xxxxxAs we have

seen, the British suffered a humiliating defeat in the First

Anglo-Boer War of 1881, allowing the Boers to regain control of the

Transvaal. The opportunity for revenge came with the discovery of

vast gold deposits south of Johannesburg in 1886. This led to a

large influx of fortune seekers, and these Uitlanders (foreigners

or outsiders) posed a threat to the Boer government. Restrictions

were imposed on their right to vote and take up permanent

residence, but this only exacerbated the situation. In 1895 the

foreign workers in Johannesburg planned a resurrection and Cecil

Rhodes, then president of the Cape Colony, planned an attack in

support of them in order to bring about the overthrow of the

Transvaal government. He figured that Britain could then take

control of the country, together with the Orange Free State, and

his own gold mining company could benefit from the new finds. But

the “Jameson Raid”, led by Rhodes’ right-hand man Leander

Starr Jameson, was launched prematurely. The small army was

harassed by the Boers and finally forced to surrender at Doornkop,

some twenty miles short of Johannesburg, early in January 1896. In Britain this aroused

strong antagonism towards the Boers and towards the German Kaiser,

Wilhelm II, who congratulated the Transvaal government on their

success. Eventually, after a number of failed attempts to persuade

the Boers to give equality to British subjects in the Transvaal,

the British government - clearly determined to regain control

over this lucrative area - made unacceptable demands upon the

Transvaal president, Paul Kruger, and the Second Anglo-Boer

War broke out in October 1899.

THE JAMESON RAID 1895 /

1896 (Vc)

Acknowledgements

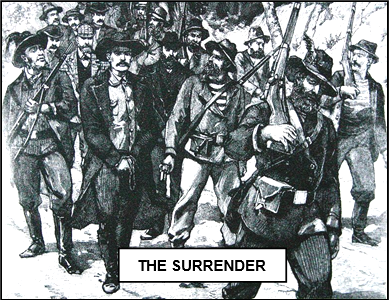

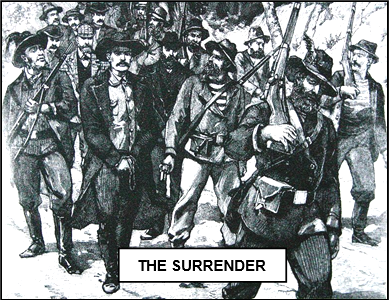

Surrender:

published in the French newspaper Le Petit

Parisien (1876-1944) in 1896, artist unknown. Wilhelm

II: detail, by the English portrait painter Arthur

Stockdale Cope (1857-1940), 1895 – Royal Collection, UK. Kruger: 1879, photographer unknown. Jameson:

by the Irish studio photographer George Charles Beresford (1864-1938),

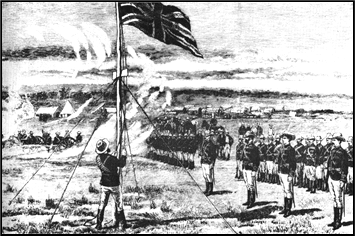

1913 – National Portrait Gallery, London. Mashonaland: date and artist unknown, contained in The

British South African Colonial Historical Catalogue and Souvenir of Rhodesia,

Empire Exhibition, Johannesburg, 1936-1937. Shangani

Patrol: by the Scottish painter Allan Stewart

(1865-1951), 1896, contained in South

Africa and the Transvaal War by Louis Creswicke,

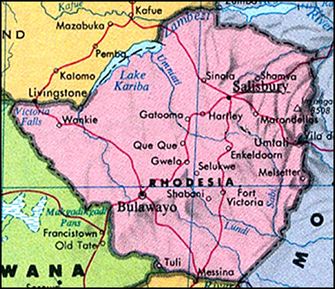

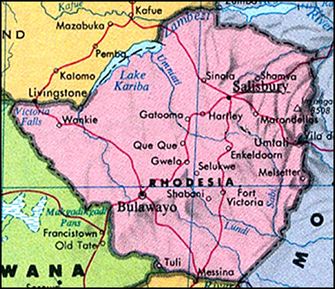

published 1900 – The Project Gutenberg. Map

(Rhodesia): from www.rhodesiandays.com. Raid:

date and artist unknown. Grave: by

photographer Geoff Cooke.

