IMMANUEL KANT 1724 -

(G1, G2, G3a, G3b, G3c)

xxxxxThe revolutionary theories of the brilliant German philosopher Immanuel Kant are basically found in his three Critiques, his Critique of Pure Reason of 1781, his Critique of Practical Reason, published in 1788, and his Critique of Judgment, produced in 1790. In attempting to explain the formation of knowledge, he breaks new ground by arguing that the mind, far from being a sponge which just soaks up the experience of the senses, has an important part to play. It was, in fact, a conceptual apparatus which shapes our understanding of the world based on the sense experiences it receives. However, there was a possible difference between the world we see and the world as it really is, and he calls the first phenomenon (what is seen) and the second noumenon (that which cannot be known). In metaphysics, concepts like God and freedom cannot be explained because they are outside the experience of sensation, but a moral, universal law could be established (the categorical imperative) based on a sense of duty dictated by reason. This was achieved when people acted in the same way as they would want everyone else to act. Such theories drove philosophy in a new direction, and made Kant the starting point of modern philosophical thought. Apart from his Critiques, Kant produced a vast series of books and articles across a wide range of subjects, including works on the formation of the universe and physical geography.

xxxxxAs noted earlier, the brilliant German philosopher Immanuel Kant published his Critique of Pure Reason in 1781 (G3a), a work which began a revolution in philosophical thought. This and his two other Critiques, his Critique of Practical Reason, published in 1788, and his Critique of Judgment of 1790, closely examined the three important realms of philosophy -

xxxxxAs noted earlier, the brilliant German philosopher Immanuel Kant published his Critique of Pure Reason in 1781 (G3a), a work which began a revolution in philosophical thought. This and his two other Critiques, his Critique of Practical Reason, published in 1788, and his Critique of Judgment of 1790, closely examined the three important realms of philosophy -

xxxxxIn the first instance, his Critique of Pure Reason of 1781 contained the keystone of his radical philosophical thought. In it, Kant made only limited use of earlier attempts to explain the formation of knowledge, theories based, for the most part, on the rationalism of the French philosopher René Descartes and the empiricism of the English scientist Francis Bacon. Instead he examined for the first time the part played by the mind in forming our understanding of the world around us. The senses, he argued, were based on experience (a posteriori or empirical judgment), but knowledge was dependent on the mind (a priori judgment). In this concept, he maintained that the mind was not just a “passive” piece of wax which became imprinted, as it were, by external sensations, but a conceptual apparatus which shaped our understanding of the world even though divorced from experience itself. Thus experience by the senses provided the material, whilst the mind provided the structure by which this material was arranged, understood and given meaning.

xxxxxKant then went further and divided this contribution of the mind into what he called “categories”, the means by which the material experienced is structured, be it in broad divisions, like quantity and quality, or specific areas, such as time and space. But, this said, Kant is at pains to point out that knowledge so acquired could never be verified as such because it was based on how things are seen by us. There was a likely difference, however, between the world as it appears to us, and the world as it actually is. From this stems his distinction between what he called noumenon (that which cannot be known), and the phenomenon, things as they appear to be.

xxxxxIt followed that whilst a priori judgments were feasible in subjects like mathematics and physics, they were not and could not be valid in metaphysics. Concepts like freedom, immortality and God, for example, were outside space and time, and could only be regarded “as if” they were true. Therefore, as moral law cannot be sanctioned by reason, it can only be obeyed for its own sake. Thus Kant’s stand on ethics is based on a sense of duty dictated by reason, not on feelings, inclinations, or a blind obedience to law or custom. People, he argued, should act in the same way as they would want everyone else to act. If that course of action were followed, then it became, in his terminology, a “categorical imperative”, a form of judgment that has a universal validity.

xxxxxThis idea of a person pursuing good out of a sense of duty testifies to Kant’s basic belief in the freedom of the individual and, more importantly, in the desire of that individual to obey universal laws based on reason. Optimistically, he saw the world moving towards an ideal society in which reason would “bind every law giver to make his laws in such a way that they could have sprung from the united will of an entire people". Indeed, in 1795, towards the end of his life, he wrote a treatise entitled Perpetual Peace in which he advocated the establishment of a world federation made up of republican states.

