THE FRENCH REVOLUTION 1789 - 1799 (G3b)

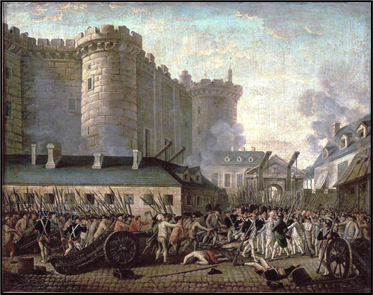

THE STORMING OF THE BASTILLE 14th JULY 1789

xxxxxAs we have seen, after the recall of the States General in 1788, and some bitter infighting between its three estates (the nobles, clergy and commoners), the National Constituent Assembly had been formed with power in the hands of the people. By this time, however, there was much unrest throughout the country, and when, in July 1789, Louis XVI sent troops into Paris and Versailles, the capital erupted. Thousands took to the streets and, on the 14th, stormed and captured the Bastille, a prison which was a symbol of Bourbon oppression. At the same time, rebellion broke out across the land. Early the next month the Assembly swept away the feudal system, together with the government taxes, and began working on its Declaration, aimed to give all men their basic freedoms, and to make France a sovereign nation owned by its people. Meanwhile, the statesman and soldier Lafayette formed the National Guard with its tricolour and its call for “Liberty, Equality and Fraternity”. In the October, however, another mob was on the march. Fearing that Louis was plotting to regain power, and near to starvation, a huge body of Parisians, mainly woman, marched on Versailles and brought the king, his family and his court back to the capital. As we shall see, virtually a prisoner of the state, in 1791 Louis planned an escape, with dire consequences. By then the country, and Paris in particular, were in the hands of fanatics like Marat, Danton and Robespierre.

Acknowledgements

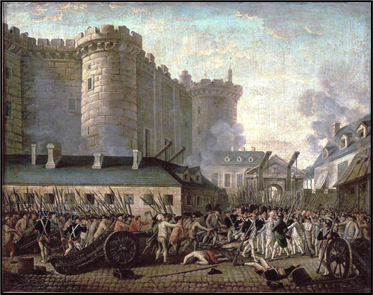

Revolution: date and artist unknown. Bastille: date and artist unknown – Château de Versailles, France. March: illustration, artist unknown - National Library of France, Paris.

Including:

An Outline of the

French Revolution

1789-1792

xxxxxAs we have seen, after Louis XVI was forced to recall the States General in 1788, power eventually came to reside in the National Constituent Assembly, a body made up of the three estates of the realm - the nobility, higher clergy and the commoners. By dint of their increased numbers, and the support of the more liberal-minded members from the privileged classes, the commoners had a decided majority in this new assembly. However, given the state of the country, the task of creating a new political and social order proved as difficult, if not more so, as the overthrow of the Ancien Régime had been. There was a lack of practical experience within its membership, and divergent views as to how best this colossal undertaking could be achieved. In the meantime, however, exhilarated by the promise of reform, the mass of the people grew impatient for change. More violent disturbances broke out in Paris, and in many other parts of the country, where the uprisings amongst the peasants came to be known as the Grande Peur (the Great Fear).

xxxxxAs we have seen, after Louis XVI was forced to recall the States General in 1788, power eventually came to reside in the National Constituent Assembly, a body made up of the three estates of the realm - the nobility, higher clergy and the commoners. By dint of their increased numbers, and the support of the more liberal-minded members from the privileged classes, the commoners had a decided majority in this new assembly. However, given the state of the country, the task of creating a new political and social order proved as difficult, if not more so, as the overthrow of the Ancien Régime had been. There was a lack of practical experience within its membership, and divergent views as to how best this colossal undertaking could be achieved. In the meantime, however, exhilarated by the promise of reform, the mass of the people grew impatient for change. More violent disturbances broke out in Paris, and in many other parts of the country, where the uprisings amongst the peasants came to be known as the Grande Peur (the Great Fear).

xxxxxAt this stage, had the Assembly and monarchy worked together, a means may have been found to calm the situation. Instead of that, Louis sent in the troops to restore his authority. Giving way to pressure from his wife, Marie Antoinette, and his brother, the Count of Artois, he drafted several foreign regiments into Paris and Versailles. In fact, this only served to make matters worse. Fear grew among the rioters that this was but a preliminary step to dissolving the Assembly, and the abrupt dismissal of Jacques Necker, the finance minister, on the 11th July 1789 only served to confirm their fears. The following day Paris erupted into open rebellion. Thousands of its citizens armed themselves and, two days later, stormed and captured the Bastille, the gloomy royal stronghold which was a symbol of the despotic rule of the Bourbons. Its seven prisoners were released, its small garrison was brutally slaughtered, and the building was virtually razed to the ground. Almost at the same time, rebellion on a much wider scale than earlier broke out in towns and villages across the land, fuelled in part by the failure of the 1788 harvest, and the consequent shortage of food. On hearing about the attack on the Bastille, the king is said to have remarked that it was a “great revolt”. “No Sire”, replied one of his courtiers, “it is a great revolution”. And so it proved to be.

