xxxxxIn 1884, as we have seen, the British determination to keep out of Sudanese affairs led to the First Anglo-Sudan War, a conflict which ended in the Siege of Khartoum and the death of General Charles Gordon. Sent to the Sudan to organise the evacuation of all the Egyptian garrisons, he and a defence force of some 7,000 men were slaughtered by the followers of the religious fanatic Muhammad Ahmed - the self-styled Mahdi - when the city was finally captured in January 1885.

xxxxxTowards the end of the century, however, the British were obliged to reconsider their commitment to the Sudan. Egypt, under their control since 1882, depended for its survival upon the head waters of the Nile, and these vital waters were becoming increasingly under threat, not by the Mahdist regime - still in power in the Sudan - but by other European nations bent on colonial expansion. The Belgians, the Italians and the French (befriended by the Russians) were all in a position to take advantage of Sudan’s instability, and if one of them did so, then the British occupation of Egypt - never liked by any of the European states - would be seriously threatened, economically as well as a politically. There were plans, for example, to build an irrigation dam at Aswan, and this meant that Britain had to control the higher reaches of the Nile.

xxxxxTowards the end of the century, however, the British were obliged to reconsider their commitment to the Sudan. Egypt, under their control since 1882, depended for its survival upon the head waters of the Nile, and these vital waters were becoming increasingly under threat, not by the Mahdist regime - still in power in the Sudan - but by other European nations bent on colonial expansion. The Belgians, the Italians and the French (befriended by the Russians) were all in a position to take advantage of Sudan’s instability, and if one of them did so, then the British occupation of Egypt - never liked by any of the European states - would be seriously threatened, economically as well as a politically. There were plans, for example, to build an irrigation dam at Aswan, and this meant that Britain had to control the higher reaches of the Nile.

xxxxxThis growing fear of colonial rivalry became a reality in 1896. By that year the Belgian and the Italians had been persuaded to keep out of the Nile Valley - by diplomatic means or veiled threats - but the French, supported by the Russians, were more serious in their intent. They already had a foothold in Somaliland in the east (the area around Djibouti) and, as we have seen, having gained the support of the Ethiopians by helping them to defeat the Italians at the Battle of Adowa in 1896, they saw Ethiopia as a staging ground for incursions into southern Sudan. This gave birth to a highly ambitious plan whereby a military expedition would march from the French Congo in West Africa to the town of Fashoda on the upper White Nile, and there build a dam to divert and thus reduce the flow of the Nile. This would link French possessions across Africa from west to east (from the Niger to the Nile); prevent the British from joining up their territories from north to south (Cairo to Cape Town) - the life-long dream, as we have seen, of the British diamond magnate Cecil Rhodes - and perhaps even force the British out of Egypt.

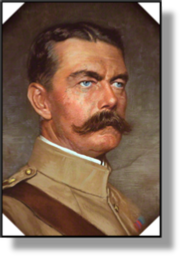

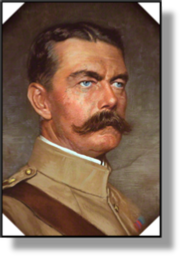

xxxxxThe French Nile expedition, led by Captain Jean-Baptiste Marchand, set out for Africa in June 1896, but long before then the British had come to the conclusion that, faced with this threat, the Sudan had to be re-conquered. Only by regaining command of its vast neighbour could Egypt - and, ipso facto, the British - safeguard the waters of the Nile. A string of reports coming out of the Sudan, all describing the brutality of the Mahdist regime, was sufficient to win over public support for this action, and early in 1896 the government ordered General Herbert Kitchener (illustrated) to lead an Anglo-Egyptian army into the Sudan. The Second Anglo-Sudan War was under way.

xxxxxThe French Nile expedition, led by Captain Jean-Baptiste Marchand, set out for Africa in June 1896, but long before then the British had come to the conclusion that, faced with this threat, the Sudan had to be re-conquered. Only by regaining command of its vast neighbour could Egypt - and, ipso facto, the British - safeguard the waters of the Nile. A string of reports coming out of the Sudan, all describing the brutality of the Mahdist regime, was sufficient to win over public support for this action, and early in 1896 the government ordered General Herbert Kitchener (illustrated) to lead an Anglo-Egyptian army into the Sudan. The Second Anglo-Sudan War was under way.

xxxxxThe Sudan at that time was under the rule of Khalifa Abdullah. He had succeeded Muhammad Ahmad, the self-styled Mahdi, when he died in June 1885, a few months after his successful siege of Khartoum. Abdullah had retained the general support of the majority of Sudanese tribes, but his attempts to spread Mahdism met with little success. In the west his hold on Darfur was weak, and in the east his successful attack upon the Ethiopians had gained little by way of territory. In the north his forces were roundly defeated at Tushki by an Anglo-Egyptian army led by General Francis Grenfell in 1889, and later an area in the upper Nile was infiltrated by troops from the Congo Free State of Leopold II of Belgium.

