xxxxxA career as a prosperous Paris stockbroker made the

Frenchman Paul Gauguin a wealthy man, but in 1883, having tired of

the trappings of civilisation, he left his job and virtually

abandoned his wife and family to devote his days to painting. In

the 1870s he had come to know and work with the leading

Impressionists - notably Pissarro

and Cézanne - and this had convinced

him that his future lay as an artist. Anxious to experience the

raw intensity of life, he first joined the artists’ colony at

Pont-Aven in Brittany. There he immersed himself in the

ancient traditions and beliefs, using a simple design and areas of

strong unnatural colours to produce works such as The

Yellow Christ and Vision after the

Sermon. It was during this period, 1888, that he spent time in the South of France with the

Dutch painter Vincent Van Gogh, two months that ended with a threat upon Gauguin’s

life. It was soon after this that he paid his two visits to the

Island of Tahiti in the South Seas. It was there, fascinated by

the traditional culture and religious beliefs of the native

people, that he produced the works for which he became famous. His

style remained simple in design, but his colours became exotic. A

well known work of this time was the vast life-cycle entitled

Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we

going?. Others included Tahitian Girl

with a Flower, The Market, The Spirit of the Dead

Watching, The White Horse, Two Tahitian Women with Mango Blossoms, and Adam and Eve. His innovative design

influenced, in particular, Expressionism, a movement which used

distortion to evoke powerful inner emotions.

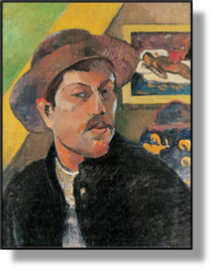

PAUL GAUGUIN 1848 -

1903 (Va, Vb,

Vc, E7)

Acknowledgements

Gauguin: Self-Portrait

– Musée d’Orsay; Breton Girls Dancing – National Gallery of Art,

Washington; The Yellow Christ – Albright-Knox Gallery,

Buffalo, NY; Vision of the Sermon – National Galleries of

Scotland, Edinburgh; Van Gogh painting – Rijksmuseum Vincent van

Gogh, Amsterdam; Where do we come from, where are we, where are we

going? – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; And the Gold of their Bodies

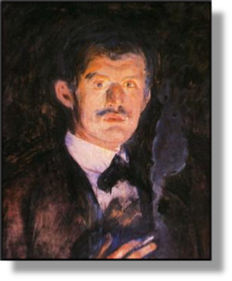

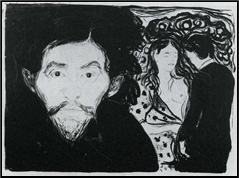

– Musée d’Orsay. Munch: Self-Portrait

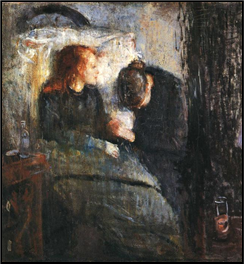

(detail) – National Museum, Oslo; The Sick Child – National

Museum, Oslo; The Scream – National Museum, Oslo; Anxiety – Munch

Museum, Oslo; Madonna – National Museum, Oslo; Moonlight –

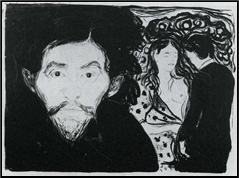

National Museum, Oslo; Jealousy (lithograph) – Tel Aviv Museum of

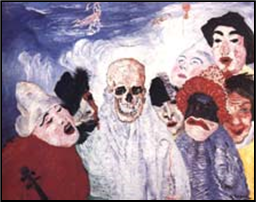

Art, Israel. Ensor: Death and the Masks

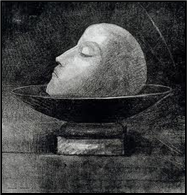

– Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Liège, Belgium. Redon: Head of a Martyr in a Bowl (charcoal) – Kroller-Muller

Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands. Bocklin:

Isle of the Dead – Old National Gallery, Berlin.

xxxxxLike his one-time friend Vincent Van Gogh, the

Frenchman Paul Gauguin was a post-impressionist painter who,

rejecting the Impressionist’s overriding aim to depict the

changing face of the natural world, used his bold, pure colours

and firm shapes to express his own deep-felt emotions,

aroused by ideas rather than appearance. As early as 1886,

therefore, he abandoned the “civilized” society of Paris - “a

desert for a poor man” as he put it - to experience the raw

intensity of life, first among the peasants of Brittany, and then,

ill and poverty stricken, among the natives of the South Pacific.

