xxxxxAs we have seen, it was in 1848 (Va) that the German social philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published the Communist Manifesto, calling for the workers of the world to unite and overthrow the capitalist system. Because of the revolutions which broke out across Europe later that year, Marx was obliged to take refuge in London. There he became the virtual leader of the First International, organised by the International Workers’ Association in 1864. Under his guidance this organisation flourished, but in 1871 he came out strongly in favour of the Paris Commune of that year, and this brought into the open the deep divisions within the movement. He managed to defeat the anarchists who, led by the German socialist Mikhail Bakunin, wished to take direct action against the capitalist governments, but this brought about the collapse of the International in 1876. Meanwhile Marx spent long hours writing up his major work Das Kapital (Capital), the first volume of which was published in 1867. In this he argued that the capitalist system made the bourgeoisie progressively wealthy by exploiting the working man, forcing him to labour long for little reward. It was inevitable, he claimed, that the working class would overthrow capitalism by violent means and introduce a communist system based on common ownership of the means of production and a classless society. Marx died in 1883 and it was left to his collaborator Friedrich Engels to edit his friend’s notes and produce the additional two volumes in 1885 and 1894. Marx was one of the most influential socialist thinkers of all time, and his theories, inciting as they did a class struggle, were to have an enormous impact upon the history of the 20th century in Europe and, given time, across most parts of the world.

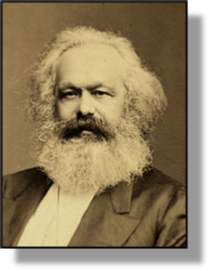

KARL MARX -

Acknowledgements

Marx: detail, by

the London photographer John Mayall (1813-

xxxxxAs we have seen, it was in 1848

(Va) that the

two German social philosophers, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels,

published the Communist Manifesto. In this they argued that the

age-

xxxxxAs we have seen, it was in 1848

(Va) that the

two German social philosophers, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels,

published the Communist Manifesto. In this they argued that the

age-

xxxxxAs noted

earlier, for the next fifteen years Marx and his family were

poverty-

xxxxxThroughout these years his main task was preparing data for his major work Das Kapital (Capital). He spent many hours in the British Museum reading up on social and economic history to develop his theories, and his first book, Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, written in 1859, was an examination of what he called “the system of bourgeois economy”, a study central to his materialistic conception of history. Such research took up much of his time, but It was inevitable that Marx would be drawn into active politics. Having rejoined the Communist League, he urged the setting up of “revolutionary workers’ governments”, but cautioned against precipitate action, arguing that a transition period of fifteen to fifty years of strife would be necessary to bring about change and equip the working man for political power. When the League was dissolved in 1852, Marx maintained contact with revolutionists in Britain and across the continent, and it was due in part to his influence that in September 1864 the International Workingmen’s Association was formed, sparked off by a visit to London of a group of French workers.

xxxxxMarx was not a founder member but, once elected to

the General Council, he soon became the organisation’s leading

spirit, drawing up the Association’s rules, outlining its aims,

and overseeing the work of its committees. His commitment to the

cause, and his skills as a journalist paid off. Under his tactful

guidance the First International, as the Association came to be

known, grew in strength. By 1867 there were delegates from six

countries -

xxxxxMarx was not a founder member but, once elected to

the General Council, he soon became the organisation’s leading

spirit, drawing up the Association’s rules, outlining its aims,

and overseeing the work of its committees. His commitment to the

cause, and his skills as a journalist paid off. Under his tactful

guidance the First International, as the Association came to be

known, grew in strength. By 1867 there were delegates from six

countries -

xxxxxThese

disagreements came to the surface in 1871. In that year the

establishment of the Paris Commune, following close on the

armistice which ended the Franco-

xxxxxInxEurope, not

surprisingly, Marx became the symbol of the revolutionary spirit,

but in the First International his public stance only served to

exacerbate the antagonisms within the movement. A number of

English trade unionists, for example, following the Reform Bill of

1867, considered that changes could be accomplished via the ballot

box, whilst in stark contrast, a large group of anarchists, led by

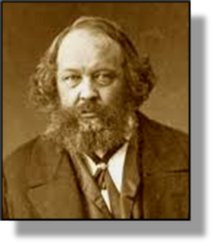

the Russian revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin (1814-

xxxxxInxEurope, not

surprisingly, Marx became the symbol of the revolutionary spirit,

but in the First International his public stance only served to

exacerbate the antagonisms within the movement. A number of

English trade unionists, for example, following the Reform Bill of

1867, considered that changes could be accomplished via the ballot

box, whilst in stark contrast, a large group of anarchists, led by

the Russian revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin (1814-

xxxxxWith the collapse of the First International, Marx

returned to what he saw as his overriding task, the completion of

his monumental work Das Kapital. This “Bible of the Working Class” aimed to analyse

in detail the history of capitalism in order to highlight the

weaknesses of the capitalist system, its gradual self-

xxxxxWith the collapse of the First International, Marx

returned to what he saw as his overriding task, the completion of

his monumental work Das Kapital. This “Bible of the Working Class” aimed to analyse

