EDWARD GIBBON 1737 -

xxxxxThe English historian Edward Gibbon is famous for his History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. The six volumes, completed in 1788, are noted for their width of coverage, degree of accuracy, and the elegance and clarity of their style. He decided to write the history after a visit to Rome in 1763, “musing amidst the ruins of the Capitol”. The work, which was not without its critics, covers the empires of both Rome and Constantinople. He was a member of parliament for twelve years and numbered among his friends Joshua Reynolds, James Boswell and Oliver Goldsmith.

xxxxxThe name of the English historian Edward Gibbon is inextricably linked with his monumental work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Published in six volumes and completed in 1788, it is an outstanding work for its width of coverage, degree of accuracy, and the elegance and clarity of its style.

xxxxxThe name of the English historian Edward Gibbon is inextricably linked with his monumental work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Published in six volumes and completed in 1788, it is an outstanding work for its width of coverage, degree of accuracy, and the elegance and clarity of its style.

xxxxxGibbon was born into a wealthy middle-

xxxxxGibbon was born into a wealthy middle-

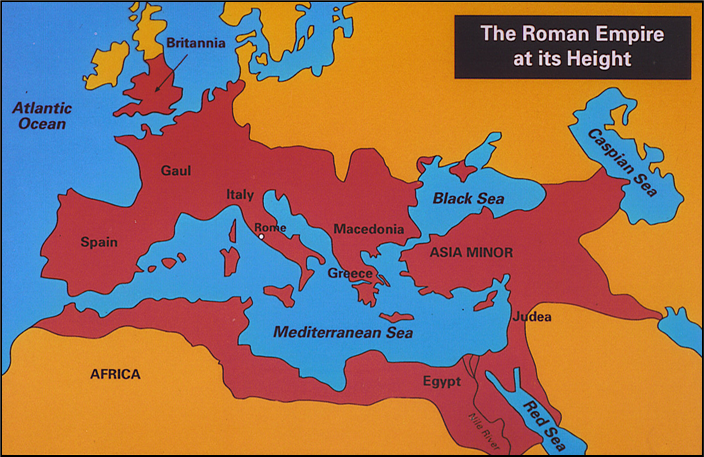

xxxxxThe Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire traces the history, in fact, of two empires, that of Rome in the west, and that of Constantinople, its successor, in the east -

xxxxxThe Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire traces the history, in fact, of two empires, that of Rome in the west, and that of Constantinople, its successor, in the east -

Acknowledgements

Gibbon, by the English portrait painter Joshua Reynolds (1723-

Including:

The Paston Letters

and Hannah More

xxxxxIt was in this year (1788) that the English philanthropist Hannah More (1745-

xxxxxAnd it was in this year (1788) that the English philanthropist Hannah More published her Thoughts on the Importance of the Manner of the Great General Society, a powerful defence of traditional values, produced at a time when a spiralling revolt was threatening to tear to pieces the social fabric in France.

xxxxxAnd it was in this year (1788) that the English philanthropist Hannah More published her Thoughts on the Importance of the Manner of the Great General Society, a powerful defence of traditional values, produced at a time when a spiralling revolt was threatening to tear to pieces the social fabric in France.

xxxxxMore was born near Bristol, England, in 1745. Seeking a career in writing, she wrote her pastoral drama, The Search After Happiness, at the age of 18, and paid her first visit to London in 1773. There she joined the circle of Blue Stockings, and became acquainted with Samuel Johnson, Joshua Reynolds and the radical politician Edmund Burke. And it was through her friendship with the actor David Garrick that her two plays The Inflexible Captive and Percy were performed. In the 1780s, however, she abandoned her stage career and, being religious by nature, turned her attention to good works. She opened up Sunday schools and clubs for women in her home county, Somerset, and, with the help of others, began producing a series of religious tracts, advising the poor to live a sober, hard-

xxxxxHer other works included Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education, produced in 1799, her novel Coelebs in Search of a Wife, published in 1808, and her religious tract The Shepherd of Salisbury Plain. She died in 1833, leaving all her money to charitable and religious institutions.

xxxxxHer other works included Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education, produced in 1799, her novel Coelebs in Search of a Wife, published in 1808, and her religious tract The Shepherd of Salisbury Plain. She died in 1833, leaving all her money to charitable and religious institutions.