It was there, on the island of Tahiti, that he produced some of

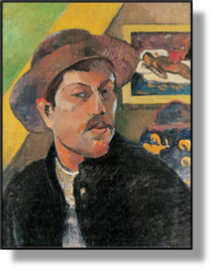

his best and well-known works. This self-portrait was

painted in 1893.

xxxxxLike his one-time friend Vincent Van Gogh, the

Frenchman Paul Gauguin was a post-impressionist painter who,

rejecting the Impressionist’s overriding aim to depict the

changing face of the natural world, used his bold, pure colours

and firm shapes to express his own deep-felt emotions,

aroused by ideas rather than appearance. As early as 1886,

therefore, he abandoned the “civilized” society of Paris - “a

desert for a poor man” as he put it - to experience the raw

intensity of life, first among the peasants of Brittany, and then,

ill and poverty stricken, among the natives of the South Pacific.

It was there, on the island of Tahiti, that he produced some of

his best and well-known works. This self-portrait was

painted in 1893.

xxxxxGauguin was

born in Paris, but soon after his birth the family went to live in

Lima, Peru, at the home of one of his mother’s relatives. His

father having died on the outward journey, in 1855 he returned to

France with his mother and older sister Mari, and they settled in

Orleans. At the age of 17, however, anxious to see more of the

world, he went to sea, serving on a merchant vessel for the next

five years. By the time he left the service in 1871, his mother

had died and a wealthy banker, Gustav Arosa, had became his

guardian. He found him a job with a Paris stockbroker and this

launched him on a successful business career. By 1883 he had money

in the bank, a good home, a competent wife named Mette, and five

children.

xxxxxBut by this

time Gauguin, tiring of city life, had found another and more

absorbing interest - painting. He had met the leading

Impressionists - including Pissarro and Cézanne - at his

guardian’s house during the 1870s, and from then on had joined

them for painting at weekends and holidays. He had also begun

exhibiting at their shows from 1879, and had met with some, albeit

limited success. With the coming of a stock market crash in 1883,

he decided to resign his post and begin painting for a living. He

wanted to get away from the pressures of civilisation and “be free

to paint every day”. But his income from his art work proved

totally inadequate. His savings quickly ran out and matters became

worse when the family moved to Copenhagen in his wife’s native

Denmark. He struggled to find work and eventually in 1885 he

returned to Paris, taking Clovis, his six-year old son, with

him. There he worked as a bill-poster to scrape a living, but

in the harsh winter that followed Clovis almost died of smallpox

and was returned to his mother. Gauguin stayed for a short while

at Pont-Aven, an artists’ colony in Brittany, and then, fully

abandoning his family, he set off to work as a navvy on the

building of the Panama Canal. This proved another failure. He was

struck down with fever and four months later, ill and penniless,

he returned to France and Brittany.

Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc

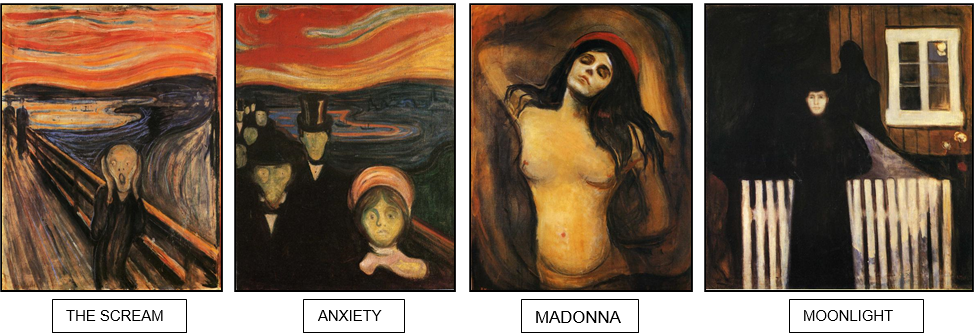

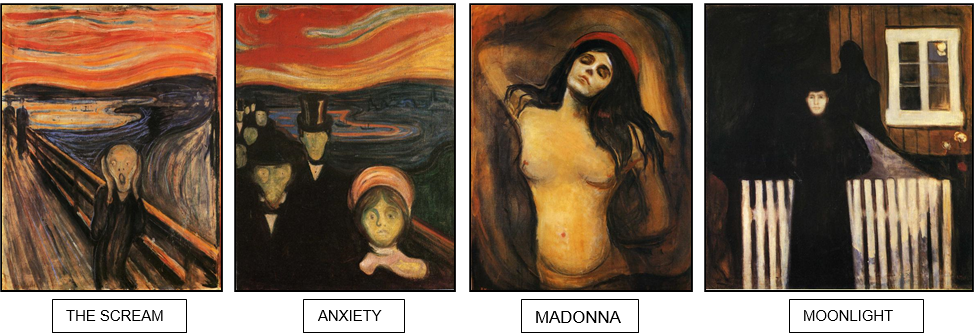

xxxxxThe Norwegian

painter Edvard Munch

(1863-1944) lost his mother and his favourite sister early on

in his life and this affected his personality. He was morbid and

introspective by nature, and this showed in his paintings. He did

produce landscapes and genre scenes during his career - many

in the style of the Impressionists - but during the last 20

years of the 19th century in particular, his works dwelt on

sickness, death, and the anxieties and fears of a troubled mind.

