xxxxxPeter the Great became sole ruler in 1689, determined to make Russia a great European power. He ratified the Treaty of Nerchinsk concerning the Russo-

PETER THE GREAT 1682 -

Acknowledgements

Peter the Great: detail, by the French painter Paul Hippolyte Delaroche (1797-

xxxxxPeter the Great (as he came to be known) became Tsar of Russia in 1682 and shared this title with his imbecilic half-

xxxxxPeter the Great (as he came to be known) became Tsar of Russia in 1682 and shared this title with his imbecilic half-

xxxxxAs the youngest son of Tsar Alexis by a second marriage, his childhood was spent in a village outside Moscow, not in the Kremlin itself. As a consequence, Peter's upbringing had been a comparatively liberal one, and he had mixed freely with European seamen, merchants and visitors. Such contacts convinced him that Russia's future lay in the West. He saw the need to reform his country on European lines, and increase its military and naval standing. It is little wonder that he is now regarded as the founder of the modern Russian state.

xxxxxHaving ratified the Treaty of Nerchinsk concerning the Russo-

xxxxxFollowing his initial success against the Turks, in March 1697, Peter turned his attention to Europe. Over the next eighteen months, accompanied by a large party of officials, he visited Prussia, Holland, England and Austria to study at first hand the latest methods of technical production, particularly artillery, fortification and shipbuilding. During his travels he recruited some 900 military experts, engineers and other artisans to assist him in his ambitious reforms. For a time, we are told, he even found employment for himself in the Dutch shipyard at Saardam, and the English naval dockyard at Deptford, working under an assumed name. On his return to Moscow he sent large numbers of young Russians to Europe to learn a variety of western skills and techniques.

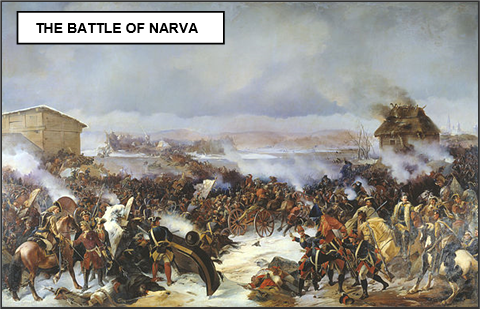

xxxxxIn 1700, with a confidence which proved badly misplaced, he agreed to join a European alliance against the Swedes who, under their king Charles XII, were bent on their own plans of conquest. For Russia, a victory over Sweden held out the possibility of gaining territory along the Baltic coast, thereby opening a "window on the west". But the first phase of the conflict which followed -

xxxxxIn 1700, with a confidence which proved badly misplaced, he agreed to join a European alliance against the Swedes who, under their king Charles XII, were bent on their own plans of conquest. For Russia, a victory over Sweden held out the possibility of gaining territory along the Baltic coast, thereby opening a "window on the west". But the first phase of the conflict which followed -

x xxxxIn the meantime, his reforms at home continued apace and, by the end of his reign, were to effect every aspect of national life. His nobles -

xxxxIn the meantime, his reforms at home continued apace and, by the end of his reign, were to effect every aspect of national life. His nobles -

xxxxxTo ensure vital military support for this dictatorship, Peter strengthened the aristocratic Guards Regiments, and developed them into privileged units loyal to the state. That such a force was required was clearly demonstrated in 1698 when the Streltsy (illustrated) once more entered politics and attempted to reinstate his half-

xxxxxTo ensure vital military support for this dictatorship, Peter strengthened the aristocratic Guards Regiments, and developed them into privileged units loyal to the state. That such a force was required was clearly demonstrated in 1698 when the Streltsy (illustrated) once more entered politics and attempted to reinstate his half-

xxxxxThe treatment meted out to the Streltsy bears testimony to Peter's capacity for cruelty. Together with his small band of drinking buddies (known collectively as "the Most Drunken Order of Fools and Jesters"), he took part and pleasure in the torture and the killing of the rebels. Later he was to be present at the torture of his own son. He was a big man -

xxxxxHowever, as we shall see, it proved but a temporary setback. By increasing his military and naval power he gained a resounding victory over the Swedes at the Battle of Poltava in 1709 (AN) and, with the building of St. Petersburg, acquired at last that vital "window on the west". It was on the strength of these achievements that Peter I came to be known as "Peter the Great" and was afforded the title Emperor of all the Russias.

xxxxxIncidentally, we are told that while working at Deptford he lived in an elegant house belonging to the diarist John Evelyn. By all accounts he left it in a disgusting state on his departure! ......

xxxxx...... His simplification of the Russian alphabet - s quite a major operation. In order to encompass new scientific, technical, cultural and political terms, he was obliged to produce a written language which not only combined existing versions within his own language, but also incorporated a large number of Western words and phrases.

s quite a major operation. In order to encompass new scientific, technical, cultural and political terms, he was obliged to produce a written language which not only combined existing versions within his own language, but also incorporated a large number of Western words and phrases.

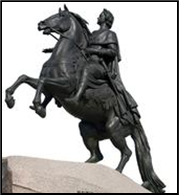

xxxxx…… A huge bronze equestrian monument to Peter the Great was unveiled in Saint Petersburg in 1782. The work of the French sculptor Étienne Maurice Falconet (1716-

W3-