xxxxxIt was the year after the Fenian Uprising of 1867 (Vb) that the British Liberal prime minister William Gladstone set himself the task of pacifying Ireland. For the next twenty years, however, the island was torn apart by the so-called Land War, a violent period of civil unrest. Gladstone was obliged to introduce “coercion laws” - which included imprisonment without trial - in an attempt to put an end to the constant conflict between the English landlords and their impoverished tenant farmers. At the same time, however, he introduced two Land Acts in the early 1880s to try to solve the agrarian problem. These met with some success, but in May 1882, as we have seen, the Phoenix Park Murders, the stabbing to death of two senior Irish ministers as a reprisal against the coercion laws, shocked Victorian society. Gladstone gradually came to the view that some form of home rule for Ireland was necessary to bring an end to the problems. In this he was supported by the Irish politician Charles Stewart Parnell, the leader of the Irish party at Westminster. In 1885, holding the balance of power, he threw his party behind Gladstone and made possible the introduction of the First Irish Home Rule Bill in April 1886. Largely the work of Gladstone himself, it was strongly opposed by the Conservative opposition and even some members of his own party because it made insufficient provision for the Irish Protestants in the north. The Bill was defeated, and the Second Irish Home Rule Bill, put forward by Gladstone in 1893 after returning to power, was likewise defeated, this time by the House of Lords. A Third Bill, presented in 1912, was passed by the Commons but delayed by the Lords until 1914, and then put on hold by the outbreak of the First World War. By the time this conflict was finished, however, there was no reconciliation between the Catholics and the Protestants, and division was the only answer. In 1921 twenty-six counties were formed into the Irish Free State, and the six Protestant counties in the north remained within the United Kingdom.

THE FIRST AND SECOND IRISH

HOME RULE BILLS 1886 and 1893 (Vc)

Acknowledgements

Irish Home Rule: published in The Illustrated London News, April 1886, artist unknown. Belfast: 1886, artist unknown. Map (Ireland): licensed under Creative Commons – www.wikitree.com/wiki/Categoy:Old_Kingdom_of_

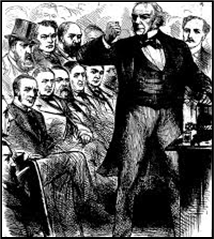

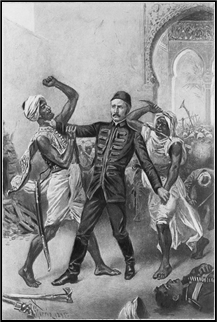

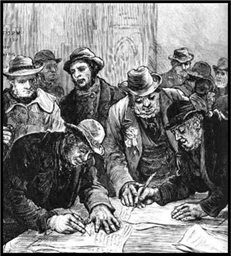

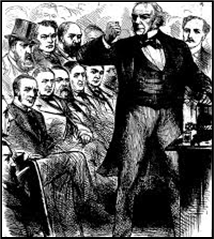

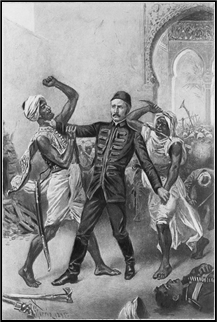

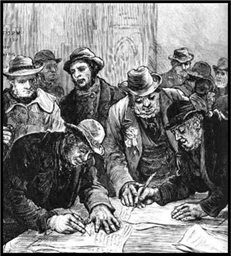

Ireland. Map (Ireland): licensed under Creative Commons – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ei-map.svg. Gladstone: by the London Stereoscopic Company, date unknown. In the Commons: date and artist unknown. Gordon: photomechanic print by the American artist Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (1863-1930), c1895 – Library of Congress, Washington. Voting: published in The Illustrated London News, 1884, artist unknown.

xxxxxIt was the year after the Fenian Uprising of 1867 (Vb) - an attempt to spark off a national rising against British rule - that the British politician William Gladstone, becoming Prime Minister for the first time, publicly declared that his mission was to pacify Ireland. In the political climate of the day, it was an extremely bold pledge to make. From the early 1870s, as we have seen, the island was engulfed in the so-called Land War, a long period of serious social unrest, caused in the main by the plight of the tenant farmer. Plunged into debt by a string of poor harvests and a significant fall in the price of wheat, dairy produce and cattle, the tenant farmers found themselves at the mercy of the English landlord, many of whom did not live on their land. Threatened by eviction they took to attacking the landlord (or his agent), burning his hay, and killing or maiming his livestock. Such was the breakdown in law and order that in 1881 Gladstone was obliged to bring in “coercion” laws whereby troublemakers could be imprisoned without trial on “suspicion” of wrong doing. There followed, by way of reprisal, the Phoenix Park Murders in May 1882 in which two prominent Irish ministers were stabbed to death in Dublin by the “Invincibles”, one of the many secret organisations working for Irish independence at that time.

