xxxxxIn 1834 six English farm workers at Tolpuddle, Dorset, having formed a Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers, demanded higher wages. The government, however, had just quelled the so-called “Captain Swing Riots”, a violent rebellion of social discontent which had caused much damage across the whole of southern England. Although the forming of unions had been made legal by the Reform Act of 1832, it arrested the six men and, learning that they had sworn an oath as members of their Society, charged them with an obsolete law banning such a practice. All were found guilty and sentenced to transportation to Australia for a period of seven years. But the public were outraged at the severity of the sentences, and the means used to bring about the convictions. There was protest throughout the country, and mass meetings were held in London. Eventually the government was forced to give in, and all six men were pardoned in March 1836. They were welcomed home as heroes, and since that day the little village of Tolpuddle has been seen as a place of special importance in the history of the British trade union movement. And among those who supported the “Tolpuddle Martyrs” were future members of Chartism, a movement which, as we shall see (1838 Va), was to play a vital role in political reform.

THE TOLPUDDLE MARTYRS 1834 (W4)

Acknowledgements

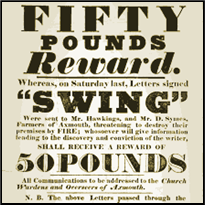

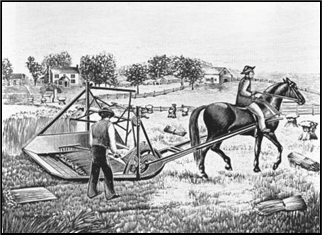

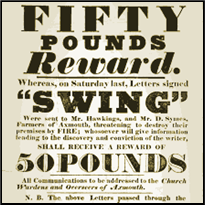

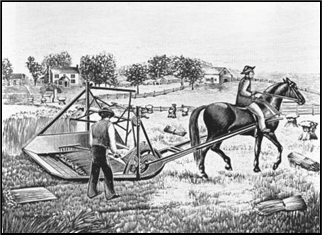

Tolpuddle: by the English artist William Burges (1827-1881) – Tolpuddle Martyrs’ Museum, Tolpuddle, Dorset, England. Martyrs: by the English illustrator Clifford Harper – Tolpuddle Martyrs’ Museum, Tolpuddle, Dorset, England. Festival: press release for 2014 by the Tolpuddle Martyrs’ Museum, Tolpuddle, Dorset, England. Riots: a contemporary etching, artist unknown. Reaping Machine: contained in Cyrus Hall McCormick and the Reaper by the American historian Reuben Gold Thwaites (1853-1913), published 1909, artist unknown – Stuhr Museum of the Prairie Pioneer, Grand Island, Nebraska, USA.

xxxxxIt was in the early 1830s that six English farm labourers from Tolpuddle, a village near Dorchester in Dorset, formed a Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers. Established as a lodge of the newly formed Grand National Consolidated Trades Union - the brainchild of the social reformer Robert Owen - it aimed to improve their wages, which, over the past three years had slumped from nine to six shillings a week. Led by George Loveless, a Methodist lay preacher, they agreed on an entrance fee of five pence and (and this proved their downfall) they swore an oath of allegiance to the Society. Membership increased rapidly, and early in 1834 the men made it known that they would withdraw their labour if their pay were not increased.

xxxxxIt was in the early 1830s that six English farm labourers from Tolpuddle, a village near Dorchester in Dorset, formed a Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers. Established as a lodge of the newly formed Grand National Consolidated Trades Union - the brainchild of the social reformer Robert Owen - it aimed to improve their wages, which, over the past three years had slumped from nine to six shillings a week. Led by George Loveless, a Methodist lay preacher, they agreed on an entrance fee of five pence and (and this proved their downfall) they swore an oath of allegiance to the Society. Membership increased rapidly, and early in 1834 the men made it known that they would withdraw their labour if their pay were not increased.

xxxxxThe Reform Act of 1832, just two years earlier, had actually made legal the forming of unions, but the Whig government, alarmed at the consequences of such a threat, was determined to find a means of banning this society. In some respects, their stance was understandable. At that time there was much social unrest throughout the country, and only two years earlier the whole of southern England had seen much damage done by the so-called “Captain Swing” riots, a violent rebellion of working class discontent. As a result, in March 1834 the six leaders were arrested, marched in chains to Dorchester, and put before a patently unsympathetic judge and jury. There, acting on government advice, they were charged with contravening an obsolete law which forbade the “administering of unlawful oaths” - last used in 1797 (G3b) during the naval mutinies at Spithead and Nore. All six were found guilty and sentenced to transportation to an Australian penal colony for a period of seven years. It was not, the judge confessed, for anything they had done, “but as an example to others”. The severity of these sentences broke the back of the GNCTU, but the six men became national heroes, and known nationally as the “Tolpuddle Martyrs”. There were protest meetings across the country, and large scale demonstrations in London, said to number 40,000 people.

