xxxxxThe London-born John Nash, the leading architect of his day, designed in a variety of styles, his buildings ranging from Gothic “castles”, classical mansions, townhouses, and exotic extravaganzas like the Royal Pavilion in Brighton. But, as a close friend of the Prince Regent, he is mostly remembered today for his Regency Style, a restrained classical architecture which transformed many parts of London. His major accomplishment was the design of Regent’s Park and its surrounding area, begun in 1811, and including Regent Street and the building of splendid terraces of elegant town houses. The cost of these schemes alarmed the government, however, and his rebuilding of Buckingham Palace, started in 1825, was severely criticised for the expense incurred, and the poor quality of some of its construction. When the Prince Regent died in 1830, Nash was dismissed, and spent the last years of his life in retirement at his home at Cowes on the Isle of Wight. Early on in his career he worked with the landscape gardener Humphry Repton.

JOHN NASH 1752 - 1835 (G2, G3a, G3b, G3c, G4, W4)

Acknowledgements

Nash: date and artist unknown. Cumberland Terrace: by the English artist Thomas Hosmer Shepherd (1792-1864), 1827/8. Royal Pavilion: by the English engraver George Baxter (1804-1867), 1827. Buckingham Palace: by the Anglo German lithographer Rudolf Ackermann (1764-1834), contained in The Microcosm of London, a three-volume work published by Ackermann 1808-1811. Marble Arch: wood engraving of 1851, artist unknown. Repton: miniature, watercolour on ivory, by the British artist John Downman (1750-1824), c1790. Stoneleigh Abbey: watercolour by Repton himself, 1808. London Bridge: by the English artist William Darton (active 1880-1940). Rennie: by the Scottish portrait painter Henry Raeburn (1756-1823), 1810 – Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh. Bell Rock: 1824, by the Scottish engraver John Horsburgh (1791-1869), after a drawing by the English artist J.M.W. Turner – Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington.

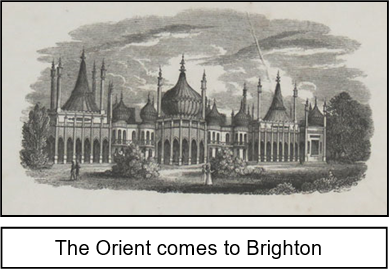

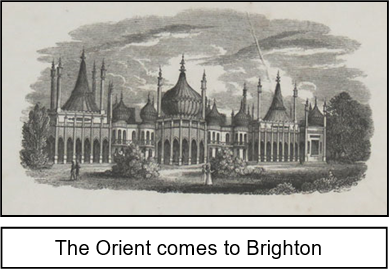

xxxxx After a shaky start, the London-born architect John Nash became the leading English architect of his day. A man of rare talent, he designed in a variety of styles, his buildings ranging from Gothic country “castles”, elegant classical mansions, semi-detached townhouses and pseudo Italian villas - not to mention the exuberant oriental extravaganza he made of the Royal Pavilion in Brighton.

After a shaky start, the London-born architect John Nash became the leading English architect of his day. A man of rare talent, he designed in a variety of styles, his buildings ranging from Gothic country “castles”, elegant classical mansions, semi-detached townhouses and pseudo Italian villas - not to mention the exuberant oriental extravaganza he made of the Royal Pavilion in Brighton.

xxxxxToday, however, he is chiefly remembered as the city planner who carried neo-classicism into the 19th century, and became London’s chief exponent of the Regency Style. This was characterised by a restrained imitation of ancient classical architecture - often Greek inspired - and so named because it was the dominant style during the Regency of George, Prince of Wales (1811 to 1820). In this particular mode he was responsible for a large number of memorable London buildings and designs, including work on Buckingham Palace and the development of Regent’s Park and its surrounding area, an overall scheme officially known as “The Metropolitan Improvements”.

xxxxxAfter completing his training, Nash worked in London, but struggled to survive. He eventually went bankrupt, and in 1783 moved to Wales to find work. Here he made a name for himself designing picturesque country houses and cottages in collaboration with the landscape gardener Humphry Repton. Such was his success that he returned to London in 1796 and, over the next fifteen years, took to designing a variety of Gothic-styled country houses in the shape of medieval castles. One of the first was his own palatial home, East Cowes Castle on the Isle of Wight, and then, among others, came Luscombe in South Devon, Knepp Castle in Sussex, Ravensworth in County Durham, and Caerhayes in Cornwall. His Cronkhill in Shropshire, built around 1802 in the style of an Italian villa, started a vogue which stretched into the Victorian era.

