xxxxxIn his Zoological Philosophy, published in 1809, the French naturalist Jean Baptiste de Lamarck put forward his own theory of evolution, often known as “Lamarckism”. In this he argued that characteristics acquired by organisms in response to their environment were inherited by their offspring -

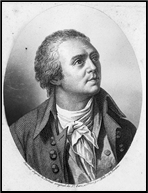

JEAN BAPTISTE DE LAMARCK 1744 -

Acknowledgements

Lamarck: by the French painter Charles Trévenin (1764-

xxxxxThe French naturalist Jean Baptiste de Lamarck devised his own theory of evolution, 50 years before the publication of Charles Darwin's Origin of the Species, and it showed a remarkable insight into this subject. Known as “Lamarckism”, his “transformist” ideas were contained in his Philosophie zoologique (Zoological Philosophy), published in 1809. In this he attempted to show that characteristics or traits which an animal acquires in response to its environment are inherited by its offspring (like the long neck of the giraffe). This hereditary factor was later disproved, but he also advanced the idea that organisms were programmed, as it were, to develop parts that were better adapted to its needs, whilst discarding -

xxxxxThe French naturalist Jean Baptiste de Lamarck devised his own theory of evolution, 50 years before the publication of Charles Darwin's Origin of the Species, and it showed a remarkable insight into this subject. Known as “Lamarckism”, his “transformist” ideas were contained in his Philosophie zoologique (Zoological Philosophy), published in 1809. In this he attempted to show that characteristics or traits which an animal acquires in response to its environment are inherited by its offspring (like the long neck of the giraffe). This hereditary factor was later disproved, but he also advanced the idea that organisms were programmed, as it were, to develop parts that were better adapted to its needs, whilst discarding -

xxxxxLamarck was born in Bazentin-

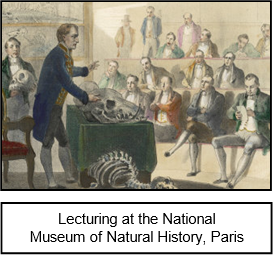

xxxxxWith the outbreak of the Revolution - Lamarck campaigned for a national museum in which collections could be arranged in a “properly systematic order” under specialist supervision. He and others got their way. In 1793 the Museum of Natural History was founded in Paris, replacing the Jardin des Plantes, and he was put in charge of the section on insects and worms. It was hardly the most prestigious of sections, but over the next twenty years or so he virtually made it so. Using the museum’s collection and his own, he put his mind to a more detailed classification of animals. In 1800 he became the first naturalist to make a firm distinction between those which possessed a backbone (a bony spinal column) -

Lamarck campaigned for a national museum in which collections could be arranged in a “properly systematic order” under specialist supervision. He and others got their way. In 1793 the Museum of Natural History was founded in Paris, replacing the Jardin des Plantes, and he was put in charge of the section on insects and worms. It was hardly the most prestigious of sections, but over the next twenty years or so he virtually made it so. Using the museum’s collection and his own, he put his mind to a more detailed classification of animals. In 1800 he became the first naturalist to make a firm distinction between those which possessed a backbone (a bony spinal column) -

xxxxxHis other works included Illustrations of Species in 1785, Dictionary of Botany, a work in four volumes first produced in 1796, and Hydrogéologie, a history of the earth which was published in1802 but aroused little interest. He retired from his post at the Museum of Natural History in 1818, and by that time his sight was beginning to fail. He spent the last few years of his life totally blind, cared for by his devoted daughters. In his own time, it must be said, Lamarck’s work was virtually neglected. He never received the recognition and esteem accorded his patron Buffon nor his colleague Cuvier, and much of his life was a struggle against poverty. In the end he received a poor man’s burial and died in obscurity. Yet, in the course of time, his ideas on hereditary, whilst speculative and partially flawed, did make an important contribution to the theory of evolution, if only by the interest they stimulated in this subject. In addition, his biological classification, particularly concerning invertebrates, has remained of substantial value down to this day.

xxxxxHis other works included Illustrations of Species in 1785, Dictionary of Botany, a work in four volumes first produced in 1796, and Hydrogéologie, a history of the earth which was published in1802 but aroused little interest. He retired from his post at the Museum of Natural History in 1818, and by that time his sight was beginning to fail. He spent the last few years of his life totally blind, cared for by his devoted daughters. In his own time, it must be said, Lamarck’s work was virtually neglected. He never received the recognition and esteem accorded his patron Buffon nor his colleague Cuvier, and much of his life was a struggle against poverty. In the end he received a poor man’s burial and died in obscurity. Yet, in the course of time, his ideas on hereditary, whilst speculative and partially flawed, did make an important contribution to the theory of evolution, if only by the interest they stimulated in this subject. In addition, his biological classification, particularly concerning invertebrates, has remained of substantial value down to this day.

xxxxxIncidentally, Lamarck coined the word botany to cover the science of plants, and introduced the terms “vertebrate” and “invertebrate”. He also popularised the word biology, but this word was first used in 1802 by the German naturalist and physician Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus (1776-

xxxxx…… Lamarckxwas succeeded as professor of zoology at the Museum of Natural History by Pierre-

xxxxx…… Laterxin the century the American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope (1840-