His paintings in this period included By the

Deathbed, Ashes, Death

in the Sickroom, The Death Bed,

and The Dead Mother. Especially

remembered today is his The Scream of

1893, a work depicting a ghost-like figure amid swirling,

violent colours - a cry of anguish “passing through Nature”.

These bleak, innermost feelings were also to be seen in such works

as Anxiety, Madonna,

and Moonlight, contained, with many

others, in his so-called Frieze of Life.

Early on, his paintings met with derision, but later in his career

his innovative style gained recognition, and he came to be

regarded as a man of vision. The display of emotional content in

his paintings was influenced by the works of the French artists

Paul Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh, and his distorted figures and

clash of bold colours paved the way for Expressionism, a movement

of the early 20th century.

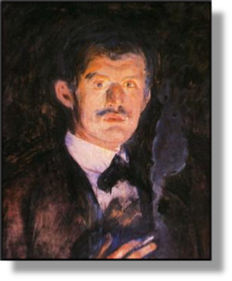

xxxxxThe Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863-1944)

was much influenced early in his career by the works of the French

Post-Impressionist Paul Gauguin and his fellow countryman

Vincent Van Gogh. His major paintings, belonging to the period

1892 to 1908, are characterized by their use of flat areas of

strong colour and their powerful emotional content, but many

contain, too, the exaggerated, distorted face and figures that

make him a forerunner of Expressionism. He is particularly

remembered today for his The Scream of

1893, the product of a mind in torment, and his Frieze

of Life, a series of paintings containing very personal

and, at times, disturbing images of life, love and death. (Self-portrait illustrated here.)

xxxxxThe Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863-1944)

was much influenced early in his career by the works of the French

Post-Impressionist Paul Gauguin and his fellow countryman

Vincent Van Gogh. His major paintings, belonging to the period

1892 to 1908, are characterized by their use of flat areas of

strong colour and their powerful emotional content, but many

contain, too, the exaggerated, distorted face and figures that

make him a forerunner of Expressionism. He is particularly

remembered today for his The Scream of

1893, the product of a mind in torment, and his Frieze

of Life, a series of paintings containing very personal

and, at times, disturbing images of life, love and death. (Self-portrait illustrated here.)

xxxxxMunch was

born in Loten in southern Norway, the second son of five children.

His father was a doctor working with the army. The family moved to

Oslo (then called Christiania) a year after his birth, and it was

there that tragedy struck. His mother died of tuberculosis when he

was five, followed by the death of his favourite sister Sophie -

also from tuberculosis - in 1877. These loses had a profound

effect upon his character. Sickly by nature and spending long

hours confined in the family apartment, he became morbid and

introverted. Of this period he later wrote, “Illness, madness and

death were the black angels that kept watch over my cradle and

accompanied me all my life”.

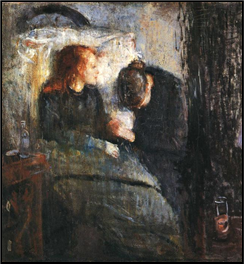

xxxxxIn 1881 he attended the State School of Art and

Crafts in Oslo, and the following year he became a member of a

small group of artists and writers, the Bohemians, bent on sexual

and artistic freedom. At this time, however, due to his retiring

nature, Munch tended to confine his work to the portrayal of

family and friends, such as Aunt Karen in the

Rocking Chair and At the Coffee Table, both of 1883, and

Family Evening, produced the following

year. In 1884, however, he won a three-week scholarship to

study in Paris and this brought him into direct contact with the

Impressionists. The influence of their works can be detected in

his first masterpiece, The Sick Child

of 1886 (here illustrated), a moving, sensitively-painted scene recalling

the death of his sister.

xxxxxIn 1881 he attended the State School of Art and

Crafts in Oslo, and the following year he became a member of a

small group of artists and writers, the Bohemians, bent on sexual

and artistic freedom. At this time, however, due to his retiring

nature, Munch tended to confine his work to the portrayal of

family and friends, such as Aunt Karen in the

Rocking Chair and At the Coffee Table, both of 1883, and

Family Evening, produced the following

year. In 1884, however, he won a three-week scholarship to

study in Paris and this brought him into direct contact with the

Impressionists. The influence of their works can be detected in

his first masterpiece, The Sick Child

of 1886 (here illustrated), a moving, sensitively-painted scene recalling

the death of his sister.