xxxxxAs we have seen, by the First Anglo-Boer War,

ending in 1881,

the Boer state of Transvaal regained its independence, lost in

1877. From the British point of view it was an humiliating defeat,

both from the political and military point of view. The liberal

government, led by prime minister William Gladstone, - a man

opposed to colonialism - was prepared to let matters rest,

but for many in high places and in the public at large, it was a

defeat that needed to be avenged.

xxxxxAs we have seen, by the First Anglo-Boer War,

ending in 1881,

the Boer state of Transvaal regained its independence, lost in

1877. From the British point of view it was an humiliating defeat,

both from the political and military point of view. The liberal

government, led by prime minister William Gladstone, - a man

opposed to colonialism - was prepared to let matters rest,

but for many in high places and in the public at large, it was a

defeat that needed to be avenged.

xxxxxThe

opportunity to do so came five years later when large gold

deposits were discovered in the Witwatersrand Basin and other

areas just south of modern-day Johannesburg. This brought a

large influx of fortune seekers into the Transvaal - many

from Britain - and this seriously undermined the stability of

the country. The Boers found themselves outnumbered two to one by

these Uitlanders (foreigners or outsiders) and they feared that

such a situation would provide yet another opportunity for the

British to seize control of the country. They had good cause for

such fears, particularly as London at that time was the capital of

the world’s gold trade, and these new deposits posed a serious

threat to the city’s financial status.

xxxxxTo meet

this crisis the Transvaal government imposed severe restrictions

upon the new comers. For the majority of them, the right to vote

and the right to obtain permanent residency were withheld, and the

income from this new, lucrative industry was heavily taxed. But

this policy only served to make matters worse. The new-comers

strongly objected to such treatment and opposition mounted. In the

gold-rush town of Johannesburg - where the Uitlanders

were in large numbers - there was open talk of insurrection,

and a plan was drawn up to seize the armoury at Pretoria. As we

have seen, for Cecil Rhodes, then governor of the Cape Colony,

this was an opportunity not to be missed. In mid-1895 he

conceived of a small private army, recruited by the British South

African Company, which, by marching on Johannesburg when the

rising took place - ostensibly to “restore order” -

would spark off a general uprising and bring about the overthrow

of the Transvaal government. That country and the Orange Free

State could then be formed into a federation under British

control, and his De Beers Mining Corporation would be free to take

over the gold mining industry based in Johannesburg.

xxxxxFor this

purpose an armed column, made up of some 600 men and reinforced by

a number of machine guns and some light artillery pieces, was

assembled in Rhodesia, the British colony to the north. Placed

under the command of Leander Starr Jameson, Cecil Rhodes’ right-hand

man, it was stationed at Pitsani on the Transvaal border, ready to

move once news of an uprising in Johannesburg had been received.

But Jameson waited in vain. A dispute had broken out between the

foreign workers in Johannesburg as to what form of administration

would replace the Boer government once it had been overthrown.

Eventually Jameson, growing impatient , decided to go ahead with

the proposed invasion,  believing

that he could spearhead the insurrection on arriving at

Johannesburg. He sent a telegraph message to Rhodes telling him of

his intention and, receiving no immediate reply, cut the telegraph

lines on the morning of the 29th December 1895

and led his small army

into the Transvaal.

believing

that he could spearhead the insurrection on arriving at

Johannesburg. He sent a telegraph message to Rhodes telling him of

his intention and, receiving no immediate reply, cut the telegraph

lines on the morning of the 29th December 1895

and led his small army

into the Transvaal.

xxxThe

“Jameson Raid”, as it came to be called, was a complete failure. He

hoped to be in Johannesburg within three days, before the Boers had

had time to mobilise, but he failed to cut the telegraph line to

Pretoria, and, as a result, the Boers were able to keep track of the

invasion force from the moment it crossed the border. On the 1st

January 1896 Jameson found the road

blocked at Kurgersdopr and, following a brief skirmish, was forced

to make a diversion. Thexnext day he came

face to face with a large Boer force, equipped with artillery, at Doornkop, a ridge some 20 miles west of

Johannesburg. There was no possibility of success. After some hours

of resistance, he was forced to surrender and taken prisoner (illustrated).

xxxxxJameson was

imprisoned in Pretoria, and then returned to London for his trial.

