xxxxxThe

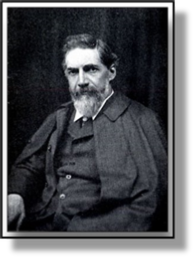

English archaeologist Sir Flinders Petrie spent most of his life in

the Middle East. Starting in 1880, he studied the pyramids at Giza

and then excavated some thirty sites in Egypt. Among his important

discoveries were the temple at Tanis (1884); the Greek trading posts of Naukratis and Daphnae; the

famous Fayum mummy portraits at Hawara; the beautiful frescoes and

pavements at Amarna; and the Merneptah Stele,

a granite tablet which contained the earliest-known Egyptian

reference to the land of Israel. He carried out extensive

excavations in Palestine from 1927 to 1938 at sites such as

Tell el-Jemmeh and Tel el-Farah. He was knighted in

1823 for his services to archaeology, not only for his important

findings, but also for his contribution to methodology. His

painstaking recording and his method of establishing the history of

a site by the examination of pottery fragments, set new standards in

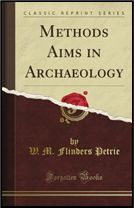

archaeology. He wrote nearly one hundred books, including The

Method and Aims of Archaeology

and Seventy Years in Archaeology.

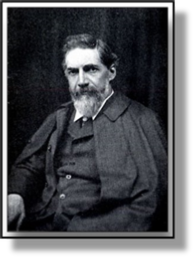

SIR FLINDERS PETRIE 1853 -

1942 (Va, Vb,

Vc, E7, G5, G6)

Acknowledgements

Petrie: 1903,

photographer unknown – The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology,

London. Findings: The Petrie Museum of

Egyptian Archaeology, London, contains over 80,000 objects. Pitt

Rivers: 1860-1869, artist unknown – Pitt

Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, England.

xxxxxThe English archaeologist and Egyptologist Sir

Flinders Petrie spent much of his working life in Egypt and The

Levant. Over a period of forty years, starting in 1880, he studied

the pyramids at Giza and excavated some thirty sites -

including those at Tanis, Naukratis, Amarna and Abydos. During

this time he made a valuable contribution to the methodology of

field excavation, and pioneered a valuable dating system based on

the identification of the pottery associated with various ancient

cultures. From 1927 to 1938 he worked in Palestine, notably at the

ancient city of Lachish. He was professor of Egyptology at the

University of London from 1892 to 1933 - the first chair in

this subject - and in 1894 he founded The Egyptian Research

Account, an institution which became the British School of

Archaeology in Egypt in 1905 and remained in being until 1954.

Among his books - nearly one hundred in number - are The Method and Aims of Archaeology

of 1904, and Seventy Years in Archaeology,

published in 1931.

xxxxxThe English archaeologist and Egyptologist Sir

Flinders Petrie spent much of his working life in Egypt and The

Levant. Over a period of forty years, starting in 1880, he studied

the pyramids at Giza and excavated some thirty sites -

including those at Tanis, Naukratis, Amarna and Abydos. During

this time he made a valuable contribution to the methodology of

field excavation, and pioneered a valuable dating system based on

the identification of the pottery associated with various ancient

cultures. From 1927 to 1938 he worked in Palestine, notably at the

ancient city of Lachish. He was professor of Egyptology at the

University of London from 1892 to 1933 - the first chair in

this subject - and in 1894 he founded The Egyptian Research

Account, an institution which became the British School of

Archaeology in Egypt in 1905 and remained in being until 1954.

