xxxxxAs we have

seen, the French poet, novelist and dramatist Victor Hugo produced

one of his best-known novels, The

Hunchback of Notre Dame in 1831

(W4). This, together with his many other

works made him the undisputed leader of the French romantic

movement. His most productive years were from 1830, but in 1843

the death of one of his daughters in a boating accident brought a

temporary stop to his writing. He served in the government of

Louis Philippe,

but by the time Napoleon III seized power in 1851 he was a

confirmed republican. He took refuge on the island of Guernsey,

and from there launched a scathing attack upon the “little

Napoleon” in both verse and prose. In 1862 he published his other famous novel, Les

Misérables, a story full of drama and pathos, set in the

Paris underworld of contemporary France.

This moving tale about social injustice

gave full scope to his remarkable powers of description and his

deep, sympathetic understanding of human nature. And also produced

during this period was some of his finest poetry - notably

his Les Contemplations -, and his

novels, Toilers of the Sea and The

Man Who Laughs, set in 17th century England. On his

return to France in 1870, following his country’s defeat in the

Franco-Prussian War, he was hailed as a national hero, and,

for a time, served in the Senate of the Third Republic. A notable

work in these later years was his Quatrevingt-treize,

a powerful novel describing the momentous events of the

year 1793. When he died in 1885 his

state funeral was attended by some two million people, such was

the esteem in which this great man of letters, republican hero,

and man of the people, was held.

VICTOR HUGO 1802 -

1885 (G3c, G4, W4,

Va, Vb, Vc)

Acknowledgements

Hugo: bronze bust

by the French sculptor August Rodin (1840-1917). 1883 – Musée

Rodin, Paris. Hauteville: date and

artist unknown. Misérables: based on an

original portrait of “Cosette” by the French illustrator Emile

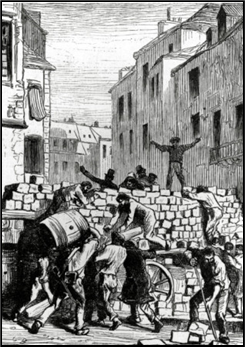

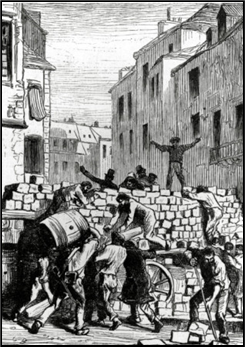

Bayard (1837-1891). Barricades:

illustration for Les Misérables by the

French artist Gustave Brion (1824-1877). Grandchildren: by the French photographer Achille Mélandri (1845-1905)

– Maison de Victor Hugo, Paris. Funeral:

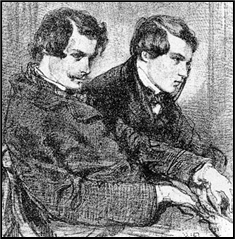

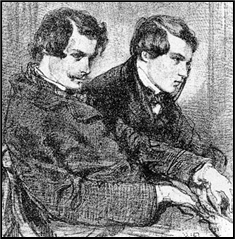

1885, photographer unknown. Goncourts:

drawing by the French illustrator Paul Gavarni (1804-1866)

and printed in 1853 by Lemercier et Cie, Paris publishers 1803-1909

– National Library of France, Paris. Verlaine:

by the French artist Eugène Carrière (1849-1906), 1890 –

Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Rimbaud: by the

French photographer Étienne Carjat (1828-1906), c1872.

xxxxxAs we have

seen, Victor Hugo, the French poet, novelist and dramatist,

produced one of his best-known novels, The

Hunchback of Notre Dame in 1831

(W4). This melodrama, together with

works such as his verse play Hanant and

his drama The King’s Fool, made him the

undisputed leader of the French romantic movement. Indeed, the

preface to his first play Cromwell,

produced in 1838, is regarded as the manifesto of Romanticism, or,

as he put it, “the liberation of literature”. Not for him the

literary restraints imposed by Classicism, a fact clearly shown in

the 1820s by his extravagant prose romances (such as Bug

Jagal) and his exotic poems, like his Orientales.

(The sculpture is by the famous French artist Auguste Rodin).

xxxxxHis most

productive period began in 1830 with his poetic drama Hernani,

a play which, as from its opening night, provided a long and

bitter controversy between the Romanticists and the Classicists.