xxxxxIt was the year after the Fenian Uprising of 1867 (Vb) - an attempt to spark off a national rising against British rule - that the British politician William Gladstone, becoming Prime Minister for the first time, publicly declared that his mission was to pacify Ireland. In the political climate of the day, it was an extremely bold pledge to make. From the early 1870s, as we have seen, the island was engulfed in the so-called Land War, a long period of serious social unrest, caused in the main by the plight of the tenant farmer. Plunged into debt by a string of poor harvests and a significant fall in the price of wheat, dairy produce and cattle, the tenant farmers found themselves at the mercy of the English landlord, many of whom did not live on their land. Threatened by eviction they took to attacking the landlord (or his agent), burning his hay, and killing or maiming his livestock. Such was the breakdown in law and order that in 1881 Gladstone was obliged to bring in “coercion” laws whereby troublemakers could be imprisoned without trial on “suspicion” of wrong doing. There followed, by way of reprisal, the Phoenix Park Murders in May 1882 in which two prominent Irish ministers were stabbed to death in Dublin by the “Invincibles”, one of the many secret organisations working for Irish independence at that time.

xxxxxIt was violence on that scale that convinced Gladstone that a political solution was necessary to bring peace. He had improved the lot of the tenant farmer by two Land Acts (particularly by the second one in August 1881), but such was the bitterness and mistrust within the island that he began to see some form of home rule as the only workable answer. In this he was supported by the Irish politician Charles Stewart Parnell, the president of the Irish National Land League. By his fiery oratory he had, in fact, encouraged tenant farmers to take the law into their own hands, but he strongly opposed extreme acts of violence and, by an agreement reached with Gladstone in April 1882 - the Kilmainham Treaty - he agreed to work for a peaceful solution to the troubles. In the election of November 1885, the Irish parliamentary party at Westminster - which he then led - gained the balance of power between the Conservatives and the Liberals, and this gave him a unique window of opportunity. A minority Conservative government assumed office, but in January 1886 he switched his party’s support to the Liberals. This brought down the Tories, put Gladstone back in power for the third time, and paved the way - so it was hoped - for the establishment of Irish home rule.

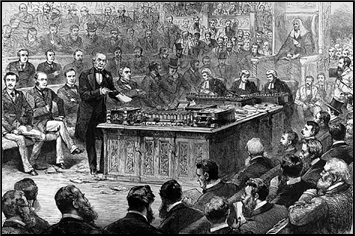

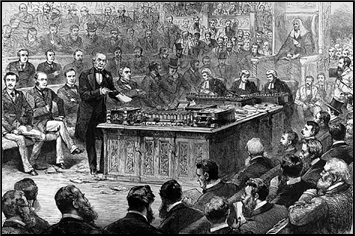

xxxxxThe First Irish Home Rule Bill was introduced in April 1886, and it was very much the work of Gladstone himself. He only had brief discussions with Parnell, and the complete draft was not discussed by cabinet until the last week in March. In broad terms, it proposed the establishment of an Irish legislature in Dublin made up of two orders - the first with 103 peers and landowners, elected for ten years on a restricted franchise, and the second with 204 representatives, elected by the general public. This body would raise its own taxes to meet the cost of administering internal affairs and, in addition, make a contribution to national expenses, such as defence and the running of the Empire. Irish members would not sit in the British Parliament, but foreign policy and external trade would remain a matter for Westminster. A Lord Lieutenant would represent the Queen, and be responsible for appointing ministers and summoning and dissolving the legislature. The Bill provided strong safeguards to prevent any form of religious discrimination, and an additional bill proposed a new land purchasing scheme to solve the vexed problem surrounding the tenant farmer. Gladstone argued passionately that these measures would put an end to Irish obstruction methods in parliament and, given time, bring peace to a troubled land.

