xxxxxThe

experienced explorer Sir John Franklin set out to find the

Northwest Passage in 1845.

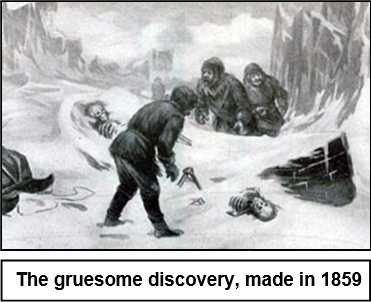

His expedition, made up of two ships and a crew of 128, made it as

far as Lancaster Sound, but then was never seen again. Many search

missions were sent out, but it was not until 1859 that the bodies

of some of the crew were found on King William Island. An account

of the voyage, found on one of the men, revealed that the

expedition had reached Victoria Sound, about half way between the

Atlantic and the Pacific, but that the ships had then become ice-

SIR JOHN FRANKLIN 1786 -

Acknowledgements

Franklin: detail,

lithograph by the Belgium printmaker Louis Haghe (1806-

xxxxxJohn Franklin joined the Royal Navy as a lad of 14,

and the following year was a member of the expedition, led by his

cousin Matthew Flinders, which circumnavigated Australia. He

returned in time to serve in the Battle of Trafalgar, and after an

abortive attempt to reach the North Pole in 1818, he led two

expeditions across Canada during the 1820s, travelling from the

western shore of Hudson Bay to the Arctic Ocean, and then

exploring Canada’s north-

xxxxxJohn Franklin joined the Royal Navy as a lad of 14,

and the following year was a member of the expedition, led by his

cousin Matthew Flinders, which circumnavigated Australia. He

returned in time to serve in the Battle of Trafalgar, and after an

abortive attempt to reach the North Pole in 1818, he led two

expeditions across Canada during the 1820s, travelling from the

western shore of Hudson Bay to the Arctic Ocean, and then

exploring Canada’s north-

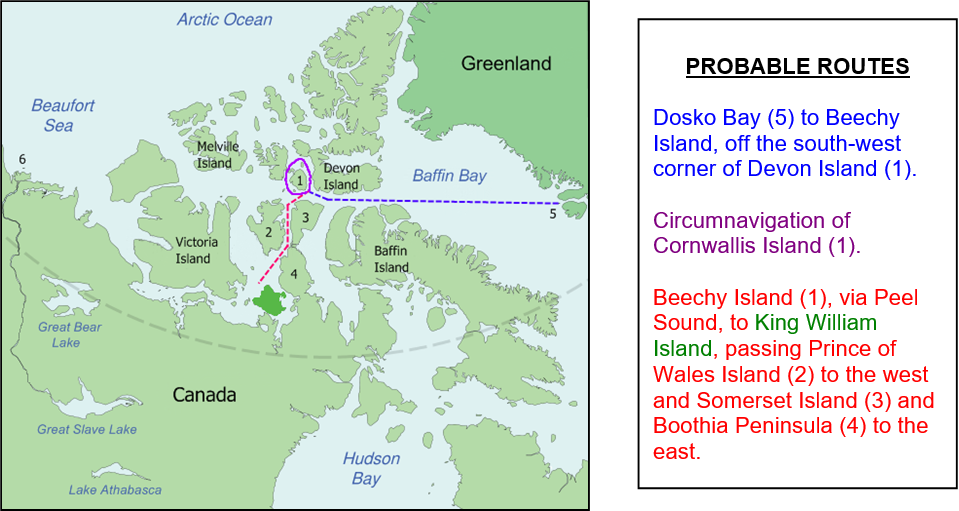

xxxxxBut Franklin’s days as an explorer were not over. Because of his wealth of experience in arctic regions, and his proven leadership qualities, in 1844 he was chosen by the British Admiralty to lead yet another expedition in search of the allusive Northwest Passage, aimed at opening a route from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean via an arctic waterway north of Canada. In May of 1845 he sailed from England with two ships, the Erebus and the Terror, and a crew of 128 officers and men. They reached the entrance to Lancaster Sound two months later, where they were sighted by British whalers hunting north of Baffin Island, but after that they were never seen again.

xxxxxWhat actually befell that ill-

xxxxxWhat actually befell that ill-

xxxxxAccording

to this account, the expedition had wintered at Beechey Island

over the winter of 1845-

Including:

The Arctic

and Antarctica

Va-

xxxxxIncidentally, an investigation into the tragedy suggested that

during their fatal march south some of the crew had resorted to

cannibalism, eating the flesh of men who had died en route. And

post-

xxxxxNotxsurprisingly, the fate

of Franklin’s expedition focused attention once again on the

Northwest Passage, that

route across The Arctic

which the best of navigators, including John Cabot, Martin

Frobisher, John Davis, Henry Hudson and William Baffin, had failed

to achieve. The

first man to make the crossing, in fact, was the Irish explorer Robert McClure (1807-

xxxxxNotxsurprisingly, the fate

of Franklin’s expedition focused attention once again on the

Northwest Passage, that

route across The Arctic

which the best of navigators, including John Cabot, Martin

Frobisher, John Davis, Henry Hudson and William Baffin, had failed

to achieve. The

first man to make the crossing, in fact, was the Irish explorer Robert McClure (1807-

xxxxxThexNortheast

Passage, which was attempted among others by Richard Chancellor,

Willem Barents and Henry Hudson, was conquered much earlier. After

making two preparatory voyages in the mid-

xxxxxAs we have seen, an attempt to reach the North Pole

was made as early as 1806 by the English whaler William Scoresby.

He reached within 510 miles of the pole. Then the English explorer

William Parry penetrated even further in 1827 and, four years

later the Englishman James Clark Ross discovered the north

magnetic pole. Thexnext attempt was not

made until 1879. Led by an

American naval officer, George Washington

Delong (1844-

xxxxxAs we have seen, an attempt to reach the North Pole

was made as early as 1806 by the English whaler William Scoresby.

He reached within 510 miles of the pole. Then the English explorer

William Parry penetrated even further in 1827 and, four years

later the Englishman James Clark Ross discovered the north

magnetic pole. Thexnext attempt was not

made until 1879. Led by an

American naval officer, George Washington

Delong (1844-

xxxxxFourxyears later a Swedish

engineer named Salomon

August Andrée

(1854-

xxxxxFourxyears later a Swedish

engineer named Salomon

August Andrée

(1854-

xxxxxDuring the late 1830s expeditions were sent to Antarctica by France, Britain and the United States, led respectively, as we have seen, by Jules Dumon d’Urville, James Clark Ross, and Charles Wilkes. However, until the turn of the century there was no intensive exploration in the region, nor any serious attempt to reach the South Pole. The main activity was seal and whale hunting on the fringes of the continent. Then, during the first decade of the 20th century a number of explorers led national expeditions into the interior, including the Englishman Robert Falcon Scott, the Scotsman Ernest Henry Shackleton, the German Erich von Drygalski, and the Frenchman Jean Baptiste Charcot. In 1909 Shackleton came within 97 nautical miles of the pole.