Among his books - nearly one hundred in number - are The Method and Aims of Archaeology

of 1904, and Seventy Years in Archaeology,

published in 1931.

xxxxxPetrie was

born in Charlton, near Greenwich, now part of South-East

London. His father was a civil engineer and surveyor, and his

mother had a knowledge of fossils and natural minerals. Both

encouraged their son to take an interest in archaeology and all

things ancient. He was largely self-taught, but his father

gave him a good grounding in surveying, and as a young man he

travelled across the country visiting ancient sites. He became

particularly interested in Stonehenge, and after a close study of

this prehistoric monument, he set out his findings in a work

entitled Stonehenge: Plans, Description and

Theories, published in 1880. This proved highly valuable

as a basis for further research. And it was in that same year that

he made his first visit to Egypt and, living in a cave at Giza,

began a systematic survey of the Great Pyramid and the two smaller

pyramids nearby. For some two years, working slowly and

meticulously, he sought to understand their geometry and the

method by which they were built. Much of his data, particularly

regarding the pyramid plateaux, remain valid to this day.

xxxxxHis work at Giza marked the beginning of forty years

of dedicated work which took him all over Egypt and much of

Palestine. During this long period of painstaking research he made

a number of outstanding discoveries. In the Nile Delta, for

example, he carried out diggings at the great temple in Tanis in 1884, and it was there that he discovered

pieces of a colossal statue of Ramses II, king of Egypt from 1303

to 1213 BC. Then over the next two years he unearthed the ancient

fortress towns of Naukratis and Daphnae. It was during these

excavations that, having uncovered fragments of painted pottery,

he recognised the civilization to which they belonged, and was

able to prove that both these settlements were ancient Greek

trading posts. This idea of studying and comparing pieces of

pottery at various levels of an excavation, pioneered by Petrie,

became a valuable means of reconstructing the history of an area.

Pottery discovered at Naukratis assisted in tracing the early

development of the Greek alphabet, and threw light on the trading

carried out by a number of Greek states around the 6th century BC.

At Daphnae he uncovered a massive fortress built by Pharaoh

Psamtik I a century earlier.

xxxxxHis work at Giza marked the beginning of forty years

of dedicated work which took him all over Egypt and much of

Palestine. During this long period of painstaking research he made

a number of outstanding discoveries. In the Nile Delta, for

example, he carried out diggings at the great temple in Tanis in 1884, and it was there that he discovered

pieces of a colossal statue of Ramses II, king of Egypt from 1303

to 1213 BC. Then over the next two years he unearthed the ancient

fortress towns of Naukratis and Daphnae. It was during these

excavations that, having uncovered fragments of painted pottery,

he recognised the civilization to which they belonged, and was

able to prove that both these settlements were ancient Greek

trading posts. This idea of studying and comparing pieces of

pottery at various levels of an excavation, pioneered by Petrie,

became a valuable means of reconstructing the history of an area.

Pottery discovered at Naukratis assisted in tracing the early

development of the Greek alphabet, and threw light on the trading

carried out by a number of Greek states around the 6th century BC.

At Daphnae he uncovered a massive fortress built by Pharaoh

Psamtik I a century earlier.

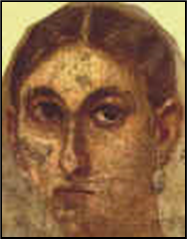

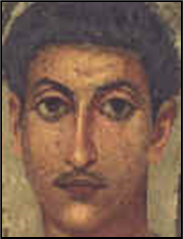

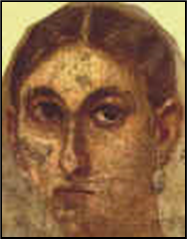

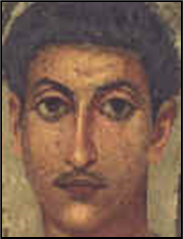

xxxxxLater,

while working in the Al-Fayum region in the late 1880s, he

found jewellery belonging to a princess of the 12th dynasty

(around 1880 BC) at Illahun, and at Gurob he unearthed a large

number of papyri and Aegean pottery that confirmed dates relating

to the Mycenaean and other ancient Greek civilizations. But his

greatest find in this area (at Hawara), was the discovery of the

famous Fayum mummy portraits, some eighty in number. Painted on

wooden boards and depicting the face of a single person (sometimes

the head and shoulders) they were placed over the faces of the

bodies mummified for burial. Dating from the Roman occupation of

Egypt - approximately the first three centuries AD -

they had become detached from their mummies and were in a

remarkably good state of preservation (two

Illustrated above).