xxxxxThe First Irish Home Rule Bill was introduced in April 1886, and it was very much the work of Gladstone himself. He only had brief discussions with Parnell, and the complete draft was not discussed by cabinet until the last week in March. In broad terms, it proposed the establishment of an Irish legislature in Dublin made up of two orders - the first with 103 peers and landowners, elected for ten years on a restricted franchise, and the second with 204 representatives, elected by the general public. This body would raise its own taxes to meet the cost of administering internal affairs and, in addition, make a contribution to national expenses, such as defence and the running of the Empire. Irish members would not sit in the British Parliament, but foreign policy and external trade would remain a matter for Westminster. A Lord Lieutenant would represent the Queen, and be responsible for appointing ministers and summoning and dissolving the legislature. The Bill provided strong safeguards to prevent any form of religious discrimination, and an additional bill proposed a new land purchasing scheme to solve the vexed problem surrounding the tenant farmer. Gladstone argued passionately that these measures would put an end to Irish obstruction methods in parliament and, given time, bring peace to a troubled land.

xxxxxParnell considered that the Bill contained some “great faults and blots”, but, in general, it was warmly welcomed by the Irish Nationalist party and the Irish people. Elsewhere, however, the reception was decidedly frosty. As one would expect, the Tories strongly opposed the bill. They were deeply concerned about the effect it would have on the Protestant Unionists in the north, and exaggerated the possible consequences in order to defeat the bill. ThexConservative Lord Randolph Churchill predicted that “Ulster will fight and Ulster will be right”. And even many who were in favour of Home Rule considered that some of the details were unworkable. How, it was asked, could matters of foreign policy and trade be discussed at Westminster without Irish representation? But the greatest blow against the bill came during its passage, when some ninety Liberals split away and, calling themselves “Liberal Unionists”, formed a political alliance with the Conservatives. Among those who led this revolt was Lord Harrington, the elder brother of Lord Cavendish, one of the two ministers murdered in the Phoenix Park Murders of May 1882. There was fear among these dissident Liberals that home rule would eventually lead to the disintegration of the United Kingdom and, indeed, the Empire itself. On the 8th June the Government was defeated and the bill was thrown out.

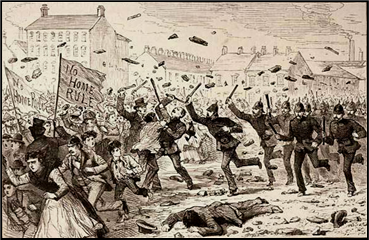

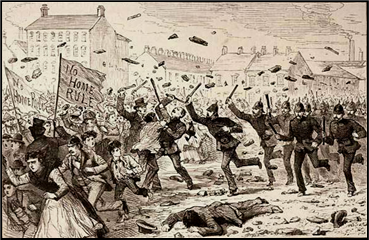

xxxxxIn the general election the following month the Conservatives and the Liberal Unionists gained an overall majority of 118, and this enabled Lord Salisbury (1830-1903) to remain in power until 1892. They were not easy years. The troubles continued unabated. The year 1886 saw some of the worst violence ever seen in Belfast (illustrated), and there were civil disturbances across the land, including an incident in Mitchelstown, County Cork, in which police opened fire on a hostile crowd, killing three people and wounding others. A Crimes Act was introduced in 1887, permitting trial without jury for land related offences, and this put large numbers in prison. Many of the offences were related to the “Plan of Campaign”, a scheme devised by Irish politicians and supported by some Catholic clergy to assist the tenant farmer against extortionate rents. Selected tenants were encouraged to offer what they considered to be a fair rent. If the landlord refused, then the rent would be paid to a committee of trustees and the money would then be used to support tenants who had been evicted.

xxxxxAnd alongside this scheme went “boycotting”, an effective means whereby landlords or their agents were denied any contact with the local community. Many landlords reacted violently against these tactics, evictions increased, and there were killings on both sides.

xxxxxThe year 1892 saw the fall of the Tories and Gladstone’s return to power. He at once set about the drawing up of the Second Irish Home Rule Bill. By that time Parnell was dead, but, as in the previous occasion, the prime minister sought little advice from others. As a result, the draft contained a number of errors - some of them significant - and this hampered and embittered its passage. The new bill contained changes in the format of both levels of the legislature, and, unlike the first attempt, included 80 Irish members in the House of Commons - though their voting was confined to matters affecting Ireland. After long sittings of heated debate the bill was, in fact, passed by the Commons with a narrow margin of 33 votes in September 1893, but it was rejected by the predominantly Conservative House of Lords by 41 votes to 419 later that month. Gladstone resigned from Parliament in 1895 and died three years later, aged 88, his mission unfulfilled.