Including:

Georges Cuvier,

Louis Agassiz, and

Nicolas Théodore

de Saussure

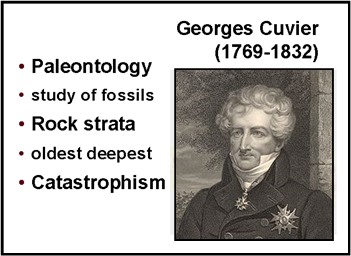

xxxxxThe French naturalist and anatomist Georges Cuvier opposed Lamarck’s theory on evolution. He believed that all animals had been created as individual, immutable species at the time of Creation and that, as evidenced by his discovery of fossils, some had become extinct at various but defined periods of time. Holding to the current belief that the earth had only been formed some six thousand years ago, he explained these fossils away by the doctrine of catastrophism -

xxxxxThe French naturalist and anatomist Georges Cuvier opposed Lamarck’s theory on evolution. He believed that all animals had been created as individual, immutable species at the time of Creation and that, as evidenced by his discovery of fossils, some had become extinct at various but defined periods of time. Holding to the current belief that the earth had only been formed some six thousand years ago, he explained these fossils away by the doctrine of catastrophism -

xxxxxThis doctrine was soon to be disproved, but In carrying out this detailed study of fossils, he made the first classification of fossils, and he also reconstructed whole skeletons of large extinct vertebrates. He noted, too, that the deeper strata contained the remains of animals that differed substantially in shape and size from earlier fossils and creatures living at the time. His findings and observations on this aspect of his work were expounded in his Researches on the Fossil Bones of Quadrupeds, published in 1812, and his Discourse on the Revolutions of the Globe of 1825.

xxxxxCuvier was born at Montbeliard, then in the Duchy of Wurttemberg and, after studying natural history at Stuttgart Academy, worked for about seven years as a tutor to a noble family in Normandy. During this period he spent much time in studying and writing on marine invertebrates, and in 1795 this research earned him a place on the staff of the Museum of Natural History in Paris, working alongside the professor of zoology Étienne Geoffroy Saint-

xxxxxCuvier was born at Montbeliard, then in the Duchy of Wurttemberg and, after studying natural history at Stuttgart Academy, worked for about seven years as a tutor to a noble family in Normandy. During this period he spent much time in studying and writing on marine invertebrates, and in 1795 this research earned him a place on the staff of the Museum of Natural History in Paris, working alongside the professor of zoology Étienne Geoffroy Saint-

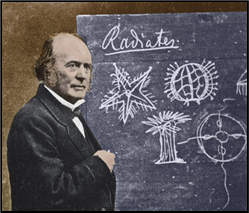

xxxxxIt was in 1798 that Cuvier drew up his "Elementary Survey of the Natural History of Animals", a work in which he outlined his own method of classifying the entire animal kingdom, and he expanded this two years later, dividing all animals into four large categories based on broad anatomical similarities: Articulates, Radiatas, Vertebrates and Mollusks. His Lessons on Comparative Anatomy, written with the assistance of other naturalists, was a compendium of knowledge on the subject, published over five years (1800 to 1805), and his major work The Animal Kingdom, begun in 1817 and made up of nine volumes, contained the considerable amount of knowledge he had accumulated on the structure of extant and fossil animals. Ironically enough, some of his findings were later used in support of Darwin’s theory of evolution.

xxxxxIt was in 1798 that Cuvier drew up his "Elementary Survey of the Natural History of Animals", a work in which he outlined his own method of classifying the entire animal kingdom, and he expanded this two years later, dividing all animals into four large categories based on broad anatomical similarities: Articulates, Radiatas, Vertebrates and Mollusks. His Lessons on Comparative Anatomy, written with the assistance of other naturalists, was a compendium of knowledge on the subject, published over five years (1800 to 1805), and his major work The Animal Kingdom, begun in 1817 and made up of nine volumes, contained the considerable amount of knowledge he had accumulated on the structure of extant and fossil animals. Ironically enough, some of his findings were later used in support of Darwin’s theory of evolution.

xxxxxApart from his research at the museum, he also interested himself in the development of scientific knowledge as a whole, producing an Historical Report on the Progress of the Sciences in 1810, and for many years he took an active part in furthering public education, and setting up more provincial universities.