The next thirteen years saw a stream of successful productions,

beginning with The Hunchback of Notre Dame,

and including the prose dramas Lucrece Borgia

and Marie Tudor, the melodrama Ruy

Blas, and several volumes of contemplative verse, such as

Songs of Twilight. These works in

particular showed his descriptive skill, his deep, sympathetic

understanding of human nature, and his masterly command of

language.

xxxxxBut the year 1843 was marred by disappointment and

sadness, brought about by the failure of his verse drama Les

Burgraves, and then the tragic death of one of his

daughters in a boating accident. Hugo was devastated, felt unable

to write, and turned to politics. A royalist at this juncture, he

accepted a post in the government of Louis Philippe in 1848, but

by the time Napoleon III had seized power in 1851 he was a

confirmed republican. As a result he was forced to flee the

country. In 1855, after taking refuge in Belgium and then the

island of Jersey in the Channel Islands, he eventually settled

down at St. Peter Port on the neighbouring island of Guernsey.

Hauteville House (illustrated) was to be his home until he returned to France in

1870 following the Franco-Prussian War and the fall of the

French Empire.

xxxxxBut the year 1843 was marred by disappointment and

sadness, brought about by the failure of his verse drama Les

Burgraves, and then the tragic death of one of his

daughters in a boating accident. Hugo was devastated, felt unable

to write, and turned to politics. A royalist at this juncture, he

accepted a post in the government of Louis Philippe in 1848, but

by the time Napoleon III had seized power in 1851 he was a

confirmed republican. As a result he was forced to flee the

country. In 1855, after taking refuge in Belgium and then the

island of Jersey in the Channel Islands, he eventually settled

down at St. Peter Port on the neighbouring island of Guernsey.

Hauteville House (illustrated) was to be his home until he returned to France in

1870 following the Franco-Prussian War and the fall of the

French Empire.

xxxxxOnce safe

in exile, Hugo wasted no time in denouncing the regime from

which he had fled. His pamphlets Napoléon le

Petit and Histoire d’un crime,

together with his collection of 97 poems entitled Les

Châtiments (The Punishments)

launched a scathing, intemperate attack upon the Second Empire in

general and Napoleon III in particular. The self-styled

Emperor was described as a man with blood on his hands, who lived

in splendour and cared nothing for the poverty and degradation

endured by the mass of his people.

xxxxxIn contrast, another collection of poems, Les

Contemplations of 1856, won acclaim for the simplicity

and purity of their tone, the beauty of their expression, and the

depth of their thought. Likewise his Legend of

the Centuries of 1859, a series of pictorial poems

illustrating man’s struggle between good and evil through the

ages, was well received. And later, as if to show the width of his

poetic powers, came Chansons des rues et des

bois (Songs of the streets and woods),

a collection of light, witty verse centred around his fleeting,

uncomplicated affairs with young maids and country girls. And also

belonging to this period was Les Travailleurs

de la Mer of 1866 (The Toilers of the

Sea), a passionate tale of man’s battle against the

waves, set appropriately in a Guernsey fishing community. Later

came an essay on William Shakespeare and The

Man Who Laughs, a novel set in 17th century England.

xxxxxIn contrast, another collection of poems, Les

Contemplations of 1856, won acclaim for the simplicity

and purity of their tone, the beauty of their expression, and the

depth of their thought. Likewise his Legend of

the Centuries of 1859, a series of pictorial poems

illustrating man’s struggle between good and evil through the

ages, was well received. And later, as if to show the width of his

poetic powers, came Chansons des rues et des

bois (Songs of the streets and woods),

a collection of light, witty verse centred around his fleeting,

uncomplicated affairs with young maids and country girls. And also

belonging to this period was Les Travailleurs

de la Mer of 1866 (The Toilers of the

Sea), a passionate tale of man’s battle against the

waves, set appropriately in a Guernsey fishing community. Later

came an essay on William Shakespeare and The

Man Who Laughs, a novel set in 17th century England.

xxxxxBut his major work while in exile was undoubtedly Les Misérables (The

Wretched), an historical prose romance which he had been

working on for many years and was eventually published in 1862.

A story about social injustice in contemporary, strife-ridden

France, it takes place for the most part in the Parisian

underworld - including, at one point, a dramatic flight

through the city’s sewers. It contains numerous plots, some only

broadly developed, and these are centred around the trials and

tribulations of Jean Valjean, a man who, having spent nineteen

years in prison - initially for stealing a loaf of bread -

gains a respectable position in society, but finds that he cannot

escape his past. Despite his good intentions, he is hounded by the

law in the person of police inspector Javert, and both meet their

deaths in the closing pages of the drama. The most endearing

character is Cosette, who, maltreated as a young girl, is cared

for by Valjean, and finally finds happiness with Marius Pontmercy,

a rebel who, like Hugo himself, becomes a republican in the cause

of freedom.

xxxxxBut his major work while in exile was undoubtedly Les Misérables (The

Wretched), an historical prose romance which he had been

working on for many years and was eventually published in 1862.