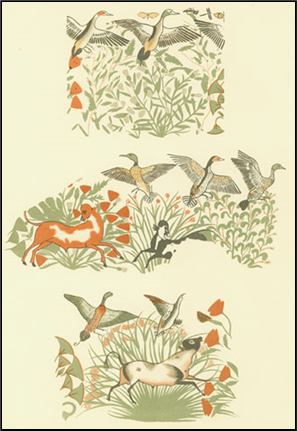

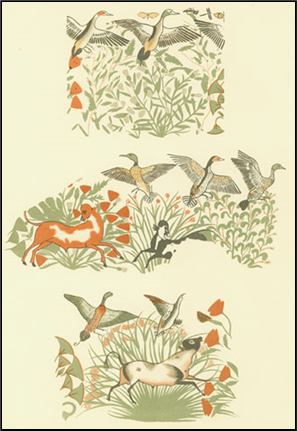

xxxxxIt was while working at Tell el-Amarna in 1891,

excavating the city of Akhenaton (the ruler of Egypt from 1353 to

1336 BC) that he found several beautiful frescoes and three

painted pavements in the King’s House and the Harem Quarter of the

Great Palace. The pavement scenes, one of which was 300ft square,

were painted on gypsum plaster and depicted plants, animals and

hunting scenes. These were so “astonishingly fresh and clear”, as

he recorded at the time, that he built a structure over the top of

them to preserve them for posterity. Sadly, the tourists these

treasures attracted trampled down nearby crops and the local

peasant farmers smashed up the pavements to put end to their

unwelcome visitors! It is only through Petrie’s documentation of

these frescoes and pavements, recoded in black and white and

colour drawings, that provides an idea of their original state. On

the left are the designs on the painted gypsum pavements, and on

the right is a wall painting, placed above a reconstruction of the

painted

xxxxxIt was while working at Tell el-Amarna in 1891,

excavating the city of Akhenaton (the ruler of Egypt from 1353 to

1336 BC) that he found several beautiful frescoes and three

painted pavements in the King’s House and the Harem Quarter of the

Great Palace. The pavement scenes, one of which was 300ft square,

were painted on gypsum plaster and depicted plants, animals and

hunting scenes. These were so “astonishingly fresh and clear”, as

he recorded at the time, that he built a structure over the top of

them to preserve them for posterity. Sadly, the tourists these

treasures attracted trampled down nearby crops and the local

peasant farmers smashed up the pavements to put end to their

unwelcome visitors! It is only through Petrie’s documentation of

these frescoes and pavements, recoded in black and white and

colour drawings, that provides an idea of their original state. On

the left are the designs on the painted gypsum pavements, and on

the right is a wall painting, placed above a reconstruction of the

painted dado.

dado.

xxxxxBut

Petrie’s richest find historically was his discovery of the Merneptah Stele. Found at the ancient city

of Thebes (near today’s Luxor) in 1896, this upright stone tablet,

made in black granite and over ten feet in height, contained an

inscription on its reverse side by the Ancient Egyptian King

Merneptah, who reigned from 1213 to 1204 BC. For the most part it

recorded his successful defence of Egypt against a powerful

invasion by the Libyans, but it also contained what is thought to

be the earliest-known Egyptian reference to the land of

Israel (I.si.ri,ar ). For that reason

the tablet is often referred to as the Israel

Stele. The discovery made newspaper headlines across the

world. And while working at Luxor he found a statue of Merneptah

himself (the son and successor of Ramses II) and another,

beautifully sculptured stele depicting a battle between Amenhotep

III and the Nubians and Syrians.

