xxxxxThe British politician Sir Robert Peel is remembered especially for establishing the world’s first organised police force, formed in London in 1829. Based at Scotland Yard, it proved highly successful, and similar forces were being set up across the country by 1856. It also acted as a model for police forces in other countries. In the same year he introduced the Catholic Emancipation Act, passed to stop the possibility of civil war in Ireland. Despite much opposition to this measure, he managed to remain in parliament and, as we shall see, two years after the Reform Act of 1832 (W4), his Tamworth Manifesto did much to launch the Conservative Party of the future. He later served as prime minister, but his controversial repeal of the Corn Laws in 1845 split the Tory Party and put an end to his career.

SIR ROBERT PEEL 1788 -

Acknowledgements

Peel: detail, by the English portrait painter John Linnell (1792-

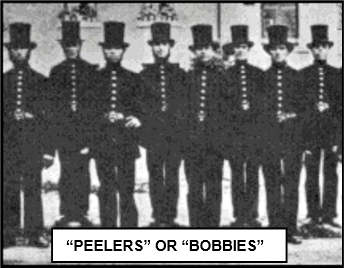

xxxxxThe English politician Sir Robert Peel served two terms as the British prime minister, passed the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, helped save his country from bankruptcy, and was responsible for the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, a decision which split the Tory Party and ended his political career. Today, however, he is mainly remembered for his act in 1829 when, as home secretary, he founded London’s Metropolitan Police Force. It was in his honour that the men of this force came to be known as “Peelers” or “Bobbies”. The first name has long since gone, but the second still remains, an affectionate term for the policeman on patrol, the “bobbie on his beat”.

xxxxxThe English politician Sir Robert Peel served two terms as the British prime minister, passed the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, helped save his country from bankruptcy, and was responsible for the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, a decision which split the Tory Party and ended his political career. Today, however, he is mainly remembered for his act in 1829 when, as home secretary, he founded London’s Metropolitan Police Force. It was in his honour that the men of this force came to be known as “Peelers” or “Bobbies”. The first name has long since gone, but the second still remains, an affectionate term for the policeman on patrol, the “bobbie on his beat”.

xxxxxAs we have seen, it was while serving as a chief magistrate at Bow Street, London, that the English novelist Henry Fielding recruited a small body of “thief takers”. They became known as the Bow Street Runners. Whilst they were generally successful, by the beginning of the 19th century the increase in lawlessness had led to a widespread demand for a more effective force to keep the peace, particularly in London. After much debate as to the form this body should take, Peel established the London Metropolitan Police Force in 1829, the world’s first police force drawn up on modern lines. It was well organised, highly disciplined, and its uniformed members carried no firearms. And along with the setting up of this centralised police force went a thorough reform of the prison system and penal code. This included a drastic reduction in the number of offences which carried the death penalty, numbering over 200 at that time and including crimes of an extremely petty nature.

xxxxxAfter a short period of concern and scepticism on the part of the general public, these law enforcers became recognised and respected by the citizens of London. Indeed, so successful did the force prove to be, that an Act of 1835 ordered all boroughs to set up similar police forces, and in 1856 provinces countrywide were told to do likewise. And by this date, or not long afterwards, other countries, including Australia, India and Canada, had established forces on the same model.

xxxxxThe headquarters of this new force was first established at No. 4 Whitehall Place, and this had a rear entrance onto Great Scotland Yard, an area so named because it was the site of a medieval palace where Scottish royalty used to stay when they visited London. It was from this association that the Criminal Investigation Department, the CID, acquired its name -

xxxxxPeel was born near Bury, Lancashire, the son of a wealthy cotton manufacturer. He was educated at Harrow School, and attended Oxford University before entering the House of Commons as a Tory in 1809, a seat bought for him by his father. An able administrator and fluent speaker, he gained his first major appointment, chief secretary for Ireland, in 1812. In this office, which he held for six years, he suppressed all signs of Irish agitation, showing no sympathy with the Roman Catholic demand for greater political freedom. Indeed, so strong was his opposition to such a move that it earned him the nickname “Orange Peel”, a reference to the Protestant Orange Order.