xxxxxAt this stage, had the Assembly and monarchy worked together, a means may have been found to calm the situation. Instead of that, Louis sent in the troops to restore his authority. Giving way to pressure from his wife, Marie Antoinette, and his brother, the Count of Artois, he drafted several foreign regiments into Paris and Versailles. In fact, this only served to make matters worse. Fear grew among the rioters that this was but a preliminary step to dissolving the Assembly, and the abrupt dismissal of Jacques Necker, the finance minister, on the 11th July 1789 only served to confirm their fears. The following day Paris erupted into open rebellion. Thousands of its citizens armed themselves and, two days later, stormed and captured the Bastille, the gloomy royal stronghold which was a symbol of the despotic rule of the Bourbons. Its seven prisoners were released, its small garrison was brutally slaughtered, and the building was virtually razed to the ground. Almost at the same time, rebellion on a much wider scale than earlier broke out in towns and villages across the land, fuelled in part by the failure of the 1788 harvest, and the consequent shortage of food. On hearing about the attack on the Bastille, the king is said to have remarked that it was a “great revolt”. “No Sire”, replied one of his courtiers, “it is a great revolution”. And so it proved to be.

xxxxxIn itself, the storming of the Bastille was by no means a military feat, even though achieved by a disorganised mob, but, like the shot fired at Lexington in 1775 at the start of the American War of Independence, it was heard around the world. For many it meant the beginning of a new, democratic age. For the English statesman Charles Fox, for example, a champion of liberty, it was “the greatest event that ever happened in the world”, and the English romantic poet William Wordsworth thought it was bliss to be alive at the dawn of such a day. But whilst they and many others waxed lyrical - and not without good cause - others were far from euphoric. Thousands of French nobility and higher clergy packed their bags and left the country - émigrés hoping one day to return -, whilst a number of European governments, particularly those of Austria, Prussia, Russia and Great Britain, viewed the civil disturbances with a great deal of concern and apprehension.

xxxxxEarly the next month the Assembly swept away all that remained of the French feudal system, its medieval concept of serfdom, and the dues and services it had demanded from its peasants. And the dreaded taille and tithe were also abolished. In future taxes were to be levied by popular consent. Then towards the end of the month it began work on its Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. This was to claim that all men had the right to be free, the right to own property, the right to religious toleration, the right to speak their mind and the right to resist oppression. France, it was to declare, was not the private property of its monarch, but a sovereign nation owned by its people. The American influence was unmistakable, save that, in the French case, a limited monarchy, a mere shadow of its former self, was to be retained.

xxxxxEarly the next month the Assembly swept away all that remained of the French feudal system, its medieval concept of serfdom, and the dues and services it had demanded from its peasants. And the dreaded taille and tithe were also abolished. In future taxes were to be levied by popular consent. Then towards the end of the month it began work on its Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. This was to claim that all men had the right to be free, the right to own property, the right to religious toleration, the right to speak their mind and the right to resist oppression. France, it was to declare, was not the private property of its monarch, but a sovereign nation owned by its people. The American influence was unmistakable, save that, in the French case, a limited monarchy, a mere shadow of its former self, was to be retained.

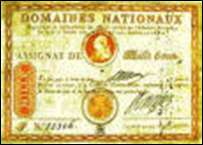

xxxxxAnd under guidelines put forward by the Comte de Mirabeau, the Assembly also introduced severe restrictions on the authority of the Roman Catholic Church by a series of measures called the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. These virtually transformed the Catholic Church into a national institution. Indeed, one of these articles went so far as to confiscate all ecclesiastical estates, making up about one tenth of all France. On the strength of these lands, a new form of currency was issued called assignats and, for a time, these averted the danger of bankruptcy, though inflation was well under way by the end of 1791.

xxxxxAnd under guidelines put forward by the Comte de Mirabeau, the Assembly also introduced severe restrictions on the authority of the Roman Catholic Church by a series of measures called the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. These virtually transformed the Catholic Church into a national institution. Indeed, one of these articles went so far as to confiscate all ecclesiastical estates, making up about one tenth of all France. On the strength of these lands, a new form of currency was issued called assignats and, for a time, these averted the danger of bankruptcy, though inflation was well under way by the end of 1791.