xxxxxThe Sudan at that time was under the rule of Khalifa Abdullah. He had succeeded Muhammad Ahmad, the self-styled Mahdi, when he died in June 1885, a few months after his successful siege of Khartoum. Abdullah had retained the general support of the majority of Sudanese tribes, but his attempts to spread Mahdism met with little success. In the west his hold on Darfur was weak, and in the east his successful attack upon the Ethiopians had gained little by way of territory. In the north his forces were roundly defeated at Tushki by an Anglo-Egyptian army led by General Francis Grenfell in 1889, and later an area in the upper Nile was infiltrated by troops from the Congo Free State of Leopold II of Belgium.

xxxxxGeneral Kitchener, who took over command of the Egyptian Army in 1892, had prepared well for the invasion. His force consisted of some 8,000 British and 17,000 Egyptian troops, all well trained and equipped, supported by artillery and a flotilla of river gunboats. He began moving his army slowly up the Nile in March 1896, laying a railway as he went to assist in the transport of reinforcements, and by the end of the month he had established his headquarters at Wadi Halfa, just inside the Sudan. Over the next six months he occupied the whole of Dongola province and met no serious resistance. Therexwere battles at Ferkeh and Hafir, but these were not sufficient to halt the advance. On advancing further south there were two notable engagements. In August 1897 the riverside town of Abu Hamed was captured by the invading force and this enabled the completion of the railway from Wadi Halfa to the Nile - vital for the supply of reinforcements. There then followed the Battle of Atbara River in which a force of some 18,000 Sudanese tribesmen was attacked and put to flight, suffering the loss of some 3,000 men.

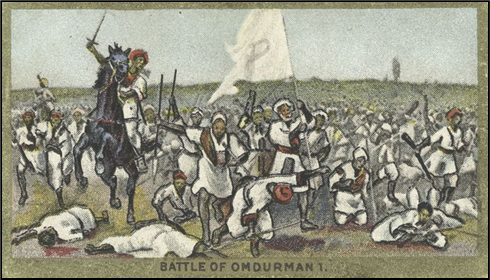

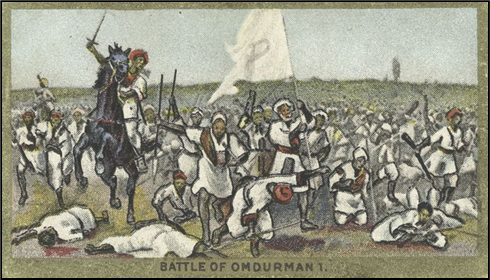

xxxxxFollowing this encounter, fought in April 1898, the Anglo-Egyptian army marched and sailed on towards what proved to be the decisive battle. By the end of August it had reached the plain in front of Omdurman, a town on the Nile, just north of Khartoum. Without delay and with little regard for the consequences, the Sudanese warriors - known in the West as “Dervishes” - then launched a frontal attack upon the invading force on the 2nd September (illustrated). As in earlier battles these tribesmen - armed with spears or outdated rifles - proved no match for the modern firepower of their enemy. Few if any got to within striking distance of their foe, blown up by the artillery or mown down by accurate fire from rifle or machine gun. Of the 50,000 taking part in the attack it is estimated that one fifth were killed. Anglo-Egyptian losses were put at 48 dead and fewer than 400 wounded.

xxxxxFollowing this encounter, fought in April 1898, the Anglo-Egyptian army marched and sailed on towards what proved to be the decisive battle. By the end of August it had reached the plain in front of Omdurman, a town on the Nile, just north of Khartoum. Without delay and with little regard for the consequences, the Sudanese warriors - known in the West as “Dervishes” - then launched a frontal attack upon the invading force on the 2nd September (illustrated). As in earlier battles these tribesmen - armed with spears or outdated rifles - proved no match for the modern firepower of their enemy. Few if any got to within striking distance of their foe, blown up by the artillery or mown down by accurate fire from rifle or machine gun. Of the 50,000 taking part in the attack it is estimated that one fifth were killed. Anglo-Egyptian losses were put at 48 dead and fewer than 400 wounded.

xxxxxBut the battle was far from over. When Kitchener then advanced his troops, anxious to capture Omdurman, the rearguard was suddenly attacked by a force of some 20,000 tribesmen which had been held in reserve, and there was fierce fighting before the attack was repulsed. Likewise the cavalry charge of the 21st lancers (illustrated), ordered to clear the way through the small number of Dervishes remaining on the battle field, suddenly found themselves confronted by a force of two to three thousand infantry which had been concealed in a hollow. They eventually managed to force the tribesmen to retreat, but not before losing seventy men and 120 horses. Andxbecause Khalifa Abdullah had escaped from the battlefield, the conquest of the Sudan was not completed until November 1899, when he was eventually confronted and killed at the Battle of Umm Diwaikarat.