xxxxxThe year 1892 saw the fall of the Tories and Gladstone’s return to power. He at once set about the drawing up of the Second Irish Home Rule Bill. By that time Parnell was dead, but, as in the previous occasion, the prime minister sought little advice from others. As a result, the draft contained a number of errors - some of them significant - and this hampered and embittered its passage. The new bill contained changes in the format of both levels of the legislature, and, unlike the first attempt, included 80 Irish members in the House of Commons - though their voting was confined to matters affecting Ireland. After long sittings of heated debate the bill was, in fact, passed by the Commons with a narrow margin of 33 votes in September 1893, but it was rejected by the predominantly Conservative House of Lords by 41 votes to 419 later that month. Gladstone resigned from Parliament in 1895 and died three years later, aged 88, his mission unfulfilled.

xxxxxThe first and second Irish Home Rule Bills - debated amid much bitterness - had manifestly served to highlight the deep political division within Ireland itself. Most of the island was Catholic, nationalist and agrarian, but the North East was predominantly Protestant, Unionist and industrialised. Both feared the effects of independence, in part or in full, upon their respective communities. It was not until 1912 that the Liberals introduced the Third Home Rule Bill and by then the lines had been drawn and there was a growing fear of civil war. The Unionists had formed the Ulster Volunteers and the Nationalists had established the Irish Volunteers. Like the second bill, the third was passed by the Commons and rejected by the Lords, but by the Parliamentary Act passed the previous year, the upper chamber could only postpone legislation by two years. When the two years had expired, however, the country was faced with the First World War and, once again, the matter of home rule for Ireland was put on hold.

xxxxxThe four years of war that followed only served to entrench the position of the opposing sides in Ireland. Taking advantage of the government’s preoccupation with war on the continent, the Nationalists launched the Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916. This was quickly crushed and the leading rebels were executed, but by 1918 it was abundantly clear that the demand for an independent Irish republic had replaced any idea of home rule. In the election of that year 73 of the 106 Irish seats were won by members of the Sinn Fein (Ourselves Alone), the Irish Republican Party which had been formed in 1905. These refused to take their seats in Westminster, and set up their own provisional government in Ireland. There followed three years of violent civil disturbance with atrocities on both sides before a partition of Ireland was finally hammered out. In 1921 twenty-six counties were formed into the Irish Free State, and six counties in the north-east - Northern Ireland - remained as part of the United Kingdom.

Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc

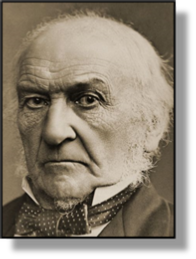

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Liberal politician William Ewart Gladstone (1809-1898) played a major role in Irish politics at the end of the 19th century. Dedicated to finding a peaceful solution to the island’s troubles, he introduced Land Acts to improve the living conditions of the tenant farmer, and his two Home Rule Bills of 1886 and 1893, though unsuccessful, served to point the way to a political solution to the Irish Question. But during sixty years in parliament, many spent as prime minister, Gladstone also played a prominent part in shaping the Liberal Party. In so doing, he introduced a number of important social, monetary and parliamentary reforms, and took a leading role in the Reform Acts of 1867 and 1884. As a man opposed to Imperialism - much in vogue during his years of office - his foreign policy came in for much criticism. Because of the Bulgarian Atrocities, for example, he strongly condemned the Tories’ support of the Turks, and he likewise denounced their policy towards the Afghans, Zulus and Boers in the colonial wars of the late 1870s and early 1880s. But his greatest failure came in 1885. His delay in sending a support column to relieve the siege of Khartoum resulted in the death of General Gordon and his garrison, and this brought widespread condemnation of his foreign policy. His opponents regarded him as pompous and self-righteous, and he was much disliked by Queen Victoria. He failed, in fact, in his two aims, the pacification of Ireland and the abolition of income tax, but he pursued his aims with courage and conviction, and used his skills as an orator in support of good government and peace.

