xxxxxThe English man of letters Samuel Johnson dominated the London literary scene during the latter part of the 18th century. He is remembered above all for his famous Dictionary, published in 1755 and containing 40,000 entries. He first wrote for the Gentleman's Magazine -

SAMUEL JOHNSON 1709 -

Acknowledgements

Johnson: detail, by the English painter Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-

G2-

xxxxxThe larger-

xxxxxThe larger-

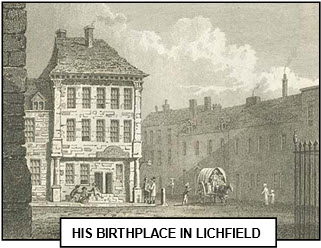

xxxxxA brilliant conversationalist, writer and critic, Johnson was born in Lichfield, Staffordshire, the son of a bookseller. He only went to the local school, but he read widely in his own time. When he went up to Pembroke College, Oxford, in 1717, he impressed his tutor with his knowledge of Latin poetry, but he was forced to leave early through lack of funds. It was at this time that he suffered the first of two serious bouts of depression, an experience which left him with a strong religious faith. In 1735, he married Elizabeth Porter, an attractive and intelligent widow about 20 years his senior, and this brought a measure of comfort and stability to his life, as well as providing money for the opening of a school at Edial, near Lichfield. Unfortunately, this only attracted three pupils, so in 1737 he abandoned teaching and, accompanied by his wife and David Garrick (one of the three pupils), he journeyed to London with -

xxxxxA brilliant conversationalist, writer and critic, Johnson was born in Lichfield, Staffordshire, the son of a bookseller. He only went to the local school, but he read widely in his own time. When he went up to Pembroke College, Oxford, in 1717, he impressed his tutor with his knowledge of Latin poetry, but he was forced to leave early through lack of funds. It was at this time that he suffered the first of two serious bouts of depression, an experience which left him with a strong religious faith. In 1735, he married Elizabeth Porter, an attractive and intelligent widow about 20 years his senior, and this brought a measure of comfort and stability to his life, as well as providing money for the opening of a school at Edial, near Lichfield. Unfortunately, this only attracted three pupils, so in 1737 he abandoned teaching and, accompanied by his wife and David Garrick (one of the three pupils), he journeyed to London with -

xxxxxThere, in the heart of the city that he came to love so much, he managed to eke out a living, mainly by contributing essays, poetry and articles to the Gentleman's Magazine. His contributions, churned out on a wide range of subjects, included a series of speeches purporting to come from debates being held in the House of Commons. Satirically called Debates in the Senate of Magna Lilleputia, they were based purely on hear-

xxxxxThere, in the heart of the city that he came to love so much, he managed to eke out a living, mainly by contributing essays, poetry and articles to the Gentleman's Magazine. His contributions, churned out on a wide range of subjects, included a series of speeches purporting to come from debates being held in the House of Commons. Satirically called Debates in the Senate of Magna Lilleputia, they were based purely on hear-

xxxxxThen in 1750 he founded his own periodical, The Rambler, and followed this up with The Idler, published in a weekly newspaper from 1758, and written in a somewhat lighter vein. Through these periodicals he produced novels, biographies, and a large number of brilliant essays on current affairs, literature and literary criticism, the majority aimed to "inculcate wisdom and piety". These periodicals, and his individual writings, were well received and earned him a reputation as an astute observer of human nature, but they were not sufficient to solve his financial problems in full. When his mother died in 1759, for example, he was obliged to put pen rapidly to paper to pay off her debts and the funeral expenses. The result was his long work of fiction Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia, a piece of romance prose about a young man who sets out to fulfil his daydreams and ends up disappointed and disillusioned. It sold quite well, but in the same year he was obliged to move from his house in Gough Square, behind Fleet Street, (now a Johnson museum), to find cheaper accommodation.

xxxxxThen in 1750 he founded his own periodical, The Rambler, and followed this up with The Idler, published in a weekly newspaper from 1758, and written in a somewhat lighter vein. Through these periodicals he produced novels, biographies, and a large number of brilliant essays on current affairs, literature and literary criticism, the majority aimed to "inculcate wisdom and piety". These periodicals, and his individual writings, were well received and earned him a reputation as an astute observer of human nature, but they were not sufficient to solve his financial problems in full. When his mother died in 1759, for example, he was obliged to put pen rapidly to paper to pay off her debts and the funeral expenses. The result was his long work of fiction Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia, a piece of romance prose about a young man who sets out to fulfil his daydreams and ends up disappointed and disillusioned. It sold quite well, but in the same year he was obliged to move from his house in Gough Square, behind Fleet Street, (now a Johnson museum), to find cheaper accommodation.

xxxxxThe turning point in his career came in 1747 -

xxxxxThe turning point in his career came in 1747 -

xxxxxAs we shall see (1773 G3a), the next twenty years were to witness the founding of his famous Literary Club -

xxxxxIncidentally, in his own words, Johnson was born "almost dead". He contracted scrofula (a disease of the lymphatic glands) soon after birth, and at the age of two and a half years was taken to London to be touched by Queen Anne -

xxxxxA good illustration of Johnson's brilliant command of the English language, and his extraordinary powers of invective, can be seen when he was working on his Dictionary. It appears that Lord Chesterfield (1694-

Including:

Lord Chesterfield

xxxxxAnd to bang home his point, part of his definition of the word "patron" reads: Commonly, a wretch who supports with insolence, and is paid with flattery.

xxxxxFurthermore, this was the same Lord Chesterfield who gained a literary reputation for his witty and charming Letters to his Son on the Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman (followed later by letters to his godson). Written from 1737 to 1768, they aimed at showing how a gentleman should behave in society, but Johnson dismissed the letters as "teaching the morals of a whore and the manners of a dancing master". Nor, it would seem, did the letters bear fruit. His son was later described as a "lout" and, in the opinion of the writer Fanny Burney, his godson showed few signs of breeding.

xxxxxFurthermore, this was the same Lord Chesterfield who gained a literary reputation for his witty and charming Letters to his Son on the Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman (followed later by letters to his godson). Written from 1737 to 1768, they aimed at showing how a gentleman should behave in society, but Johnson dismissed the letters as "teaching the morals of a whore and the manners of a dancing master". Nor, it would seem, did the letters bear fruit. His son was later described as a "lout" and, in the opinion of the writer Fanny Burney, his godson showed few signs of breeding.

xxxxxIs not a patron, my Lord, one who looks with unconcern on a man struggling for life in the water, and, when he has reached ground, encumbers him with help. The notice which you have been pleased to take of my labours, had it been early, had been kind; but it has been delayed till I am indifferent and cannot enjoy it, till I am solitary and cannot impart it, till I am known, and do not want it.