xxxxxAs we have

seen, in 1882 the

British, the masters of Egypt, decided to withdraw the Egyptian

troops from the Sudan, then in a state of rebellion. There

followed the siege of Khartoum and the killing of General Gordon

and his garrison. In the late 1890s, however, fearing that other

colonial powers, particularly the French, might seize the

headwaters of the Nile - vital to Egypt’s survival - the

British decided to re-conquer the Sudan. This was achieved by

General Kitchener at the Battle of Omdurman in September 1898, but by then the French

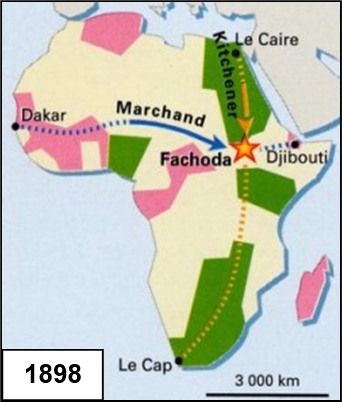

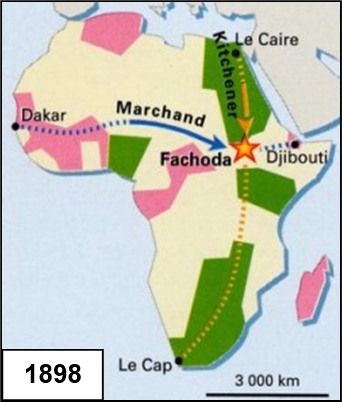

had put into operation a plan to unite their African colonies from

west to east, thereby stopping the British from achieving a

similar project north to south. Furthermore, with the support of

the Ethiopians they planned to invade the Sudan and threaten Egypt

by gaining control of the upper waters of the Nile. In July 1898 a small French force,

led by Captain Marchand, crossed Africa from Senegal and, reaching

Fashoda in the Sudan, claimed the area around the White Nile as a

French protectorate. Kitchener, fresh from his victory at

Omdurman, assembled a sizeable force and, travelling by boat,

reached Fashoda in the September, but Marchand refused to vacate

the area, and there followed a diplomatic row between France and

Britain which almost led to a full-scale war. Eventually,

however, the French realised that they were at a military

disadvantage, and their troops were withdrawn. The “Fashoda

Incident” caused ill-feeling between the two countries, but

the fact that the crisis was solved diplomatically proved a

turning point in Anglo-French relations, and, because of the

growing might of Germany, it actually led to the Entente

Cordiale of 1904.

xxxxxAs

we have seen, after the British took over control of Egypt in 1882, following the Battle of

Tel el Kebir, the British government decided that the Egyptian

garrisons in the Sudan should be withdrawn. It was considered that

this vast country to the south of Egypt, then in the throes of a

rebellion by a religious fanatic, would be too expensive to pacify

and too difficult to administer. It was during this withdrawal that

Khartoum, the capital, was besieged by the Mahdists and General

Charles Gordon and his garrison of 7,000 men were slaughtered when

the city was finally entered in January 1885.

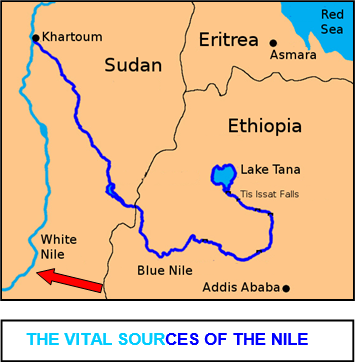

xxxxxTowards

the end of the century, however, the British were forced to change

this decision. Other European nations - such as Belgium, Italy

and France - were beginning to see the Sudan - not yet

colonized - as an area for occupation and exploitation. This

alarmed the British government. If the Sudan were invaded and

occupied, then the headwaters of the Nile, so vital to the political

and economic stability of Egypt, would be in the hands of - and

under the control of - a foreign power. It was for this reason

that in March 1896 a large army commanded by General Herbert

Kitchener was ordered to invade and re-conquer the Sudan. It

was not until September 1898, however, that the victory at the Battle of Omdurman virtually secured the

country for the British and by then it was too late. A French

contingent had already arrived at Fashoda on the White Nile and

claimed the area as a French protectorate.