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Liberal politician William Ewart Gladstone (1809-1898) played a prominent role in Irish politics in the closing years of the 19th century. Having publicly declared his aim to “pacify Ireland” in 1868 - at the start of his first term as Prime Minister - he spent the next twenty-five years attempting to accomplish his “mission”. During the Land War he was obliged to take extreme measures to maintain law and order - precipitating the Phoenix Park Murders of May 1882 - but he also produced two Land Acts in the early 1880s, the second of which was particularly successful in easing the friction between the tenant farmer and his landlord. Having come to realise, however, that the troubles could not be fully solved without some form of home rule, his two bills of 1886 and 1893 - though somewhat lacking in the depth required - served notice that only a political settlement could bring a substantial measure of peace. As we have seen, both failed to reach the statute book. The first was defeated by the defection of the Liberal Unionists, and the second was thrown out by a Conservative-dominated House of Lords. He thus died with his mission unaccomplished, but he had brought the issue to the forefront of British politics and gone part of the way to finding a workable solution.

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Liberal politician William Ewart Gladstone (1809-1898) played a prominent role in Irish politics in the closing years of the 19th century. Having publicly declared his aim to “pacify Ireland” in 1868 - at the start of his first term as Prime Minister - he spent the next twenty-five years attempting to accomplish his “mission”. During the Land War he was obliged to take extreme measures to maintain law and order - precipitating the Phoenix Park Murders of May 1882 - but he also produced two Land Acts in the early 1880s, the second of which was particularly successful in easing the friction between the tenant farmer and his landlord. Having come to realise, however, that the troubles could not be fully solved without some form of home rule, his two bills of 1886 and 1893 - though somewhat lacking in the depth required - served notice that only a political settlement could bring a substantial measure of peace. As we have seen, both failed to reach the statute book. The first was defeated by the defection of the Liberal Unionists, and the second was thrown out by a Conservative-dominated House of Lords. He thus died with his mission unaccomplished, but he had brought the issue to the forefront of British politics and gone part of the way to finding a workable solution.

xxxxxBut Gladstone’s attempts at pacifying Ireland was only part of his contribution to British political life. He was Chancellor of the Exchequer on two occasions, 1852 to 1855 and 1859 to 1866, and served as Prime Minister on four occasions, 1868 to 1874, 1880 to 1885, 1886, and 1892 to 1894. During a career spanning over sixty years (1833 to 1894) he made his mark - and quite a number of enemies - both in home and overseas affairs. In his foreign policy in particular he clashed frequently with his Conservative rival and ardent imperialist Benjamin Disraeli, and had the distinction of being rebuked by the Queen herself. Today he is recognised as one of the greatest statesmen of the 19th century.

xxxxxGladstone was born in Liverpool, the son of a wealthy merchant. He was raised as a devout Christian, and religion - with its insistence on moral rectitude - was to play an important part in his political life. After attending Eton, he went up to Oxford and, following a distinguished university career, chose to dedicate his life to politics. He entered Parliament as a Conservative in 1832 and, under Robert Peel, served as president of the Board of Trade and then colonial secretary. Following the collapse of Peel’s government in 1846, he became Chancellor of the Exchequer in Aberdeen’s government until 1859. It was then, having gradually adopted a more progressive policy, that he allied himself with the Liberal Party and continued in the same office under Viscount Palmerston. As an astute parliamentarian, he dominated British politics over much of the next thirty years, ending his career as the “Grand Old Man” of Liberalism.

xxxxxIn home affairs he achieved a number of notable reforms, including competition for entry to the civil service, the introduction of state-supported elementary education, and voting by secret ballot. And in addition to a series of tax reforms and a monetary policy which aimed at the eventual abolition of income tax (though he never achieved it!), his contribution to the Reform Acts of 1867 and 1884 made him a champion of the lower classes - “the people’s William”. In foreign affairs, however, his policy, based on moral but not always practical grounds, attracted much criticism. He was no imperialist and regarded any form of aggressive foreign policy as an outburst of “that dreadful military spirit”.

xxxxxIn home affairs he achieved a number of notable reforms, including competition for entry to the civil service, the introduction of state-supported elementary education, and voting by secret ballot. And in addition to a series of tax reforms and a monetary policy which aimed at the eventual abolition of income tax (though he never achieved it!), his contribution to the Reform Acts of 1867 and 1884 made him a champion of the lower classes - “the people’s William”. In foreign affairs, however, his policy, based on moral but not always practical grounds, attracted much criticism. He was no imperialist and regarded any form of aggressive foreign policy as an outburst of “that dreadful military spirit”.

xxxxxAs early as 1839 he made himself unpopular by arguing that the First Opium War was totally unjust, and during the Russian-Turkish War of 1877 (Vb) he launched a bitter attack upon the government of his Conservative rival Benjamin Disraeli. Appalled by the atrocities committed by the Turks against Christians (the Bulgarian Atrocities), he roundly denounced the pro-Turkish policy of the Tories, though, for its time, it was a credible policy deliberately aimed at curbing Russian influence in the Balkans and, from thence, the eastern Mediterranean. This stance was opposed not only by the opposition, but by elements within his own party, the public in general, and the Queen in particular.

