xxxxxAs we have seen, the Greeks gained their independence after staging a major revolt against Turkish rule in 182l (G4). However, to the north large numbers of Greeks still remained within the Ottoman Empire, and it was not until the Berlin Congress of 1878, which drew up the settlement at the end of the Russo-

THE GRECO-

Acknowledgements

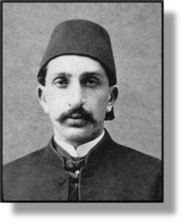

Map (Greece): licensed under Creative Commons – www.thefullwiki.com. Map (Crete): A postcard, date unknown. Considered to be in the public domain – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ottoman+Empire. Map (The Balkans): from www. worldology.com/Europe/Europe_Nations. Hamid II: detail, by the Abdullah Frères (active 1858-

xxxxxBut the Greece of those days (see map above) was only the southern extremity of the peninsula, together with some 30 islands in the Aegean Sea. To the north a large Greek population still lived under Ottoman rule, a fact that gave rise to the Megali Idea (Great Idea), aimed at uniting all Greeks under a single territory. Under its first monarch, a Bavarian prince named Otto, appointed by the Great Powers (Britain, France and Russia) in 1832, Greece made little progress in that direction. In 1862, however, he was deposed, and his successor, a Danish prince named George, proved anxious to unite the Greek people. A start was made in 1864 when the British, as a gesture of good will to the new monarch, transferred to Greece the seven Ionian Islands situated off its west coast (arrowed on map). Then throughout the 1870s pressure was put on the Ottoman Empire to cede Epirus and Thessaly, and this demand was intensified during the Russo-

xxxxxThe next opportunity to expand came in 1897 following further clashes between Muslims and Christians on the Island of Crete. Part of the Ottoman Empire since 1669, there had been frequent uprisings to overthrow Turkish rule, notably during the Greek fight for independence in the early 1820s and in 1841,1858 and the late 1860s. Despite the ferocity of these rebellions, however, all had failed. But in 1897 violence again broke out across the island, accompanied by a massacre of Christians in the coastal towns of Chania and Rethymno. The Great Powers (Britain, France, Italy and Russia) were anxious to prevent the trouble spreading, and prepared to intervene, but they proved too late. The Greek government, goaded by public opinion, quickly sent a force of some 1,500 men to defend the Greek community. This landed at Kolymbari at the beginning of February with the declared aim of taking over the island and uniting it with Greece. When a contingent from the Great Powers eventually arrived, they stopped the Greek force from approaching Chania, and then blockaded the island to prevent the landing of any more troops.

xxxxxThe next opportunity to expand came in 1897 following further clashes between Muslims and Christians on the Island of Crete. Part of the Ottoman Empire since 1669, there had been frequent uprisings to overthrow Turkish rule, notably during the Greek fight for independence in the early 1820s and in 1841,1858 and the late 1860s. Despite the ferocity of these rebellions, however, all had failed. But in 1897 violence again broke out across the island, accompanied by a massacre of Christians in the coastal towns of Chania and Rethymno. The Great Powers (Britain, France, Italy and Russia) were anxious to prevent the trouble spreading, and prepared to intervene, but they proved too late. The Greek government, goaded by public opinion, quickly sent a force of some 1,500 men to defend the Greek community. This landed at Kolymbari at the beginning of February with the declared aim of taking over the island and uniting it with Greece. When a contingent from the Great Powers eventually arrived, they stopped the Greek force from approaching Chania, and then blockaded the island to prevent the landing of any more troops.

xxxxxIn the meantime, however, the Ottoman Empire, in response to this “invasion”, stationed a large army along its border with Thessaly. The Greek government then reinforced its own border defences, simply as a show of strength, but an irregular force took matters into its own hands. Supported in particular by the Ethnike Etairia, a secret society dedicated to the liberation of all Greek people, it crossed the border in April 1897 and attacked a number of Turkish outposts in Macedonia. The Ottoman Empire at once declared war upon Greece, and the brief conflict which followed spelled disaster for the Greeks. Heavily outnumbered and ill-

xxxxxBy the armistice terms, completed in 1898, Greece lost some land to Turkey along the northern border of Thessaly, and was obliged to pay a large indemnity, adding further to its substantial foreign debt. At the same time, Turkey was made to withdraw all its forces from Crete, and Prince George, the second son of George I, was appointed high commissioner of the independent Cretan State, under the protection of the European powers. But this settlement, seen at the time as a workable solution, proved unacceptable. Over the next ten years protest continued across the island, and in 1908 the Cretan assembly declared union with Greece. The Great Powers eventually accepted this action and withdrew their forces, but it was not recognised internationally until 1913, following the Balkan Wars. By the Treaty of London in that year, the Ottoman Empire relinquished all rights over the island, and the Greek flag was raised at the Firkas fortress at Chania.

xxxxxAnd it was these Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913 that finally saw the expansion of Greek sovereignty to the north. In 1912, following their defeat by an alliance of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro, the Turks relinquished not only their claim to Crete, but also to all their European territories save for a small area around Istanbul. This settlement gave Greece control of southern Epirus. Then the second conflict of 1913 in which Bulgaria was defeated by Greece and Serbia almost doubled the size of Greece. By the Treaty of Bucharest in 1914, the Greeks took control of the whole of Macedonia and part of Thrace, including Salonika.

xxxxxBut if the latter part of 19th century and the opening years of the 20th saw the territorial growth of Greece (despite its domestic instability and the severe defeat it suffered at the hands of the Ottoman Empire), it also witnessed the gradual collapse of Turkey, the sick man of Europe. The Turkish Sultan Abdul Hamid II, in power from 1876 to 1909, presided over a period of marked decline in the extent and power of his empire. As a result of the Russo-

xxxxxBut if the latter part of 19th century and the opening years of the 20th saw the territorial growth of Greece (despite its domestic instability and the severe defeat it suffered at the hands of the Ottoman Empire), it also witnessed the gradual collapse of Turkey, the sick man of Europe. The Turkish Sultan Abdul Hamid II, in power from 1876 to 1909, presided over a period of marked decline in the extent and power of his empire. As a result of the Russo-

xxxxxLoses continued into the 20th century. Abdul Hamid’s successor in 1909, Mehmed V, saw the loss of virtually all his European territories following the defeat of Turkey in the Balkan War of 1912. He died in 1918 and was thus spared the humiliation of seeing the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire in 1922, an empire which, at the height of its power in the 17th century, included present-

xxxxxIncidentally, the Greco- s Black 97 -

s Black 97 -

xxxxx…… As we have seen, it was Abdul Hamid II (illustrated) who carried out the Armenian Massacres, a brutal repression of a Christian people during his campaign of ethnic cleansing from 1894 to 1896. Later an even more vicious campaign of extermination was waged against the Armenians during the First World War.

Vc-

Including:

The Island

of Crete

xxxxxAs we have seen, it was in 1821 (G4) that the Greeks staged a major revolt against Turkish rule. At first they met with little success. The Egyptian leader Muhammad Ali, wooed by the promise of territorial gains (including the island of Crete), sent an army to assist the Sultan, and quickly occupied the southern provinces of Greece. However, in 1827 Russia, Britain and France, alarmed at the situation, recognised Greek independence and destroyed a Turco-