At the end of February 1896 he was found guilty of leading the

raid and sentenced to 15 months in prison, but he was released in

December on health grounds. By way of compensation the Transvaal

government was paid a sum close to £1 million by the British South

Africa Company. Cecil Rhodes, the man who had planned the raid,

was forced to resign as prime minister of the Cape Colony and that

brought an end to his political career. The part played in the

affair by the British colonial secretary Joseph Chamberlain was

also questioned. He had known of the plan, but at his trial

Jameson did not implicate him, and he was subsequently cleared of

any wrong-doing by an investigation conducted by a select

committee of the House of Commons. In the Transvaal the leading

members of the Reform Committee, which had been scheming on behalf

of the Uitlander population, - including Colonel Frank Rhodes

(brother of Cecil Rhodes) - were charged and found guilty of

high treason for collaborating with Jameson. They were sentenced

to death in April, but released two months later on the payment of

heavy fines.

xxxxxIn Britain,

the outcome of the raid created a great deal of anti-Boer

feeling, and lit the fuse for the Second Anglo-Boer War.

Indeed, for many it was seen as a just cause for war. Jameson was

regarded as a hero, a brave upholder of the British Empire and the

rights of the individual. And there was, too, a great deal of

animosity towards Germany. After the surrender of Jameson’s

raiding party, the German Kaiser, Wilhelm II (illustrated), had sent a

message to Paul Kruger, the Transvaal prime minister, (the famous

“Kruger telegram”) congratulating him upon his victory. There was

talk of Germany providing the Boers with arms, and of the need for

Britain to reassert its authority before it was too late. Indeed,

the failure of the raid only served to highlight the fact that the

plight of the Uitlanders remained and had to be addressed.

xxxxxAs we shall

see, after some unproductive negotiations, in September 1899 the

British government - clearly determined to regain control

over what was now a profitable area - delivered an ultimatum

to Paul Kruger (illustrated) demanding the immediate enfranchisement of all white

Uitlanders. There was no possibility of compliance, and the Second

Anglo-Boer War broke out in October 1899. It was to prove a long and bloody conflict, and one

which was to have important consequences for the future of South

Africa and the British Empire.

xxxxxIncidentally, British anger and fears concerning the “Kruger

Telegram” were well founded. As we shall see, following the

Jameson Raid, the Transvaal bought a great deal of military

equipment from Germany, and this served them well during the

Second Anglo-Boer War. And the Kaiser’s interest in south-east

Africa (Germany already had colonies in the west, south-west

and east of the continent) was followed in 1897 by the first of

Germany’s Naval Bills, clearly designed - as the War Office

saw it - to challenge Britain’s supremacy at sea. In a matter

of a few years, German ambition to play a part on the world stage

was to lead to British reconciliation with France and Russia, the

formation of two armed camps on the continent (The Triple Entente

and the Central Powers) and, eventually, the First World War of

1914 to 1918. ……

xxxxx…… The Jameson Raid had an indirect effect upon the

affairs of the neighbouring state of Rhodesia, the two territories

of Matabeleland and Mashonaland which were combined and named

after Cecil Rhodes in 1895. The withdrawal of the white police

force from this state to take part in the raid encouraged the

natives to take up arms against the British South Africa Company

and, as we shall see, this led to The Second Matabele War of 1896.

Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc

Including:

Leander Starr Jameson

xxxxxThe Scotsman

Leander Starr Jameson

(1853-1917) went to school in London and trained as a surgeon

at University College Hospital. He gained a reputation for his

work as a doctor, but, because of ill-health, in 1878 he went

out to Cape Colony in South Africa to benefit from a warmer

climate. There he struck up a close friendship with the diamond

magnate and politician Cecil Rhodes, and numbered among his

patients the statesman Paul Kruger and Lobengula, the King of the

Matabele. In order to assist Rhodes in his colonial ambitions and

his search for gold, in 1888 he persuaded Lobengula to grant

Rhodes mining rights in Mashonaland, a territory north of the

River Limpopo. In 1890, anxious like Rhodes to consolidate British

rule throughout South Africa, he abandoned his medical practice

and led a pioneer column to open the way to Mashonaland and claim

this area for the British South Africa Company. This alarmed

Lobengula. He invaded Mashonaland to prove his authority over the

region and, as we have seen, this caused the First Matabele War of

1893. Jameson

directed the campaign and the British force, small but well armed,

won the conflict. Matabeleland was then annexed for the British

crown. Jameson was now seen as a colonial statesmen of stature,

but then came the Jameson Raid of 1896, a foolhardy attempt, as we have seen, to invade the