xxxxxThen in 1880 he alarmed the foreign office and the military by withdrawing British garrisons from Kabul and Kandahar, two strongholds designed to strengthen Afghanistan against Russian designs upon British India. The following year saw the outbreak of the First Anglo-Boer War and the humiliating defeat of the British at the Battle of Majuba Hill. In Britain there was a public demand for revenge, but Gladstone, opposed to colonial adventures, favoured a settlement, and by the Convention of Pretoria in April 1881 the Transvaal regained its independence.

xxxxxBut his greatest failure in foreign affairs, and the one which brought him an immense amount of unpopularity, occurred during the First Anglo-Sudan War of 1884-1885. It was during this conflict that his government sent out General Charles Gordon to evacuate Egyptian garrisons in the Sudan, then being threatened by the Mahdi, rebel forces under the command of the fanatical leader Muhammad Ahmad. Gordon, who, together with other military leaders at this time, would have preferred to take the battle to the enemy, soon found that his garrison at Khartoum was completely surrounded by Mahdi forces. He frequently called for assistance, but Gladstone delayed sending a relief expedition. When, shamed into action by public outcry, he eventually did so, it failed in its mission. Led by General Lord Wolseley, it arrived two days too late in January 1885. Khartoum had fallen and Gordon had been killed. Gladstone’s handling of this affair was widely condemned. The press openly accused him of Gordon’s death, public opinion was openly hostile, and he received a rebuke from the Queen herself. The “Grand Old Man” (converted by Disraeli to “God’s Only Mistake”!) was twisted around to become the “Murderer of Gordon”. His government fell in the June.

xxxxxBut his greatest failure in foreign affairs, and the one which brought him an immense amount of unpopularity, occurred during the First Anglo-Sudan War of 1884-1885. It was during this conflict that his government sent out General Charles Gordon to evacuate Egyptian garrisons in the Sudan, then being threatened by the Mahdi, rebel forces under the command of the fanatical leader Muhammad Ahmad. Gordon, who, together with other military leaders at this time, would have preferred to take the battle to the enemy, soon found that his garrison at Khartoum was completely surrounded by Mahdi forces. He frequently called for assistance, but Gladstone delayed sending a relief expedition. When, shamed into action by public outcry, he eventually did so, it failed in its mission. Led by General Lord Wolseley, it arrived two days too late in January 1885. Khartoum had fallen and Gordon had been killed. Gladstone’s handling of this affair was widely condemned. The press openly accused him of Gordon’s death, public opinion was openly hostile, and he received a rebuke from the Queen herself. The “Grand Old Man” (converted by Disraeli to “God’s Only Mistake”!) was twisted around to become the “Murderer of Gordon”. His government fell in the June.

xxxxxSurprisingly perhaps, Gladstone survived this storm of protest, and was briefly back as prime minister in 1886, but, as we have seen, this period and his final years in power, 1892 to 1894, were mainly taken up by his attempts to obtain home rule for Ireland. When his second bill met with failure he resigned as prime minister in 1894, refused a title, and retired to Hawarden Castle, Flintshire, Wales, a country estate previously owned by his wife’s family. From here, true to form, he led a final crusade against the Armenian Massacres in 1896. He died of heart failure two years later, at the age of 88, and his body was conveyed on the London Transport for a state burial at Westminster Abbey. Among the pall bearers were the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII) and the Duke of York (the future George V).

xxxxxSurprisingly perhaps, Gladstone survived this storm of protest, and was briefly back as prime minister in 1886, but, as we have seen, this period and his final years in power, 1892 to 1894, were mainly taken up by his attempts to obtain home rule for Ireland. When his second bill met with failure he resigned as prime minister in 1894, refused a title, and retired to Hawarden Castle, Flintshire, Wales, a country estate previously owned by his wife’s family. From here, true to form, he led a final crusade against the Armenian Massacres in 1896. He died of heart failure two years later, at the age of 88, and his body was conveyed on the London Transport for a state burial at Westminster Abbey. Among the pall bearers were the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII) and the Duke of York (the future George V).

