xxxxxThe Franco-

THE FRANCO-

Acknowledgements

Leopold: date and artist unknown. Telegram: a facsimile from the Political Archives of the German Foreign Office, Berlin. Sedan: colour lithograph, date and artist unknown – Musée de la Ville de Paris, Musée Carnavalet, Paris. Meeting: by the German painter Wilhelm Camphausen (1818-

xxxxxThe Franco-

xxxxxOstensibly, as we have seen, the cause of the conflict had its roots in the Third Carlist War in Spain. With the deposition of Isabella II in 1868 there was need for a constitutional monarch, and Bismarck, seizing the opportunity, gave his full support to a German candidate, Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern-

xxxxxOstensibly, as we have seen, the cause of the conflict had its roots in the Third Carlist War in Spain. With the deposition of Isabella II in 1868 there was need for a constitutional monarch, and Bismarck, seizing the opportunity, gave his full support to a German candidate, Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern-

xxxxxIn view of the strength of opposition aroused in France, a few days later Leopold did in fact withdraw his acceptance, but then Napoleon, goaded by his government, went one step further. At an informal meeting on the 13th July, held at the Spa resort of Ems between the French ambassador in Prussia, Vincent Benedetti, and the Prussian Kaiser, Wilhelm I, he demanded a guarantee that no member of the Hohenzollern family would ever be a candidate for the Spanish throne. The Kaiser, firmly but politely, refused to give such an undertaking, and gave notice that he had nothing further to say to the ambassador and was not prepared to receive him again -

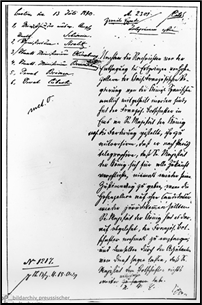

xxxxxA report of this meeting, the famous “Ems Telegraph” (or Despatch), was sent to Bismarck that evening, and this gave him the opportunity he was looking for. Before releasing an account of this informal discussion to the Press and foreign embassies, he slightly but craftily modified the wording so as to imply that both the ambassador and the Kaiser had insulted each other and that, as a consequence, diplomatic relations had been broken off. It was, as he later put it, “a red rag to the Gallic bull”. (“Doctored” account here illustrated). Napoleon, whose government had spoken earlier of being willing to take the appropriate action “without weakness or hesitation”, felt duly insulted, and France declared war on Prussia on the 19th July, 1870. Napoleon doubtless saw the war as a necessary opportunity to cut Prussia down to size but, in reality, quite the opposite transpired.

xxxxxA report of this meeting, the famous “Ems Telegraph” (or Despatch), was sent to Bismarck that evening, and this gave him the opportunity he was looking for. Before releasing an account of this informal discussion to the Press and foreign embassies, he slightly but craftily modified the wording so as to imply that both the ambassador and the Kaiser had insulted each other and that, as a consequence, diplomatic relations had been broken off. It was, as he later put it, “a red rag to the Gallic bull”. (“Doctored” account here illustrated). Napoleon, whose government had spoken earlier of being willing to take the appropriate action “without weakness or hesitation”, felt duly insulted, and France declared war on Prussia on the 19th July, 1870. Napoleon doubtless saw the war as a necessary opportunity to cut Prussia down to size but, in reality, quite the opposite transpired.

xxxxxThis declaration of war gave effect to Bismarck’s two major objectives. Firstly, the independent states of southern Germany, having no desire to support the French, threw in their lot with the North German Confederation, thereby anticipating the unification of Germany. Secondly, convinced that Prussia, assisted by the German states, was fully capable of overthrowing the French Empire (powerful though it was thought to be), he saw the war as means of establishing Germany, led by Prussia, as the dominant power in Europe. His confidence in the military strength of Prussia was not misplaced.

xxxxxUnderxthe direction of General Helmuth von Moltke (1800-

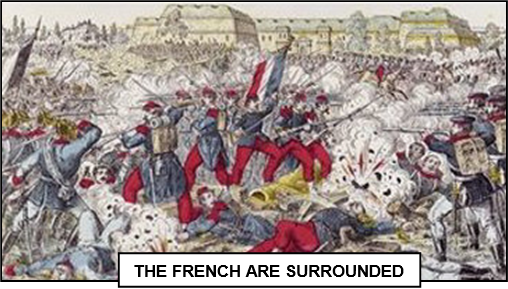

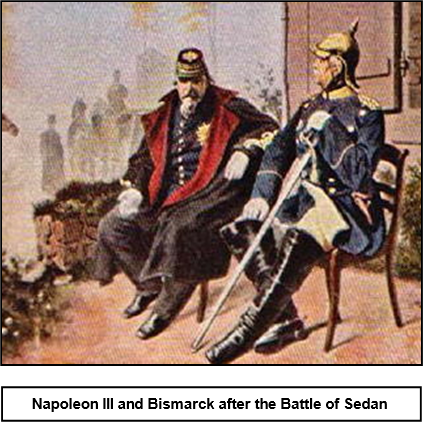

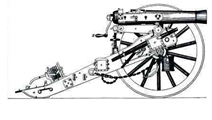

xxxxxThe Battle of Sedan, in which the French army was commanded by Napoleon III himself, proved the decisive engagement. The Prussians, having encircled the town with troops and artillery, attacked the French positions on the first day of September. The concentrated bombardment of their Krupp six pounders -

xxxxxThe Battle of Sedan, in which the French army was commanded by Napoleon III himself, proved the decisive engagement. The Prussians, having encircled the town with troops and artillery, attacked the French positions on the first day of September. The concentrated bombardment of their Krupp six pounders -

xxxxxAs noted earlier, on his release Napoleon III spent his last years with his wife and young son at Chislehurst in Kent, England, ever haunted by his military failure and the collapse of the country he had endeavoured to serve so well. He died in January 1873, and his final resting place was at the imperial crypt at St. Michael’s Abbey in Farnborough, Hampshire. In his early years as Emperor he did much to enhance the status of France both at home and internationally, but in the end he did bring about the total collapse of the nation in his charge, and that fact was never likely to be forgotten or forgiven.

xxxxxBut the outcome of the Battle of Sedan did not bring about an immediate cessation of hostilities. When news of the disaster reached Paris, republicans proclaimed the Third Republic, and a Government of National Defence was hurriedly established to defend the capital and continue the fight in the provinces. As we shall see, however, Paris was besieged and forced to surrender early in 1871 after a prolonged artillery bombardment, and French forces in the provinces, hastily assembled, proved no match for the Prussian army. Finally, in May a Commune, a revolutionary government set up in Paris in defiance of the peace settlement, was brought to a bloody end. All that remained was for the German Empire -

xxxxxIncidentally, in the war at sea the French fared no better. Their navy did attempt to blockade the North German coast, but, due to poor organisation, it did not prove very effective. Furthermore, a planned invasion of this coast line, to draw Prussian troops away from the invasion of France, had to be abandoned because the navy lacked the heavy weapons required to make a successful landing.

……

xxxxx…… The Franco-

xxxxx…… The Franco-

xxxxx…… As noted earlier, the French chemist and biologist Louis Pasteur -

xxxxx…… In response to his country’s military defeat, the composer Charles Gounod composed Gallia, a lamentation for solo soprano, chorus and orchestra. It was first performed in 1871.

xxxxxAs we shall see, the Franco-

xxxxxAs we shall see, the Franco-

Vb-

Including:

The Battle of Sedan