xxxxxAusten Layard (1817-

xxxxxAusten Layard (1817-

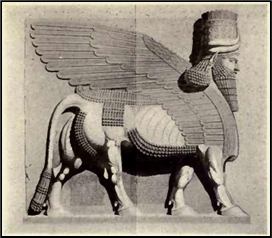

xxxxxKnowing that Nineveh had been sited on the River Tigris, near the city of Mosul (in today’s Iraq), he began excavating at a likely site in 1845. Over the next five years he discovered the remains of some magnificent palaces and collected pieces of art work from the 9th to the 7th century BC, but, as the work progressed, he began to realise that he had not found Nineveh, but had unearthed the ruins of the ancient city of Calah (modern Nimrud). Many of his most significant findings dated from the reign of Aschurnasirpal II, the Assyrian king who rebuilt the city around 880 BC, and made it his capital. Among these finds were a huge winged bull -

xxxxxIn 1849, much encouraged and not a little surprised by his success at Nimrud, Layard again attempted to find the remains of Nineveh. He began digging at Kuyunjik, a site on the east bank of the Tigris, opposite Mosul, and this time he succeeded in uncovering the famous city of antiquity, capital of the Assyrian empire from the 8th century BC until its destruction by the Medes in 612 BC. Foremost amongst his discoveries was the magnificent “palace without a rival” of Sennacherib, the king who, around 700 BC, had made Nineveh one of the most beautiful and advanced cities in the Middle East. From here he recovered two miles of wall paintings and, once again, thousands of cuneiform tablets -

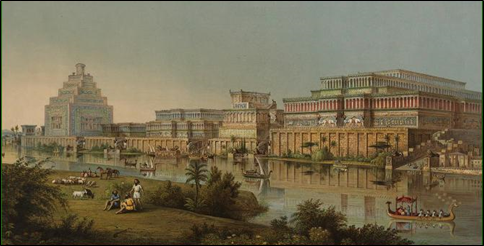

xxxxxIn 1849, much encouraged and not a little surprised by his success at Nimrud, Layard again attempted to find the remains of Nineveh. He began digging at Kuyunjik, a site on the east bank of the Tigris, opposite Mosul, and this time he succeeded in uncovering the famous city of antiquity, capital of the Assyrian empire from the 8th century BC until its destruction by the Medes in 612 BC. Foremost amongst his discoveries was the magnificent “palace without a rival” of Sennacherib, the king who, around 700 BC, had made Nineveh one of the most beautiful and advanced cities in the Middle East. From here he recovered two miles of wall paintings and, once again, thousands of cuneiform tablets - were valued highly, and came to make up the major part of the British Museum’s Assyrian collection. Furthermore, Layard’s books about his excavations proved extremely popular, especially his Nineveh and Its Remains, published in 1849 (and relating in fact to his excavations at Calah!), and his authentic Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh an Babylon, in 1853. The impression of Nineveh illustrated here was by the Scottish architectural historian James Ferguson (1808-

were valued highly, and came to make up the major part of the British Museum’s Assyrian collection. Furthermore, Layard’s books about his excavations proved extremely popular, especially his Nineveh and Its Remains, published in 1849 (and relating in fact to his excavations at Calah!), and his authentic Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh an Babylon, in 1853. The impression of Nineveh illustrated here was by the Scottish architectural historian James Ferguson (1808-

xxxxxLayard went on to make soundings at other sites in Mesopotamia, including Babylon, thereby adding greatly to the knowledge of the area, and on his return to England entered politics. He was a Member of Parliament during the 1850s and 1860s, held a number of government appointments, and ended his career as the British ambassador in Istanbul. He was knighted in 1878, retired two years later, and went to live in Venice in 1884.

xxxxxThe area around Mosul and Babylon further south had been surveyed much earlier in the century, but the first archaeological excavation in Mesopotamia was carried out in 1843 by the French consul at Mosul, Émile Botta (1802-

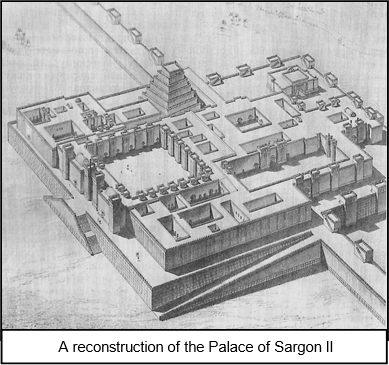

xxxxxThe area around Mosul and Babylon further south had been surveyed much earlier in the century, but the first archaeological excavation in Mesopotamia was carried out in 1843 by the French consul at Mosul, Émile Botta (1802- however, attracted by what he thought was a more likely location, he moved further north to Khorsabad and began digging there. Within a matter of days he had unearthed the ancient city of Dur Sharrukin, and discovered the remains of the great palace of Sargon II, together with a large number of relief sculptures and cuneiform tablets. Still believing that he had found the vanished city of Nineveh, he informed the French government of his find, and they actually sent out an artist to make drawings of the remains. Many of these were included in Botta’s publication of 1850, mistakenly entitled Monuments of Nineveh. Botta stayed on in the Middle East, serving as consul in Jerusalem and then Tripoli.