xxxxxAndxworthy of mention at this time (1789) is the publication of The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne by the English naturalist Gilbert White (1720-

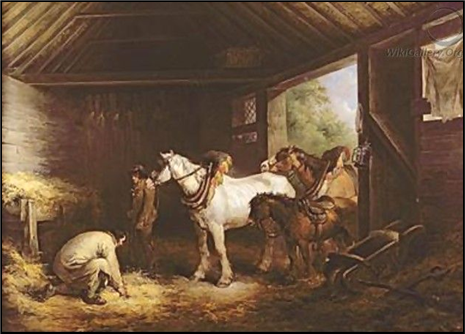

xxxxxAndxpaintings depicting sentimental rustic scenes of this period were produced by the English artist George Morland (1763-

xxxxxAndxpaintings depicting sentimental rustic scenes of this period were produced by the English artist George Morland (1763-

xxxxxAlthough fully committed to his marathon task, Gibbon found time to live the life of an English gentleman, and to take part in London’s social life. He joined the fashionable London clubs, including the one which met at the Turk’s Head -

xxxxxIt must be said that, as an individual, he was not prepossessing in his later years. Obese, short of build, and with a liking for gaudy clothes, he was often the butt of ridicule among London’s fashionable society. Nevertheless many admired his clear, sharp mind -

xxxxxIncidentally, it was during his first stay in Lausanne that Gibbon met and fell in love with Suzanne Churchod, a pastor’s daughter, the only love of his life. His father, however, would not hear of this “strange alliance”, and he was forced to give her up. He later wrote in his Memoirs, “I sighed as a lover, I obeyed as a son”. However, he and Suzanne remained lifelong friends, and she became the wife of Jacques Necker, the financial minister to Louis XVI. ……

xxxxx…… Betweenx1769 and 1772 a series of powerful satirical pieces were published in London under the title “Letters of Junius”. Extremely witty and spitefully scathing, they roundly denounced the government of George III, taking to task a number of his ministers, including the prime minister Lord North, and lampooning the King himself. A large number of writers were then put forward as the Junius in question, and Edward Gibbon was included among them, together with other eminent figures, such as Edmund Burke and Thomas Paine. The author was never discovered, but it is now believed that it was Sir Philip Francis, then serving as a clerk in the War Office.

xxxxx…… Betweenx1769 and 1772 a series of powerful satirical pieces were published in London under the title “Letters of Junius”. Extremely witty and spitefully scathing, they roundly denounced the government of George III, taking to task a number of his ministers, including the prime minister Lord North, and lampooning the King himself. A large number of writers were then put forward as the Junius in question, and Edward Gibbon was included among them, together with other eminent figures, such as Edmund Burke and Thomas Paine. The author was never discovered, but it is now believed that it was Sir Philip Francis, then serving as a clerk in the War Office.

xxxxxIt was at this time (1787 to 1789) that four volumes of the Paston Letters were being edited and published by James Fenn of Dereham, Norfolk. The letters relate to the life of a Norfolk family during the 15th century. The collection, made up of more than 1,000 items and including legal records, news articles and local gossip, throw an interesting light upon the conditions of the day. It is not known how the letters came to survive, but they were discovered by a certain Francis Blomefield when he was exploring the family home at Oxnead in 1735. He kept those he thought of historical value, and they ended up in the British Museum and the Bodleian Library at Oxford. A fifth volume was published by a William Frere in 1823, and the whole collection, entitled The Paston Letters and covering the years 1422 to 1509, was re-

xxxxxIt was at this time (1787 to 1789) that four volumes of the Paston Letters were being edited and published by James Fenn of Dereham, Norfolk. The letters relate to the life of a Norfolk family during the 15th century. The collection, made up of more than 1,000 items and including legal records, news articles and local gossip, throw an interesting light upon the conditions of the day. It is not known how the letters came to survive, but they were discovered by a certain Francis Blomefield when he was exploring the family home at Oxnead in 1735. He kept those he thought of historical value, and they ended up in the British Museum and the Bodleian Library at Oxford. A fifth volume was published by a William Frere in 1823, and the whole collection, entitled The Paston Letters and covering the years 1422 to 1509, was re-

G3b-