QUEEN VICTORIA’S GOLDEN JUBILEE 1887 (Vc)

Acknowledgements

Banquet: by the

English artist Robert Taylor Pritchett (1828-

xxxxxThe event was

marked by a royal banquet at Buckingham Palace, attended by fifty

foreign kings and princes, and all the heads of the British

Empire’s dominions and colonies. The following day the queen

travelled in an open landau to Westminster Abbey -

Vc-

xxxxxBut not

everyone shared in the rejoicing. In Ireland -

xxxxxAndxthe event

also brought in its wake an unexpected and embarrassing consequence.

As part of the Jubilee festivities, two Indian servants were

appointed as waiters at the Queen’s table, and this trivial matter,

as it so happened, was to bring about a serious crisis within the

royal household.

xxxxxAndxthe event

also brought in its wake an unexpected and embarrassing consequence.

As part of the Jubilee festivities, two Indian servants were

appointed as waiters at the Queen’s table, and this trivial matter,

as it so happened, was to bring about a serious crisis within the

royal household.

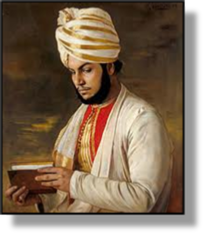

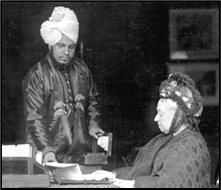

xxxxxReminiscent of her scandalous relationship with her Scottish manservant John Brown some years earlier, Victoria now fell under the spell of one of them, a young handsome Muslim named Abdul Karim (illustrated). Within a short time he had became her constant companion, assisting her in her daily duties and teaching her Hindustani. The Queen sent him notes signed “your loving mother”, and within two years had appointed him her “Indian Secretary” (her “Munshi” in urdu), with a cottage provided in the royal grounds. This indiscreet affection and devotion for one whom many regarded as an ambitious young imposter caused consternation among the royal household. Certain senior figures attempted to discredit him and have him removed, and a number of members threatened to resign.

xxxxxMatters came to a head in the year of the

Queen’s Diamond Jubilee when, to everyone’s disbelief, she declared

that she wished to bestow a knighthood on her loyal Indian servant.

When this was opposed, she even threatened to pull out of the

programme of celebrations. Only a threat by the Prince of Wales to

have her declared insane brought her to her senses, though Karim

remained at her side throughout the Diamond Jubilee events. When

Victoria died in 1901 Karim was dismissed and sent back to India -

xxxxxMatters came to a head in the year of the

Queen’s Diamond Jubilee when, to everyone’s disbelief, she declared

that she wished to bestow a knighthood on her loyal Indian servant.

When this was opposed, she even threatened to pull out of the

programme of celebrations. Only a threat by the Prince of Wales to

have her declared insane brought her to her senses, though Karim

remained at her side throughout the Diamond Jubilee events. When

Victoria died in 1901 Karim was dismissed and sent back to India -