xxxxxDespite such widespread disapproval, the government stood firm, and George Loveless and his brother James, the prime movers in the forming of the union, together with James Brine, James Hammett, Thomas Stanfield, and his son, John, arrived in Sydney to serve their sentences in August 1834. But the matter did not end there. Protest continued. People across England were outraged not only at the severity of the sentences, but also in the way the case had been manipulated so as to ensure convictions. Eventually a campaign of demonstrations and the sending of petitions to the Home Secretary, Lord John Russell - who was himself sympathetic to the martyrs’ cause - proved successful. All six were given conditional pardons in June 1835, and full pardons in March 1836. They were greeted as heroes on their return to England. In the event, only one, James Hammett, stayed in Tolpuddle. Three of the others emigrated to Canada, settling in London, Ontario, where a monument was erected in their honour.

xxxxxDespite such widespread disapproval, the government stood firm, and George Loveless and his brother James, the prime movers in the forming of the union, together with James Brine, James Hammett, Thomas Stanfield, and his son, John, arrived in Sydney to serve their sentences in August 1834. But the matter did not end there. Protest continued. People across England were outraged not only at the severity of the sentences, but also in the way the case had been manipulated so as to ensure convictions. Eventually a campaign of demonstrations and the sending of petitions to the Home Secretary, Lord John Russell - who was himself sympathetic to the martyrs’ cause - proved successful. All six were given conditional pardons in June 1835, and full pardons in March 1836. They were greeted as heroes on their return to England. In the event, only one, James Hammett, stayed in Tolpuddle. Three of the others emigrated to Canada, settling in London, Ontario, where a monument was erected in their honour.

xxxxxThe events surrounding the Tolpuddle Martyrs played a key role in the development of the modern trade union movement in Britain, and in the general struggle for fairer wages and better working conditions - though improvements were not quick in the coming. And taking part in the demonstrations that they aroused were future members of Chartism, a movement which, as we shall see (1838 Va), was to play a vital part in political reform, with its demand for universal suffrage and vote by ballot.

xxxxxIncidentally, it is said that when discussing their proposed union the martyrs would often meet under a giant sycamore tree which stood on the village green in Tolpuddle. Today, this tree - dating from the 1680s and now much reduced for safety reasons - has become a symbol of the birth of the trade union movement. ……

xxxxx…… In 1934, on the centenary of their trial, the British Trades Union Congress (the TUC) built six memorial cottages in the village, and also established the Tolpuddle Martyrs Museum. The house of Thomas Standfield, where the leaders often met, can still be seen, as can the court house where the men were tried, now part of the local council offices in Dorchester. ……

xxxxx…… Every year in July the TUC organises a festival in the village during which members of various trade unions march past the village green. Thousands attend this event, including many from trade union movements across the world. In 1934 the London draper Sir Ernest Debenham had a memorial seat and shelter erected on the green, and in 2001 a sculpture of the martyrs was placed in front of the museum.

Including:

The “Captain Swing Riots”

and Cyrus Hall McCormick

W4-1830-1837-W4-1830-1837-W4-1830-1837-W4-1830-1837-W4-1830-1837-W4-1830-1837-W4

xxxxxThe government’s reaction to the demands of the Tolpuddle farm labourers in 1834 must be seen against the widespread violence of the so-called “Captain Swing” Riots which broke out in Kent in 1830. Aimed at increasing the wages of farmhands and providing work for the many unemployed, they had spread across the whole of southern England by the following year. Houses, barns and hay-ricks were set on fire, farm machinery was destroyed, and many landowners were forced to hand over money and increase the wages of their workers. When the riots were eventually subdued the punishment meted out was severe. Nine men were sentenced to death, over 450 were transported to penal colonies, and some 400 received prison sentences. Such, then, was the background against which the government was confronted with fresh demands for wage increases. The name of the riots appears to come from a make-believe leader who wrote a series of threatening letters to landowners, signed with the word “Swing”.

xxxxxAs noted earlier, one of the factors which influenced the government’s reaction to the labour movement set up at Tolpuddle in the early 1830s was the so-called “Captain Swing” Riots. Soldiers and sailors returning from the Napoleonic Wars - put at 250,000 - had considerably increased the number of men seeking work, especially in southern England, and there were thousands of families living close to starvation and deep in debt. This situation had not only outstripped the amount of poor relief available - never plentiful - but it had also served to deflate the wages of those who were in work, adding to the problem.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

xxxxxThe riots broke out in Kent in June 1830, moved into Surrey and Sussex, and by the end of 1831 had spread across the whole of southern England, including Hampshire, Dorset, Wiltshire, Berkshire and Buckinghamshire. Houses, barns and hay-ricks were set on fire, and machinery (especially threshing machines) were destroyed. A large number of landowners were threatened with violence, and many gave money to save their property from being destroyed. The military were called in, but often arrived too late to stop the acts of violence. Eventually, however, a large number of arrests were made and the punishment metered out was severe. Nine men were sentenced to death, over 450 were transported to penal colonies, mostly for arson, and a further 400 were given prison sentences of varying lengths. In the end, little was gained from the uprising. A number of farmers did increase their wages, but some of these made reductions once the crisis was over. And it was against this background of violence and intimidation that, in 1834, the Whig government was confronted with the demands of a group of farm labourers from Tolpuddle in Dorset, a county which had already given the administration a large amount of trouble.