A story about social injustice in contemporary, strife-ridden

France, it takes place for the most part in the Parisian

underworld - including, at one point, a dramatic flight

through the city’s sewers. It contains numerous plots, some only

broadly developed, and these are centred around the trials and

tribulations of Jean Valjean, a man who, having spent nineteen

years in prison - initially for stealing a loaf of bread -

gains a respectable position in society, but finds that he cannot

escape his past. Despite his good intentions, he is hounded by the

law in the person of police inspector Javert, and both meet their

deaths in the closing pages of the drama. The most endearing

character is Cosette, who, maltreated as a young girl, is cared

for by Valjean, and finally finds happiness with Marius Pontmercy,

a rebel who, like Hugo himself, becomes a republican in the cause

of freedom.

xxxxxThis

panoramic view of French life, full of dramatic incident and

pathos, proved the perfect vehicle for Hugo’s remarkable powers of

description and his abiding sympathy for the poor and oppressed.

It contained, too, his own thoughts on religion, politics and

everyday affairs, together with some lengthy digressions, notably

his own account of the Battle of Waterloo. Received with

enthusiasm, the book earned him fame both at home and abroad.

xxxxxIn 1870,

with France having been defeated at the hands of the Prussians,

Hugo returned home a national hero, hailed as the man who had

waged a war of words against the Second Empire and helped to bring

about its downfall. He became a senator under the Third Republic,

but distress within his family took its toll. Having lost his wife

Adèle in 1868, the deaths of two of his sons and the mental

sickness of his daughter Adèle in the early 1870s sapped his

creative energy. In these final years, he wrote a number of

novels, several volumes of poetry, and a play, but in general they

lacked the master touch.

xxxxxHowever, this said, his last novel, Quatrevingt-treize,

produced in 1874 and graphically depicting the momentous events of

1793, is regarded by many today as one of his finest works, and by

some as his masterpiece. And worthy of note is his charming The Art of Being a Grandfather, published in

1877, and his four act drama Torquemada

of 1882, a play condemning religious fanaticism via the Spanish

Inquisition. During a life-time of writing Hugo produced

seven novels, 21 plays, and 18 volumes of poetry. (Hugo pictured here with his grandchildren).

xxxxxHowever, this said, his last novel, Quatrevingt-treize,

produced in 1874 and graphically depicting the momentous events of

1793, is regarded by many today as one of his finest works, and by

some as his masterpiece. And worthy of note is his charming The Art of Being a Grandfather, published in

1877, and his four act drama Torquemada

of 1882, a play condemning religious fanaticism via the Spanish

Inquisition. During a life-time of writing Hugo produced

seven novels, 21 plays, and 18 volumes of poetry. (Hugo pictured here with his grandchildren).

xxxxxIn 1878

Hugo suffered a rather severe stroke, but this did not stop Paris

from celebrating his eightieth year in unforgettable style. In one

of the largest parades ever held in the city, thousands upon

thousands of people walked down the Champs Élysées to the centre

of Paris, passing by his house in the Avenue d’Eylau (renamed

Victor Hugo that year), where he sat at one of the windows. It was

a rare and moving show of affection for a man of the people. He

died in 188 5,

two years after the death of his long-time mistress Juliette

Drouet. His body was laid in state beneath the Arc de Triomphe,

and then carried on a hearse down the Champs Élysées (illustrated) for burial in the

Panthéon. It is estimated that some two million people lined the

route to pay homage to the man who was not only one of France’s

greatest men of letters - a novelist and a poet of enormous

talent - but also a symbol for so many years of his country’s

struggle towards republicanism. He cared for the people and, at his

end, the people showed that they cared for him.

