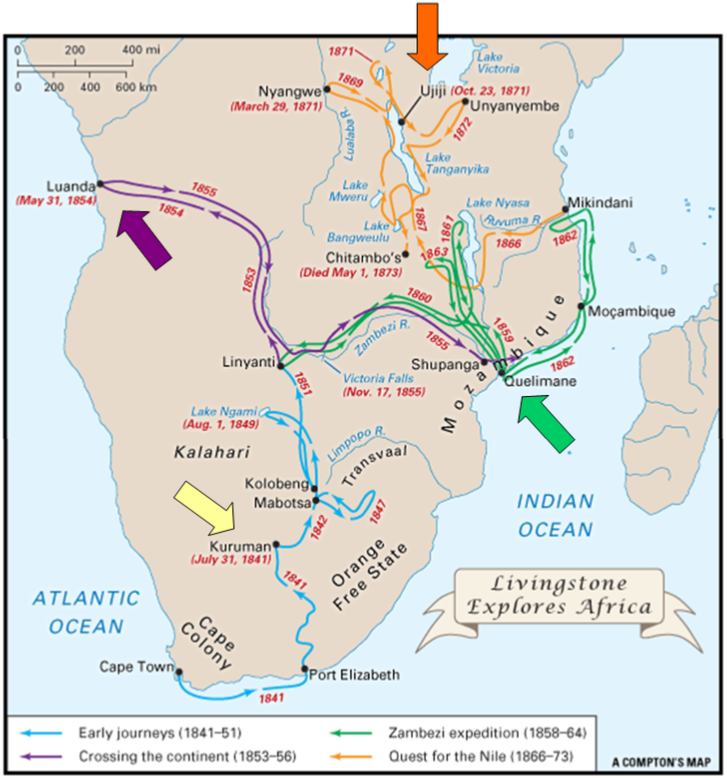

xxxxxThe Scottish

explorer David Livingstone went to southern Africa as a medical

missionary in 1840 and, based at Kuruman in today’s Cape Province,

spent eight years preaching, teaching and tending the sick. To

spread the gospel further, in 1849 he travelled north into

unexplored territory, crossing the Kalahari Desert and discovering

Lake Ngami. In 1853,

after his wife and children had returned to Scotland, he spent

four years penetrating further into the interior. With a small

party of Africans, he first made his way to Luanda, a port on the

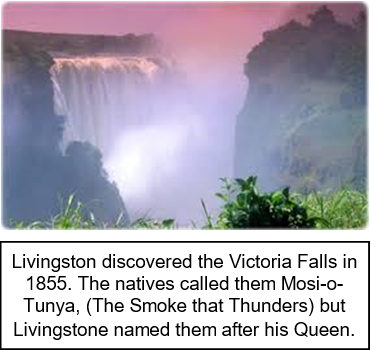

west coast, and then, following the course of the Zambezi, he

reached the Indian Ocean in May 1856, becoming the first European

to see the Victoria Falls and cross the continent from west to

east. On his return to Britain he was welcomed as a national hero.

His Missionary Travels

and Researches in South Africa, plus his extensive

lecture tour, added to his fame, and did much to stimulate

interest in that part of the world. In 1858 he led a government

sponsored expedition into east and central Africa to promote

commerce and civilisation and put an end to the slave trade -

DAVID LIVINGSTONE 1813 -

(G3c, G4, W4, Va, Vb)

Acknowledgements

Livingstone:

after the English portrait painter Frederick Havill (c1815 -

xxxxxThe Scottish missionary and explorer David

Livingston, was born in Blantyre, South Lanarkshire, a town about

12 miles south-

xxxxxThe Scottish missionary and explorer David

Livingston, was born in Blantyre, South Lanarkshire, a town about

12 miles south-

Including:

Paul Belloni du Chaillu

Va-

xxxxxHexarrived at Kuruman (arrowed on map above) in today’s Cape

Province in July 1841, and began preaching, teaching and tending

the sick at a missionary settlement in Bechuanaland (now

Botswana), founded in 1823 by Robert

Moffat (1795-

xxxxxIn 1852 his wife and four children returned to

Scotland, and Livingstone resumed his exploration, determined to

journey even deeper into central Africa or perish in the attempt.

