xxxxxAs we have seen, the death of Ferdinand VII of Spain in 1833 (W4), and the accession of his daughter Isabella II, brought about the First Carlist War, led by the pretender to the throne Don Carlos, Ferdinand’s brother. He failed to depose his niece after seven years of fighting, and the Second Carlist War of 1846 to 1849 also proved unsuccessful. However, following the collapse of Isabella’s disastrous reign in 1868 and her escape to France, the army took control of the country. A constitutional monarch was eventually enthroned (Amadeus, Duke of Aosta), but, faced with growing unrest and the Cuban Revolt, he abdicated in 1873. A republican government was then formed, and in the ensuing chaos Don Carlos, the grandson of Don Carlos, Ferdinand’s brother, led his forces in the Third Carlist War (1872-

QUEEN ISABELLA II OF SPAIN IS FORCED

TO ABDICATE 1868 (Vb)

Acknowledgements

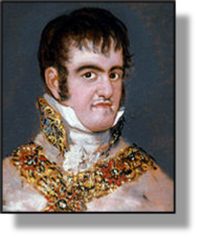

Ferdinand VII: detail, by the Spanish painter Francisco de Goya (1746-

xxxxxFollowing the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Ferdinand VII (illustrated) returned as king of Spain in 1814. He agreed to accept the democratic form of government which had been established two years earlier, but once in power he turned back the political clock and reintroduced a reactionary regime, ruthlessly suppressing any move towards democratic reform. For a short while a revolution in 1820 did manage to restore parliamentary government, but then the French, acting through the Holy Alliance, sent a large army into Spain and put Ferdinand firmly back on his throne.

xxxxxFollowing the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Ferdinand VII (illustrated) returned as king of Spain in 1814. He agreed to accept the democratic form of government which had been established two years earlier, but once in power he turned back the political clock and reintroduced a reactionary regime, ruthlessly suppressing any move towards democratic reform. For a short while a revolution in 1820 did manage to restore parliamentary government, but then the French, acting through the Holy Alliance, sent a large army into Spain and put Ferdinand firmly back on his throne.

xxxxxAs we have seen, with his death in 1833 (W4) troubles broke out again. By prior agreement of the Cortes (the Spanish parliament), he was succeeded by his daughter Isabella, then only three years old, but his brother Don Carlos, claiming to be the rightful heir to the throne, began the First Carlist War. An arch reactionary, like his brother, he gained support from the mountain provinces of the north -

xxxxxAnother Carlist attempt to seize the throne took place in the mid 1840s - instability and civil unrest. She presided over no less than sixty changes of government as part of the continuing struggle between the supporters of absolute monarchy, the liberal elements seeking parliamentary reform, and a growing republican movement. She managed to survive a serious threat to her authority in 1866, but was deposed and forced into exile in September 1868

instability and civil unrest. She presided over no less than sixty changes of government as part of the continuing struggle between the supporters of absolute monarchy, the liberal elements seeking parliamentary reform, and a growing republican movement. She managed to survive a serious threat to her authority in 1866, but was deposed and forced into exile in September 1868

xxxxxIn the meantime a great deal was to happen, with monarchy giving way to republic and a rebellion in Cuba threatening to bring Spain to its knees. With the departure of Queen Isabella in 1868, the military, having put down republican risings, were determined to keep control of affairs by giving the country a liberal, constitutional monarchy. They set up a provisional government in which General Serrano was elected Regent, and General Prim was made president of the council, charged with the task of finding a suitable candidate for the Spanish throne. It proved a difficult assignment. A number of foreign princes were approached, but it was not until 1870 that the throne was accepted by Amadeus, Duke of Aosta, a son of King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy. He was duly elected, but Prim, his staunch supporter, was assassinated in December 1870, just before he arrived in Spain, and his short reign was beset with difficulties. As a foreigner he was not popular, the republicans strongly opposed his “appointment”, and an insurrection in Cuba was proving a serious drain on men and money. Furthermore, the Carlists, led by Don Carlos, Duke of Madrid (1848-

xxxxxIn the political confusion that followed the radical members in the Cortes took the opportunity to proclaim the first Spanish republic, but it was a government in name only. A weak and disunited Republican Party soon became embroiled with federal extremists, and proved quite incapable of stopping the country’s slide into civil war. It was such a situation that the Carlists had been waiting for. Having gained little support in the elections held in 1872, they decided to put “Carlos VII” on the throne by force of arms. The Third Carlist War was under way.