5,

two years after the death of his long-time mistress Juliette

Drouet. His body was laid in state beneath the Arc de Triomphe,

and then carried on a hearse down the Champs Élysées (illustrated) for burial in the

Panthéon. It is estimated that some two million people lined the

route to pay homage to the man who was not only one of France’s

greatest men of letters - a novelist and a poet of enormous

talent - but also a symbol for so many years of his country’s

struggle towards republicanism. He cared for the people and, at his

end, the people showed that they cared for him.

xxxxxIncidentally, having arrived in Paris in 1870, Hugo found himself

caught up in the siege of Paris. Later, in his poem L’Année

terrible, he described the suffering caused by that event

during what he called “the terrible year”. There was a severe

shortage of food but, as a celebrity, he was provided with meat

from the Paris zoo until supplies ran out. ……

xxxxx……xA number of operas were based on his works, including

Donizetti’s opera Lucrezia Borgia and

Verdi’s Rigoletto, and many of his

poems were set to music by Berlioz, Bizet, Saint-Saens,

Massenet and Wagner. He himself enjoyed music. He greatly admired

the works of Beethoven, and he liked the music of Gluck and Weber.

As noted earlier, he numbered among his literary friends  Lamartine,

Vigny, Musset, Mérimée and Gautier. ……

Lamartine,

Vigny, Musset, Mérimée and Gautier. ……

Xxxxx……xHis novel Toilers of the Sea,

written while in Guernsey, had an unexpected impact on social

behaviour. Its lurid account of strange creatures lurking in deep

waters made fashionable an interest in squids. Squid parties and

the wearing of squid hats became popular for a time! ……

xxxxx……xHugo has the distinction of providing the briefest

correspondence in history. After Les

Misérables was produced in 1862, he sent a letter to his

publisher to enquire as to its reception. The letter simply

contained a question mark. The publisher replied by a letter which

simply contained an exclamation mark! As indicated, the novel’s

success was immense, and became even more so towards the end of

the 20th century when it was adapted as a musical. It was first

staged in Paris in 1980 and opened in London five years later. It

was still running over twenty years later, and a film was made of

it in 2012. ……

xxxxx……xHugo was also a proficient ar tist

and during his lifetime produced more than 4,000 small-scale

drawings in brown or black pen and ink, many abstract in form.

These were praised by no less than Delacroix and Van Gogh.

Illustrated here is Town with a tumbledown

bridge. ……

tist

and during his lifetime produced more than 4,000 small-scale

drawings in brown or black pen and ink, many abstract in form.

These were praised by no less than Delacroix and Van Gogh.

Illustrated here is Town with a tumbledown

bridge. ……

……xIn St. Peter Port, Guernsey, Hauteville House, his

home for many years, is now a museum to his memory, and there is

an imposing statue of him in the Candie Gardens, overlooking the

harbour, the work of the Breton sculptor Jean Boucher in 1914. In

Paris his house on the Avenue Victor Hugo is also a museum, and a

square and metro station are also named after him. Needless to

say, there is hardly a town in France that does not have a street

named in his honour.

Including:

The Goncourt Brothers,

Paul

Verlaine and

Arthur Rimbaud

xxxxxThe French Goncourt Brothers, Edmond

(1822-1896) and Jules (1830-1870), wrote a number of

works together, including a study of French society and art during

the 18th century, and six novels. Notable among their

fiction were Germinie Lacerteux and Madame Gervaisais, works which marked them

out as pioneers in naturalism - exposing in blunt terms the

harsh, sordid side of life. They also collaborated in the writing

of a personal Journal. This brutally

frank account of the social and literary life of Paris from 1851

to 1896 was full of gossip, anecdotes and criticism of the leading

celebrities of the day. At his death Edmond bequeathed his estate

to the founding of the Académie Goncourt

and from 1903 this has awarded the Prix

Goncourt to the best French fiction writer of the year.

xxxxxThe French Goncourt

Brothers, Edmond (1822-1896) and

Jules (1830-1870), began working together as watercolour

artists in the 1850s, but they then turned their attention to

social history and art criticism. Their detailed study of French

society and French art during the 18th century was remarkable for

the thoroughness of their research, and was generally well

received. However, success was less marked when they collaborated

in the writing of six novels. In this field they were working in

the shadow of the great Émile Zola. Nonetheless, as realistic

novelists like him, they were pioneers in naturalism, exposing in

blunt terms the harsh, sordid side of life. Two of their works are

especially worthy of mention. Germinie

Lacerteux, published in 1865, depicted the miserable life

led by the lower classes - very much in the Hugo mould in

that respect - and Madame Gervaisais,

produced four years later, was another story of degradation, woven

around religious mania.