xxxxxAnd this opposition continued unabated when he was appointed home secretary in 1822. Indeed, when George Canning, a man in favour of Roman Catholic emancipation, became prime minister in 1827, Peel resigned in protest. However, on his return to office in 1828, following Canning’s sudden death, there was a rapid change of heart. In 1829, the same year as he established London’s police force, Peel introduced and carried through the Catholic Emancipation Act, virtually removing all limitations on the political and civil rights of Roman Catholics in the United Kingdom.

xxxxxAnd this opposition continued unabated when he was appointed home secretary in 1822. Indeed, when George Canning, a man in favour of Roman Catholic emancipation, became prime minister in 1827, Peel resigned in protest. However, on his return to office in 1828, following Canning’s sudden death, there was a rapid change of heart. In 1829, the same year as he established London’s police force, Peel introduced and carried through the Catholic Emancipation Act, virtually removing all limitations on the political and civil rights of Roman Catholics in the United Kingdom.

xxxxxThis volte-

xxxxxNot surprisingly this Act was strongly opposed by the King, the Anglican Church and a large number of Tories. Peel himself came under bitter attack and lost his seat at Oxford University, but he remained destined for high office. He returned to the Commons as a member for Tamworth in Staffordshire, and was to serve two terms as prime minister. As we shall see, his Tamworth Manifesto, set out two years after the Reform Act of 1832 (W4), did much to define the Conservative Party of the future, whilst his repeal of the Corn Laws during the Great Irish Famine of 1845 (Va), virtually put an end to the Tory Party of the past and his own political career.

xxxxxIncidentally, whilst living in Ireland Peel came across a breed of pig known as the “Irish Grazer”. Recognising their worth, he brought several back to his Drayton Manor Estate in Tamworth, Staffordshire, and started breeding them. Within a few years they became very popular as the Tamworth “Sandy Back” pig, and later in the century they were exported to countries throughout the English-

Including:

Daniel O’Connell

G4-

xxxxxThe Irish lawyer Daniel O’Connell (1775-

xxxxxThe Irish lawyer Daniel O’Connell led the fight to gain Roman Catholic Emancipation during the first three decades of the 19th century and, once achieved in 1829, took up the cause for Irish home rule. Born near Cahirciveen in County Kerry in 1775, he was educated in France but returned to study law, and was called to the bar in Dublin in 1798. A powerful orator and a commanding figure, he organised the Catholic Association in 1823 and, under his firm leadership, this highly popular movement played a significant role in convincing the British government that reform was necessary.

xxxxxThe Irish lawyer Daniel O’Connell led the fight to gain Roman Catholic Emancipation during the first three decades of the 19th century and, once achieved in 1829, took up the cause for Irish home rule. Born near Cahirciveen in County Kerry in 1775, he was educated in France but returned to study law, and was called to the bar in Dublin in 1798. A powerful orator and a commanding figure, he organised the Catholic Association in 1823 and, under his firm leadership, this highly popular movement played a significant role in convincing the British government that reform was necessary.

xxxxxBut the event which did more than anything to bring about political change occurred in 1828 when O’Connell stood as a candidate in a by-

xxxxx“The Liberator”, as O’Connell was dubbed, then took up the fight for Irish home rule. Demonstrations were organised, and it was after one of these, in 1843, that he was arrested and charged with seditious conspiracy. He was eventually acquitted and resumed the campaign, but by then some of his followers were advocating an armed struggle. He would have no part of that and, despite ill-

xxxxxAs we shall see, in 1845 (Va), two years before his death, the potato famine struck Ireland, leading to thousands of deaths and mass emigration. It was to ease this situation that Robert Peel repealed the Corn Laws in 1846 and again found himself at odds with his party.

xxxxxIncidentally, the main street in Dublin, previously known as Sackville Street, was renamed O’Connell Street in 1924. At the southern end of the street is O’Connell Bridge, built in 1880 and said to be wider than its length. Nearby is a statue of the man himself.