xxxxxNot surprisingly, his work came to the attention of the Prince Regent, and in 1811 he was commissioned to develop Marylebone Park, a large area of farmland in north London which had recently reverted to crown ownership. It was here that Nash developed his master plan for Regent’s Park and its environs. Named after his patron, it was an ambitious piece of city planning, comprising the Regent’s Canal, a lake, a stretch of woodland, and, at its landscaped edges, elegant shopping arcades and groups of grandiose houses, varying in size and forming attractive crescents and terraces. Most of the brick houses were given stucco facades, a covering of durable plaster which, suitably marked and coloured, gave the illusion that the dwellings were made of stone. And within this gigantic scheme was the creation of Regent Street - a sweeping thoroughfare originally planned to link Regent’s Park to Whitehall (never fully completed), plus the idea of Trafalgar Square and the re-designing of St. James’ Park. Later came the building of Carlton House, Cumberland Terrace (illustrated) and Clarence House, the future home of William IV. The park itself was intended as an area of leisure for members of the royal family, but it was opened to the public in 1838.

xxxxxNot surprisingly, his work came to the attention of the Prince Regent, and in 1811 he was commissioned to develop Marylebone Park, a large area of farmland in north London which had recently reverted to crown ownership. It was here that Nash developed his master plan for Regent’s Park and its environs. Named after his patron, it was an ambitious piece of city planning, comprising the Regent’s Canal, a lake, a stretch of woodland, and, at its landscaped edges, elegant shopping arcades and groups of grandiose houses, varying in size and forming attractive crescents and terraces. Most of the brick houses were given stucco facades, a covering of durable plaster which, suitably marked and coloured, gave the illusion that the dwellings were made of stone. And within this gigantic scheme was the creation of Regent Street - a sweeping thoroughfare originally planned to link Regent’s Park to Whitehall (never fully completed), plus the idea of Trafalgar Square and the re-designing of St. James’ Park. Later came the building of Carlton House, Cumberland Terrace (illustrated) and Clarence House, the future home of William IV. The park itself was intended as an area of leisure for members of the royal family, but it was opened to the public in 1838.

xxxxxIn 1813 Nash was appointed deputy surveyor general, a post he held for two years. It was during this period that, working closely with the Prince Regent, he started rebuilding the Royal Pavilion which overlooked the seafront at Brighton in Sussex. On the whim of the Regent, he transformed what was a simple classical villa into a fanciful oriental palace, topped with exotic onion-shaped domes and minaret-shaped chimneys, and decorated and furnished in a wildly exuberant mixture of Chinese and Mughal Indian styles. It was very imaginative, highly original, and enormously expensive.

xxxxxIn 1813 Nash was appointed deputy surveyor general, a post he held for two years. It was during this period that, working closely with the Prince Regent, he started rebuilding the Royal Pavilion which overlooked the seafront at Brighton in Sussex. On the whim of the Regent, he transformed what was a simple classical villa into a fanciful oriental palace, topped with exotic onion-shaped domes and minaret-shaped chimneys, and decorated and furnished in a wildly exuberant mixture of Chinese and Mughal Indian styles. It was very imaginative, highly original, and enormously expensive.

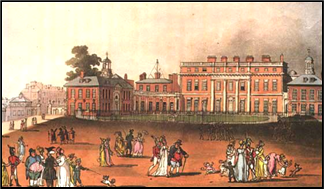

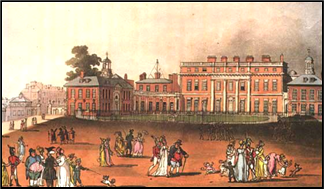

xxxxxAnd also proving excessively expensive was his next project, the repair and enlargement of what now came to be known as Buckingham Palace. This was originally a house constructed in the reign of James I, and it acquired its name when it was rebuilt by the Duke of Buckingham at the beginning of the 18th century. George III bought Buckingham House in 1761, but it was left to his son, the extravagant Prince Regent, to embark on a royal face-lift. In 1825 Nash began adding a suite of rooms on the garden side, but struggled to put his outline plans into effect. At one stage he was obliged pull down part of his development and start again. In the meantime the cost of the scheme had rocketed to well over double the estimated cost. When George IV died in 1830, Nash was dismissed from the project, and faced severe criticism the following year when an official inquiry was held concerning the cost of the project and the quality of the workmanship.

