xxxxxAs we have seen, Napoleon became president of the Second Republic in 1848 -

EMPEROR NAPOLEON III 1852 -

xxxxxAs we have seen, it was following the revolution of July 1830 (W4), and the fall of the reactionary French king Charles X, that Louis Philippe, the so-

xxxxxAs we have seen, it was following the revolution of July 1830 (W4), and the fall of the reactionary French king Charles X, that Louis Philippe, the so-

xxxxxOn his departure, a national assembly dominated by the middle class was established, led initially by the politician and poet Alphonse de Lamartine, but for the workers of Paris this was not radical enough, and another popular rebellion broke out, known as the “June Days”. However, lacking the necessary leadership, it was ruthlessly crushed by the use of artillery, and in December a plebiscite elected a single chamber government with Louis-

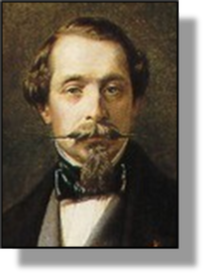

xxxxxCharles Louis Napoleon (illustrated), a son of Napoleon Bonaparte’s brother Louis, was born in 1808, at the time when his father was king of Holland. After the fall of his uncle, he spent much of his youth in exile with his mother. She, being a stepdaughter of Napoleon I and thus a Bonaparte, was banished from France, and they eventually found a home at Arenenberg Castle in Switzerland. His education, which was mostly by private tutors, gave him a keen interest in history, and his visits to Germany and Italy inspired him with the idea of national independence. At one time, as a member of the Carbonari, he even took part in an Italian plot against the papal government, and a rebellion in the central states. Both were unsuccessful.

xxxxxCharles Louis Napoleon (illustrated), a son of Napoleon Bonaparte’s brother Louis, was born in 1808, at the time when his father was king of Holland. After the fall of his uncle, he spent much of his youth in exile with his mother. She, being a stepdaughter of Napoleon I and thus a Bonaparte, was banished from France, and they eventually found a home at Arenenberg Castle in Switzerland. His education, which was mostly by private tutors, gave him a keen interest in history, and his visits to Germany and Italy inspired him with the idea of national independence. At one time, as a member of the Carbonari, he even took part in an Italian plot against the papal government, and a rebellion in the central states. Both were unsuccessful.

xxxxxIn 1832 Emperor Napoleon’s only son, the Duke of Reichstadt, died, and the young Napoleon, seeing himself as the rightful claimant to the imperial heritage, began to make his bid for power. His Reveries politiques, published the same year, openly claimed that only the return of an Emperor could restore France to its former greatness. Then four years later, in October 1836, he added action to words and attempted to gain the support of the Strasbourg garrison to overthrow Louis Philippe. The attempt failed and he was exiled to the United States. He returned to Switzerland the following year to see his mother, then on her deathbed, but was banned in 1838, and had to take refuge in England.

xxxxxIt was in England that he published his Des idées napoléoniennes, claiming once again that he was the man to continue the work begun by the great Emperor Napoleon. He would bring order, protect the rights of the people, and make France a powerful industrial and commercial nation, all in accordance with what he called “the Napoleonic idea”. Then, once again, following words by action, in August 1840, at the head of some 50 followers, he landed at Boulogne to gain the support of the town’s garrison. It was not forthcoming. He was arrested and sentenced to “permanent confinement” in Ham Castle. From here, however, he continued to canvass for support, writing newspaper articles and pamphlets in an attempt to curry favour with both the right and left of the political divide. Then in May 1846 he managed to escape from his prison and make his way back to England.

xxxxxThe opportunity he was waiting for came in February 1848 with the outbreak of the Paris rebellion and the overthrow of Louis Philippe. Following the fall of the provisional government -

xxxxxBut with a name like Napoleon, being president was not enough. Having at last gained a position of power, he began to hand out key posts to his followers in the army as well as the government, clamp down on the activities of known Republicans, and travel across the country to gain widespread popularity. By 1851 he was firmly entrenched in his new appointment, but by then time was running out. The office of president was confined to a four-

xxxxxBut with a name like Napoleon, being president was not enough. Having at last gained a position of power, he began to hand out key posts to his followers in the army as well as the government, clamp down on the activities of known Republicans, and travel across the country to gain widespread popularity. By 1851 he was firmly entrenched in his new appointment, but by then time was running out. The office of president was confined to a four-

xxxxxIn order to strengthen his regime in the eyes of his people and the world, Napoleon soon embarked upon a series of military enterprises. As we shall see, he joined in the Crimean War in 1854 as an ally of Great Britain, and in 1859 went to the aid of the Italians in their struggle for independence from the Austrians. The Battle of Solferino in which Napoleon personally commanded his army, was a victory for the French and, as a reward, led to the annexation of Savoy and Nice in 1860. At home, meanwhile, he remained very much an autocratic ruler. However, despite repressive measures, opposition to his regime from both republicans and socialists continued and increased throughout the 1850s.

xxxxxThis growing opposition to his despotic policy at home eventually forced him to give way on a number of issues. Some headway was made towards the setting up of parliamentary government, for example, and liberal reforms encouraged economic growth and an increase in international trade. However, as from the early 1860s his foreign policy was decidedly less successful, marked, as we shall see, by a disastrous attempt to set up a French-

xxxxxIncidentally, Louis-

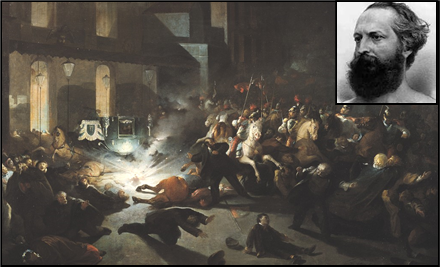

xxxxx…… Inx1858 an assassination attempt was made on Napoleon’s life by an Italian revolutionary named Felice Orsini (1819-

xxxxx…… Inx1858 an assassination attempt was made on Napoleon’s life by an Italian revolutionary named Felice Orsini (1819-