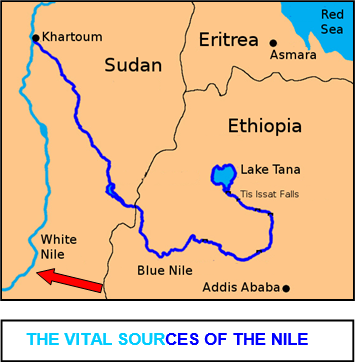

xxxxxFor

some years the French had shown an interest in the African coastline

along the Red Sea following French exploration of the area in the

mid-19th century. In the 1880s they entered into trade

agreements with a succession of Somali Sultans and, as a result,

were granted a protectorate (French Somaliland) over the area known

as Djibouti on the Gulf of Tadjoura. Then in 1896 their interest in the region was further heightened.

In that year, as we have seen, they gave advice and war equipment to

the Ethiopians, and this helped them to defeat an Italian invasion

at the Battle of Adowa. In recognition of their assistance, their

neighbours allowed them to use Ethiopia as a staging ground for

incursions into southern Sudan. It was at this point that the French

conceived the idea of laying on a military expedition that would

march from West Africa - where they already had sizeable

possessions - to Fashoda in southern Sudan, an ideal location

for the building of a dam to

divert - and thereby reduce - the upper waters of the

White Nile. Such a project, they anticipated, would link French

possessions across Africa from west to east (from the Niger to the

Nile); prevent the British from joining up their territories from

north to south (Cairo to Cape Town) - the life-long dream,

as we have seen, of the British diamond magnate Cecil Rhodes -

and possibly, by impeding the flow of the Nile, force the British

out of Egypt. Thus the small settlement of Fashoda, by being at the

point where the colonial ambitions of Britain and France crossed and

clashed (see map), was set to become the centre of a major

international crisis.

xxxxxThexNile

Expedition, led by Captain Jean-Baptiste

Marchand (illustrated),

and made up of seven French officers and

120 Senegalese infantry, set out from Dakar on its ambitious and

arduous mission in June 1897. It travelled up the Congo as far as

Bangui, and then after a mammoth 14 month trek by foot and boat

across the heart of Africa - much of the territory

unchartered - the small contingent reached Fashoda in July 1898. There it raised the French flag and

set about repairing the town’s dilapidated fort. According to a

pre-arranged plan, it was due to meet up with two expeditions

coming from the east, across Ethiopia, but neither turned up.

Instead, in September Marchand was faced with the arrival of a

sizeable Anglo-Egyptian force aboard five steamers. Having

learnt from one of the Mahdist prisoners that a small French

contingent had arrived at Fashoda, General Kitchener had quickly

assembled a powerful flotilla and set off to put into effect what

the re-conquest of the Sudan had all been about - the

safeguarding of the upper waters of the Nile. But Marchand

politely told the British commander that he was staying put.

Kitchener, showing a great deal of restraint (especially since he

had overwhelming superiority in manpower and firepower), raised

the Union Jack alongside the Tricolour, set up camp, and left the

politicians to sort it out.

xxxxxThexNile

Expedition, led by Captain Jean-Baptiste

Marchand (illustrated),

and made up of seven French officers and

120 Senegalese infantry, set out from Dakar on its ambitious and

arduous mission in June 1897. It travelled up the Congo as far as

Bangui, and then after a mammoth 14 month trek by foot and boat

across the heart of Africa - much of the territory

unchartered - the small contingent reached Fashoda in July 1898. There it raised the French flag and

set about repairing the town’s dilapidated fort. According to a

pre-arranged plan, it was due to meet up with two expeditions

coming from the east, across Ethiopia, but neither turned up.

Instead, in September Marchand was faced with the arrival of a

sizeable Anglo-Egyptian force aboard five steamers. Having

learnt from one of the Mahdist prisoners that a small French

contingent had arrived at Fashoda, General Kitchener had quickly

assembled a powerful flotilla and set off to put into effect what

the re-conquest of the Sudan had all been about - the

safeguarding of the upper waters of the Nile. But Marchand

politely told the British commander that he was staying put.

Kitchener, showing a great deal of restraint (especially since he

had overwhelming superiority in manpower and firepower), raised

the Union Jack alongside the Tricolour, set up camp, and left the

politicians to sort it out.