xxxxxThe French Goncourt

Brothers, Edmond (1822-1896) and

Jules (1830-1870), began working together as watercolour

artists in the 1850s, but they then turned their attention to

social history and art criticism. Their detailed study of French

society and French art during the 18th century was remarkable for

the thoroughness of their research, and was generally well

received. However, success was less marked when they collaborated

in the writing of six novels. In this field they were working in

the shadow of the great Émile Zola. Nonetheless, as realistic

novelists like him, they were pioneers in naturalism, exposing in

blunt terms the harsh, sordid side of life. Two of their works are

especially worthy of mention. Germinie

Lacerteux, published in 1865, depicted the miserable life

led by the lower classes - very much in the Hugo mould in

that respect - and Madame Gervaisais,

produced four years later, was another story of degradation, woven

around religious mania.

xxxxxMore enduring in time and value, however, were the

nine volumes of their personal Journal,

begun in 1851 and kept up to within twelve days of Edmond’s death

in July 1896. Providing a detailed peepshow of social and literary

life in Paris during the “belle époque”, it was full of gossip,

anecdotes and cruel criticism of friend and foe alike. Among the

many who suffered from their barbs were the writers Hugo,

Flaubert, Baudelaire and Zola, the artist Degas, and the sculptor

Rodin. Few if any daily chronicles of society have been so

colourful, so vengeful and so brutally frank. Both brothers considered that their work was not appreciated

enough, and this doubtless accounts for the strength and scope of

their invective.

xxxxxMore enduring in time and value, however, were the

nine volumes of their personal Journal,

begun in 1851 and kept up to within twelve days of Edmond’s death

in July 1896. Providing a detailed peepshow of social and literary

life in Paris during the “belle époque”, it was full of gossip,

anecdotes and cruel criticism of friend and foe alike. Among the

many who suffered from their barbs were the writers Hugo,

Flaubert, Baudelaire and Zola, the artist Degas, and the sculptor

Rodin. Few if any daily chronicles of society have been so

colourful, so vengeful and so brutally frank. Both brothers considered that their work was not appreciated

enough, and this doubtless accounts for the strength and scope of

their invective.

xxxxxEdmond, who

outlived his brother by over twenty-five years, went on to

produce his own novels - notably La Fille

Élisa and Chérie -, and

he did eventually ensure that the name of Goncourt lived on. Whenxhe died he bequeathed his entire estate for the

founding of the Goncourt

Academy. Since

1903 this has awarded the Prix Goncourt

- the most prestigious award in French literature - to

the author of “the best imaginary prose work of the year”.

xxxxxAnother

important French poet of this period was Paul

Verlaine (1844-1896). At the age of

14 he sent his first poem, La Mort, to

Victor Hugo. He gained fame with his Poèmes

Saturniens of 1866, and during his career produced Fêtes galantes, La Bonne

Chanson, Romances sans paroles

and Sagesse. His poetry, inspired by

unconscious forces such as dreams, imagination and delirium,

marked him out as the leader of the early Symbolists. His ideas

were summarized in his L’Art poétique of

1884. In his private life, his torrid love affair with the young

poet Arthur Rimbaud ended in violence in 1873 and two years in

prison. In his later years he took to drink and drugs, and lived

in poverty, but his contribution to poetry was recognised. In the

mid-1880s he drew attention to the work of Rimbaud, and

published some of the young poet’s verse. These were well received

and put Rimbaud at the head of a new literary movement.

xxxxxAnd another outstanding French poet of this period

was Paul Verlaine

(1844-1896). At the age of 14 he sent his first poem, La Mort, to the great Victor Hugo. His Poèmes saturniens of 1866, noted for their

musical quality and delicate harmonies, marked him out as a poet

of promise, but his degenerate private life impeded his progress.

In 1872 he abandoned his wife and young child to live with the

young poet Arthur Rimbaud. Their love affair, however, was a very

stormy and debauched one, and ended the following year when,

during a violent quarrel, Verlaine shot Rimbaud in the hand. He

was sentenced to two years in prison for attempted murder ,and it

was after this, while teaching in England in 1880, that he

produced Sagesse, a selection of

successful poems inspired by his conversion to Roman Catholicism.

xxxxxAnd another outstanding French poet of this period

was Paul Verlaine

(1844-1896). At the age of 14 he sent his first poem, La Mort, to the great Victor Hugo. His Poèmes saturniens of 1866, noted for their

musical quality and delicate harmonies, marked him out as a poet

of promise, but his degenerate private life impeded his progress.