xxxxxGladstone failed in his two political ambitions - the abolition of the income tax and the settlement of the Irish question -, and his anti-imperialist views, at odds with the mood of his time, brought a measure of failure in his handling of foreign and colonial affairs. But this said, he played a dominate role in British politics throughout the latter part of the 19th century, and was a major force in shaping the Liberal Party. As such, he was active in the advancement of parliamentary reform, was a staunch advocate of sound finance, and he made an important contribution to the Reform Acts of 1867 and 1884. He was seen by his opponents as pompous and self-righteous - Queen Victoria dismissed him as “a half-crazy, ridiculous old man” - but throughout a long parliamentary career he pursued his aims with courage and conviction, and he ably used his skill as an orator to denounce crimes against humanity and to defend the virtues of peace.

xxxxxIncidentally, Gladstone’s fight to wi n his seat for the Scottish county of Midlothian in the election of 1880 is today regarded as the first pre-planned political campaign in British history. Using the newly developed railway system, he delivered a series of powerful, impassioned speeches across the country, taking to task the Conservatives’ policy at home, condemning their support of Turkey, and denouncing their colonial policy in the wars then being waged against the Zulus and the Afghans. It is estimated that by the end of his “Midlothian Campaign” close on 87,000 had heard him speak and each one of his speeches had been reported and discussed in the national press. As a result, the Liberals gained a landslide victory, and Gladstone was able to form a government for his second term as prime minister. ……

n his seat for the Scottish county of Midlothian in the election of 1880 is today regarded as the first pre-planned political campaign in British history. Using the newly developed railway system, he delivered a series of powerful, impassioned speeches across the country, taking to task the Conservatives’ policy at home, condemning their support of Turkey, and denouncing their colonial policy in the wars then being waged against the Zulus and the Afghans. It is estimated that by the end of his “Midlothian Campaign” close on 87,000 had heard him speak and each one of his speeches had been reported and discussed in the national press. As a result, the Liberals gained a landslide victory, and Gladstone was able to form a government for his second term as prime minister. ……

Xxxxx…… It was in 1876, during one of his periods in opposition, that Gladstone wrote his two major works: The Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East, a powerful condemnation of the atrocities committed by the Turkish Ottoman Empire upon its Christian subjects, and an erudite study of the Greek poet Homer entitled An Inquiry into the Time and Place of Homer in History. ……

Xxxxx…… Gladstone enjoyed a happy family life. His marriage to Catherine Glynne in 1839, the daughter of Sir Stephen Glynne of Hawarden, proved highly successful, and they had eight children. Catherine was an intelligent, charming women who supported her husband throughout his long career. ……

Xxxxx…… Thexcartoon above is by the Irish artist and illustrator Harry Furniss (1854-1925). He produced cartoons and drawings for a number of periodicals, including The Illustrated London News and Vanity Fair. He joined the staff of Punch in 1880, and it was there that he made his name as a political cartoonist. It is estimated that he produced more than 2,500 drawings for this satirical magazine.

xxxxxThe Third Reform Act of 1884, which was introduced and steered through the Commons by William Gladstone, extended the increase in franchise granted by the Second Reform Act of 1867. By it, agricultural labourers and other workers in rural areas were granted the same rights as male voters in the boroughs. The Bill was passed by the House of Commons but rejected by the Conservative-dominated House of Lords. However, Gladstone persisted, and after reintroducing the bill, gained the consent of the Lords by promising to introduce a Redistribution Bill - a change in constituency boundaries which was duly carried out in 1885.

xxxxxThe Act of 1884 increased the franchise by some eight million men, but all women and 40% of adult males still remained without the vote. It was not until 1918, at the end of the First World War, that men of 21 years and over were granted the right to vote. In the meantime a number of societies were established across the country demanding votes for women. In 1897 these were joined together to form the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Society, a lively organisation which doubtless played a part in sparking off the Suffragette Movement in the opening years of the new century. It was not until 1928, however, that women gained full equality with men.

xxxxxThe Act of 1884 increased the franchise by some eight million men, but all women and 40% of adult males still remained without the vote. It was not until 1918, at the end of the First World War, that men of 21 years and over were granted the right to vote. In the meantime a number of societies were established across the country demanding votes for women. In 1897 these were joined together to form the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Society, a lively organisation which doubtless played a part in sparking off the Suffragette Movement in the opening years of the new century. It was not until 1928, however, that women gained full equality with men.

xxxxxIncidentally, New Zealand was the first country in the world to give women the vote. As early as 1893 all women over the age of 21 were permitted to vote in parliamentary elections.

