xxxxxAs we have seen, it was in 1852 (Va) that Charles Louis Napoleon, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, was proclaimed Emperor of France as Napoleon III. At first his domestic policy was brutally autocratic, but by 1860 he began to introduce liberal reforms aimed at a form of parliamentary democracy. Furthermore, he modernised the nation by a series of public works, and introduced an enlightened policy towards free trade and the development of French agriculture and industry. In foreign affairs, too, he began by making an impressive start. In 1855 he emerged triumphant from the Crimean War and, four years later, his victory against the Austrians at the Battle of Solferino helped towards the unification of Italy. However, adventures further afield during the 1860s proved a drain on his country’s resources. He set up a colony in Indochina, attempted to take over Korea, and then suffered a humiliating defeat in North America. Having established Maximilian, a Habsburg prince, upon the throne of Mexico in 1862, the republican opposition, aided by the United States, began to gain the upper hand and forced him to withdraw his troops in 1866. As we shall see, his Empire eventually came to an end with the defeat of France in the Franco-

NAPOLEON III OF FRANCE 1852 -

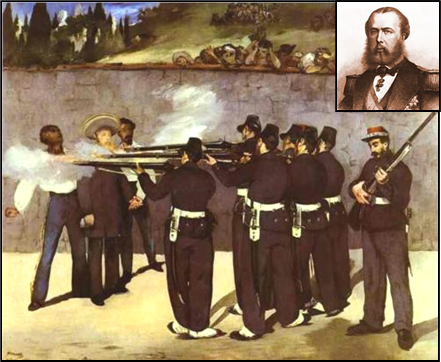

FAILURE OF HIS MEXICAN ADVENTURE 1862 -

Acknowledgements

Napoleon III: detail, after the German painter Franz Xaver Winterhalter (1806-

xxxxxAs we have seen (1852 Va), it was in December 1848, following the overthrow of King Louis Philippe, that Charles Louis Napoleon, son of Napoleon Bonaparte’s brother Louis, swept to victory as president of the Second Republic. Having made two previous, highly unsuccessful attempts to seize power in France, it was third time lucky for the young Napoleon. However, as rightful claimant to the imperial heritage, being president was clearly not enough. In 1851, acting on a trumped up excuse that the nation was in danger from an internal conspiracy, he seized complete control of the country and ruthlessly crushed any Republican or socialist opposition. Then in December 1852, not without a great deal of public support, he was proclaimed Emperor of France. The Bonapartes were back in power and the Second Empire had begun.

xxxxxAs we have seen (1852 Va), it was in December 1848, following the overthrow of King Louis Philippe, that Charles Louis Napoleon, son of Napoleon Bonaparte’s brother Louis, swept to victory as president of the Second Republic. Having made two previous, highly unsuccessful attempts to seize power in France, it was third time lucky for the young Napoleon. However, as rightful claimant to the imperial heritage, being president was clearly not enough. In 1851, acting on a trumped up excuse that the nation was in danger from an internal conspiracy, he seized complete control of the country and ruthlessly crushed any Republican or socialist opposition. Then in December 1852, not without a great deal of public support, he was proclaimed Emperor of France. The Bonapartes were back in power and the Second Empire had begun.

xxxxxFor the next eight years or so, having despatched political prisoners to penal colonies, Napoleon kept a firm, autocratic grip on home affairs. Nonetheless, opposition to his regime grew, fuelled by a deterioration in the country’s economic condition, and by 1860 he saw the need to make some concessions towards a more representative form of parliamentary government. Within ten years, in fact, in fulfilment of his promise to provide “reasonable freedom”, France had moved some way towards a constitutional monarchy, though in all matters the Emperor retained ultimate authority.

xxxxxAnd within that decade Napoleon played a prominent part in using state funds to institute a vast programme of public works -

xxxxxBut whilst his domestic policy achieved a substantial measure of success, his foreign policy brought about his downfall. In his first years as Emperor he looked for military glory, like his uncle before him, and, in the short term, he found it. Allied with Great Britain he emerged triumphant from the Crimean War in 1855, and in his support for Italian independence he defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Solferino in 1859, gaining respect as a field commander and adding the territories of Savoy and Nice to his empire. But from the early 1850s he also embarked upon a series of colonial adventures, and these stretched the country’s military resources. These romantic forays included an unsuccessful attempt to modernise Algeria -

xxxxxOvershadowingxthese colonial adventures, however, was his disastrous attempt to create a French-

xxxxxOvershadowingxthese colonial adventures, however, was his disastrous attempt to create a French- went well, and Maximilian was duly installed as “Emperor” in April 1864. However,xwith the end of the American Civil War the following year, the United States began to send aid to the republican cause, led by Benito Juarez (1806-

went well, and Maximilian was duly installed as “Emperor” in April 1864. However,xwith the end of the American Civil War the following year, the United States began to send aid to the republican cause, led by Benito Juarez (1806-

xxxxxMeanwhile In Europe, where security mattered most, Napoleon totally misjudged both the political and military situation. The swift victories achieved by Prussia in their wars with the Danes and the Austrians, and the move these achieved towards German unification, should have alerted the French government to a changing and threateni ng situation, but the warning signs went virtually unheeded. Indeed, Napoleon, convinced of France’s invincibility, and determined to cut Prussia down to size, played into the hands of the Prussian foreign minister, Otto von Bismarck. Provoked into declaring war following a dispute over the candidature for the Spanish throne, the Franco-

ng situation, but the warning signs went virtually unheeded. Indeed, Napoleon, convinced of France’s invincibility, and determined to cut Prussia down to size, played into the hands of the Prussian foreign minister, Otto von Bismarck. Provoked into declaring war following a dispute over the candidature for the Spanish throne, the Franco-

xxxxxOn his release, he spent his last years with his wife and young son at Chislehurst, England, ever haunted by his military failure, and the collapse of the country he endeavoured to serve so well. He died in January 1873, not living to see the death of his only legitimate son Eugene, killed in 1879 while fighting in the British army against a Zulu uprising in southern Africa. In 1873 Napoleon was buried at the Catholic Church at Chislehurst, but i n 1888 his body, and that of his son, were transferred to an Imperial Crypt at St. Michael’s Abbey in Farnborough, Hampshire, a resting place provided by his wife Eugenie.

n 1888 his body, and that of his son, were transferred to an Imperial Crypt at St. Michael’s Abbey in Farnborough, Hampshire, a resting place provided by his wife Eugenie.

xxxxxUnderstandably, Napoleon attracted a great deal of adverse criticism. Victor Hugo, one of his harshest critics, dubbed him Napoleon le Petit, and Karl Marx described his reign as nothing short of a farce. In fact, he did much to enhance the status of France, both by his domestic policy and his early ventures on the world stage, but in the end, it must be said, he did bring about the total collapse of the proud nation under his charge, and that fact was never likely to be forgotten or forgiven.

xxxxxIncidentally, the establishment of a French colony in the southern part of Vietnam in 1867 -

Vb-