xxxxxAs early as the 1760s Kant was critical of the theories and methodology of the German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz. He was particularly critical of his concept of Being, arguing that it was not possible to prove the existence of God by thought alone because this concept was not and never could be an object of experience. And in another work of this time, Enquiry into the Proofs for the Existence of God (1763), he dismissed the efforts made by Descartes to prove human existence simply by logic. Nevertheless, Kant did believe in the existence of a God, and in an after-

xxxxxAnd it was in these early years that Kant showed a marked interest in scientific matters, influenced to a large extent by the writings of the English scientist Isaac Newton. In his Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens, produced in 1755, he put forward the idea that the Universe was made up of a large number of galaxies, and that the solar system was part of one of these vast clusters. He later went on to suggest that the universe had been formed out of a spinning nebula, a hypothesis that was developed later by the French astronomer Pierre-

xxxxxKant was born in Konigsberg, East Prussia, now Kaliningrad in Russia. After attending the local Latin school from the age of 8, he studied mathematics and physics at the city’s university (though he was actually enrolled as a theological student). Following the death of his father in 1746, he was obliged to work as a family tutor for some nine years, but returned to his studies in 1755 and, on their completion, joined the staff as a lecturer. It was here that he soon gained a reputation for the quality of his teaching, and the width of his subject matter, which included topics of scientific interest and a course in physical geography. A humorous and inspiring lecturer, in 1770 he was appointed professor of logic and metaphysics, a post he held for almost 30 years. To this period belongs his three famous Critiques and a series of works in which he elaborated upon his philosophy. (This print of Konigsberg castle shows Kant’s house on the left).

xxxxxKant was born in Konigsberg, East Prussia, now Kaliningrad in Russia. After attending the local Latin school from the age of 8, he studied mathematics and physics at the city’s university (though he was actually enrolled as a theological student). Following the death of his father in 1746, he was obliged to work as a family tutor for some nine years, but returned to his studies in 1755 and, on their completion, joined the staff as a lecturer. It was here that he soon gained a reputation for the quality of his teaching, and the width of his subject matter, which included topics of scientific interest and a course in physical geography. A humorous and inspiring lecturer, in 1770 he was appointed professor of logic and metaphysics, a post he held for almost 30 years. To this period belongs his three famous Critiques and a series of works in which he elaborated upon his philosophy. (This print of Konigsberg castle shows Kant’s house on the left).

xxxxxIn the 1790s his health began to fail. A man of small stature -

xxxxxKant, the greatest of modern philosophers, considered that his radical re-

xxxxxIncidentally, apart from a brief visit to the town of Arnsdorf, some 60 miles away, Kant never left Konigsberg. As regular as clockwork he took his daily walk in his native city, along a route which came to be known as “The Philosopher’s Walk”. ……

xxxxxIncidentally, apart from a brief visit to the town of Arnsdorf, some 60 miles away, Kant never left Konigsberg. As regular as clockwork he took his daily walk in his native city, along a route which came to be known as “The Philosopher’s Walk”. ……

xxxxx…… We are told that the German poet and novelist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe once said that reading the works of Kant was like entering a lighted room. Not everyone would share that view on first reading! Kant himself was concerned about the clarity of his written thoughts and, in the case of his Critique of Pure Reason, for example, wrote the Prolegomena in 1783, and a second edition of the Critique in 1787, in an attempt to make his meaning less obscure. His writing does tend to be full of technical jargon, and, at first reading, this makes it difficult to fathom out his meaning in some cases, and close to impossible in a few others. For instance, Kant explains the causes of laughter as “the sudden transformation of a tense expectation into nothing”.

Acknowledgements

Kant: 18th century, artist unknown – private collection. Konigsburg: engraving, date and artist unknown. Daily Walk: etching, date and artist unknown. Fichte: engraving by the German artist Johann Friedrich Jugel (1772-

Including:

Johann Gottlieb Fichte

and William Paley

xxxxxThe German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-

xxxxxThe German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762- ) was a great admirer of Immanuel Kant. He was born at Rammenau in Upper Lusatia, Saxony, and it was after studying at the universities of Jena and Leipzig, and working as a private tutor in Zurichm, that he became interested in Kantian philosophy. It was in the early 1790s that he wrote his essay entitled An Attempt at a Critique of All Revelation, a work in which he developed Kant’s justification of faith. He visited the great master in 1791, and gained approval for this work, but when it was published in 1792 his name was omitted from the cover and the work was thought to be by Kant himself. However, the omission proved to be no bad thing for Fichte. When the work was republished, accredited to Fichte, and praised by Kant, the young philosopher took on something of his master’s mantle!

) was a great admirer of Immanuel Kant. He was born at Rammenau in Upper Lusatia, Saxony, and it was after studying at the universities of Jena and Leipzig, and working as a private tutor in Zurichm, that he became interested in Kantian philosophy. It was in the early 1790s that he wrote his essay entitled An Attempt at a Critique of All Revelation, a work in which he developed Kant’s justification of faith. He visited the great master in 1791, and gained approval for this work, but when it was published in 1792 his name was omitted from the cover and the work was thought to be by Kant himself. However, the omission proved to be no bad thing for Fichte. When the work was republished, accredited to Fichte, and praised by Kant, the young philosopher took on something of his master’s mantle!