Transvaal and trigger off a national uprising against the Boer

government. Its failure landed him in prison, but after his

release he returned to South African politics. He served as prime

minister for the Cape Colony from 1904 to 1908, assisted in the

formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, and was then a

member of the Unionist Party for two years. Before returning home

he was created a baronet. Despite the debacle of the Jameson Raid,

he remained highly regarded for his patriotism, the quality of his

leadership, and his work in consolidating Britain’s hold over the

greater part of South Africa.

xxxxxLeander Starr Jameson (1853-1917)

was a doctor by profession (known to his close friends as “Doctor

Jim”), but later in life he became a colonial administrator and

statesmen in South Africa. He was born in Edinburgh, where his

father, Robert William Jameson - known for his reformist

ideas - was editor of the Wigtownshire Free Press. During his

early years the family moved to London, living in Chelsea and then

Kensington. He attended Godolphin School in Hammersmith, and then

trained as a surgeon at University College Hospital. After

qualifying he gained a reputation for his medical skill and his

lectures on anatomy, but he fell ill from over working and

eventually decided to settle in South Africa, where he hoped the

warmer climate would assist in his recovery.

xxxxxLeander Starr Jameson (1853-1917)

was a doctor by profession (known to his close friends as “Doctor

Jim”), but later in life he became a colonial administrator and

statesmen in South Africa. He was born in Edinburgh, where his

father, Robert William Jameson - known for his reformist

ideas - was editor of the Wigtownshire Free Press. During his

early years the family moved to London, living in Chelsea and then

Kensington. He attended Godolphin School in Hammersmith, and then

trained as a surgeon at University College Hospital. After

qualifying he gained a reputation for his medical skill and his

lectures on anatomy, but he fell ill from over working and

eventually decided to settle in South Africa, where he hoped the

warmer climate would assist in his recovery.

xxxxxHe set up a

practice at Kimberley in 1878, and it was not long before he came

to know the leading political figures in the Cape Colony. He

numbered among his patients Paul Kruger, the South African statesman, and the Matabale chief Lobengula

- who honoured him with the title

of InDuna, meaning Advisor - and

he struck up a close friendship with the politician and diamond

magnate Cecil Rhodes. It was in order to assist Rhodes in his

colonial and business ambitions that he persuaded Lobengula to

grant what came to be known as the Rudd Concession (Rudd being one

of Rhodes’ agents) in 1888. This simply allowed the British to

carry out mining operations on the land situated between the

Limpopo and Zambia Rivers. In return Rhodes provided the Matabele

chief with a monthly payment, a large number of rifles, and a

steamboat on the Zambesi.

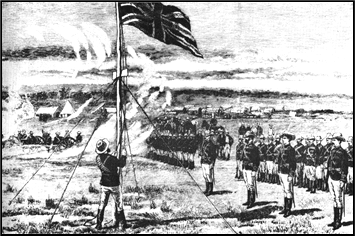

xxxxxIt was on the strength of this agreement -

reached in large measure by the good offices of Jameson -

that in 1889 Rhodes founded the British South Africa Company. The

following year, Rhodes having become prime minister of the Cape

Colony, Jameson decided to abandon his medical practice and

support Rhodes in his colonial ambitions. Like Rhodes, he was

anxious to consolidate British hold over the whole of South Africa

before others - be it the Germans, Portuguese or Boers -

seized valuable territory. He therefore agreed to take command of

a pioneer column made up of 180 volunteers and 200 armed police,

charged with the task of clearing a way through Matabeleland and

taking control of Mashonaland, an area thought to be rich in gold

deposits. Beginning in the July, the expedition made good progress

despite the difficult terrain through which it had to force a way

over a distance of some 425 miles. It entered Mashonaland, setting

up forts en route, and in September, having established Fort

Salisbury, raised the union jack (illustrated) and claimed the territory for the British crown -

in the guise of the British South Africa Company. In 1891 Jameson

was appointed administrator of Mashonaland, the traditional home of

the Shona people.