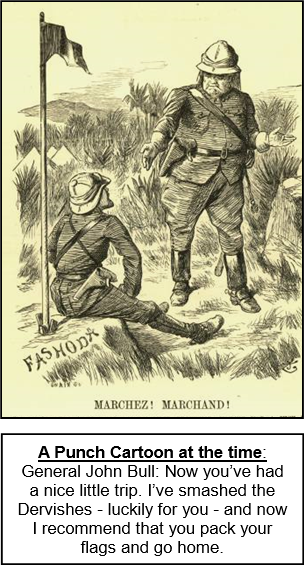

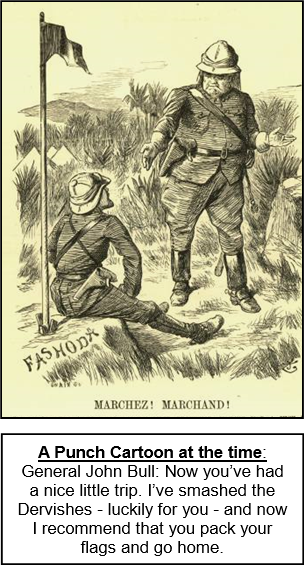

xxxxxThe

military confrontation at Fashoda led to several weeks of intense

negotiation between London and Paris, and public outrage in both

countries reached to fever pitch. In October both nations began to

mobilize their navies in preparation for war. The British claimed

that the Sudan was an Egyptian protectorate and that, by their

victory over the Sudanese at the Battle of Omdurman, they had re-conquered

the country for the Khedive. The French argued that they had every

right to possess the Upper Nile region because the British had

failed to achieve an “effective occupation”, a requirement laid down

by the Berlin Conference of 1884. What eventually brought about a settlement, however,

was the practical realisation on the part of the French that they

were not in a position to win in the dispute. Their army was far

larger than that of the British, but it would have to be

transported, and this would be a hazardous operation given the

strength of the British navy. Furthermore, at ground zero - the

area under dispute - the small French force would quickly be

overwhelmed. And there was, too, a wider consideration. France was

growing ever more concerned about the growing might of her land

neighbour Germany. This was not the time to involve the country in a

colonial war about a remote corner somewhere in Africa. On the 3rd

November the French government ordered Major Marchand (promoted soon

after arriving at Fashoda) to withdraw from the Sudan and return to

France via Djibouti. He was much aggrieved at the decision, but he

was obliged to obey.

xxxxxThe settlement of the

Fashoda crisis put an end to what came to be called “the race for

the Nile”. There were three losers. Firstly, the French failed in

their bid to establish a continuous band of colonies across Africa -

aided and abetted by Ethiopia, their friend of convenience -, a

move that would have enhanced their own position in Africa and, at

the same time, curbed the power of Britain, their colonial rival.

Secondly, there were the Russians, who as allies of the French, had

themselves been drawn into the affairs of Ethiopia. They were never

to realise their dream of gaining a foothold in Africa at the mouth

of the Red Sea as a counterweight to Britain’s control of Egypt and

the Suez Canal, and as a possible launching pad for a colonial

future in Africa. And thirdly, there were the Ethiopians. Fresh from

their great victory over the Italians at the Battle of

Adowa, they embarked on territorial

expansion in 1897 and by July had reached the White Nile and raised

the Ethiopian flag alongside that of the French – their position arrowed on map above. But the

capitulation of the French over Fashoda put an end to such grand

ideas. In March 1902 the Ethiopian leader, Menelik II, was obliged

to sign a treaty with Great Britain in which he renounced any claims

to the east bank of the Nile, and pledged not to redirect any waters

of the Nile’s tributaries without British permission. The sources of

the Nile which, in the words of the young Winston Churchill, “are as

much an integral part of Egypt as the roots are an integral part of

a tree”, were firmly under British control.

xxxxxThe settlement of the

Fashoda crisis put an end to what came to be called “the race for

the Nile”. There were three losers. Firstly, the French failed in

their bid to establish a continuous band of colonies across Africa -

aided and abetted by Ethiopia, their friend of convenience -, a

move that would have enhanced their own position in Africa and, at

the same time, curbed the power of Britain, their colonial rival.