Having been told of a mighty river -

xxxxxIn 1852 his wife and four children returned to

Scotland, and Livingstone resumed his exploration, determined to

journey even deeper into central Africa or perish in the attempt.

Having been told of a mighty river -

xxxxxOn his return to Britain in 1856, news of his extraordinary exploits had preceded him. He was welcomed as a national hero, and acknowledged as an outstanding explorer whose travels required a substantial revision of the contemporary maps of southern and central Africa. In the following year he produced his Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, a work which sold over 70,000 copies in a matter of weeks. And this, together with a lecture tour around Britain and the publication of Dr. Livingstone’s Cambridge Lectures of 1858, added to his fame, and did much to stimulate missionary and commercial work in that part of the world. Indeed, out of such exposure came the setting up of the Universities’ Mission to Central Africa in 1860. Furthermore, these lectures and writings encouraged other explorers to take up the African challenge, including Richard Burton and John Speke in 1858.

xxxxxIn 1858 the

British government, anxious to extend its knowledge of this area,

appointed him British consul for the east coast of Africa, based

at Quelimane (arrowed

on map above, in today’s Mozambique). From here he was required to

lead an expedition to explore east and central Africa “for the

promotion of Commerce and Civilisation and with a view to the

extinction of the slave trade”. (See green

journeys on map above.) This expedition

was on a grand scale compared with his earlier, lone ventures. The

party numbered seventeen, and the seven Europeans included his

wife Mary, his brother Charles, and John Kirk, a Scottish

physician. Supplies were plentiful and a paddle steamer was

provided to make the going much easier -

xxxxxDuring this sponsored expedition Livingstone’s reputation as an explorer suffered something of a setback. Nevertheless on his return to England in 1864, the general public applauded him for his dedication and courage. It was then that, with the assistance of his brother Charles, he wrote his second book, Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi and Its Tributaries, published the following year. Apart from a general account of the expedition, this roundly condemned the slave trade, describing the cruelty and misery inflicted on the local African tribes by the Arab and Portuguese slave traders in the area of Lake Nyasa. It was widely read in government circles and played a significant part in the eventual abolition of this trade.

xxxxxIt was

during his last expedition, begun in 1866 to discover the source

of the Nile (See orange journeys on map above), that

little was heard of his whereabouts and international concern grew

as to his safety. As we shall see, this eventually led to the

sending of a rescue party, led by the Welsh-

xxxxxIncidentally, quite apart from the

demanding and arduous nature of his exploration, Livingstone also

met with open hostility. This came not from the Africans - his

efforts on behalf of the natives. He often had to change his route

to avoid Portuguese settlements, and at one time, in 1852, the

Boers destroyed his home at Kolobeng and attacked Africans who had

joined his mission.

his

efforts on behalf of the natives. He often had to change his route

to avoid Portuguese settlements, and at one time, in 1852, the

Boers destroyed his home at Kolobeng and attacked Africans who had

joined his mission.

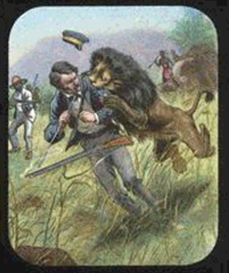

xxxxx…… In 1844 his career in Africa almost came to an abrupt end. He was travelling to Mabotsa, a native settlement some 200 miles north of Kuruman, to set up his own mission station, when he was suddenly attacked by a lion. He was badly mauled by the animal and was lucky to escape with his life. As it was, he was quite seriously injured and lost the full use of his left arm. ……

xxxxx…… Livingstone’s

adventures were not confined to the land. On his return to England

in 1864 he decided to travel via Bombay! He made the journey

across the Indian Ocean -

xxxxx…… In 1863 Livingstone’s eldest son, Robert, was due to join his father in Africa but, having difficulties over the journey, went to the United States instead. He was killed in December of the following year while fighting for the North in the American Civil War. ……

xxxxx…… Duringxhis Zambezi

expedition of 1858-

xxxxxIt was while Livingstone was

making his epic crossing of South Africa that the French-

xxxxxIt was while Livingstone was

making his epic crossing of South Africa that the French-