xxxxxIt was on the strength of this agreement -

reached in large measure by the good offices of Jameson -

that in 1889 Rhodes founded the British South Africa Company. The

following year, Rhodes having become prime minister of the Cape

Colony, Jameson decided to abandon his medical practice and

support Rhodes in his colonial ambitions. Like Rhodes, he was

anxious to consolidate British hold over the whole of South Africa

before others - be it the Germans, Portuguese or Boers -

seized valuable territory. He therefore agreed to take command of

a pioneer column made up of 180 volunteers and 200 armed police,

charged with the task of clearing a way through Matabeleland and

taking control of Mashonaland, an area thought to be rich in gold

deposits. Beginning in the July, the expedition made good progress

despite the difficult terrain through which it had to force a way

over a distance of some 425 miles. It entered Mashonaland, setting

up forts en route, and in September, having established Fort

Salisbury, raised the union jack (illustrated) and claimed the territory for the British crown -

in the guise of the British South Africa Company. In 1891 Jameson

was appointed administrator of Mashonaland, the traditional home of

the Shona people.

xxxxxBut the

activities of the Company, whilst in accordance with its charter -

granted by the British government - went far beyond the Rudd

Concession of 1888, and this alarmed Lobengula. In order to assert

his authority over Mashonaland - a tributary state - in

July 1893 he mounted an invasion of the territory to bring to heel

a dissident chief in the area of Victoria. This gave Jameson the

opportunity he was looking for to extend British control even

further. On the grounds that to take no action would undermine his

authority with the Mashona and he would lose their loyalty, he

ordered Lobengula to withdraw his troops and, when he refused to

do so, sought support for action from Rhodes and the home

government. Having received approval, he prepared an army to

invade Matebeleland.

xxxxxAs we have

seen, the First Matabele War of 1893, in which Jameson assumed

direction of the campaign, gave the British total control over Matabeleland. The forces

of the British South Africa Company, though heavily outnumbered,

had a decisive advantage in firepower. Victory in the battles of

the Bembesi and Singuesi Rivers, achieved by the effectiveness of

the Maxim machine gun and the rapid-firing rifle, convinced

Lobengula that further resistance was futile. He fled with his

army into the bush after burning Bulawayo, his capital, to the

ground. Jameson, in order to bring the conflict to a speedy end,

ordered a march on Bulawayo and then, having learnt of the

whereabouts of Lobengula, sent out a column to capture the king.

This resulted in the loss of the Shangani Patrol in the December,

- when an advance guard of some 30 men was surrounded and

slaughtered (illustrated) - but in January 1894 Lobengula died, and the

Matabele (Ndebele) laid down their arms.

xxxxxFollowing the death of

Lobengula, Jameson was appointed the first administrator of

Matabeleland and, on returning to Britain at the end of the year,

along with Rhodes, was feted as a hero. On his return to South

Africa in the spring of 1895, the two territories of Matabeleland

and Mashonaland were officially named Rhodesia in honour of the

architect of British imperialism.

xxxxxFollowing the death of

Lobengula, Jameson was appointed the first administrator of

Matabeleland and, on returning to Britain at the end of the year,

along with Rhodes, was feted as a hero. On his return to South

Africa in the spring of 1895, the two territories of Matabeleland

and Mashonaland were officially named Rhodesia in honour of the

architect of British imperialism.

xxxxxBut

Jameson’s reputation as a colonial diplomat, though not

irreparably damaged, received a severe blow, as we have seen, with

the infamous Jameson Raid, defeated in 1896. It was originally intended to be made in support of

a revolt among the discontented Uitlanders of Johannesburg -

those foreigners (or outsiders) who had flooded into the Transvaal

in search of gold - and thereby trigger off a general

uprising against the Boer government. But despite the fact that no revolt took place in the city, Jameson nonetheless

launched the invasion in December 1895. It was, as it proved to

be, a foolhardy miscalculation on his part. The armed column, made

up of some 600 men and supported with only a small amount of light

artillery, was harassed from the time it crossed the border, and

forced to accept a humiliating defeat at Doornkop five days later

on the 2nd January 1896. Jameson was

captured, sent to England for trial, and sentenced to fifteen

months imprisonment, though he was released earlier due to ill-health.

that no revolt took place in the city, Jameson nonetheless

launched the invasion in December 1895. It was, as it proved to

be, a foolhardy miscalculation on his part. The armed column, made

up of some 600 men and supported with only a small amount of light

artillery, was harassed from the time it crossed the border, and

forced to accept a humiliating defeat at Doornkop five days later

on the 2nd January 1896. Jameson was

captured, sent to England for trial, and sentenced to fifteen

months imprisonment, though he was released earlier due to ill-health.

