had worked constantly in the service of his country. Today a memorial to him, erected in 1911, stands at the north end of O’Connell Street in Dublin.

Including:

Charles Stewart Parnell