xxxxxThe riots broke out in Kent in June 1830, moved into Surrey and Sussex, and by the end of 1831 had spread across the whole of southern England, including Hampshire, Dorset, Wiltshire, Berkshire and Buckinghamshire. Houses, barns and hay-ricks were set on fire, and machinery (especially threshing machines) were destroyed. A large number of landowners were threatened with violence, and many gave money to save their property from being destroyed. The military were called in, but often arrived too late to stop the acts of violence. Eventually, however, a large number of arrests were made and the punishment metered out was severe. Nine men were sentenced to death, over 450 were transported to penal colonies, mostly for arson, and a further 400 were given prison sentences of varying lengths. In the end, little was gained from the uprising. A number of farmers did increase their wages, but some of these made reductions once the crisis was over. And it was against this background of violence and intimidation that, in 1834, the Whig government was confronted with the demands of a group of farm labourers from Tolpuddle in Dorset, a county which had already given the administration a large amount of trouble.

xxxxxThe name given to the riots remains something of a mystery. It seems to have come from the name adopted by the leaders of the revolt in order to hide their identities. They signed their threatening letters “Swing” - doubtless an indication as to what would happen to those who did not give into their demands - and added “Captain” to show they were one of the leaders. From this came the mythical figure “Captain Swing”, the man who allegedly instigated and planned the campaign.

xxxxxIncidentally, we are told that in November 1830 the boys at Eton College sent a “Swing” letter to their headmaster to protest about the excessive use of the school’s “thrashing machine”! ……

xxxxx…… A few years after the “Captain Swing” Riots, the introduction of new farming machinery severely reduced the need for manual workers. In 1831 the American inventor Cyrus Hall McCormick (1809-1884) came up with his advanced reaping machine (illustrated). It was operated by two men and one or two horses, and was capable of cutting as much corn as sixteen men using reap hooks. For some years McCormick, the son of a Virginian farmer, confined his machine to his home state, and was involved in long legal disputes with rival manufacturers.

xxxxx…… A few years after the “Captain Swing” Riots, the introduction of new farming machinery severely reduced the need for manual workers. In 1831 the American inventor Cyrus Hall McCormick (1809-1884) came up with his advanced reaping machine (illustrated). It was operated by two men and one or two horses, and was capable of cutting as much corn as sixteen men using reap hooks. For some years McCormick, the son of a Virginian farmer, confined his machine to his home state, and was involved in long legal disputes with rival manufacturers.

xxxxxHowever, in 1847 he opened a factory in Chicago. There, using mass production methods and offering payment by instalments and an after-sales service, his business became highly successful. In 1851 the machine, by then much improved, was put on display at the Great Exhibition in London and this brought orders from European farmers.

xxxxxIt was in the early 1830s that six English farm labourers from Tolpuddle, a village near Dorchester in Dorset, formed a Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers. Established as a lodge of the newly formed Grand National Consolidated Trades Union -

xxxxxIt was in the early 1830s that six English farm labourers from Tolpuddle, a village near Dorchester in Dorset, formed a Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers. Established as a lodge of the newly formed Grand National Consolidated Trades Union - xxxxxDespite such widespread disapproval, the government stood firm, and George Loveless and his brother James, the prime movers in the forming of the union, together with James Brine, James Hammett, Thomas Stanfield, and his son, John, arrived in Sydney to serve their sentences in August 1834. But the matter did not end there. Protest continued. People across England were outraged not only at the severity of the sentences, but also in the way the case had been manipulated so as to ensure convictions. Eventually a campaign of demonstrations and the sending of petitions to the Home Secretary, Lord John Russell -

xxxxxDespite such widespread disapproval, the government stood firm, and George Loveless and his brother James, the prime movers in the forming of the union, together with James Brine, James Hammett, Thomas Stanfield, and his son, John, arrived in Sydney to serve their sentences in August 1834. But the matter did not end there. Protest continued. People across England were outraged not only at the severity of the sentences, but also in the way the case had been manipulated so as to ensure convictions. Eventually a campaign of demonstrations and the sending of petitions to the Home Secretary, Lord John Russell -

xxxxxThe riots broke out in Kent in June 1830, moved into Surrey and Sussex, and by the end of 1831 had spread across the whole of southern England, including Hampshire, Dorset, Wiltshire, Berkshire and Buckinghamshire. Houses, barns and hay-

xxxxxThe riots broke out in Kent in June 1830, moved into Surrey and Sussex, and by the end of 1831 had spread across the whole of southern England, including Hampshire, Dorset, Wiltshire, Berkshire and Buckinghamshire. Houses, barns and hay-

xxxxx…… A few years after the “Captain Swing” Riots, the introduction of new farming machinery severely reduced the need for manual workers. In 1831 the American inventor Cyrus Hall McCormick (1809-

xxxxx…… A few years after the “Captain Swing” Riots, the introduction of new farming machinery severely reduced the need for manual workers. In 1831 the American inventor Cyrus Hall McCormick (1809-