Va-

Acknowledgements

Louis Philippe: by the German painter Franz Xaver Winterhalter (1805-

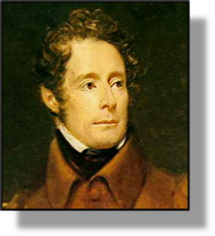

xxxxxThe French politician and poet Alphonse de Lamartine (1790-

Including:

Alphonse de

Lamartine

xxxxxThe French politician and poet Alphonse de Lamartine was born into an aristocratic family at Macon, 45 miles north of Lyons, in 1790. He was educated at the Jesuit College of Belley and then, in keeping with his family tradition, became a member of the bodyguard of Louis XVIII in 1814 at the age of 24. He went to live in Switzerland during Napoleon’s Hundred Days, but returned to France after the restoration of the Bourbons. He entered the diplomatic service in 1820, and, after a distinguished career, was elected to

xxxxxThe French politician and poet Alphonse de Lamartine was born into an aristocratic family at Macon, 45 miles north of Lyons, in 1790. He was educated at the Jesuit College of Belley and then, in keeping with his family tradition, became a member of the bodyguard of Louis XVIII in 1814 at the age of 24. He went to live in Switzerland during Napoleon’s Hundred Days, but returned to France after the restoration of the Bourbons. He entered the diplomatic service in 1820, and, after a distinguished career, was elected to  the Chamber of Deputies in 1833, during the reign of Louis Philippe. There he quickly gained a reputation as an outstanding orator and a man of the people, deeply concerned with the plight of the working class, and speaking out in favour of republican liberty. He served as the member for Macon as from 1837, and gained national recognition with his publication in 1847 of the History of the Girondins, a work which undoubtedly fanned the flames of popular rebellion. When the revolution broke out the following year, he became one of its principal leaders and, under the provisional government, was appointed minister of foreign affairs.

the Chamber of Deputies in 1833, during the reign of Louis Philippe. There he quickly gained a reputation as an outstanding orator and a man of the people, deeply concerned with the plight of the working class, and speaking out in favour of republican liberty. He served as the member for Macon as from 1837, and gained national recognition with his publication in 1847 of the History of the Girondins, a work which undoubtedly fanned the flames of popular rebellion. When the revolution broke out the following year, he became one of its principal leaders and, under the provisional government, was appointed minister of foreign affairs.

xxxxxFor the radicals, however, this hotchpotch of a government was far too moderate, and fighting broke out again. The rebellion was quickly crushed in June, but by this time, as we have seen, Emperor Napoleon's nephew, Louis Napoleon (the future Napoleon III), was making his bid for power. Playing on his legendary name, and promising to restore France to its former greatness, he gained a landslide victory when the election for a president of the Second Republic was held in the December. Lamartine put himself up as a candidate, but he won very few votes and, disillusioned, decided to retire from public life.

xxxxxDespite the leading part that he played as a statesman in the 1848 revolution, Lamartine is mostly remembered today for his contribution to French literature. He came to prominence as a poet with his Poetic Meditations of 1820 and the sequel New Meditations, written in Italy three years later. These works, together with his Poetical and Religious Harmonies, published in 1830, established his reputation as one of the outstanding leaders of the French romantic movement. Full of deep personal feelings, and clothed in a pensive, sometimes melancholy tone, his verse possessed a gentle, melodious quality which won instant acclaim. Such works were in marked contrast to the sterile abstractions of poetic classicism, and were inspired above all by a love of nature, an aspect reminiscent of the poems by the Englishman William Wordsworth. He was elected to the Académie Française in 1829.

xxxxxOther works included The Death of Socrates in 1824, The Last Song of Childe-

xxxxxFollowing his retirement from public service, Lamartine fell on hard times, caused entirely by his need to support his sisters. In an attempt to make ends meet, he was obliged to keep writing for the next twenty years. Amongst his prose work was a series of novels, including Geneviève and The Stonecutter of Saint Point, a number of historical works, such as The History of the Restoration, completed in 1852, and histories of Russia and Turkey, and numerous biographies and short stories. In 1868 he was granted a generous pension, but by then he was worn out, and he died in Paris the following year.

xxxxxIncidentally, two of his novels were autobiographical and concerned his love for two women he had known as a young man. Graziella, published in 1852, was the fictitious name for Antoniella, a young girl whom he had met in 1812 and who had died three years later, and Raphael (Rafael), written in 1849, was an account of his love for Julie Charles, whom he had met in 1816. She was in poor health and, after her death the following year, Lamartine dedicated a number of verses to her, including his poem Le Crucifix. ……

xxxxxIncidentally, two of his novels were autobiographical and concerned his love for two women he had known as a young man. Graziella, published in 1852, was the fictitious name for Antoniella, a young girl whom he had met in 1812 and who had died three years later, and Raphael (Rafael), written in 1849, was an account of his love for Julie Charles, whom he had met in 1816. She was in poor health and, after her death the following year, Lamartine dedicated a number of verses to her, including his poem Le Crucifix. ……

xxxxx…… In 1820, while working as attaché to the French embassy in Naples, Lamartine met and married a wealthy English woman named Maria Ann Birch. Sadly, their only son, born in Rome the following year, did not survive infancy, and their only daughter, Julia, died in Beirut in December 1832.