xxxxxThree years

later, following the success of his first one-man show, he

gained a state scholarship and returned to Paris, this time for

three years. It was during this stay that he came to admire in

particular the works of the post impressionists, notably Paul

Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh, and their emotional impact had a

marked effect upon his style and subject matter. In 1891 he did

produce, amongst others, Rue Lafayette

and Promenade des Anglais, Nice,

scenes that clearly owed something to Impressionism (and

Pointillism at times), but for the most part he now discarded

reality for the creation of strong emotions centred around the

universal themes of sickness, love, anxiety, despair and death. It

was these bleak, innermost feelings that filled his own troubled

mind and needed to be expressed. His art, he explained at the

time, was “an attempt to explain to myself my relationship with

life”. In order to understand himself, there was a need to “paint

living people who breathe, feel, suffer and love” Not the

impression of reality, but the expression of his soul was what he

wanted to commit to canvas.

xxxxxAs a

consequence, over the next ten years or so - his symbolist

phase - he produced a volume of poignant but depressing works

that plumbed the depths of man’s darkest feelings: three on

melancholy, three on jealousy, and numerous scenes portraying his

obsession with sickness and death. These included By

the Deathbed, Ashes, Death

in the Sickroom, The Death Bed,

and The Dead Mother.

xxxxxAnd his

uneasy relationship with women and sex in general is obliquely

revealed in his highly charged image of Madonna,

his Puberty - the awakening of

sexual feelings -, his Three Stages of

Woman, its sequel, the enigmatic The

Dance of Life, and Man and Woman.

And to this period belongs his famous The

Scream, an anguished expression of solitude and abject

fear, created by a ghost-like, alien figure, the frantic

swirling of powerful colours, and a blood-red sky. It was a

cry, as he put it, that was “passing through Nature”.

xxxxxOther works

belonging to this period were Tahitian Girl

with a Flower, The Market, The Spirit of the Dead

Watching, The White Horse, Two Tahitian Women with Mango Blossoms, Horsemen on the Beach,

and Adam and Eve.

xxxxxGauguin

never found the tropical paradise he was after, though it did

become his spiritual home. Indeed, for much of his time in the

South Seas he was desperately unhappy, lacking money and suffering

from syphilis. At one time, in 1897, he attempted suicide by

taking arsenic, and his last years were marred by his support of

the native people in their dispute with the colonial

administration and the Catholic Church. In 1903 the authorities

sentenced him to three months’ imprisonment for what they termed

“defamation”, but he died before the result of his appeal and was

buried in Calvary Cemetery, Atuona.

xxxxxLike the

other post-impressionist painters - notably Vincent Van

Gogh and Paul Cézanne - the works of Gauguin greatly

influenced many of the trends of 20th century art. In particular,

his creation of strong emotions, “found in the depth of one’s

being”, played an important part in the development of

Expressionism, a movement noted for its use of exaggeration and

distortion to evoke powerful inner emotions. As we shall see,

among the pioneers of this movement was the Norwegian painter

Edvard Munch.

xxxxxIncidentally, when living as a prosperous stockbroker in Paris

during the 1870s and early 1880s, Gauguin spent some 17,000 francs

on buying paintings by Claude

Monet, Camille Pissarro, Auguste Renoir and other Impressionists.

……

xxxxx…… A vivid account of his life is to be found in his

journals, letters, and his autobiographical work Noa

Noa (meaning Fragrance, Fragrance),

a recording of his experiences and emotions during his first stay

in Tahiti, published in 1897. ……

xxxxx…… Inx1916 the English writer

and playwright Somerset Maugham (1874-1965) travelled to the South Seas to

obtain material for his novel The Moon and

Sixpence, a story based on the life of Paul Gauguin.

xxxxxNot

surprisingly these works caused something of a stir, both within

the artistic world and the general public. An exhibition in Berlin

in 1892, organised by the city’s Union of Artists, attracted

widespread condemnation. Within a week he was ordered to remove

his “daubs”, but this “Berlin Scandal”, as it came to be known,

brought him notoriety, and, in the long term, popularity. To take

advantage of his sudden fame, he embarked upon an extensive tour

of the major cities of Germany and Scandinavia in order to display

his “degenerate works”. As a result Munch became a household

named. For the most part his works received little approval at

this stage, but quite a large number saw purpose and merit in his

unique approach - including his fellow countryman and friend

the novelist Henrik Ibsen - and this number was destined to

grow.