xxxxxBut the battle was far from over. When Kitchener then advanced his troops, anxious to capture Omdurman, the rearguard was suddenly attacked by a force of some 20,000 tribesmen which had been held in reserve, and there was fierce fighting before the attack was repulsed. Likewise the cavalry charge of the 21st lancers (illustrated), ordered to clear the way through the small number of Dervishes remaining on the battle field, suddenly found themselves confronted by a force of two to three thousand infantry which had been concealed in a hollow. They eventually managed to force the tribesmen to retreat, but not before losing seventy men and 120 horses. Andxbecause Khalifa Abdullah had escaped from the battlefield, the conquest of the Sudan was not completed until November 1899, when he was eventually confronted and killed at the Battle of Umm Diwaikarat.

xxxxxBut Kitchener had no time to savour his victory at Omdurman. In July, while his army had been advancing up the Nile, the French expedition under the command of Captain Marchand had reached Fashoda on the Upper Nile and claimed the area as a French protectorate. Having achieved his mission - the re-conquest of the Sudan - Kitchener had now to ensure the very reason for the invasion, the safeguard of the waters of the Nile. With a sizeable force and a small flotilla, he pressed on up the Nile and met up with Captain Marchand on the 18th September. The French commander refused to withdraw and, as we shall see, there followed what came to be known as the Fashoda Incident of 1898, a confrontation between Britain and France which came close to an all-out war.

xxxxxIncidentally, the charge of the 21st Lancers at the Battle of Omdurman was the last charge made by a British cavalry regiment against a standing army. Winston Churchill, the British prime minister during the Second World War, 1940 to 1945, took part in the charge as a young subaltern and afterwards wrote about the campaign in The River War, An Account of the Re-conquest of the Sudan, published in 1899 (illustrated). As we shall see, he later served as a war correspondent in the Second Anglo-Boer War, beginning in 1899. ……

xxxxx…… As noted earlier, on the 4th September, two days after the Battle of Omdurman, a memorial service for Gordon was held in front of the palace where he was killed in January 1885.

xxxxxTowards the end of the century, however, the British were obliged to reconsider their commitment to the Sudan. Egypt, under their control since 1882, depended for its survival upon the head waters of the Nile, and these vital waters were becoming increasingly under threat, not by the Mahdist regime -

xxxxxTowards the end of the century, however, the British were obliged to reconsider their commitment to the Sudan. Egypt, under their control since 1882, depended for its survival upon the head waters of the Nile, and these vital waters were becoming increasingly under threat, not by the Mahdist regime - xxxxxThe French Nile expedition, led by Captain Jean-

xxxxxThe French Nile expedition, led by Captain Jean- xxxxxThe Sudan at that time was under the rule of Khalifa Abdullah. He had succeeded Muhammad Ahmad, the self-

xxxxxThe Sudan at that time was under the rule of Khalifa Abdullah. He had succeeded Muhammad Ahmad, the self- xxxxxFollowing this encounter, fought in April 1898, the Anglo-

xxxxxFollowing this encounter, fought in April 1898, the Anglo- xxxxxBut the battle was far from over. When Kitchener then advanced his troops, anxious to capture Omdurman, the rearguard was suddenly attacked by a force of some 20,000 tribesmen which had been held in reserve, and there was fierce fighting before the attack was repulsed. Likewise the cavalry charge of the 21st lancers (illustrated), ordered to clear the way through the small number of Dervishes remaining on the battle field, suddenly found themselves confronted by a force of two to three thousand infantry which had been concealed in a hollow. They eventually managed to force the tribesmen to retreat, but not before losing seventy men and 120 horses. Andxbecause Khalifa Abdullah had escaped from the battlefield, the conquest of the Sudan was not completed until November 1899, when he was eventually confronted and killed at the Battle of Umm Diwaikarat.

xxxxxBut the battle was far from over. When Kitchener then advanced his troops, anxious to capture Omdurman, the rearguard was suddenly attacked by a force of some 20,000 tribesmen which had been held in reserve, and there was fierce fighting before the attack was repulsed. Likewise the cavalry charge of the 21st lancers (illustrated), ordered to clear the way through the small number of Dervishes remaining on the battle field, suddenly found themselves confronted by a force of two to three thousand infantry which had been concealed in a hollow. They eventually managed to force the tribesmen to retreat, but not before losing seventy men and 120 horses. Andxbecause Khalifa Abdullah had escaped from the battlefield, the conquest of the Sudan was not completed until November 1899, when he was eventually confronted and killed at the Battle of Umm Diwaikarat.