xxxxxAnd also proving excessively expensive was his next project, the repair and enlargement of what now came to be known as Buckingham Palace. This was originally a house constructed in the reign of James I, and it acquired its name when it was rebuilt by the Duke of Buckingham at the beginning of the 18th century. George III bought Buckingham House in 1761, but it was left to his son, the extravagant Prince Regent, to embark on a royal face-lift. In 1825 Nash began adding a suite of rooms on the garden side, but struggled to put his outline plans into effect. At one stage he was obliged pull down part of his development and start again. In the meantime the cost of the scheme had rocketed to well over double the estimated cost. When George IV died in 1830, Nash was dismissed from the project, and faced severe criticism the following year when an official inquiry was held concerning the cost of the project and the quality of the workmanship.

xxxxxAs an architect, Nash was a man of vision, and showed extraordinary talent in the art of town planning. It must be said, however, that during his career questions were raised at times about his building standards, and eyebrows were likewise raised - including those of the prime minister, the Duke of Wellington - concerning the inordinate cost of some of his projects. As a pleasant, easy-going man, he was not averse to cutting corners in his work, and he was no business man. Thus despite his achievement in creating much of Regency London, no honours came his way, and that was a sad ending for a man of such ability. He spent the last years of his life quietly at his home at Cowes on the Isle of Wight, and was buried at St. James’ Church in the town.

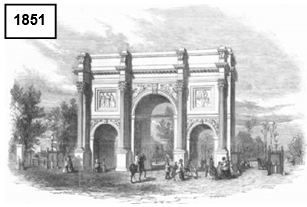

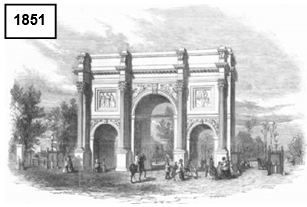

xxxxxIncidentally, when working on Buckingham Palace in 1828 Nash designed a triumphal arch to commemorate the victories of Trafalgar and Waterloo, and to serve as an imposing ceremonial entrance to the palace - based on the Constantine Arch in Rome. In keeping with the string of misfortunes which beset him at this time, it proved to be too narrow for the royal state coach, and in 1851 was moved to Hyde Park Corner at the western end of Oxford Street - the former site of Tyburn Gallows and the present day site of Speaker’s Corner for soapbox orators. It was called Marble Arch because it was made of Carrara marble. The palace itself did not become a royal residence until Queen Victoria came to the throne in 1837. William IV did not like the place, and refused to live there. Wings were added later in the century, and in 1913 the frontage was refaced. ……

xxxxxIncidentally, when working on Buckingham Palace in 1828 Nash designed a triumphal arch to commemorate the victories of Trafalgar and Waterloo, and to serve as an imposing ceremonial entrance to the palace - based on the Constantine Arch in Rome. In keeping with the string of misfortunes which beset him at this time, it proved to be too narrow for the royal state coach, and in 1851 was moved to Hyde Park Corner at the western end of Oxford Street - the former site of Tyburn Gallows and the present day site of Speaker’s Corner for soapbox orators. It was called Marble Arch because it was made of Carrara marble. The palace itself did not become a royal residence until Queen Victoria came to the throne in 1837. William IV did not like the place, and refused to live there. Wings were added later in the century, and in 1913 the frontage was refaced. ……

xxxxx…… The bizarre mixture of Indian and Chinese styles which makes up the Royal Pavilion at Brighton did not please Queen Victoria when she came to the throne in 1837. She had all the furniture removed and planned to have it demolished. The people of Brighton saved it by buying it from the Queen, and she used the money to give Buckingham Palace yet another face-lift.

Including:

Humphry Repton

and John Rennie

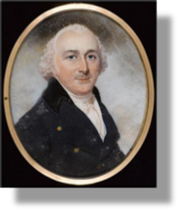

xxxxxHumphry Repton (1752-1818), who collaborated with John Nash in the 1790s, succeeded Capability Brown as the most distinguished landscape gardener of the day. He was in basic agreement with Brown’s ideas, but influenced in part by the current “Picturesque Movement” - which favoured wild landscapes - he incorporated a greater number and variety of plants in his designs. And he further modified Brown’s layout by tending to provide formal flower beds in open terraces which extended from the house and overlooked the natural, unkempt beauty of the parkland beyond. He began his business in 1788 and, as an amateur watercolour artist, drummed up a lot of custom by being able to provide his potential clients with a quick coloured sketch of his proposed plans.