xxxxxFrom the

time of this all-important exhibition to the year 1908, Munch

lived mainly in Germany. It was there in the 1890s that he

compiled his Frieze of Life, a

“symphonic arrangement” of many of his greatest paintings -

symbolic, gloomy images in which faces and figures were often

distorted, and his brushwork, thick and contorted, produced shock

waves of intense colour. These were the hallmarks of his own,

innovative style, the means by which he portrayed the darker

themes of life - misery, anxiety, fear, sickness, loneliness

and death.

xxxxxThe turn of the century did see something of a move

away from these introspective works - with paintings like Forest, Ladies on the

Bridge and Winter Landscape,

Elgersburg, but in 1908, his emotional instability and

persecution complex, together with his heavy drinking and a

turbulent love affair, brought about a chronic nervous breakdown,

and he spent eight months in a sanatorium in Copenhagen. By then,

however, the innovative value of his work was beginning to be

recognised. In 1908 he was made a Knight of the Order of St. Olav

for his contribution to art, and enthusiasm for his paintings was

beginning to grow. In addition he was becoming highly respected

for his work as a graphic artist. In his making of etchings,

lithographs and colour woodcuts, a skill learnt in Paris in 1896,

he showed a remarkable talent, and he reproduced a number of his

major works in this new medium. Shown here is his lithograph Jealousy.

xxxxxThe turn of the century did see something of a move

away from these introspective works - with paintings like Forest, Ladies on the

Bridge and Winter Landscape,

Elgersburg, but in 1908, his emotional instability and

persecution complex, together with his heavy drinking and a

turbulent love affair, brought about a chronic nervous breakdown,

and he spent eight months in a sanatorium in Copenhagen. By then,

however, the innovative value of his work was beginning to be

recognised. In 1908 he was made a Knight of the Order of St. Olav

for his contribution to art, and enthusiasm for his paintings was

beginning to grow. In addition he was becoming highly respected

for his work as a graphic artist. In his making of etchings,

lithographs and colour woodcuts, a skill learnt in Paris in 1896,

he showed a remarkable talent, and he reproduced a number of his

major works in this new medium. Shown here is his lithograph Jealousy.

xxxxxMunch

returned to Norway in 1910 and worked there in virtual seclusion

until his death in January 1944. In the 1920s, however, large

exhibitions of his works were held in cities across Europe. By a

conscious effort, his later works were less pessimistic and, as a

result, more colourful. He produced landscapes and studies of

people working on the land, as well as a number of self portraits.

To these later years belong Workers on their

way Home, Lumberjack, Spring

Ploughing, The Haymaker, Horse Team and a number of self-portraits.

And, in addition, he produced nine murals for the Festival Hall of

Oslo University, each 15ft in height and depicting universal

force. He spent his last years at his estate at Ekely, not far

from Oslo, and it was there that he died. He left 1000 paintings

and close on 20,000 prints to the city of Oslo, and these are now

housed in the Munch Museum, purposefully built in 1963. An

isolated, troubled figure, Munch stands today as Norway’s greatest

painter and graphic artist. A man of vision at the opening of the

20th century, his haunting, distorted images captured the essence

of symbolism, and paved the way for Expressionism, a movement

marked by contorted figures, a clash of bold colours, and violent

emotion.

xxxxxIncidentally, among his

friends were several writers, including his fellow countryman and

playwright Henrik Ibsen, and the Swedish novelist August

Strindberg. He designed sets for a number of Ibsen’s plays, and

often discussed the writings of the German philosopher Friedrich

Nietzsche with Strindberg. He produced portraits of both men. ……

xxxxx…… In February 1994 four men broke into the National

Gallery in Oslo and stole its version of The

Scream, but it was recovered undamaged three months

later. Then ten years later, in August 2004, masked gunmen entered

the Munch Museum in Oslo in broad daylight and stole its version

of The Scream and Madonna

(together worth an estimated $100 million). Both works, were

recovered - slightly damaged - in August 2006.

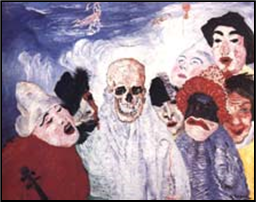

xxxxxThreexother artists

of this time are worthy of mention. The Belgian painter and

printmaker James Ensor

(1860-1949) also anticipated Expressionism. A member of Les Vingts (The Twenty),

- a group bent on developing new forms of art - his

macabre works of the 1880s and 1890s, such as Entry

of Christ into Brussels, Intrigue, and Death and the Masks (illustrated), were full of tormented figures, animated skeletons,

and grotesque phantoms and corpses. At first, as in the case of

Munch, his paintings met with derision, but in later years his

surreal works gained in popularity. Also noted for his drawings and

etchings, he spent almost his entire life in Ostend.