xxxxxDespite an early setback at the Battle of Oroquieta in Navarre, the Carlists had reached a strength of some 50,000 by February 1873, and during the remainder of the year gained a number of notable victories, such as those at Alpens in Catelonia in July, and Montejurra in Navarre in November. In July the following year they occupied and sacked the town of Cuenca, just 85 miles from Madrid, but they were badly defeated at the Battles of Caspe and Gandesa, and in May they were forced to lift their four-

xxxxxDespite an early setback at the Battle of Oroquieta in Navarre, the Carlists had reached a strength of some 50,000 by February 1873, and during the remainder of the year gained a number of notable victories, such as those at Alpens in Catelonia in July, and Montejurra in Navarre in November. In July the following year they occupied and sacked the town of Cuenca, just 85 miles from Madrid, but they were badly defeated at the Battles of Caspe and Gandesa, and in May they were forced to lift their four-

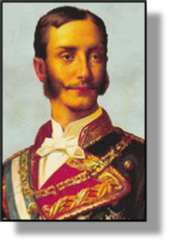

xxxxxThe failure of the third and final Carlist War was not totally surprising. The leadership of Don Carlos (illustrated) had lacked urgency, and in general his forces had not been able to match the skill and equipment of the government troops, especially in siege warfare. And particularly crucial was the fact that Catalonia and the Basque states of the north (illustrated) -

xxxxxThe failure of the third and final Carlist War was not totally surprising. The leadership of Don Carlos (illustrated) had lacked urgency, and in general his forces had not been able to match the skill and equipment of the government troops, especially in siege warfare. And particularly crucial was the fact that Catalonia and the Basque states of the north (illustrated) -

xxxxxFollowing the defeat of the Carlists and the crushing of the Cuban rebellion in 1878, the reign of Alfonso XII brought a much welcomed period of peace and stability. Furthermore the country’s economy received a temporary boost from an increased demand for iron ore, wine and wool. However, the peace settlement of El Zanjon which ended the Cuban insurrection of 1878 did not hold. Another large scale revolt broke out in 1895, and this time the United States intervened. As we shall see, this led to the Spanish-

xxxxxIncidentally, during the reign of Queen Isabella II the so-

xxxxx…… And a much more serious result arising out of the troubles in Spain occurred in 1869 when General Prim, looking for a constitutional monarchy, attempted to persuade Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern-

xxxxx…… General Prim later remarked that looking for a democratic monarch in Europe was like “trying to find an atheist in heaven”.

Including:

The Third Carlist War

and The Cuban Revolt

Vb-

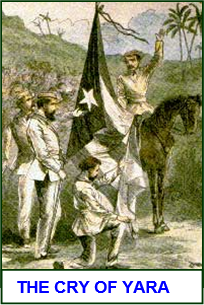

xxxxxThe overthrow of Isabella II in 1868 and the political ferment that followed in its wake led directly to the Cuban Revolt, the so called Ten Years’ War. Cubans seized the opportunity to declare independence and launch a guerrilla war against the government forces, numbering some 100,000 by 1870. The rebels fought well but by 1878 their casualties had risen to 200,000. With no sign of intervention by the United States, they decided to sue for peace. By the Treaty of El Zanjon in February 1878 they were promised political reforms and the abolition of slavery. However, when some of these promises were not kept, they rebelled again in 1885. As we shall see, this led to the Spanish-

xxxxxAndxthe unrest at home led directly to the Cuban Revolt, the so-

xxxxxAndxthe unrest at home led directly to the Cuban Revolt, the so-

xxxxxAlthough the conflict was limited almost entirely to the eastern side of the island and, for the most part, took the form of guerrilla warfare, it was nonetheless a savage encounter and became more so  as the fighting progressed. As such, it placed great demands upon the Spanish government, both in men and money. By 1870 there were no less than 100,000 government troops stationed on the island. In their hit-

as the fighting progressed. As such, it placed great demands upon the Spanish government, both in men and money. By 1870 there were no less than 100,000 government troops stationed on the island. In their hit-

xxxxxThexTreaty of El Zanjon, signed in February 1878, did promise various political reforms and the abolition of slavery, but when some of these promises were not kept, a further rebellion broke out in 1895. As we shall see, U.S. support for the Cuban revolutionaries was to lead to the Spanish-

xxxxxIncidentally, one of the prominent leaders in Cuba’s struggle for independence was Antonio Maceo (1845-

xxxxx…… The 10th October, the date of the declaration of independence (the ”Cry of Yara”), is marked by a national holiday in Cuba. ……

xxxxx…… The Spanish forces, unaccustomed to the island’s climate, lost more men from yellow fever than from the fighting.