xxxxxThis

debacle resulted in deep embarrassment for the British government,

particularly as it was alleged that the Colonial Secretary had

known and approved of the raid, and it also soured relations with

Germany following the famous “Kruger telegram”, but nonetheless

the conduct of Jameson during his trial won him a great deal of

support. He stoically accepted blame for the raid, implicated no

others, and won approval for what the public saw as his commitment

- be it over zealous - to the well being of the

Uitlanders (many of them British) who were denied their basic

rights by the Transvaal government. Indeed, as we shall see, it

was the continued plight of the Uitlanders which was to bring

about The Second Anglo-Boer War of 1899.

xxxxxJameson took no part in this second conflict with the

Boers, but on his return to South Africa he became leader of the

Progressive Party in Cape Colony in 1903 and, following the

party’s success at the polls, served as prime minister from 1904

to 1908. After the founding of the Union of South Africa (The

Cape, Natal, Transvaal and Orange Free State) in which he played a

part, he was a member of the Unionist Party from 1910 to 1912, and

before returning home was created a baronet. He died in London in

November 1917 and was buried in a vault at Kensal Green cemetery,

but after the end of the First World War his body was taken to

South Africa and buried at Malindidzimu Hill (World’s View) in

Matabo National Park, some 25 miles south of Bulawayo, alongside

the grave of his close friend Cecil Rhodes. This granite hill was

designated by Rhodes as a resting place for those who had served

Great Britain well in Africa.

xxxxxJameson took no part in this second conflict with the

Boers, but on his return to South Africa he became leader of the

Progressive Party in Cape Colony in 1903 and, following the

party’s success at the polls, served as prime minister from 1904

to 1908. After the founding of the Union of South Africa (The

Cape, Natal, Transvaal and Orange Free State) in which he played a

part, he was a member of the Unionist Party from 1910 to 1912, and

before returning home was created a baronet. He died in London in

November 1917 and was buried in a vault at Kensal Green cemetery,

but after the end of the First World War his body was taken to

South Africa and buried at Malindidzimu Hill (World’s View) in

Matabo National Park, some 25 miles south of Bulawayo, alongside

the grave of his close friend Cecil Rhodes. This granite hill was

designated by Rhodes as a resting place for those who had served

Great Britain well in Africa.

xxxxxIncidentally, the British

writer and poet Rudyard Kipling, himself a fervent patriot and

imperialist, was a great admirer of Jameson and got to know him on

his visits to South Africa. He applauded his personal qualities,

such as his courage, dignity, and stoicism, and let it be known

that his famous poem If “was drawn

from Jameson’s character”. The line: If you can

keep your head when all about you are losing theirs and blaming

it on you, aptly sums up the way Jameson handled the

furore which followed the Jameson Raid, a disaster of his own

making. ……

xxxxxIncidentally, the British

writer and poet Rudyard Kipling, himself a fervent patriot and

imperialist, was a great admirer of Jameson and got to know him on

his visits to South Africa. He applauded his personal qualities,

such as his courage, dignity, and stoicism, and let it be known

that his famous poem If “was drawn

from Jameson’s character”. The line: If you can

keep your head when all about you are losing theirs and blaming

it on you, aptly sums up the way Jameson handled the

furore which followed the Jameson Raid, a disaster of his own

making. ……

xxxxx…… According to some accounts, after the Jameson Raid

it was the wealthy diamond trader Barney Barnato who negotiated

with his friend Paul Kruger, the Boer president, and managed to

get all his pals released from prison and sent to England for

their trial. ……

xxxxx…… Jameson’s unusual first names came about from an

incident which occurred on the morning of his birth. His father

was walking along a stretch of canal or river on the day his

twelfth child was due to be born when he slipped and fell into the

water. A passer-by, an American traveller named Leander

Starr, fished him out and, to show his gratitude, his father named

his new son after him!

xxxxxAs we have seen, by the First Anglo-

xxxxxAs we have seen, by the First Anglo- believing

that he could spearhead the insurrection on arriving at

Johannesburg. He sent a telegraph message to Rhodes telling him of

his intention and, receiving no immediate reply, cut the telegraph

lines on the morning of the 29th December 1895

and led his small army

into the Transvaal.

believing

that he could spearhead the insurrection on arriving at

Johannesburg. He sent a telegraph message to Rhodes telling him of

his intention and, receiving no immediate reply, cut the telegraph

lines on the morning of the 29th December 1895

and led his small army

into the Transvaal.