xxxxxHumphry Repton (1752-1818), who collaborated with John Nash in the 1790s, succeeded Capability Brown as the most distinguished landscape gardener of the day. He was in basic agreement with Brown’s ideas, but influenced in part by the current “Picturesque Movement” - which favoured wild landscapes - he incorporated a greater number and variety of plants in his designs. And he further modified Brown’s layout by tending to provide formal flower beds in open terraces which extended from the house and overlooked the natural, unkempt beauty of the parkland beyond. He began his business in 1788 and, as an amateur watercolour artist, drummed up a lot of custom by being able to provide his potential clients with a quick coloured sketch of his proposed plans.

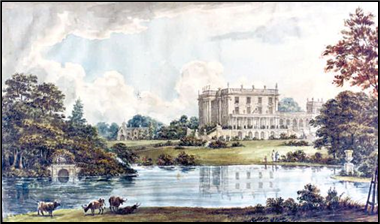

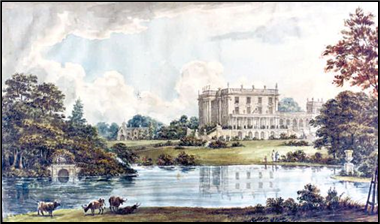

xxxxxHe worked successfully with Nash in providing garden schemes for a number of houses and cottages in Wales, but later, following his return to London, he quarrelled with him, claiming that the Mughal style of architecture that Nash used in the rebuilding of the Royal Pavilion at Brighton had been stolen from a design he himself had put forward. Later he chose to go into business with his son, John Addey Repton, a trained architect. During his career he published his ideas in a number of books, his major works being Sketches and Hints on Landscape Gardening in 1794, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening in 1803, and An Inquiry into the Changes of Taste in Landscape Gardening, three years later. He is credited with having invented the term “landscape gardening”. Illustrated here is his proposed garden scheme for Stoneleigh Abbey, Warwickshire.

xxxxxHe worked successfully with Nash in providing garden schemes for a number of houses and cottages in Wales, but later, following his return to London, he quarrelled with him, claiming that the Mughal style of architecture that Nash used in the rebuilding of the Royal Pavilion at Brighton had been stolen from a design he himself had put forward. Later he chose to go into business with his son, John Addey Repton, a trained architect. During his career he published his ideas in a number of books, his major works being Sketches and Hints on Landscape Gardening in 1794, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening in 1803, and An Inquiry into the Changes of Taste in Landscape Gardening, three years later. He is credited with having invented the term “landscape gardening”. Illustrated here is his proposed garden scheme for Stoneleigh Abbey, Warwickshire.

xxxxxIncidentally, it was the theorist Sir Uvedale Price (1747-1829), a friend of Repton and one of Nash’s patrons, who advocated the picturesque style in its purest form. A man caught up in the Romantic Movement, in his Essay on the Picturesque of 1794 he argued that parkland should be kept wild, dramatic and unkempt - as to be seen in the paintings by the French artist Claude Lorrain - in order to provide a romantic setting for pseudo-Gothic architecture and the like. He therefore advocated a formal garden immediately around the house, a landscape style garden beyond, and then parkland left in its natural state. In this style he was supported by the English writer and artist William Gilpin (1724-1804). In 1768 he advocated a texture that was rough, varied, and devoid of “obvious straight lines”.

xxxxxHumphry Repton (1752-1818), who worked with Nash in the 1790s, succeeded Capability Brown as the leading landscape gardener of the day. His ideas were similar to those of Brown, but his parkland was more naturally wild, and he tended to favour a more formal design around the house, based on open terraces. He started his business in 1788, and collaborated well with Nash in providing landscape schemes for houses and cottages in Wales. However, on returning to London they quarrelled over plans for the Royal Pavilion at Brighton, Repton claiming that his Mughal designs for the building had been stolen and used by Nash. From then on he worked with his architect son. He wrote a number of books, and these included Sketches and Hints on Landscape Gardening, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, and a An Inquiry into the Changes of Taste in Landscape Gardening.