however, attracted by what he thought was a more likely location, he moved further north to Khorsabad and began digging there. Within a matter of days he had unearthed the ancient city of Dur Sharrukin, and discovered the remains of the great palace of Sargon II, together with a large number of relief sculptures and cuneiform tablets. Still believing that he had found the vanished city of Nineveh, he informed the French government of his find, and they actually sent out an artist to make drawings of the remains. Many of these were included in Botta’s publication of 1850, mistakenly entitled Monuments of Nineveh. Botta stayed on in the Middle East, serving as consul in Jerusalem and then Tripoli.

xxxxxIncidentally, it was during further excavations in Mesopotamia that the Sumerians, a previously unknown people, were discovered. They had lived in the country before the coming of the Babylonians and Assyrians. It was the English archaeologist Leonard Woolley who discovered their Royal Tombs during his uncovering of the ancient Sumerian city of Ur in 1927.

xxxxxIn 1839 the Englishman Austen Layard (1817-

AUSTEN LAYARD DISCOVERS NINEVEH

1849 (Va)

Acknowledgements

Layard: portrait in chalk by the English artist George Frederic Watts (1817-

Including:

Emile Botta, Henry

Creswicke Rawlinson

and Charles Newton

Va-

xxxxxThe Englishman Henry Creswicke Rawlinson (1810-

xxxxxThe discovery of thousands of clay tablets and stone carvings inscribed with written texts, unearthed around Mosul and then in Babylonia further south, proved one of the most important finds. A number of scholars then set to work to decipher the cuneiform script and bring to light the history of these ancient kingdoms. The first man to do so was the English orientalist Henry Creswicke Rawlinson (1810-

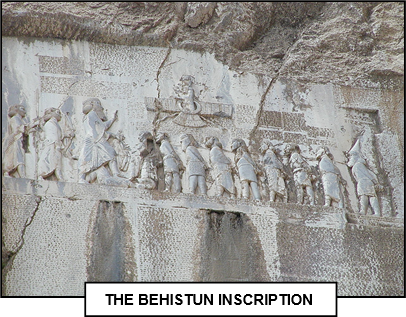

xxxxxThe discovery of thousands of clay tablets and stone carvings inscribed with written texts, unearthed around Mosul and then in Babylonia further south, proved one of the most important finds. A number of scholars then set to work to decipher the cuneiform script and bring to light the history of these ancient kingdoms. The first man to do so was the English orientalist Henry Creswicke Rawlinson (1810- and, written in three languages, had been carved on a rock face in the village of Behistun.

and, written in three languages, had been carved on a rock face in the village of Behistun.

xxxxxHe published his results in his Persian Cuneiform Inscription at Behistun, and this enabled the other two languages, the Babylonian and Elamite versions, to be translated comparatively quickly. By 1857 the Mesopotamian cuneiform script had been mastered and, by reading the clay tablets and stone carvings found during excavations, a history of ancient Babylonia and Assyria could be compiled, and a much greater knowledge gained of biblical history.

xxxxxRawlinson became consul general at Baghdad in 1851, and it was in this post that he was able to continue Layard’s work by collecting and sending ancient artwork to the British Museum. He was knighted in 1855, and was a member of parliament for a few years before being appointed minister to the Iranian court in 1859. Among his other works was an Outline of the History of Assyria published in 1852.

xxxxxIncidentally, the German scholar George Grotefend (1775-

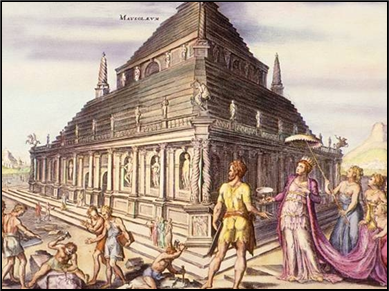

xxxxxAndxit was during this period, in 1856, that the English archaeologist Charles Newton (1816-

xxxxxAndxit was during this period, in 1856, that the English archaeologist Charles Newton (1816-

xxxxxNewton sent many fragments of the tomb’s sculptures and frieze, together with a ten foot statue (probably of Mausolus himself) back to the British Museum. Later, as curator of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the museum, he added substantially to the museum’s collections, and did much to promote an interest in Greek art. He was knighted in 1887.

xxxxxAxfew years earlier and much further afield, the American traveller John Lloyd Stephens (1805-

xxxxxAxfew years earlier and much further afield, the American traveller John Lloyd Stephens (1805-

xxxxxThe quest to discover the remains of past civilisations, particularly in the Middle East, gained momentum with the years. As we shall see, the German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann discovered the ancient city of Troy in Asia Minor in 1873 (Vb), the English archaeologist Flinders Petrie revealed precious remains of ancient Egypt in 1884 (Vc), and in 1900 (Vc) the Englishman Arthur Evans, beginning work at Knossos, on the island of Crete, unearthed a bronze age civilisation.