FREDERICK (II) THE GREAT OF PRUSSIA

1740 -

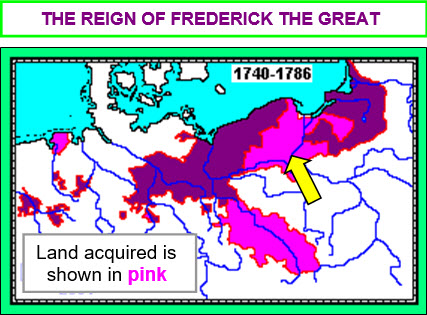

xxxxxFrederick II succeeded his

father, Frederick William, in 1740 and, as we have seen, plunged his

country into the War of the Austrian Succession. His successful

retention of the wealthy province of Silesia, however, led to the

Seven Years' War in which the Austrian leader, Maria Theresa, had

assembled a powerful alliance, including France, to thwart Prussia's

territorial ambitions. Opening the war with a surprise attack upon

Saxony, Frederick's skill as a military commander brought a series

of victories against the French, Austrians and Russians, but by 1759 the strength of the

opposition began to tell, and all seemed lost. However, in 1761 the

new Russian leader, Peter III, withdrew his forces from the war, and

the British, his only ally, began to hold the French in check.

Austria then became isolated and agreed to come to terms. By the

Treaty of Paris in 1763 (G3a) Prussia retained the coveted province of Silesia, and

emerged as one of Europe’s most powerful nations. Later, in 1772 (G3a), as we shall see, Frederick went on to acquire western

Prussia in the First Partition of Poland, and, in 1785, to form the League of German Princes, the

first attempt by Prussia to assert its leadership over Germany. In

domestic politics, he proved, indeed, the prototype of the

"Enlightened Despot". As the "first servant" of the state, he

introduced improvements in the law, education and agriculture, and

encouraged manufacturing industry. And he made some limited progress

towards the right of the individual in such matters as free speech

and religious toleration. A man of culture himself, he patronized

the arts and sciences throughout his life. At his death, he left an

efficient, well-

xxxxxAs we have seen, with the death of Emperor

Charles VI in 1740, and the succession of his daughter Maria Theresa,

a number of states, including Prussia, saw the Habsburg dominions as

up for grabs. Frederick II, who had succeeded his father Frederick

William earlier that year, lost no time in making the first move in a

struggle which came to be known as the War of the Austrian Succession.

He invaded Austria, and within less than two years had captured the

wealthy province of Silesia, an acquisition which was confirmed by the

Treaty of Aix-

xxxxxAs we have seen, with the death of Emperor

Charles VI in 1740, and the succession of his daughter Maria Theresa,

a number of states, including Prussia, saw the Habsburg dominions as

up for grabs. Frederick II, who had succeeded his father Frederick

William earlier that year, lost no time in making the first move in a

struggle which came to be known as the War of the Austrian Succession.

He invaded Austria, and within less than two years had captured the

wealthy province of Silesia, an acquisition which was confirmed by the

Treaty of Aix-

xxxxxThe time came in 1756, with the outbreak of the

Seven Years’ War. By then, however, it was not Marie Theresa of

Austria who found the odds stacked against her, but Frederick of

Prussia. Anticipating the coming conflict, the Austrian leader had

reversed her country's traditional policy by making an alliance with

France (the so called "Diplomatic Revolution"), and this pact was

joined by Russia, Sweden and Saxony, all anxious to thwart Prussia's

territorial ambitions. Threatened and isolated -

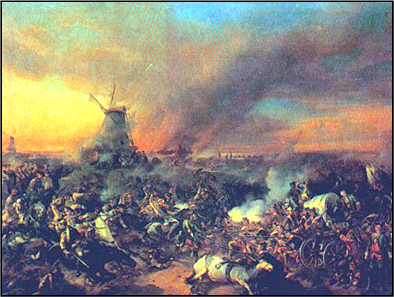

xxxxxIn the first stages of the struggle, the

Prussians did well, due in large measure to Frederick's skill as a

military commander. They were defeated by the Austrians at the Battle

of Kolin, but then went on to gain victories over the French at

Rossbach, the Austrians at Leuthen, and the Russians at Zorndorf (illustrated). But by 1759

the tide had begun to turn. Attacked on a number of fronts,

Frederick's forces were badly defeated at the Battles of Kay and

Kundersdorf, and the following year they were overwhelmed at Landshut.

By October 1760, eastern Prussia had been taken, and Russian and

imperial troops were in Berlin. But when all seemed lost, victory was

snatched from the jaws of defeat. The timely death of the Empress of

Russia, Elizabeth Petrovna, brought Peter III to the throne and he, a

staunch admirer of the Prussian leader, lost no time in signing a

peace agreement. In addition, the British and Hanovarians at last

began to make their presence felt on the battlefield, keeping the

French in check. By the terms of the Treaty of Paris in 1763

(G3a), Prussia, its possession of Silesia endorsed, emerged

as one of Europe's most powerful countries, and Frederick as one of

its most successful leaders.

xxxxxIn the first stages of the struggle, the

Prussians did well, due in large measure to Frederick's skill as a

military commander. They were defeated by the Austrians at the Battle

of Kolin, but then went on to gain victories over the French at

Rossbach, the Austrians at Leuthen, and the Russians at Zorndorf (illustrated). But by 1759

the tide had begun to turn. Attacked on a number of fronts,

Frederick's forces were badly defeated at the Battles of Kay and

Kundersdorf, and the following year they were overwhelmed at Landshut.