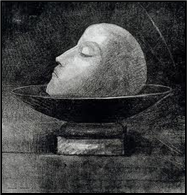

xxxxxAndxanother artist

remembered for his macabre, surreal subjects was the Frenchman Odilon Redon (1840-1916).

Produced in prints and charcoal drawings and full of strange,

frightening images, his gloomy, black and white works included The Comedy of Death, The

Crying Spider, Death: my irony

surpasses all others, and Head of a

Martyr in a Bowl (illustrated). Suchxworks

linked him with the Decadent Movement in which the artist had no limits to his or her

means of expression. However, in 1890, having met with the

Impressionists and become particularly friendly with both Paul

Gauguin and Georges Seurat, he broke with the past and began a new

career as a colourist. Working in pastels and oils, he opened the

door to life and light, producing flowers, portraits and bizarre

fantasies in bright, warm colours.

xxxxxAndxanother artist

remembered for his macabre, surreal subjects was the Frenchman Odilon Redon (1840-1916).

Produced in prints and charcoal drawings and full of strange,

frightening images, his gloomy, black and white works included The Comedy of Death, The

Crying Spider, Death: my irony

surpasses all others, and Head of a

Martyr in a Bowl (illustrated). Suchxworks

linked him with the Decadent Movement in which the artist had no limits to his or her

means of expression. However, in 1890, having met with the

Impressionists and become particularly friendly with both Paul

Gauguin and Georges Seurat, he broke with the past and began a new

career as a colourist. Working in pastels and oils, he opened the

door to life and light, producing flowers, portraits and bizarre

fantasies in bright, warm colours.

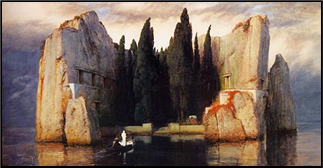

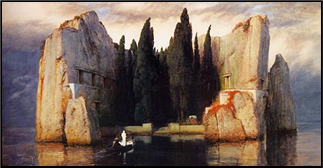

xxxxxArnoldxxBocklin (1827-1901) was

a Swiss symbolist painter. A romantic by nature, his paintings

created a weird, fantasy world where death - as in the works

of Munch - played a prominent part. He is best known today

for the five versions of his Isle of the Dead

(one illustrated here), produced between 1880 and 1886. Evoked in part by

the English Cemetery near his studio in Florence, this mysterious,

haunting painting - seen by some as a soul’s passage to the

afterlife - was to be the inspiration for a number of works,

including a symphonic poem by the Russian composer Sergei

Rachmaninoff, and a painting by the Spanish artist Salvador Dali.

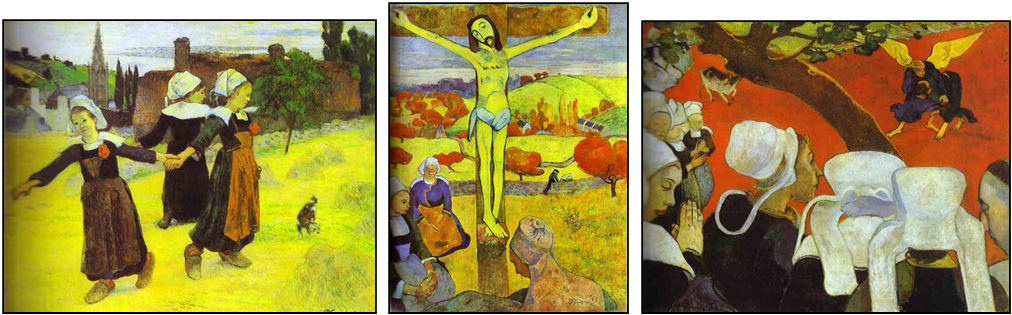

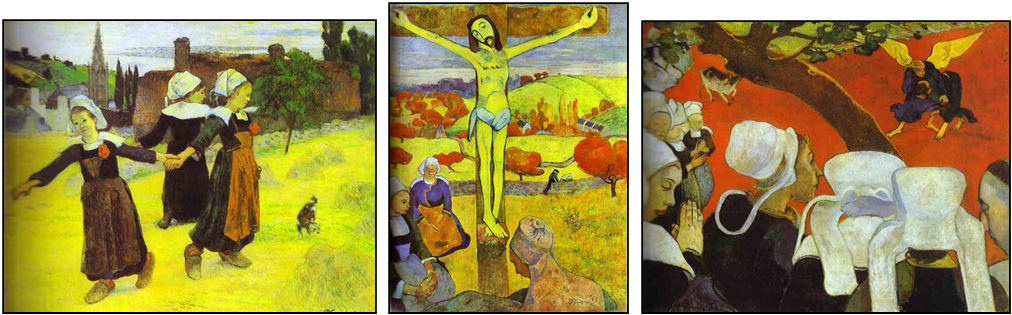

xxxxxFour the

next five years he spent most of his time at Pont-Aven.