xxxxxOn the strength of this work (and a little help from his fellow countryman the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe), he was appointed professor of philosophy at Jena University in 1793, but six years later, following charges of atheism, he was forced to leave. He went to Berlin, and in 1809 became a professor at the new university there. It was while at Jena that he produced his major philosophical treatise the Wissenschaftslehre (The Science of Knowledge), a work in which he questioned some aspect of Kant’s teaching. Soon after arriving in Berlin, he reaffirmed his views in Die Bestimmung des Menschen (The Vocation of Man), published in 1800, but from then onwards he devoted much of his time to public affairs and delivering lectures. To this period belongs his Reden an die deutsche (Addresses to the German People) -

xxxxxOn the strength of this work (and a little help from his fellow countryman the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe), he was appointed professor of philosophy at Jena University in 1793, but six years later, following charges of atheism, he was forced to leave. He went to Berlin, and in 1809 became a professor at the new university there. It was while at Jena that he produced his major philosophical treatise the Wissenschaftslehre (The Science of Knowledge), a work in which he questioned some aspect of Kant’s teaching. Soon after arriving in Berlin, he reaffirmed his views in Die Bestimmung des Menschen (The Vocation of Man), published in 1800, but from then onwards he devoted much of his time to public affairs and delivering lectures. To this period belongs his Reden an die deutsche (Addresses to the German People) -

xxxxxIn much of his work, Fitchte supported or expanded the ideas of his master, but he also developed a distinctive, idealistic philosophy of his own. Above all, he regarded as unsatisfactory Kant’s conception of noumenon (that which cannot be known), based on the theory that there was a difference between the world as it appears to us and the world as it actually is. This, he argued, denied man’s knowledge of objective truth. He thus placed at the centre of his philosophy a creative Ego as the ultimate source of reality. As its role was ethical, this universal and absolute Pure Ego came to be identified as a God which brought about all change and understood all things. This was the source of experience from which all forms of knowledge could be deduced by means of subjective contemplation.

xxxxxBut Ficthe was also concerned with the importance of “practical” philosophy as it affected the well being and advancement of the state. On similar lines to Kant, he argued that if everyone were fully developed morally there would be no need for a state. However, given the freedom of the individual, the duties and rights of the state were clearly necessary to ensure moral and social progress, and the eventual attainment of what should be. Failure to achieve this end was due, he maintained, to the failure of the country’s education system. This should adopt the teaching methods put forward by the Swiss educational reformer Johann Pestalozzi, but organized completely by the state. Children could then be educated in separate communities until such time as their parents had come to recognize the duties expected of them.

xxxxxFichte had shown his political colours when, in 1793, he came out strongly in favour of the French Revolution. He applauded their struggle for liberty, arguing that every nation needed a time for reform and amendment. This stance marked him out as a dangerous democrat, but in the early 1800s he was hailed as a patriot. Napoleon having humiliated the Germans on the battlefield and occupied Berlin, his Reden an die deutsche Nation (Addresses to the German Nation) did much to develop German nationalism. Delivered in Berlin in 1807 and 1808, they called for the political union of the German states, so that France could be defeated, and Germany could take her rightful place as the leading power on the continent. It was stirring stuff and went down well.

xxxxxFichte had shown his political colours when, in 1793, he came out strongly in favour of the French Revolution. He applauded their struggle for liberty, arguing that every nation needed a time for reform and amendment. This stance marked him out as a dangerous democrat, but in the early 1800s he was hailed as a patriot. Napoleon having humiliated the Germans on the battlefield and occupied Berlin, his Reden an die deutsche Nation (Addresses to the German Nation) did much to develop German nationalism. Delivered in Berlin in 1807 and 1808, they called for the political union of the German states, so that France could be defeated, and Germany could take her rightful place as the leading power on the continent. It was stirring stuff and went down well.

xxxxxThe concept of the state advanced by Fichte, and his optimistic view of society in the long term, had a direct influence upon his fellow countrymen, the philosophers Friedrich Wilhelm von Schelling and G.W.F. Hegel, but his lasting influence was undoubtedly his contribution to the German nation as a patriot and liberal. His jingoism not only served the needs of his day, but was also a spur to German nationalism throughout the 19th century.

xxxxxIncidentally, during his stay in Berlin from 1799 to 1806, Fichte numbered among his friends the German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-

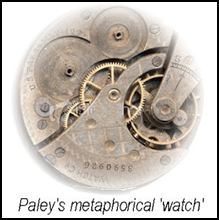

xxxxxIt was at this time that the English theologian and philosopher William Paley (1743-

xxxxxIt was around this time, in 1794, that the English theologian and philosopher William Paley (1743-

xxxxxIt was around this time, in 1794, that the English theologian and philosopher William Paley (1743-

xxxxxPaley was born in Peterborough, England, and educated at Christ’s College, Cambridge. He was ordained in 1767, and held a number of senior appointments in the Anglican Church, including Archdeacon of Carlisle in 1782 and a Canon of St. Paul’s, London, in 1794. His ethical theory in support of Utilitarianism -

G3b-