xxxxxCuvier was a pioneer and the founder, indeed, of comparative anatomy, a discipline which studies the physical similarities among the diverse members of the animal kingdom. It is primarily a study of adult vertebrates but, as Cuvier clearly demonstrated, it can also include evidence from fossil records. His research in this respect can hardly be exaggerated. He not only classified fossils and involved them in zoological research, but he also related them to rock strata and opened up the whole question of evolution through time. Such pioneer work made him the founder of vertebrate palaeontology. His triumph in this field was the identification and the naming of the pterodactyl, a large flying creature that existed some 200 million years ago. However, his non-

xxxxxIncidentally, the need for an accurate classification of living creatures was clearly demonstrated in 1799 when the production of an encyclopedia was being discussed at a meeting of the French Academy. A member suggested that a crab could be defined as “a small red fish that walks backwards”. Cuvier was obliged to point out that a crab was not a fish, was not always red in colour, and did not walk backwards! ……

xxxxxIncidentally, the need for an accurate classification of living creatures was clearly demonstrated in 1799 when the production of an encyclopedia was being discussed at a meeting of the French Academy. A member suggested that a crab could be defined as “a small red fish that walks backwards”. Cuvier was obliged to point out that a crab was not a fish, was not always red in colour, and did not walk backwards! ……

xxxxx…… Cuvier’ investigations were greatly assisted by the work of his fellow countryman Antoine Laurent de Jussieu (1748-

xxxxxThe French anatomist Georges Cuvier (1769-

G3c-

xxxxxA man who knew Georges Cuvier well was the Swiss zoologist and geologist Louis Agassiz (1807-

xxxxxA man who knew Cuvier well and worked with him in the early 1830s was the Swiss zoologist and geologist Louis Agassiz (1807-

xxxxxA man who knew Cuvier well and worked with him in the early 1830s was the Swiss zoologist and geologist Louis Agassiz (1807-

xxxxxA change of profession came about in 1836, doubtless under Humboldt’s influence. In that year he went on a tour of glaciers in the Chamonix district of Mont Blanc, and became convinced that the large boulders that were scattered across the plains of northern Europe had been deposited by the movement of glaciers. He carried out some experiments and deduced from these that at one time, during what he described as a “Great Ice Age”, most of the northern region of the earth had been covered in vast sheets of ice. There followed in 1840 his A Study of Glaciers, the first book on the study of glaciers (glaciology) and their geological effects (glacial geomorphology), and the first to introduce the controversial idea of an historic ice age.

xxxxxOn the strength of his new findings, he went on a lecture tour of the United States in 1846, starting at Boston, and, because of the enthusiastic reception he received, decided to make his home there. He became an American citizen, and in 1848 was appointed professor of zoology and geology at Harvard University.

xxxxxIn 1865 he led an expedition to Brazil, during which 80,000 fish specimens were collected from the Amazon, and also visited the region around Lake Superior. His last research was making a study of viviparous fish (fish that give birth to live young), found in the surf along Californian beaches. In 1855 he began a ten volume work on Contributions to the Natural History of the United States -

xxxxxIn 1865 he led an expedition to Brazil, during which 80,000 fish specimens were collected from the Amazon, and also visited the region around Lake Superior. His last research was making a study of viviparous fish (fish that give birth to live young), found in the surf along Californian beaches. In 1855 he began a ten volume work on Contributions to the Natural History of the United States -

xxxxxBy his research he became, in his time, the foremost authority on fossil and living fish, but today he is mainly remembered on two accounts: his theory that the earth was once subjected to an extensive ice age, and for his outspoken opposition to Darwin’s theory of evolution.

xxxxxIncidentally, in 1879 the remains of a vast ancient glacial lake that once covered North Dakota, Minnesota and Manitoba was named Agassiz in recognition of his prominent role in the development of the glacial theory. ……

xxxxx…… Agassiz numbered among his many friends the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He wrote a poem to mark the scientist’s fiftieth birthday. ……

xxxxx…… Agassiz died in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his grave in Mount Auburn Cemetery is marked by a boulder taken from the Aar glacier, near to the spot where he carried out his first experiments. The pine trees that shelter his grave were taken from his childhood home in Môtier.

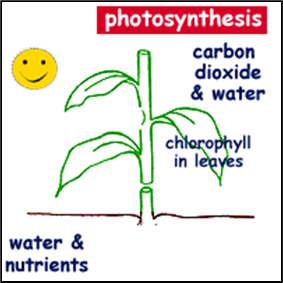

xxxxxA noted botanist and plant physiologist at this time was the Swiss chemist Nicolas Théodore de Saussure (1767-

xxxxxA noted botanist and plant physiologist at this time was the Swiss chemist Nicholas Théodore de Saussure (1767-

xxxxxA noted botanist and plant physiologist at this time was the Swiss chemist Nicholas Théodore de Saussure (1767-

xxxxxIt was during these alpine expeditions that he became interested in botany, especially in the study of plant physiology. In 1797 he published three articles on the formation of carbonic acid in plant tissues, but his most important contribution came in 1804, when he confirmed that during photosynthesis plants gain weight by absorbing carbon dioxide and also water, a vital ingredient in the process. He  then went on to demonstrate the need for plants to absorb nitrogen from the soil.

then went on to demonstrate the need for plants to absorb nitrogen from the soil.

xxxxxSaussure was born in Geneva, and, for the most part, was educated by his father. In 1802 he was appointed professor of geology and mineralogy at the city’s university, but he continued with his experiments in botany and his Recherches chimiques sur la végétation (Chemical Research on Vegetation), published in 1804, laid the foundation of phytochemistry -