xxxxxPetrie

carried out extensive excavations in Palestine from 1927 to 1938,

particularly at the ancient city of Lachish (now Tell ed Duweir in

Israel) and at the sites of Tell el-Jemmeh, Tell el-Farah

and Tell el-Ajjul, but his first visit to Palestine was in

1890. It was then, during a six-week stay at Tell el-Hesi,

that, applying his principle of sequence dating (also known as

“seriation”), he made his first stratigraphic study - an

examination of successive levels - and produced a chronology

of this ancient hill site. He then went on to survey a number of

tombs in the valley of Wadi al-Rababah south of Jerusalem

which dated from the Iron Age and the Roman period. His work at

Tell el-Hesi was continued from 1894 to 1897 by one of

Petrie’s students, the American archaeologist Frederick

J. Bliss (1857-1939). Illustrated

here are some of Petrie’s findings:

Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc

xxxxxPetrie was

knighted in 1923 in recognition of his life-time work in the

service of archaeology, not only for the many important

discoveries he made in the Middle East, but also because of his

contribution to methodology. His painstaking recording of all the

results of his extensive surveying and excavation; the new and

enduring method he introduced to establish the chronology of a

site, based on the examination of pottery fragments; and the

meticulous care he took when carrying out the inspection of a

site, set new standards in archaeology. It was this highly

professional approach, together with his innovations, that earned

him the title Father of Modern Archaeology. Together with Lady

Petrie he spent the last years of his life in Jerusalem at the

American School of Oriental Research. He died of a stroke in July

1942 and was buried in the Protestant cemetery on Mount Zion.

xxxxxHe wrote 97 books and over 850 articles on his

research and discoveries. His Methods and Aims

in Archaeology, published in 1904, was a particularly

valuable work in which he emphasised the importance of a

systematic approach to excavation, including the value of

photography in the accurate recording of data.

xxxxxHe wrote 97 books and over 850 articles on his

research and discoveries. His Methods and Aims

in Archaeology, published in 1904, was a particularly

valuable work in which he emphasised the importance of a

systematic approach to excavation, including the value of

photography in the accurate recording of data.

xxxxxIncidentally, Petrie returned to the Al-Fayum region in 1910

and added to his store of panel portraits. Today some 900 of these

panel paintings are in existence, the majority from the Fayum

region, and among those museums with a number on show are the

British Museum, The Louvre in Paris, and the Metropolitan Museum

of Art in New York. ……

xxxxx…… In the 1890s Petrie trained a young archaeologist

named Howard Carter, the man who in November 1922 discovered the

tomb of the young king Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings at

Thebes. In 1913 Petrie sold his large collection of Egyptian

antiquities to University College London, where it is now housed

in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. ……

xxxxx…… ThexEnglish archaeologist Percy Gardner (1846-1937)

served as field assistant to Petrie while he was working in Egypt,

and his brother Ernest Gardner (1862-1939), also an archaeologist, continued

Petrie’s research at Naukratis in 1885, and was Director of the

British School of Archaeology at Athens from 1887 to 1895. ……

xxxxx…… On his death in 1942 Petrie donated his brain to the

Royal College of Surgeons in London to

assist in research, but it was during the Second World War and the

German advance towards Egypt delayed its despatch. At one time it

was thought to have been lost in transit, but it eventually

reached its destination and is now preserved in a large glass jar.

……

xxxxx…… Petrie - full name Matthew Flinders Petrie -

was named after his maternal grandfather, Matthew Flinders, the

English navigator who circumnavigated Australia in 1801. ……

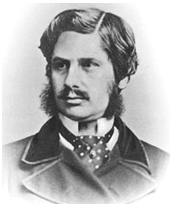

xxxxx…… Itxwas

around this time that the amateur archaeologist Augustus

Pitt Rivers (1827-1900), a former

general in the British army, began investigating ancient sites in

his large estate in Cranbourne Chase, Dorset, England. Like

Petrie, he carefully measured every finding and kept meticulous

records to show where each was found. The excavated material was

sent to Salisbury Museum, and his ethnological collection, some

20,000 items, made up the basis of the Pitt-Rivers Museum in

Oxford. In 1883 he was appointed the country’s first inspector of

ancient monuments.