G3c-1802-1820-G3c-1802-1820-G3c-1802-1820-G3c-1802-1820-G3c-1802-1820-G3c

xxxxxThe Scottish engineer John Rennie (1761-1821), like his contemporary John Nash, changed London’s appearance quite considerably. He designed three bridges over the Thames: Waterloo Bridge, completed in 1817, Southwick Bridge, finished two years later, and the new London Bridge, built after his death by his son, John Rennie, and opened in 1831. He began his career as a millwright, working for his fellow countryman James Watt, but started his own business in 1791 and over the next thirty years built or improved docks, canals, harbours and bridges throughout Britain. In addition to his London bridges, his major works included the Kennet and Avon Canal, the London and East India docks, and improvements to the naval dockyards at Plymouth, Portsmouth and Chatham, and to the harbours at Holyhead and Hull.

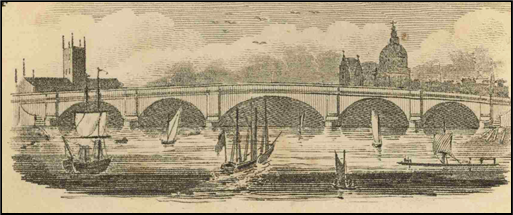

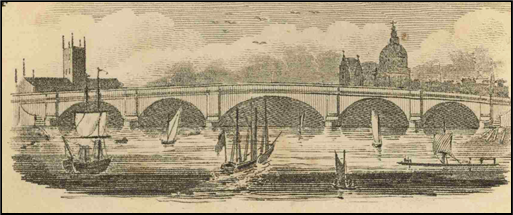

xxxxxLike his contemporary John Nash, the Scottish civil engineer John Rennie (1761-1821) also made important changes to London’s appearance. He was responsible for the building of three bridges over the Thames: - Waterloo Bridge, made up of three masonry arches and completed in 1817; Southwick Bridge, constructed of three cast-iron arches and finished just two years later; and the new London Bridge (illustrated), a structure he designed but did not live to see built. His architect son, also John Rennie, supervised its five-arch construction, and it was completed in 1831. Waterloo Bridge, the first to be so named, was seen by the Italian sculptor Antonio Canova when he visited London to inspect the Elgin Marbles. He described it as “the noblest bridge in the world”.

xxxxxLike his contemporary John Nash, the Scottish civil engineer John Rennie (1761-1821) also made important changes to London’s appearance. He was responsible for the building of three bridges over the Thames: - Waterloo Bridge, made up of three masonry arches and completed in 1817; Southwick Bridge, constructed of three cast-iron arches and finished just two years later; and the new London Bridge (illustrated), a structure he designed but did not live to see built. His architect son, also John Rennie, supervised its five-arch construction, and it was completed in 1831. Waterloo Bridge, the first to be so named, was seen by the Italian sculptor Antonio Canova when he visited London to inspect the Elgin Marbles. He described it as “the noblest bridge in the world”.

xxxxxRennie was born at Phantassie, near Haddington, East Lothian, and studied at Edinburgh University. He began his career as a millwright, and as from 1784 worked for the Scottish engineer James Watt for a number of years. During this time he much improved the machinery at the Boulton and Watt Albion mills in London, replacing wooden parts for those made of iron. He set up his own business in 1791, and it was from then that he became involved in building or improving docks, canals, harbours and bridges throughout Britain. This work, in which he pioneered the use of new materials and undertook vast and demanding projects, marked him out as one of the greatest civil engineers of his day.

xxxxxRennie was born at Phantassie, near Haddington, East Lothian, and studied at Edinburgh University. He began his career as a millwright, and as from 1784 worked for the Scottish engineer James Watt for a number of years. During this time he much improved the machinery at the Boulton and Watt Albion mills in London, replacing wooden parts for those made of iron. He set up his own business in 1791, and it was from then that he became involved in building or improving docks, canals, harbours and bridges throughout Britain. This work, in which he pioneered the use of new materials and undertook vast and demanding projects, marked him out as one of the greatest civil engineers of his day.

xxxxxIn addition to his London bridges, his major works included the semi-elliptical-arch bridge over the Tweed River at Kelso, Scotland, completed in 1803, the Kennet and Avon Canal - a 90 mile stretch linking the Thames with the Avon at Bath, opened in 1810 -, the London and East India docks on the River Thames, and substantial improvements to the naval dockyards at Plymouth, Portsmouth and Chatham, and to the harbours at Wick, Holyhead, Grimsby and Hull. He was also involved in a large drainage project in the Lincolnshire fens, and he began the building of the breakwater at Plymouth Sound - completed by his son John.