xxxxxLeander Starr Jameson (1853-

xxxxxLeander Starr Jameson (1853- xxxxxIt was on the strength of this agreement -

xxxxxIt was on the strength of this agreement -

xxxxxFollowing the death of

Lobengula, Jameson was appointed the first administrator of

Matabeleland and, on returning to Britain at the end of the year,

along with Rhodes, was feted as a hero. On his return to South

Africa in the spring of 1895, the two territories of Matabeleland

and Mashonaland were officially named Rhodesia in honour of the

architect of British imperialism.

xxxxxFollowing the death of

Lobengula, Jameson was appointed the first administrator of

Matabeleland and, on returning to Britain at the end of the year,

along with Rhodes, was feted as a hero. On his return to South

Africa in the spring of 1895, the two territories of Matabeleland

and Mashonaland were officially named Rhodesia in honour of the

architect of British imperialism.  that no revolt took place in the city, Jameson nonetheless

launched the invasion in December 1895. It was, as it proved to

be, a foolhardy miscalculation on his part. The armed column, made

up of some 600 men and supported with only a small amount of light

artillery, was harassed from the time it crossed the border, and

forced to accept a humiliating defeat at Doornkop five days later

on the 2nd January 1896. Jameson was

captured, sent to England for trial, and sentenced to fifteen

months imprisonment, though he was released earlier due to ill-

that no revolt took place in the city, Jameson nonetheless

launched the invasion in December 1895. It was, as it proved to

be, a foolhardy miscalculation on his part. The armed column, made

up of some 600 men and supported with only a small amount of light

artillery, was harassed from the time it crossed the border, and

forced to accept a humiliating defeat at Doornkop five days later

on the 2nd January 1896. Jameson was

captured, sent to England for trial, and sentenced to fifteen

months imprisonment, though he was released earlier due to ill- xxxxxJameson took no part in this second conflict with the

Boers, but on his return to South Africa he became leader of the

Progressive Party in Cape Colony in 1903 and, following the

party’s success at the polls, served as prime minister from 1904

to 1908. After the founding of the Union of South Africa (The

Cape, Natal, Transvaal and Orange Free State) in which he played a

part, he was a member of the Unionist Party from 1910 to 1912, and

before returning home was created a baronet. He died in London in

November 1917 and was buried in a vault at Kensal Green cemetery,

but after the end of the First World War his body was taken to

South Africa and buried at Malindidzimu Hill (World’s View) in

Matabo National Park, some 25 miles south of Bulawayo, alongside

the grave of his close friend Cecil Rhodes. This granite hill was

designated by Rhodes as a resting place for those who had served

Great Britain well in Africa.

xxxxxJameson took no part in this second conflict with the

Boers, but on his return to South Africa he became leader of the

Progressive Party in Cape Colony in 1903 and, following the

party’s success at the polls, served as prime minister from 1904

to 1908. After the founding of the Union of South Africa (The

Cape, Natal, Transvaal and Orange Free State) in which he played a

part, he was a member of the Unionist Party from 1910 to 1912, and

before returning home was created a baronet. He died in London in

November 1917 and was buried in a vault at Kensal Green cemetery,

but after the end of the First World War his body was taken to

South Africa and buried at Malindidzimu Hill (World’s View) in

Matabo National Park, some 25 miles south of Bulawayo, alongside

the grave of his close friend Cecil Rhodes. This granite hill was

designated by Rhodes as a resting place for those who had served

Great Britain well in Africa. xxxxxIncidentally, the British

writer and poet Rudyard Kipling, himself a fervent patriot and

imperialist, was a great admirer of Jameson and got to know him on

his visits to South Africa. He applauded his personal qualities,

such as his courage, dignity, and stoicism, and let it be known

that his famous poem If “was drawn

from Jameson’s character”. The line: If you can

keep your head when all about you are losing theirs and blaming

it on you, aptly sums up the way Jameson handled the

furore which followed the Jameson Raid, a disaster of his own

making. ……

xxxxxIncidentally, the British

writer and poet Rudyard Kipling, himself a fervent patriot and

imperialist, was a great admirer of Jameson and got to know him on

his visits to South Africa. He applauded his personal qualities,

such as his courage, dignity, and stoicism, and let it be known

that his famous poem If “was drawn

from Jameson’s character”. The line: If you can

keep your head when all about you are losing theirs and blaming

it on you, aptly sums up the way Jameson handled the

furore which followed the Jameson Raid, a disaster of his own

making. ……