THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION, PHILADELPHIA 1787 (G3b)

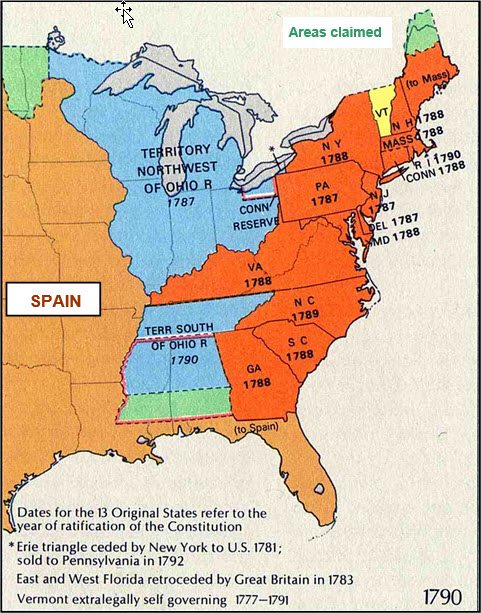

xxxxxThe Americans won their independence at the Peace of Paris in 1783 (G3a). Their next task was to win the peace. At the Second Continental Congress, called in 1775, it soon became clear that the individual states were anxious to keep their independence. The Articles of Confederation then drawn up and ratified in 1781 gave Congress very limited authority. States issued their own money, raised trade barriers, and had border disputes with their neighbours. The Convention which met at Philadelphia in 1787 aimed to safeguard the rights of individual states, whilst establishing a central authority to govern the Union. After much bitter debate a constitution was agreed -

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Peace of Paris in 1783 (G3a) was a military triumph for the colonists, -

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Peace of Paris in 1783 (G3a) was a military triumph for the colonists, -

xxxxxAs a consequence, the Articles of Confederation which were eventually drawn up at the Continental Congress were not ratified by all the states until 1781. Even then, they provided for a Congress with limited authority, and one that could not enforce its laws if individual states chose to ignore them. Indeed, one article actually reserved sovereignty to the individual states. Furthermore, as the war approached its end, many states reverted to all the trappings of their former independence, making their own treaties, providing for their own defence, and virtually ignoring the confederation government. Border disputes with neighbouring states often led to bloodshed and the raising of trade barriers.

xxxxxNot surprisingly, there were many commentators in England as well as America who felt that the differences that divided the thirteen former colonies were far too deep and diverse to allow of a centralised government, whatever form it might be given. General George Washington himself described the Articles as “little more than the shadow without the substance”. He, along with other Nationalists, called for something to be done before the opportunity of nationhood was lost for ever. Andxan event which highlighted this need for urgency was Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts (illustrated). Led by Captain Daniel Shays, this broke out in 1786 as a protest against the high taxes levied against the farming community there. Well over a thousand farmers and farm labourers took part in the revolt. It was put down the following year by an army raised in the state, but it sent shock waves through the entire country, and made still more pressing the establishment of an effective central authority.

xxxxxNot surprisingly, there were many commentators in England as well as America who felt that the differences that divided the thirteen former colonies were far too deep and diverse to allow of a centralised government, whatever form it might be given. General George Washington himself described the Articles as “little more than the shadow without the substance”. He, along with other Nationalists, called for something to be done before the opportunity of nationhood was lost for ever. Andxan event which highlighted this need for urgency was Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts (illustrated). Led by Captain Daniel Shays, this broke out in 1786 as a protest against the high taxes levied against the farming community there. Well over a thousand farmers and farm labourers took part in the revolt. It was put down the following year by an army raised in the state, but it sent shock waves through the entire country, and made still more pressing the establishment of an effective central authority.

xxxxxIt was against this background that in May 1787 a Constitutional Convention (illustrated) was convened at Philadelphia in an attempt to find a form of government which would safeguard the rights of individual states whilst, at the same time, providing a central authority charged with maintaining law and order, defending the nation against external threat, and preserving the liberty of its individual citizens. At first, the 51 delegates tried to amend the Articles to fit these needs, but finding the task impossible, drafted an entirely new document. Washington presided over the proceedings, and the result was a federal constitution wherein both the national and state governments had their own judicial powers within a federal framework. The thorny question of representation was overcome by a compromise, though not before much lengthy and bitter argument. Two houses were established: a lower house, to be known as the House of Representatives, to be elected according to population, and an upper house, the Senate, in which all the states would have equal representation. As in Britain, there was to be a clear division between the three branches of government: the executive, the legislative and the judiciary. This central authority, charged with the promotion of “the general welfare”, had the right to levy taxes and duties, and to use force to maintain “a republican form of government”.

known as the House of Representatives, to be elected according to population, and an upper house, the Senate, in which all the states would have equal representation. As in Britain, there was to be a clear division between the three branches of government: the executive, the legislative and the judiciary. This central authority, charged with the promotion of “the general welfare”, had the right to levy taxes and duties, and to use force to maintain “a republican form of government”.

xxxxxBut unlike the British, the Americans committed their constitution to paper, defining in written charters the freedoms of the individual and of the press in a republican state. These were summarised in just seven articles, but two years later a Bill of Rights containing ten amendments was added to define more clearly a citizen’s rights. This constitution did not mark an end to the troubled years, very far from it, but the former colonists, having won their independence, had now achieved their second vital need, the making on paper at least of a workable form of government. The constitution was adopted in 1788, albeit by the narrowest of votes in New York and Virginia, and the Americans had created their state.

second vital need, the making on paper at least of a workable form of government. The constitution was adopted in 1788, albeit by the narrowest of votes in New York and Virginia, and the Americans had created their state.

xxxxxThere was clearly only one candidate for the first President. George Washington, and he alone, commanded the respect of all the rival regional factions which had ranted and raved against each other during the bitter disputes over the constitution. And in Europe, too, he was held in the highest esteem as a man of courage and integrity. He himself was hoping to retire once the constitution had been ratified, but, as we shall see, in April 1789 he was unanimously elected President of the United States, the only president to be so honoured. He took the oath of office later that month.

xxxxxThere was clearly only one candidate for the first President. George Washington, and he alone, commanded the respect of all the rival regional factions which had ranted and raved against each other during the bitter disputes over the constitution. And in Europe, too, he was held in the highest esteem as a man of courage and integrity. He himself was hoping to retire once the constitution had been ratified, but, as we shall see, in April 1789 he was unanimously elected President of the United States, the only president to be so honoured. He took the oath of office later that month.

Acknowledgements

Rebellion: date and artist unknown. Convention: by the American artist Howard Chandler Christy (1873-

G3b-