In 1872 he abandoned his wife and young child to live with the

young poet Arthur Rimbaud. Their love affair, however, was a very

stormy and debauched one, and ended the following year when,

during a violent quarrel, Verlaine shot Rimbaud in the hand. He

was sentenced to two years in prison for attempted murder ,and it

was after this, while teaching in England in 1880, that he

produced Sagesse, a selection of

successful poems inspired by his conversion to Roman Catholicism.

xxxxxHe returned

to France in 1877, and it was while working as a teacher at Rethel

in north-eastern France that he became infatuated with one of

his pupils, Lucien Letinois. This liaison inspired Verlaine to

write more poetry, but his young lover’s sudden death through

typhus in 1883 was a blow from which he never really recovered. In

his final years he took to drink and drugs, and ended up poverty

stricken, but his peers recognised the originality of his work and

elected him France’s “Prince of Poets” two years before his death.

xxxxxVerlaine

was a leader of the early Symbolists, his inspiration moulded by

unconscious forces such as dreams, imagination and delirium, and

captured through the magic of words and the cadence of verse. The

nature of his poetry - which is difficult if not impossible

to translate - was summed up in his L’art

Poétique in 1884. Other major works included Fêtes

galantes (inspired by the paintings of Watteau), La

Bonne Chanson and Romances sans

paroles, verses composed whilst in prison. His

autobiographical prose, - My Hospitals, My Prisons

and Confessions - was all written

in the 1890s. In the mid-1880s he drew attention to the work

of Rimbaud in his Accursed Poets, and

published some of the young poet’s verse, including his prose

poems Illuminations. These were well

received and established Rimbaud at the head of a new literary

movement.

xxxxxThe French

composer Gabriel Fauré set many of Verlaine’s poems to music, and

Claude Debussy put music to five of his poems from Fêtes

galantes as part of his collection entitled Récueil

Vasnier.

xxxxxThe violent

quarrel with Paul Verlaine in 1873 virtually put an end to the

poetic career of the young French poet Arthur

Rimbaud (1854-1891). A precursor of

surrealism, he saw the poet as a seer who, by a long “derailment

of all the senses” would come to know the unknown and would let

his visions be seen through his verse. His major poems, all

written before the age of twenty, included Letters

of the Voyant (in which he sets out his poetic doctrine),

The Drunken Ship, A

Season in Hell - an account of his torrid love

affair with Verlaine -, and his cycle of prose poems entitled

Illuminations. After the break with

Verlaine he travelled extensively in Europe and the Middle East,

but was taken ill with cancer in 1891, and died at the age of

thirty-seven. In the meantime, however, the publication of a

number his poems by Verlaine in the mid-1880s brought him

fame at home, where he was seen as the leader of a new literary

movement.

xxxxxThe violent quarrel with Paul Verlaine in 1873

virtually put an end to the poetic career of Arthur

Rimbaud (1854-1891). Troubled and

restless, he chose to live the life of a nomad. He travelled

extensively in Europe, mostly on foot, and then, as a member of

the Dutch colonial army, spent some time in Java. After this, he

took up various jobs in Cyprus and Aden before working as a

merchant in Harar in eastern Ethiopia. It was there that he was

taken ill. He returned to France in 1891 and died of cancer in the

November, just a month after his 37th birthday. In the meantime,

however, Verlaine published a number of his poems in the mid-1880s

- including his prose poems Illuminations

- and these brought him fame at home, where he was seen as

the leader of a new literary genre.

xxxxxThe violent quarrel with Paul Verlaine in 1873

virtually put an end to the poetic career of Arthur

Rimbaud (1854-1891). Troubled and

restless, he chose to live the life of a nomad. He travelled

extensively in Europe, mostly on foot, and then, as a member of

the Dutch colonial army, spent some time in Java. After this, he

took up various jobs in Cyprus and Aden before working as a

merchant in Harar in eastern Ethiopia. It was there that he was

taken ill. He returned to France in 1891 and died of cancer in the

November, just a month after his 37th birthday. In the meantime,

however, Verlaine published a number of his poems in the mid-1880s

- including his prose poems Illuminations

- and these brought him fame at home, where he was seen as

the leader of a new literary genre.

xxxxxRimbaud was

born in Charleville in the Ardennes, north-eastern France,

and was brought up under the guidance of a tyrannical mother. He

was a precocious child - Victor Hugo

called him “un enfant Shakespeare” -

but the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 put an

end to his formal education. It was then that he rebelled against

his strict upbringing. He joined the National Guard for a short

period of time, and then took to the road, living rough, despising

conventional society, and enjoying his new-found freedom. His

behaviour became outlandish and some of his verse was

provocatively obscene.