There, at the age of 40, he began to develop his own, innovative

style. Using strong, evocative colours and firmly defined flat,

bold planes, he captured on canvas not only the beauty of the

rugged countryside, but also the ancient traditions and beliefs of

the local peasants, a people as hardy as the region they

inhabited. To this period belongs (left to right) his Breton

Girls Dancing, The

Yellow Christ, an image remarkable for its vibrant,

unnatural colours and dramatic simplicity, and Vision

after the Sermon, a powerful symbolic and emotional work.

He called these decorative, almost abstract qualities “synthetic

symbolism”, the merging of a flat, simplified design with

powerful, exaggerated colours.

xxxxxIn October 1888, after

some hesitation, Gauguin accepted an invitation to join Vincent

Van Gogh in the South of France. He had met and worked with the

Dutch painter in 1886, and at that time had not particularly liked

him as a person nor rated him highly as a painter. However, winter

was about to begin in Brittany, and the promise of the clear skies

and warm sunshine of Province overcame his misgivings. As we have

seen, the visit, seen by Van Gogh as the beginning of an artists’

colony in the South, proved a total failure. Gauguin’s arrogance

and Van Gogh’s obstinacy made up a recipe for disaster. They were

soon quarrelling over art and life in general, heated arguments

which were fuelled by excessive drinking and rival demands for the

local prostitutes. Matters came to a head at the end of December

when Van Gogh threatened Gauguin with a razor. Gauguin hurried

back to Paris, and Van Gogh then turned the blade upon himself,

severing part of his left ear. Illustrated here is Gauguin’s

painting of Van Gogh at work on his famous Vase

of Sunflowers of 1888.

xxxxxIn October 1888, after

some hesitation, Gauguin accepted an invitation to join Vincent

Van Gogh in the South of France. He had met and worked with the

Dutch painter in 1886, and at that time had not particularly liked

him as a person nor rated him highly as a painter. However, winter

was about to begin in Brittany, and the promise of the clear skies

and warm sunshine of Province overcame his misgivings. As we have

seen, the visit, seen by Van Gogh as the beginning of an artists’

colony in the South, proved a total failure. Gauguin’s arrogance

and Van Gogh’s obstinacy made up a recipe for disaster. They were

soon quarrelling over art and life in general, heated arguments

which were fuelled by excessive drinking and rival demands for the

local prostitutes. Matters came to a head at the end of December

when Van Gogh threatened Gauguin with a razor. Gauguin hurried

back to Paris, and Van Gogh then turned the blade upon himself,

severing part of his left ear. Illustrated here is Gauguin’s

painting of Van Gogh at work on his famous Vase

of Sunflowers of 1888.

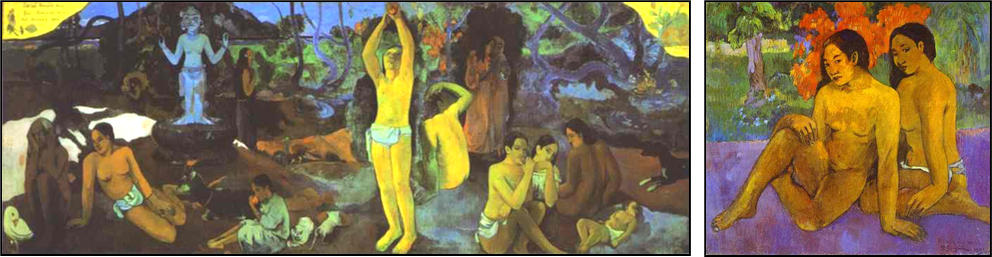

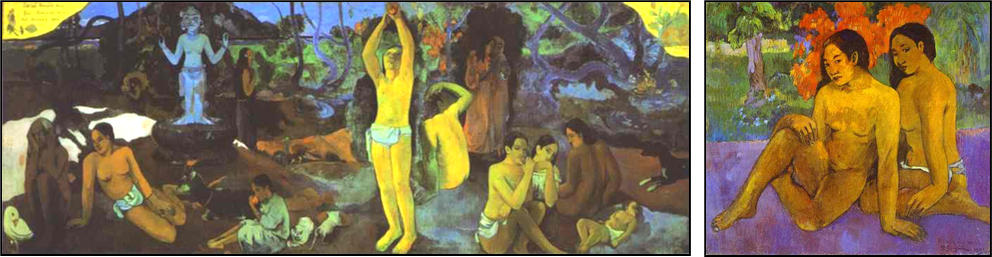

xxxxxGauguin

spent the next two and a half years working in Paris and Brittany.