Including:

William Gladstone and

The Third Reform Act

xxxxxIt was the year after the Fenian Uprising of 1867 (Vb) -

xxxxxIt was the year after the Fenian Uprising of 1867 (Vb) - xxxxxThe First Irish Home Rule Bill was introduced in April 1886, and it was very much the work of Gladstone himself. He only had brief discussions with Parnell, and the complete draft was not discussed by cabinet until the last week in March. In broad terms, it proposed the establishment of an Irish legislature in Dublin made up of two orders -

xxxxxThe First Irish Home Rule Bill was introduced in April 1886, and it was very much the work of Gladstone himself. He only had brief discussions with Parnell, and the complete draft was not discussed by cabinet until the last week in March. In broad terms, it proposed the establishment of an Irish legislature in Dublin made up of two orders -

xxxxxThe year 1892 saw the fall of the Tories and Gladstone’s return to power. He at once set about the drawing up of the Second Irish Home Rule Bill. By that time Parnell was dead, but, as in the previous occasion, the prime minister sought little advice from others. As a result, the draft contained a number of errors -

xxxxxThe year 1892 saw the fall of the Tories and Gladstone’s return to power. He at once set about the drawing up of the Second Irish Home Rule Bill. By that time Parnell was dead, but, as in the previous occasion, the prime minister sought little advice from others. As a result, the draft contained a number of errors - xxxxxAs we have seen, the Liberal politician William Ewart Gladstone (1809-

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Liberal politician William Ewart Gladstone (1809- xxxxxIn home affairs he achieved a number of notable reforms, including competition for entry to the civil service, the introduction of state-

xxxxxIn home affairs he achieved a number of notable reforms, including competition for entry to the civil service, the introduction of state- xxxxxBut his greatest failure in foreign affairs, and the one which brought him an immense amount of unpopularity, occurred during the First Anglo-

xxxxxBut his greatest failure in foreign affairs, and the one which brought him an immense amount of unpopularity, occurred during the First Anglo- xxxxxSurprisingly perhaps, Gladstone survived this storm of protest, and was briefly back as prime minister in 1886, but, as we have seen, this period and his final years in power, 1892 to 1894, were mainly taken up by his attempts to obtain home rule for Ireland. When his second bill met with failure he resigned as prime minister in 1894, refused a title, and retired to Hawarden Castle, Flintshire, Wales, a country estate previously owned by his wife’s family. From here, true to form, he led a final crusade against the Armenian Massacres in 1896. He died of heart failure two years later, at the age of 88, and his body was conveyed on the London Transport for a state burial at Westminster Abbey. Among the pall bearers were the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII) and the Duke of York (the future George V).

xxxxxSurprisingly perhaps, Gladstone survived this storm of protest, and was briefly back as prime minister in 1886, but, as we have seen, this period and his final years in power, 1892 to 1894, were mainly taken up by his attempts to obtain home rule for Ireland. When his second bill met with failure he resigned as prime minister in 1894, refused a title, and retired to Hawarden Castle, Flintshire, Wales, a country estate previously owned by his wife’s family. From here, true to form, he led a final crusade against the Armenian Massacres in 1896. He died of heart failure two years later, at the age of 88, and his body was conveyed on the London Transport for a state burial at Westminster Abbey. Among the pall bearers were the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII) and the Duke of York (the future George V). n his seat for the Scottish county of Midlothian in the election of 1880 is today regarded as the first pre-

n his seat for the Scottish county of Midlothian in the election of 1880 is today regarded as the first pre- xxxxxThe Act of 1884 increased the franchise by some eight million men, but all women and 40% of adult males still remained without the vote. It was not until 1918, at the end of the First World War, that men of 21 years and over were granted the right to vote. In the meantime a number of societies were established across the country demanding votes for women. In 1897 these were joined together to form the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Society, a lively organisation which doubtless played a part in sparking off the Suffragette Movement in the opening years of the new century. It was not until 1928, however, that women gained full equality with men.

xxxxxThe Act of 1884 increased the franchise by some eight million men, but all women and 40% of adult males still remained without the vote. It was not until 1918, at the end of the First World War, that men of 21 years and over were granted the right to vote. In the meantime a number of societies were established across the country demanding votes for women. In 1897 these were joined together to form the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Society, a lively organisation which doubtless played a part in sparking off the Suffragette Movement in the opening years of the new century. It was not until 1928, however, that women gained full equality with men.