xxxxxHis serious compositions during this period, such as

his Sensation and Ophelia,

were fairly conventional in form and much in the style of

Baudelaire, but by May 1871, fired by the revolution taking place

in Paris - the Commune - he had dismissed traditional

poetic form and was drawing up his own manifesto for a revolution

based on a poetic mould that was freed from all influences. In his

Lettres du voyant of 1871, he declared that the poet must become

a seer by means of “a long, immense and calculated derailment of

all the senses”. Then, as the supreme “Savant”, he would come to

know the unknown - that which lay beneath the surface of so-called

reality - and he could then let his visions be seen through

his verse. Poetry would not merely set actions to rhythms, but

would itself take action and assume the lead. His Le

Bateau ivre (The Drunken Boat),

composed soon afterwards, was a visionary piece, full of imagery

and metaphors, which demonstrated his avant-garde doctrine.

It came to be seen as a precursor of surrealism.

xxxxxHis serious compositions during this period, such as

his Sensation and Ophelia,

were fairly conventional in form and much in the style of

Baudelaire, but by May 1871, fired by the revolution taking place

in Paris - the Commune - he had dismissed traditional

poetic form and was drawing up his own manifesto for a revolution

based on a poetic mould that was freed from all influences. In his

Lettres du voyant of 1871, he declared that the poet must become

a seer by means of “a long, immense and calculated derailment of

all the senses”. Then, as the supreme “Savant”, he would come to

know the unknown - that which lay beneath the surface of so-called

reality - and he could then let his visions be seen through

his verse. Poetry would not merely set actions to rhythms, but

would itself take action and assume the lead. His Le

Bateau ivre (The Drunken Boat),

composed soon afterwards, was a visionary piece, full of imagery

and metaphors, which demonstrated his avant-garde doctrine.

It came to be seen as a precursor of surrealism.

xxxxxIn August

1871 Rimbaud sent examples of his new poetry to Verlaine, and this

led to their meeting and their torrid love affair. This came to a

tragic finale in 1873 and, by the following year, it had also

brought an end to his career as a poet. In was then that he took

to a wandering life. His other major works, all composed before

the age of twenty, were Une Saison en Enfer

(A Season in Hell) - an account of

his troubled life with Verlaine - and his Illuminations,

a cycle of prose poems, some of which were written during visits

he and Verlaine made to London in late 1872 and early 1873.

Vb-1862-1880-Vb-1862-1880-Vb-1862-1880-Vb-1862-1880-Vb-1862-1880-Vb-1862-1880-Vb

xxxxxBut the year 1843 was marred by disappointment and

sadness, brought about by the failure of his verse drama Les

Burgraves, and then the tragic death of one of his

daughters in a boating accident. Hugo was devastated, felt unable

to write, and turned to politics. A royalist at this juncture, he

accepted a post in the government of Louis Philippe in 1848, but

by the time Napoleon III had seized power in 1851 he was a

confirmed republican. As a result he was forced to flee the

country. In 1855, after taking refuge in Belgium and then the

island of Jersey in the Channel Islands, he eventually settled

down at St. Peter Port on the neighbouring island of Guernsey.

Hauteville House (illustrated) was to be his home until he returned to France in

1870 following the Franco-

xxxxxBut the year 1843 was marred by disappointment and

sadness, brought about by the failure of his verse drama Les

Burgraves, and then the tragic death of one of his

daughters in a boating accident. Hugo was devastated, felt unable

to write, and turned to politics. A royalist at this juncture, he

accepted a post in the government of Louis Philippe in 1848, but

by the time Napoleon III had seized power in 1851 he was a

confirmed republican. As a result he was forced to flee the

country. In 1855, after taking refuge in Belgium and then the

island of Jersey in the Channel Islands, he eventually settled

down at St. Peter Port on the neighbouring island of Guernsey.