in detail the history of capitalism in order to highlight the

weaknesses of the capitalist system, its gradual self-

xxxxxAdopting

what he termed the materialist conception of history, Marx argued

that under capitalism labour was nothing more than a commodity

that could be exploited to maximise profit. Whereas a machine had

a limit to its capacity, the existence of a reserve army of

unemployed “hands”, eagerly seeking a subsistence wage, provided

what Marx called a “surplus value”, an excess product which

provided additional profit for the capitalists or bourgeoisie,

those who controlled the political and economic power of the

nation. This division between those in society who ruled and were

wealthy, and those who were oppressed and poverty-

xxxxxBut Marx never saw the publication of the remainder of his masterpiece. During the last decade of his life his health declined fairly rapidly, and he suffered from bouts of depression. Nevertheless he continued to show an interest in working class movements at home and abroad. In a letter written in 1875, for example, (later published as Critique of the Gotha Programme), he took the German socialists to task for being willing to cooperate with their government, and he was delighted, so we are told, to learn of the assassination of Alexander II, the first sign, as he rightly saw it, of a peasant revolt to overthrow Tsarism. He attended health resorts for a time, and on one occasion travelled to Algeria, but he never recovered from his wife’s death in 1881, and following the death of his eldest daughter Jenny in January 1883, he died just two months later and was buried in Highgate Cemetery in North London. It was left to Friedrich Engels, his devoted collaborator, to edit the copious notes left by Marx and produce from these the second and third volumes of Capital, published in 1885 and 1894.

xxxxxMarx  was

one of the most influential socialist thinkers of all time. His Das Kapital, -

was

one of the most influential socialist thinkers of all time. His Das Kapital, -

xxxxxIncidentally, manuscripts and notes found after Marx’s death

showed that he had a fourth volume of Das

Kapital in mind. These writings were edited by the German

socialist Karl Kautsky

(1854-

xxxxx…… Marx’s imposing tomb in Highgate Cemetery, complete with portrait bust, was built by the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1954. It bears the inscription: “Workers of all lands unite”. There is an impressive statue of Marx in Moscow, and combined statues of Marx and Engels in Berlin and Budapest. ……

xxxxx…… The Internationale, the famous socialist and communist anthem, was

originally a French poem written by the French socialist Eugène Pottier (1816-

Including:

Das Kapital and

Friedrich Engels

Vb-

xxxxxAs we have

seen (1848 Va),

Friedrich Engels

(1820-

xxxxxAs we have seen (1848 Va), Friedrich Engels (1820-

xxxxxAs we have seen (1848 Va), Friedrich Engels (1820-

xxxxxThe

Manifesto itself had little or no immediate effect on the current

social and political scene -

xxxxxDuring this

period and beyond, Engels wrote a large number of newspaper

articles encouraging the communist movement in Europe -

xxxxxAfter Marx’s death in 1883 Engels continued to serve

his friend as the foremost theorist and apologist of Marxism

He assiduously maintained contact with leaders of the

communist movement worldwide, and he devoted the next ten years to

editing a mass of manuscripts and a vast quantity of rough drafts

in order to compile and complete the second and third volumes of Das Kapital, published in 1885 and 1894. And

to these years belongs three works of particular value to the

cause, The Origin of the Family, Private

Property and the State, Ludwig

Feuerbach and the Outcome of Classical German Philosophy,

and Socialism: Utopian and Scientific,

the last named setting out the materialist conception of history

and denouncing the capitalist machine that kept the workers under

control. In 1870 he moved to London and it was there, in 1895,

that he died of cancer.

xxxxxAfter Marx’s death in 1883 Engels continued to serve

his friend as the foremost theorist and apologist of Marxism

He assiduously maintained contact with leaders of the

communist movement worldwide, and he devoted the next ten years to

editing a mass of manuscripts and a vast quantity of rough drafts

in order to compile and complete the second and third volumes of Das Kapital, published in 1885 and 1894. And

to these years belongs three works of particular value to the

cause, The Origin of the Family, Private

Property and the State, Ludwig

Feuerbach and the Outcome of Classical German Philosophy,

and Socialism: Utopian and Scientific,

the last named setting out the materialist conception of history

and denouncing the capitalist machine that kept the workers under

control. In 1870 he moved to London and it was there, in 1895,

that he died of cancer.

xxxxxEngel’s name is inextricably linked with that of

Marx, and it is perhaps because of this that his personal

contribution to the birth and development of communism has not

always received the acknowledgement it deserves. It is doubtless

true that the Communist Manifesto was largely the work of Marx,

but Engels played a significant role in formulating the

revolutionary social philosophy which goes by the name of Marxism,

based upon a materialistic interpretation of history. He had

first-

xxxxxEngel’s name is inextricably linked with that of

Marx, and it is perhaps because of this that his personal

contribution to the birth and development of communism has not

always received the acknowledgement it deserves. It is doubtless

true that the Communist Manifesto was largely the work of Marx,

but Engels played a significant role in formulating the

revolutionary social philosophy which goes by the name of Marxism,

based upon a materialistic interpretation of history. He had

first-

xxxxxIncidentally, although German by birth, Engels had very much the

ways and demeanour of an English gentleman. However, he had a

ruthless, abrasive side to his character and this made him a

number of enemies. But Marx would never hear any criticism of his

friend -

xxxxx…… In 1889 Engels played a part in the formation of the Second International, remembered in particular for its declaration of May 1st as International Labour Day. The movement proved more successful than its predecessor, but it was dissolved in 1916 during the First World War.