ELIZABETH FRY 1780 -

xxxxxThe English philanthropist Elizabeth Fry, a leading Quaker, devoted much of her time to the care of the poor. In 1813, after a visit to Newgate prison in London, she became particularly interested in penal reform, especially in the treatment of women prisoners. Like her compatriot John Howard before her, she campaigned for improvements, calling for the classification of prisoners, separation of the sexes, and better food and clothing. She also argued that prisoners needed to be usefully employed and educated, including religious instruction. She spent many years visiting prisons in Britain and on the continent, and became famous for her reading and preaching at Newgate. She also voiced her concern about the appalling conditions aboard ships taking convicts to Australia, and demanded better hospital care for the mentally disturbed.

xxxxxThe English philanthropist Elizabeth Fry, née Gurney, was born at Norwich, Norfolk, the daughter of a wealthy banker. She became a Quaker, like her father, in 1798, and two years later married Joseph Fry, a London merchant. Despite a large family, she devoted much of her time to the care of the poor, and for this work was made a “minister” by the Society of Friends in 1811. She became particularly interested in penal reform after visiting Newgate prison in London in 1813. From this time onwards she began visiting prisons all over the country, travelling to Scotland and Ireland and, later, making lengthy tours on the continent. Apart from reading the bible and preaching to the inmates, she wrote reports on the conditions she found, and testified before parliamentary committees.

xxxxxThe English philanthropist Elizabeth Fry, née Gurney, was born at Norwich, Norfolk, the daughter of a wealthy banker. She became a Quaker, like her father, in 1798, and two years later married Joseph Fry, a London merchant. Despite a large family, she devoted much of her time to the care of the poor, and for this work was made a “minister” by the Society of Friends in 1811. She became particularly interested in penal reform after visiting Newgate prison in London in 1813. From this time onwards she began visiting prisons all over the country, travelling to Scotland and Ireland and, later, making lengthy tours on the continent. Apart from reading the bible and preaching to the inmates, she wrote reports on the conditions she found, and testified before parliamentary committees.

xxxxxPrison reform was certainly a pressing social need. Conditions in the country’s prisons at this time were atrocious. Be they thieves, murderers, debtors, or just waiting to be tried, men, women and children were herded together like animals, living their days in filthy conditions, prone to disease, and at the mercy of each other. The food allowance was meagre. Only those who had ready cash were able to pay the jailer or “turnkey” to keep them fed, and prisoners who had no family or friends to care for them had to beg for scraps or come close to starvation. As we have seen, in 1777 the London philanthropist John Howard published a book on the state of prisons in England and Wales. He advocated basic rules of hygiene and the setting up of rehabilitation centres, but little was done by way of improvement.

xxxxxIn her own charity work, Fry was particularly appalled at the treatment of female prisoners and, after her visit to Newgate (illustrated) made public her concern, calling for a separation of the sexes, the classification of prisoners, better food and clothing, and a greater degree of supervision. She also argued that prisoners needed to be usefully employed, and given religious and secular instruction. In 1817 she set up the Association for the Improvement of Female Prisoners to provide for some of these needs and, together with her brother, Joseph Gurney, issued a report on prison reform two years later.

xxxxxElizabeth Fry was one of the leading prison reformers of her day. Apart from her work in Britain, she visited prisons in Europe where she lectured to a wide audience and urged governments to institute prison reform. At home she complained of the conditions endured by convicts on their voyage to penal settlements in Australia, and she also put forward ideas to improve hospital treatment -

xxxxxIncidentally, her work for the poor and her tireless efforts in the cause of prison reform made her famous. She was referred to as “the genius of good” and “the Prisoners’ Friend”, and her reading sessions to the prisoners in Newgate became one of the “sights” of London. ……

xxxxx…… She died at Ramsgate, Kent, in 1845, and was buried at the Friends’ Burial Grounds at Barking, Essex. £4,000 was raised in her memory and, fittingly, this was used to establish the Elizabeth Fry Refuge in Mare Street, Hackney, London, a hostel for women in need. In 2002 her portrait was featured on the Bank of England £5 note, and this renewed interest in her. The following year a new memorial stone was erected in her memory, a marble plaque bearing her portrait and brief details of her life. ……

