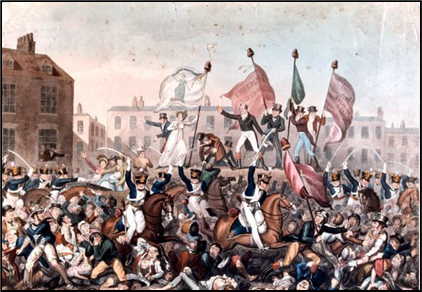

xxxxxIn a period of severe economic depression, a meeting of some 60,000, held in St. Peter’s Fields, Manchester, to demand parliamentary reform, was broken up by local cavalry. Eleven people were killed and 500 wounded. The ring leaders were imprisoned, and the Government later passed the Six Acts to provide greater powers for the suppression of political radicalism. The event, which took place in August 1819, came to be known as the Peterloo Massacre, an ironic reference to the Battle of Waterloo, fought four years earlier. The military action was widely condemned, but this had no immediate effect.

THE PETERLOO MASSACRE 1819 (G3c)

Acknowledgements

Peterloo: published the following month by the social reformer Richard Carlile (1790-

xxxxxThe Peterloo Massacre, as it came to be called, took place in Manchester, England, in August 1819, when an open-

xxxxxThe Peterloo Massacre, as it came to be called, took place in Manchester, England, in August 1819, when an open-

xxxxxThe event must be seen against a background of general discontent. The conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars was followed in Britain by a period of severe economic depression, and this gave rise to a growing demand for political and social reform. In agriculture, for example, landowners, by supporting the passing of the Corn Law of 1815 -

xxxxxThe meeting in St. Peter’s Field was planned as the largest of a series of rallies held in Manchester during 1819 to demand political reform and to protest against rising food prices, aggravated by the Corn Law of 1815. A large crowd of some 60,000 attended the meeting, including a large number of women and children, and the meeting was presided over by the radical leader Henry Hunt. None of the protestors was armed, and the gathering was completely peaceful, but the local magistrates, alarmed at the size of the gathering -

xxxxxThe meeting in St. Peter’s Field was planned as the largest of a series of rallies held in Manchester during 1819 to demand political reform and to protest against rising food prices, aggravated by the Corn Law of 1815. A large crowd of some 60,000 attended the meeting, including a large number of women and children, and the meeting was presided over by the radical leader Henry Hunt. None of the protestors was armed, and the gathering was completely peaceful, but the local magistrates, alarmed at the size of the gathering -

xxxxxSoon after the event the then Home Secretary, Viscount Sidmouth, sent a letter to congratulate the Manchester magistrates on their timely action. He assured them that the king had derived “great satisfaction” from the way they had preserved “public tranquillity”. Shortly afterwards Lord Liverpool’s Tory administration passed the Six Acts. These gave greater powers for the suppression of political radicalism so as to ensure that such a demonstration did not happen again. As for the organisers of the Manchester meeting, and the speakers who took part in it, they were charged with “assembling with unlawful banners at an unlawful meeting for the purpose of exciting discontent”. Five were sent to prison.

xxxxxBut whilst the government supported the military action taken in Manchester, there was widespread criticism of the authorities and the military. Meetings were held in protest, and the event was given critical coverage, especially in Manchester and London. One of the leaders, a journalist named James Wroe (1788-

Including:

Henry “Orator” Hunt

and Sir Francis Burdett

G3c-

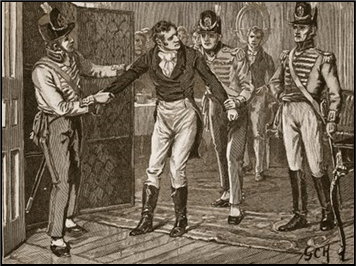

xxxxxAmong those arrested and imprisoned was the main speaker at the meeting, Henry “Orator” Hunt. His speech on parliamentary reform earned him two years and six months in jail. A radical reformer and a skilled orator, he became a member of parliament in 1830, and played a part in the passing of the Reform Act of 1832, legislation which widened the franchise.

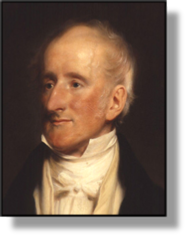

xxxxxAnd another man who was given a prison sentence for speaking his mind on the Peterloo Massacre was the English politician Sir Francis Burdett (1770-

xxxxxAnd another man who was given a prison sentence for speaking his mind on the Peterloo Massacre was the English politician Sir Francis Burdett (1770-

xxxxxThen on the 22nd August 1819, a few days after the protest meeting, he launched a blistering attack upon the government’s handling of the affair. In a letter addressed to his constituents and subsequently published, he spoke of his shame, grief and indignation at the “blood spill at Manchester”. Was this then, he asked, why England, the land of freedom, had a standing army in peace time, to kill unarmed, unresisting men and women? This was nothing short of an “unparalleled and barbarous outrage”. But at the Leicester Assizes in March the following year, the judge saw the letter as calculated to do “infinite mischief”. He was found guilty of seditious libel, fined £2,000, and sent to prison for three months.

xxxxxThen on the 22nd August 1819, a few days after the protest meeting, he launched a blistering attack upon the government’s handling of the affair. In a letter addressed to his constituents and subsequently published, he spoke of his shame, grief and indignation at the “blood spill at Manchester”. Was this then, he asked, why England, the land of freedom, had a standing army in peace time, to kill unarmed, unresisting men and women? This was nothing short of an “unparalleled and barbarous outrage”. But at the Leicester Assizes in March the following year, the judge saw the letter as calculated to do “infinite mischief”. He was found guilty of seditious libel, fined £2,000, and sent to prison for three months.

xxxxxThis was not the first time he had gone to prison for his beliefs, but it was to be his last. Whilst he continued his radical campaign, especially for religious freedom and electoral reform, his interest in reform began to wane. He doubtless viewed the passing of Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and the Reform Act of 1832 with a deal of satisfaction -

xxxxxIncidentally, as we shall see, an offshoot of the Peterloo Massacre was the Cato Street Conspiracy of 1820 (G4). The instigator of this plot, the militant radical Arthur Thistlewood, aimed to kill a number of Cabinet members to atone for the “souls of the murdered innocents” at Manchester.

xxxxxAmong those arrested and imprisoned was the main speaker at the demonstration, Henry “Orator” Hunt (1773-

xxxxxAmong those arrested and imprisoned was the main speaker at the demonstration, Henry “Orator” Hunt (1773-

xxxxxTrue to form, whilst at Ilchester, he spent some time writing about the poor conditions within the jail, and later published his comments in his A Peep into Prison. On release he continued his campaign for parliamentary reform, and in 1830 was elected a member of parliament for the working-

xxxxxAnd another man who was imprisoned for speaking his mind on the Peterloo Massacre was the English politician Sir Francis Burdett (1770-