xxxxxBut in October 1789 this National Guard - a defence force which was being developed countrywide - could not stop another violent demonstration of the people’s power, though it did save the royal family from bodily harm. In that month, suspicious of what the king might be plotting, and enflamed by a rumour that he was intercepting grain carts outside Paris in order to starve the city into submission, a mob, made up mostly of women and many weak with hunger, marched on Versailles. There they forced the king, his family, and his court out of their luxurious apartments, and escorted them in triumph back to Paris. On arrival they were housed in the Tuileries Palace, whilst the National Assembly - also moving to the capital - took up residence in a riding school within the grounds. Louis was virtually a hostage of his people and, as events were shaping, was likely to remain so.

xxxxxBut in October 1789 this National Guard - a defence force which was being developed countrywide - could not stop another violent demonstration of the people’s power, though it did save the royal family from bodily harm. In that month, suspicious of what the king might be plotting, and enflamed by a rumour that he was intercepting grain carts outside Paris in order to starve the city into submission, a mob, made up mostly of women and many weak with hunger, marched on Versailles. There they forced the king, his family, and his court out of their luxurious apartments, and escorted them in triumph back to Paris. On arrival they were housed in the Tuileries Palace, whilst the National Assembly - also moving to the capital - took up residence in a riding school within the grounds. Louis was virtually a hostage of his people and, as events were shaping, was likely to remain so.

xxxxxBy now the mob were being led by a number of fanatical revolutionaries, men like Danton, Marat and Robespierre, who, for the cause they believed in or simply for their own personal gain, were busy fanning the flames of a Revolution, already burning brightly. As we shall see, when, in 1791, the king attempted to make a bolt for it, events were to turn extremely ugly.

xxxxxIncidentally, as one would expect, many comparisons have been made between the American and French Revolutions. One of the most glaring differences was the conditions under which their new systems of government were devised. In the case of the colonists, a small number of highly qualified men drew up the American constitution behind closed doors in the peaceful city of Philadelphia. In France, by contrast, the creation of a new political and social order was carried out by a large body of relatively inexperienced “politicians”, in a city seething with revolt, and in a country on the verge of social and economic collapse. In these circumstances, the events that followed were highly likely, if not inevitable. ……

xxxxx…… Inxthe course of time a large number of histories of the French Revolution have been written. To mention but two, the French statesman and historian Adolphe Thiers (1797-1877) completed his version in 1827, and the Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle published his ten years later.

Meanwhile, under the leadership of General Lafayette (1757-1834), the French hero who, as we have seen, had actually fought for American independence, the army in Paris was formed into the National Guard. Its tricolour flag, designed by Lafayette himself, replaced the Bourbon fleur de lys, and “Liberty, Equality and Fraternity” became its slogan, and that of revolutionary France.

An Outline of the French Revolution 1774 - 1792

|

1774

|

May

|

Louis XVI accedes to the throne. Country in turmoil and near to bankruptcy.

|

|

1774 -

1787

|

|

A series of finance ministers, including Turgot, Necker and Calonne, attempts to introduce a tax system which includes nobility and upper clergy.

|

|

1787

|

|

Following costly support for the colonists in the American War of Independence, (ended 1783) banks refuse to provide further loans. France is declared bankrupt.

|

|

1788

|

August

|

Amid growing unrest, Louis calls an election for a States General (Parliament).

|

|

1789

|

May

|

Meeting of the States General made up of the Three Estates - Nobility, Upper Clergy and Commoners - breaks up in deadlock over voting power.

|

|

|

June

|

Oath of Tennis Court by Third Estate leads to the formation of the National Constituent Assembly with Commoners in the majority.

|

|

|

July

|

Further disorder - King sends troops into Paris and Versailles.

14th - Storming of the Bastille - start of the French Revolution.

Peasant rebellion - “Great Fear” - in the provinces.

|

|

|

October

|

Reforms begin based on Liberty, Equality and Fraternity. Feudal system is abolished, the Church is nationalised, and new currency is issued (assignate).

|

|

|

|

Violence breaks out again. Hungry mob brings royal family to Paris.

|

|

1790

|

July

|

Louis accepts new constitution, literally reducing monarch to a figure head.

|

|

1791

|

June

|

Royal family attempts to escape -The Flight to Varennes - but is arrested.

|

|

|

July

|

Mass demonstration against the king is put down by force -

the Massacre of the Champs-de-Mars.

|

|

|

August

|

By the Declaration of Pillnitz, Austria and Prussia threaten to attack France.

|

|

|

September

|

Louis again accepts the new constitution and is reinstated as monarch.

|

|

1792

|

April

|

France declares war on Austria and begins the Revolutionary Wars.

La Marseillaise is composed by Claude Joseph Roget de Lisle.

|

G3b-1783-1802-G3b-1783-1802-G3b-1783-1802-G3b-1783-1802-G3b-1783-1802-G3b

xxxxx

xxxxx xxxxx

xxxxx xxxxx

xxxxx xxxxx

xxxxx xxxxx

xxxxx