Hauteville House (illustrated) was to be his home until he returned to France in

1870 following the Franco- xxxxxIn contrast, another collection of poems, Les

Contemplations of 1856, won acclaim for the simplicity

and purity of their tone, the beauty of their expression, and the

depth of their thought. Likewise his Legend of

the Centuries of 1859, a series of pictorial poems

illustrating man’s struggle between good and evil through the

ages, was well received. And later, as if to show the width of his

poetic powers, came Chansons des rues et des

bois (Songs of the streets and woods),

a collection of light, witty verse centred around his fleeting,

uncomplicated affairs with young maids and country girls. And also

belonging to this period was Les Travailleurs

de la Mer of 1866 (The Toilers of the

Sea), a passionate tale of man’s battle against the

waves, set appropriately in a Guernsey fishing community. Later

came an essay on William Shakespeare and The

Man Who Laughs, a novel set in 17th century England.

xxxxxIn contrast, another collection of poems, Les

Contemplations of 1856, won acclaim for the simplicity

and purity of their tone, the beauty of their expression, and the

depth of their thought. Likewise his Legend of

the Centuries of 1859, a series of pictorial poems

illustrating man’s struggle between good and evil through the

ages, was well received. And later, as if to show the width of his

poetic powers, came Chansons des rues et des

bois (Songs of the streets and woods),

a collection of light, witty verse centred around his fleeting,

uncomplicated affairs with young maids and country girls. And also

belonging to this period was Les Travailleurs

de la Mer of 1866 (The Toilers of the

Sea), a passionate tale of man’s battle against the

waves, set appropriately in a Guernsey fishing community. Later

came an essay on William Shakespeare and The

Man Who Laughs, a novel set in 17th century England. xxxxxBut his major work while in exile was undoubtedly Les Misérables (The

Wretched), an historical prose romance which he had been

working on for many years and was eventually published in 1862.

A story about social injustice in contemporary, strife-

xxxxxBut his major work while in exile was undoubtedly Les Misérables (The

Wretched), an historical prose romance which he had been

working on for many years and was eventually published in 1862.

A story about social injustice in contemporary, strife-

xxxxxHowever, this said, his last novel, Quatrevingt-

xxxxxHowever, this said, his last novel, Quatrevingt- 5,

two years after the death of his long-

5,

two years after the death of his long- Lamartine,

Vigny, Musset, Mérimée and Gautier.

Lamartine,

Vigny, Musset, Mérimée and Gautier.  tist

and during his lifetime produced more than 4,000 small-

tist

and during his lifetime produced more than 4,000 small-

xxxxxThe French Goncourt

Brothers, Edmond (1822-

xxxxxThe French Goncourt

Brothers, Edmond (1822- xxxxxMore enduring in time and value, however, were the

nine volumes of their personal Journal,

begun in 1851 and kept up to within twelve days of Edmond’s death

in July 1896. Providing a detailed peepshow of social and literary

life in Paris during the “belle époque”, it was full of gossip,

anecdotes and cruel criticism of friend and foe alike. Among the

many who suffered from their barbs were the writers Hugo,

Flaubert, Baudelaire and Zola, the artist Degas, and the sculptor

Rodin. Few if any daily chronicles of society have been so

colourful, so vengeful and so brutally frank. Both brothers considered that their work was not appreciated

enough, and this doubtless accounts for the strength and scope of

their invective.

xxxxxMore enduring in time and value, however, were the

nine volumes of their personal Journal,

begun in 1851 and kept up to within twelve days of Edmond’s death

in July 1896. Providing a detailed peepshow of social and literary

life in Paris during the “belle époque”, it was full of gossip,

anecdotes and cruel criticism of friend and foe alike. Among the

many who suffered from their barbs were the writers Hugo,

Flaubert, Baudelaire and Zola, the artist Degas, and the sculptor

Rodin. Few if any daily chronicles of society have been so

colourful, so vengeful and so brutally frank. Both brothers considered that their work was not appreciated

enough, and this doubtless accounts for the strength and scope of

their invective.

xxxxxAnd another outstanding French poet of this period

was Paul Verlaine

(1844-

xxxxxAnd another outstanding French poet of this period

was Paul Verlaine

(1844-

xxxxxThe violent quarrel with Paul Verlaine in 1873

virtually put an end to the poetic career of Arthur

Rimbaud (1854-

xxxxxThe violent quarrel with Paul Verlaine in 1873

virtually put an end to the poetic career of Arthur

Rimbaud (1854- xxxxxHis serious compositions during this period, such as

his Sensation and Ophelia,

were fairly conventional in form and much in the style of

Baudelaire, but by May 1871, fired by the revolution taking place

in Paris -

xxxxxHis serious compositions during this period, such as

his Sensation and Ophelia,

were fairly conventional in form and much in the style of

Baudelaire, but by May 1871, fired by the revolution taking place

in Paris -