He produced some promising works during this period, but he was

still short of money and he remained unsettled in mind. He

disliked “everything that is artificial and conventional”, and

yearned for the joy of a primitive life. In the Spring of 1891 he

found it in the rural area of Mataiea on the South Sea island of

Tahiti, but his paradise was short lived. His meagre savings began

to run out and this, together with ill-health, forced him to

return home. In Paris, however, he made some money from the

canvases he brought back, and this, plus a small legacy from an

uncle in Orleans, gave him sufficient funds to return to the

Tropics. He arrived back in Tahiti the summer of 1895 and over the

next eight years - the last two spent at Atuona in the

Marquesas Islands - he produced the works for which he is

most famous. Here he took a special interest in the traditional

culture and spiritual beliefs of these gentle Polynesian people.

The simplicity of design remained, but his colours became highly

exotic. One of his best known works, the life-cycle entitled

Where do we come from? What are we? Where are

we going?, has life beginning with the baby on the right

and ending with the wizened old woman on the left (illustrated below). This huge

canvas poses the questions but makes no attempt at giving the

answers. Also illustrated below is And the Gold

of Their Bodies, one of his many nude studies.

xxxxxLike his one-

xxxxxLike his one- xxxxxThe Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863-

xxxxxThe Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863- xxxxxIn 1881 he attended the State School of Art and

Crafts in Oslo, and the following year he became a member of a

small group of artists and writers, the Bohemians, bent on sexual

and artistic freedom. At this time, however, due to his retiring

nature, Munch tended to confine his work to the portrayal of

family and friends, such as Aunt Karen in the

Rocking Chair and At the Coffee Table, both of 1883, and

Family Evening, produced the following

year. In 1884, however, he won a three-

xxxxxIn 1881 he attended the State School of Art and

Crafts in Oslo, and the following year he became a member of a

small group of artists and writers, the Bohemians, bent on sexual

and artistic freedom. At this time, however, due to his retiring

nature, Munch tended to confine his work to the portrayal of

family and friends, such as Aunt Karen in the

Rocking Chair and At the Coffee Table, both of 1883, and

Family Evening, produced the following

year. In 1884, however, he won a three-

xxxxxThe turn of the century did see something of a move

away from these introspective works -

xxxxxThe turn of the century did see something of a move

away from these introspective works -

xxxxxAndxanother artist

remembered for his macabre, surreal subjects was the Frenchman Odilon Redon (1840-

xxxxxAndxanother artist

remembered for his macabre, surreal subjects was the Frenchman Odilon Redon (1840-

xxxxxIn October 1888, after

some hesitation, Gauguin accepted an invitation to join Vincent

Van Gogh in the South of France. He had met and worked with the

Dutch painter in 1886, and at that time had not particularly liked

him as a person nor rated him highly as a painter. However, winter

was about to begin in Brittany, and the promise of the clear skies

and warm sunshine of Province overcame his misgivings. As we have

seen, the visit, seen by Van Gogh as the beginning of an artists’

colony in the South, proved a total failure. Gauguin’s arrogance

and Van Gogh’s obstinacy made up a recipe for disaster. They were

soon quarrelling over art and life in general, heated arguments

which were fuelled by excessive drinking and rival demands for the

local prostitutes. Matters came to a head at the end of December

when Van Gogh threatened Gauguin with a razor. Gauguin hurried

back to Paris, and Van Gogh then turned the blade upon himself,

severing part of his left ear. Illustrated here is Gauguin’s

painting of Van Gogh at work on his famous Vase

of Sunflowers of 1888.

xxxxxIn October 1888, after

some hesitation, Gauguin accepted an invitation to join Vincent

Van Gogh in the South of France. He had met and worked with the

Dutch painter in 1886, and at that time had not particularly liked

him as a person nor rated him highly as a painter. However, winter

was about to begin in Brittany, and the promise of the clear skies

and warm sunshine of Province overcame his misgivings. As we have

seen, the visit, seen by Van Gogh as the beginning of an artists’

colony in the South, proved a total failure. Gauguin’s arrogance

and Van Gogh’s obstinacy made up a recipe for disaster. They were

soon quarrelling over art and life in general, heated arguments

which were fuelled by excessive drinking and rival demands for the

local prostitutes. Matters came to a head at the end of December

when Van Gogh threatened Gauguin with a razor. Gauguin hurried

back to Paris, and Van Gogh then turned the blade upon himself,

severing part of his left ear. Illustrated here is Gauguin’s

painting of Van Gogh at work on his famous Vase

of Sunflowers of 1888.