xxxxxIncidentally, Rennie’s Waterloo Bridge was demolished in 1936, and replaced in 1945. His New London Bridge, which, took the place of the old London Bridge (begun in 1176), was completed in 1831, but this five-arched masonry structure was dismantled in 1968 and, having been bought by a U.S. oil company, was reassembled at Lake Havasu City, Arizona, as a tourist attraction. The present bridge, completed in 1972, is made of pre-stressed concrete, and can take six lines of traffic! ……

xxxxx…… Inx1807 Rennie collaborated with his fellow countryman and engineer Robert Stevenson (1772-1850) in the building of the famous Bell Rock Lighthouse, situated off the east coast of Scotland, about twelve miles southeast of Arbroath. It took five years to complete, and later, in 1824, Stevenson published his Account of the Bell Rock Lighthouse. Stevenson, who designed and built lighthouses, had three sons, and they assisted him in his work. The youngest, Thomas, was the father of the famous writer Robert Louis Stevenson, author of Treasure Island. The rock on which the lighthouse was built - so called because it had a bell which, struck by the waves, sounded out a warning - is also called Inchcape Rock. The English poet Robert Southey wove a story around the rock and its bell in his ballad The Inchcape Rock. ……

xxxxx…… Inx1807 Rennie collaborated with his fellow countryman and engineer Robert Stevenson (1772-1850) in the building of the famous Bell Rock Lighthouse, situated off the east coast of Scotland, about twelve miles southeast of Arbroath. It took five years to complete, and later, in 1824, Stevenson published his Account of the Bell Rock Lighthouse. Stevenson, who designed and built lighthouses, had three sons, and they assisted him in his work. The youngest, Thomas, was the father of the famous writer Robert Louis Stevenson, author of Treasure Island. The rock on which the lighthouse was built - so called because it had a bell which, struck by the waves, sounded out a warning - is also called Inchcape Rock. The English poet Robert Southey wove a story around the rock and its bell in his ballad The Inchcape Rock. ……

xxxxx…… There was certainly a need for a lighthouse at this point. During a storm in 1779, no less than 70 ships were wrecked on the reef. ……

xxxxx…… When the novelist and poet Sir Walter Scott visited the lighthouse in 1815 he wrote the following in the log:

PHIAROS LOQUITUR

'Far on the bosom of the deep,

O'er these wild shelves my watch I keep;

A ruddy gem of changeful light,

Bound on the dusky brow of Night;

The seaman bids my lustre hail,

And scorns to strike his tim'rous sail'

After a shaky start, the London-

After a shaky start, the London- xxxxxNot surprisingly, his work came to the attention of the Prince Regent, and in 1811 he was commissioned to develop Marylebone Park, a large area of farmland in north London which had recently reverted to crown ownership. It was here that Nash developed his master plan for Regent’s Park and its environs. Named after his patron, it was an ambitious piece of city planning, comprising the Regent’s Canal, a lake, a stretch of woodland, and, at its landscaped edges, elegant shopping arcades and groups of grandiose houses, varying in size and forming attractive crescents and terraces. Most of the brick houses were given stucco facades, a covering of durable plaster which, suitably marked and coloured, gave the illusion that the dwellings were made of stone. And within this gigantic scheme was the creation of Regent Street -

xxxxxNot surprisingly, his work came to the attention of the Prince Regent, and in 1811 he was commissioned to develop Marylebone Park, a large area of farmland in north London which had recently reverted to crown ownership. It was here that Nash developed his master plan for Regent’s Park and its environs. Named after his patron, it was an ambitious piece of city planning, comprising the Regent’s Canal, a lake, a stretch of woodland, and, at its landscaped edges, elegant shopping arcades and groups of grandiose houses, varying in size and forming attractive crescents and terraces. Most of the brick houses were given stucco facades, a covering of durable plaster which, suitably marked and coloured, gave the illusion that the dwellings were made of stone. And within this gigantic scheme was the creation of Regent Street - xxxxxIn 1813 Nash was appointed deputy surveyor general, a post he held for two years. It was during this period that, working closely with the Prince Regent, he started rebuilding the Royal Pavilion which overlooked the seafront at Brighton in Sussex. On the whim of the Regent, he transformed what was a simple classical villa into a fanciful oriental palace, topped with exotic onion-