xxxxx…… She died at Ramsgate, Kent, in 1845, and was buried at the Friends’ Burial Grounds at Barking, Essex. £4,000 was raised in her memory and, fittingly, this was used to establish the Elizabeth Fry Refuge in Mare Street, Hackney, London, a hostel for women in need. In 2002 her portrait was featured on the Bank of England £5 note, and this renewed interest in her. The following year a new memorial stone was erected in her memory, a marble plaque bearing her portrait and brief details of her life. ……

xxxxx…… In 1806 work began on the building of Princetown Prison, situated on the bleak area of Dartmoor in Devon. It was originally built to hold French prisoners from the Napoleonic Wars, but since 1850 has been one of England’s major centres for serious offenders.

Acknowledgements

Fry: detail, after the English genre painter Charles Robert Leslie (1794-

Including:

Robert Owen

G3c-

xxxxxAnother social reformer at this time was the Welsh cotton mill owner Robert Owen (1771-

xxxxxIt was in 1813 that another social reformer at this time, the self-

xxxxxIt was in 1813 that another social reformer at this time, the self-

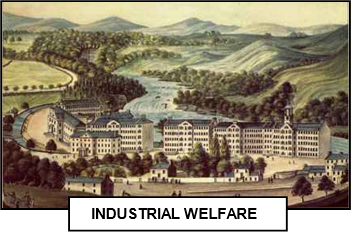

xxxxxOwen was born in Newtown, Wales, youngest son of the village postmaster. He began his working life as an apprentice draper, and by the age of 20 had saved and borrowed sufficient funds to become the manager of a large textile mill in Manchester. In 1800 he persuaded his partners to purchase the New Lanark Mills in Lanarkshire, Scotland, and it was then that, appalled by the squalid state then prevailing in the factory system, he began his social experiments. Initially, these prove d costly, and in 1813 he was obliged to buy out his disgruntled partners and set up a new undertaking financed by philanthropists and reformers, among whom was the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham. It was then that he was able to carry out a full programme of reform. He quickly set about improving the housing and working conditions of his employees, introducing medical care for their families and providing education for the young -

d costly, and in 1813 he was obliged to buy out his disgruntled partners and set up a new undertaking financed by philanthropists and reformers, among whom was the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham. It was then that he was able to carry out a full programme of reform. He quickly set about improving the housing and working conditions of his employees, introducing medical care for their families and providing education for the young -

xxxxxThis welfare scheme included Britain’s first infant school, opened in 1816, an “Institute for the Formation of Character”, and leisure activities for his employees and their families. Contrary to expectations, these measures proved highly successful financially as well as socially. They increased commercial output and produced a substantial profit as a result. Many industrialists, politicians and social reformers visited the mills to learn lessons from the enterprise.

xxxxxIn 1817, anxious to expand upon this idea of a model industrial community living in harmony, he proposed the setting up of “villages of unity and co-

xxxxxIn 1817, anxious to expand upon this idea of a model industrial community living in harmony, he proposed the setting up of “villages of unity and co-

xxxxxIn the early 1830s Owen became a leading figure in the emerging trade union movement, but his attempts to combine the country’s work force in his Grand National Consolidated Trades Union proved premature and met with failure. However, the Rochdale Pioneers, an international co-

xxxxxOwen’s influence on the continent was substantial. The touch of communism in his doctrines -

xxxxxIn his later years, Owen spent a great deal of his time putting forward his ideas on the place of education, religion and marriage in society, and supporting birth control for the poor. He gave a full and lucid account of his theories in his Book of the New Moral World, produced in seven parts and completed in 1844. Apart from his marked influence on the growth of socialism in Britain -

xxxxxIn his later years, Owen spent a great deal of his time putting forward his ideas on the place of education, religion and marriage in society, and supporting birth control for the poor. He gave a full and lucid account of his theories in his Book of the New Moral World, produced in seven parts and completed in 1844. Apart from his marked influence on the growth of socialism in Britain - efforts.

efforts.

xxxxxIncidentally, the community known as New Harmony, established by Owen in Indiana, replaced a commune set up by the German-

xxxxx…… The Grand National Consolidated Trades Union, founded by Owen in 1833, proved impractical at the time and was disbanded the following year, but it had an important consequence. As we shall see, the six Dorset farm labourers -