xxxxx…… Itxwas

around this time that the amateur archaeologist Augustus

Pitt Rivers (1827-1900), a former

general in the British army, began investigating ancient sites in

his large estate in Cranbourne Chase, Dorset, England. Like

Petrie, he carefully measured every finding and kept meticulous

records to show where each was found. The excavated material was

sent to Salisbury Museum, and his ethnological collection, some

20,000 items, made up the basis of the Pitt-Rivers Museum in

Oxford. In 1883 he was appointed the country’s first inspector of

ancient monuments.

xxxxxThe English archaeologist and Egyptologist Sir

Flinders Petrie spent much of his working life in Egypt and The

Levant. Over a period of forty years, starting in 1880, he studied

the pyramids at Giza and excavated some thirty sites -

xxxxxThe English archaeologist and Egyptologist Sir

Flinders Petrie spent much of his working life in Egypt and The

Levant. Over a period of forty years, starting in 1880, he studied

the pyramids at Giza and excavated some thirty sites -

xxxxxHis work at Giza marked the beginning of forty years

of dedicated work which took him all over Egypt and much of

Palestine. During this long period of painstaking research he made

a number of outstanding discoveries. In the Nile Delta, for

example, he carried out diggings at the great temple in Tanis in 1884, and it was there that he discovered

pieces of a colossal statue of Ramses II, king of Egypt from 1303

to 1213 BC. Then over the next two years he unearthed the ancient

fortress towns of Naukratis and Daphnae. It was during these

excavations that, having uncovered fragments of painted pottery,

he recognised the civilization to which they belonged, and was

able to prove that both these settlements were ancient Greek

trading posts. This idea of studying and comparing pieces of

pottery at various levels of an excavation, pioneered by Petrie,

became a valuable means of reconstructing the history of an area.

Pottery discovered at Naukratis assisted in tracing the early

development of the Greek alphabet, and threw light on the trading

carried out by a number of Greek states around the 6th century BC.

At Daphnae he uncovered a massive fortress built by Pharaoh

Psamtik I a century earlier.

xxxxxHis work at Giza marked the beginning of forty years

of dedicated work which took him all over Egypt and much of

Palestine. During this long period of painstaking research he made

a number of outstanding discoveries. In the Nile Delta, for

example, he carried out diggings at the great temple in Tanis in 1884, and it was there that he discovered

pieces of a colossal statue of Ramses II, king of Egypt from 1303

to 1213 BC. Then over the next two years he unearthed the ancient

fortress towns of Naukratis and Daphnae. It was during these

excavations that, having uncovered fragments of painted pottery,

he recognised the civilization to which they belonged, and was

able to prove that both these settlements were ancient Greek

trading posts. This idea of studying and comparing pieces of

pottery at various levels of an excavation, pioneered by Petrie,

became a valuable means of reconstructing the history of an area.

Pottery discovered at Naukratis assisted in tracing the early

development of the Greek alphabet, and threw light on the trading

carried out by a number of Greek states around the 6th century BC.

At Daphnae he uncovered a massive fortress built by Pharaoh

Psamtik I a century earlier.

xxxxxIt was while working at Tell el-

xxxxxIt was while working at Tell el- dado.

dado.  xxxxxHe wrote 97 books and over 850 articles on his

research and discoveries. His Methods and Aims

in Archaeology, published in 1904, was a particularly

valuable work in which he emphasised the importance of a

systematic approach to excavation, including the value of

photography in the accurate recording of data.

xxxxxHe wrote 97 books and over 850 articles on his

research and discoveries. His Methods and Aims

in Archaeology, published in 1904, was a particularly

valuable work in which he emphasised the importance of a

systematic approach to excavation, including the value of

photography in the accurate recording of data.

xxxxx…… Itxwas

around this time that the amateur archaeologist Augustus

Pitt Rivers (1827-

xxxxx…… Itxwas

around this time that the amateur archaeologist Augustus

Pitt Rivers (1827-