xxxxxAt the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, Britain was faced with an economic slump, and this brought great hardship for working-

THE LUDDITE RIOTS IN NORTH ENGLAND 1811 -

Acknowledgements

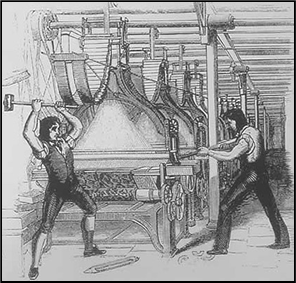

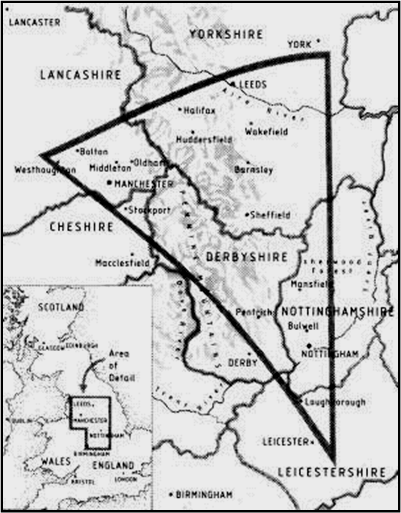

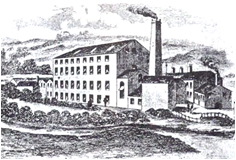

Luddites: 1812 engraving, artist unknown. Map (England): from https://studentmadehistory.wordpress.com. Ludd: 1812 hand coloured etching, artist unknown – Prints and Drawings, British Museum, London. Rawfolds Mill: date and artist unknown.

xxxxxWith the ending of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, Britain -

xxxxxSuch was the severity of this social discontent, that a series of radical riots broke out in 1816 and 1817, including an attack upon the Prince Regent himself. Not surprisingly, this alarmed both central and local government. Harsh legislation and, where necessary, brute force was used to clamp down on any sign of subversion. As we shall see, the inevitable came in 1819 with the so-

xxxxxSuch was the severity of this social discontent, that a series of radical riots broke out in 1816 and 1817, including an attack upon the Prince Regent himself. Not surprisingly, this alarmed both central and local government. Harsh legislation and, where necessary, brute force was used to clamp down on any sign of subversion. As we shall see, the inevitable came in 1819 with the so-

xxxxxBut long before the war was over, the mechanisation of industry was bringing distress in its wake. Not only were the conditions in the factories deplorable -

xxxxxThe movement was particularly well organised and, as a consequence, was thought at one time to have been masterminded by a “General Ludd” or “King Ludd”, though this idea has since been questioned. The men generally operated at night, wearing masks to conceal their identity, and because many -

xxxxxThe movement was particularly well organised and, as a consequence, was thought at one time to have been masterminded by a “General Ludd” or “King Ludd”, though this idea has since been questioned. The men generally operated at night, wearing masks to conceal their identity, and because many -

xxxxxThe government’s reaction was predictably harsh. Some 10,000 troops were drafted into the area, including cavalry and artillery, and virtually given free rein. In London, the Liverpool administration, via its home secretary Viscount Sidmouth, increased the summary powers of magistrates, limited rights of assembly, and suspended the habeas corpus act. At one trial alone, held in York in January 1813, fourteen Luddites were hanged and many were transported to penal colonies, including Australia. And at trials held throughout the area a similar number of sentences was handed out. Faced with such repressive measures the raids became less frequent, and by 1816 the movement had run its course, though, as noted above, it was soon followed by other outbreaks of social disorder.

xxxxxIncidentally, there are a number of versions as to the origin of the name “Luddite”. One is that it comes from a legendary boy called Ludlam who, in a fit of temper, broke his father’s knitting frame. The rioters used his name by signing their proclamations “General Ludd” or “King Ludd” of Sherwood Forest (illustrated). Another is that it comes from a mythical figure known as “Ned Ludd”, a Leicester apprentice who broke up his master’s machine. And a third version is that it comes from a Nottingham saying, based on the Cornish expression “sent all of a lud”, meaning “knocked in a heap”, or smashed. ……

xxxxx…… In February 1812 the English romantic poet Lord Byron, making his maiden speech in the House of Lords, spoke out against the treatment being meted out to the Luddites. Referring to a Commons bill which, among other repressive measures, made the destruction of a machine an offence punishable by hanging, he asked: “Will you erect a gibbet in every field and hang up men like scarecrows? …. Are these the remedies for the starving and desperate?” Their “squalid wretchedness”, he argued, could be compared with the condition of people in “the most oppressed provinces of Turkey”. ……

xxxxx…… Two months later the Luddites in Yorkshire made a raid on Rawfolds Mill near Brighouse. Four of their number were shot dead during the attack, and fourteen were later hanged for their part in the raid. An account of this event featured in Charlotte Bronte’s novel Shirley, published by the Yorkshire-

xxxxx…… After this particular raid, a soldier who had refused to fire on the Luddites was publicly flogged outside the mill itself. For disobeying orders he was sentenced to 300 lashes, but the punishment was stopped after 25, due, it would seem, to the entreaties of William Cartwright, the owner of the mill.

G3c-