xxxxxIn 1813 Nash was appointed deputy surveyor general, a post he held for two years. It was during this period that, working closely with the Prince Regent, he started rebuilding the Royal Pavilion which overlooked the seafront at Brighton in Sussex. On the whim of the Regent, he transformed what was a simple classical villa into a fanciful oriental palace, topped with exotic onion- xxxxxAnd also proving excessively expensive was his next project, the repair and enlargement of what now came to be known as Buckingham Palace. This was originally a house constructed in the reign of James I, and it acquired its name when it was rebuilt by the Duke of Buckingham at the beginning of the 18th century. George III bought Buckingham House in 1761, but it was left to his son, the extravagant Prince Regent, to embark on a royal face-

xxxxxAnd also proving excessively expensive was his next project, the repair and enlargement of what now came to be known as Buckingham Palace. This was originally a house constructed in the reign of James I, and it acquired its name when it was rebuilt by the Duke of Buckingham at the beginning of the 18th century. George III bought Buckingham House in 1761, but it was left to his son, the extravagant Prince Regent, to embark on a royal face- xxxxxIncidentally, when working on Buckingham Palace in 1828 Nash designed a triumphal arch to commemorate the victories of Trafalgar and Waterloo, and to serve as an imposing ceremonial entrance to the palace -

xxxxxIncidentally, when working on Buckingham Palace in 1828 Nash designed a triumphal arch to commemorate the victories of Trafalgar and Waterloo, and to serve as an imposing ceremonial entrance to the palace -

xxxxxHumphry Repton (1752-

xxxxxHumphry Repton (1752- xxxxxHe worked successfully with Nash in providing garden schemes for a number of houses and cottages in Wales, but later, following his return to London, he quarrelled with him, claiming that the Mughal style of architecture that Nash used in the rebuilding of the Royal Pavilion at Brighton had been stolen from a design he himself had put forward. Later he chose to go into business with his son, John Addey Repton, a trained architect. During his career he published his ideas in a number of books, his major works being Sketches and Hints on Landscape Gardening in 1794, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening in 1803, and An Inquiry into the Changes of Taste in Landscape Gardening, three years later. He is credited with having invented the term “landscape gardening”. Illustrated here is his proposed garden scheme for Stoneleigh Abbey, Warwickshire.

xxxxxHe worked successfully with Nash in providing garden schemes for a number of houses and cottages in Wales, but later, following his return to London, he quarrelled with him, claiming that the Mughal style of architecture that Nash used in the rebuilding of the Royal Pavilion at Brighton had been stolen from a design he himself had put forward. Later he chose to go into business with his son, John Addey Repton, a trained architect. During his career he published his ideas in a number of books, his major works being Sketches and Hints on Landscape Gardening in 1794, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening in 1803, and An Inquiry into the Changes of Taste in Landscape Gardening, three years later. He is credited with having invented the term “landscape gardening”. Illustrated here is his proposed garden scheme for Stoneleigh Abbey, Warwickshire. xxxxxLike his contemporary John Nash, the Scottish civil engineer John Rennie (1761-

xxxxxLike his contemporary John Nash, the Scottish civil engineer John Rennie (1761- xxxxxRennie was born at Phantassie, near Haddington, East Lothian, and studied at Edinburgh University. He began his career as a millwright, and as from 1784 worked for the Scottish engineer James Watt for a number of years. During this time he much improved the machinery at the Boulton and Watt Albion mills in London, replacing wooden parts for those made of iron. He set up his own business in 1791, and it was from then that he became involved in building or improving docks, canals, harbours and bridges throughout Britain. This work, in which he pioneered the use of new materials and undertook vast and demanding projects, marked him out as one of the greatest civil engineers of his day.

xxxxxRennie was born at Phantassie, near Haddington, East Lothian, and studied at Edinburgh University. He began his career as a millwright, and as from 1784 worked for the Scottish engineer James Watt for a number of years. During this time he much improved the machinery at the Boulton and Watt Albion mills in London, replacing wooden parts for those made of iron. He set up his own business in 1791, and it was from then that he became involved in building or improving docks, canals, harbours and bridges throughout Britain. This work, in which he pioneered the use of new materials and undertook vast and demanding projects, marked him out as one of the greatest civil engineers of his day.  xxxxx…… Inx1807 Rennie collaborated with his fellow countryman and engineer Robert Stevenson (1772-

xxxxx…… Inx1807 Rennie collaborated with his fellow countryman and engineer Robert Stevenson (1772-