By October 1760, eastern Prussia had been taken, and Russian and

imperial troops were in Berlin. But when all seemed lost, victory was

snatched from the jaws of defeat. The timely death of the Empress of

Russia, Elizabeth Petrovna, brought Peter III to the throne and he, a

staunch admirer of the Prussian leader, lost no time in signing a

peace agreement. In addition, the British and Hanovarians at last

began to make their presence felt on the battlefield, keeping the

French in check. By the terms of the Treaty of Paris in 1763

(G3a), Prussia, its possession of Silesia endorsed, emerged

as one of Europe's most powerful countries, and Frederick as one of

its most successful leaders.

xxxxxIn surviving as a nation,

Prussia had paid a high price in both men -

xxxxxNot surprisingly,

Frederick also made use of this long period of peace to increase the

strength and quality of his army. By the end of his reign, he had

doubled its size to 190,000, and created a well-

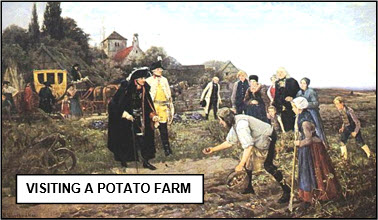

xxxxxIncluded in this progressive programme were

improvements in agriculture, such as the introduction of crop rotation

and the scientific methods of cattle breeding; the construction of

canals and the draining of marshland, notably in the valleys of the

Oder and Vistula; and the encouragement of manufacturing industry,

like the production of porcelain, silk and tobacco. He also began a

system of compulsory education for children of five to fourteen years

of age, and, in order to increase the nation's population, welcomed

immigrant farmers from all over Europe. And he made, too, a valuable

contribution to law reform. In 1747 he issued a new codification of

Prussian law, known as the Codex Fridericianus,

and this served as a basis for the revised code of 1794.

xxxxxIncluded in this progressive programme were

improvements in agriculture, such as the introduction of crop rotation

and the scientific methods of cattle breeding; the construction of

canals and the draining of marshland, notably in the valleys of the

Oder and Vistula; and the encouragement of manufacturing industry,

like the production of porcelain, silk and tobacco. He also began a

system of compulsory education for children of five to fourteen years

of age, and, in order to increase the nation's population, welcomed

immigrant farmers from all over Europe. And he made, too, a valuable

contribution to law reform. In 1747 he issued a new codification of

Prussian law, known as the Codex Fridericianus,

and this served as a basis for the revised code of 1794.

xxxxxFrederick patronized the arts and sciences all his life, and was himself a cultured man. He was interested in literature, wrote poetry, composed music, played the flute, and was a student of philosophy, history and politics. He corresponded with famous intellectuals of his day and, until they fell out, had Voltaire as a member of his court. He was also a prolific writer and, amongst many works, wrote History of My Time, The Art of War, and Antimachiavel, a work in which he roundly condemned despotic rule. As an "enlightened" despot, he made some limited progress towards the rights of the individual. Torture was abolished save for murder and treason, some freedom of speech was permitted, and all forms of religious opinion were tolerated.

xxxxxThis said, he placed much reliance upon the aristocracy (or Junkers), regarding them as the backbone of the state. As such, they enjoyed a large degree of autonomy within their estates, and it is more than likely that some of Frederick's progressive innovations never reached the lower levels of society. Certainly the serfs remained very much tied to their master's estates.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

xxxxxBy the standards of the day, Frederick was

indeed an enlightened ruler who set new standards by which to measure

the value of kingship. Intelligent, energetic, and dedicated to his

calling, he won the admiration and the affection of the vast majority

of his subjects, and was known by many as "Old Fritz". And by his

efforts, he left behind, a nation which had doubled in size and

trebled in population; a treasury that was full to over-

xxxxxBy the standards of the day, Frederick was

indeed an enlightened ruler who set new standards by which to measure

the value of kingship. Intelligent, energetic, and dedicated to his

calling, he won the admiration and the affection of the vast majority

of his subjects, and was known by many as "Old Fritz". And by his

efforts, he left behind, a nation which had doubled in size and

trebled in population; a treasury that was full to over-

xxxxxIncidentally,

Adolf Hitler (illustrated), Germany's leader

(fuhrer) in the Second World War, was a

great admirer of Frederick the Great. Indeed, in his last weeks, spent

in a Berlin bunker in 1945, his propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels,

used to read to him passages from Carlyle's history

of his hero. Then, as Soviet troops came ever nearer to Berlin, Hitler

had Frederick's body, and that of his father, taken from Potsdam and

hidden in a salt mine in Thuringia. After the war both bodies were

taken to the Hohenzollern family home near Stuttgart, but in August

1991 the German government removed them and again put them to rest at

Sans Souci (French for “carefree”).

xxxxxIncidentally,

Adolf Hitler (illustrated), Germany's leader

(fuhrer) in the Second World War, was a

great admirer of Frederick the Great. Indeed, in his last weeks, spent

in a Berlin bunker in 1945, his propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels,

used to read to him passages from Carlyle's history

of his hero. Then, as Soviet troops came ever nearer to Berlin, Hitler

had Frederick's body, and that of his father, taken from Potsdam and

hidden in a salt mine in Thuringia. After the war both bodies were

taken to the Hohenzollern family home near Stuttgart, but in August

1991 the German government removed them and again put them to rest at

Sans Souci (French for “carefree”).

Acknowledgements

Frederick II: detail, by the

Swiss portrait painter Anton Graff (1736-

G2-