Secondly, there were the Russians, who as allies of the French, had

themselves been drawn into the affairs of Ethiopia. They were never

to realise their dream of gaining a foothold in Africa at the mouth

of the Red Sea as a counterweight to Britain’s control of Egypt and

the Suez Canal, and as a possible launching pad for a colonial

future in Africa. And thirdly, there were the Ethiopians. Fresh from

their great victory over the Italians at the Battle of

Adowa, they embarked on territorial

expansion in 1897 and by July had reached the White Nile and raised

the Ethiopian flag alongside that of the French – their position arrowed on map above. But the

capitulation of the French over Fashoda put an end to such grand

ideas. In March 1902 the Ethiopian leader, Menelik II, was obliged

to sign a treaty with Great Britain in which he renounced any claims

to the east bank of the Nile, and pledged not to redirect any waters

of the Nile’s tributaries without British permission. The sources of

the Nile which, in the words of the young Winston Churchill, “are as

much an integral part of Egypt as the roots are an integral part of

a tree”, were firmly under British control.

xxxxxThe

ill-feeling between the Britain and France took some time to

die down. Indeed, the French were decidedly anti-British during

the Second Anglo-Boer War that began the following year.

However, a settlement of the Fashoda dispute in March 1899 by which

the French were allowed to expand eastward up to (but not including)

the Nile watershed, somewhat took the sting out of the dispute.

Furthermore, the fact that the two armies at Fashoda had not fought

each other on the spot, and that  the

matter had been eventually resolved by diplomatic means was a

turning point in Anglo-French relations. Given the changing

balance of power on the European continent, it paved the way for a

rapprochement between the two nations, the Entente

Cordiale of 1904. This eventually developed into a military

alliance against Germany in the First World War.

the

matter had been eventually resolved by diplomatic means was a

turning point in Anglo-French relations. Given the changing

balance of power on the European continent, it paved the way for a

rapprochement between the two nations, the Entente

Cordiale of 1904. This eventually developed into a military

alliance against Germany in the First World War.

xxxxxIn the Sudan, there was much to be done. Following the

final defeat of the Mahdist forces at the Battle of Umm Diwaykarat

in November 1899, work was begun on the administration of the

country. An Anglo-Egyptian Condominium was set up by which

sovereignty was jointly shared by the Khedive and

the British crown, though, in reality, the control of the country

was largely in the hands of the British. The executive power was

invested in a governor-general, nominated by the British

government, and his first task was to restore order throughout the

country. The northern region of the Sudan was pacified within a

short time, and steps were taken to modernise the administration,

but in the south the keeping of the peace proved the major task.

LordxKitchener served

as the first governor-general, but he was soon succeeded by General Sir Francis Reginald

Wingate (1861-1953)

(illustrated),

a man who knew the Sudan well and, like Lord

Cromer (1841-1917) in Egypt,

introduced reforms, encouraged development, and greatly improved the

lives of the ordinary people.

xxxxxIn the Sudan, there was much to be done. Following the

final defeat of the Mahdist forces at the Battle of Umm Diwaykarat

in November 1899, work was begun on the administration of the

country. An Anglo-Egyptian Condominium was set up by which

sovereignty was jointly shared by the Khedive and

the British crown, though, in reality, the control of the country

was largely in the hands of the British. The executive power was

invested in a governor-general, nominated by the British

government, and his first task was to restore order throughout the

country. The northern region of the Sudan was pacified within a

short time, and steps were taken to modernise the administration,

but in the south the keeping of the peace proved the major task.

LordxKitchener served

as the first governor-general, but he was soon succeeded by General Sir Francis Reginald

Wingate (1861-1953)

(illustrated),

a man who knew the Sudan well and, like Lord

Cromer (1841-1917) in Egypt,

introduced reforms, encouraged development, and greatly improved the

lives of the ordinary people.

xxxxxIncidentally, earlier in his career Major Jean-Baptiste

Marchand (1863-1934) had taken part in the French conquest of

Senegal, and in 1889 had been severely wounded during the capture of

Diena in Mali. He later fought with the French expedition to China

during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, and was promoted to the rank of general during the

First World War.

xxxxxThexNile

Expedition, led by Captain Jean-

xxxxxThexNile

Expedition, led by Captain Jean-

xxxxxThe settlement of the

Fashoda crisis put an end to what came to be called “the race for

the Nile”. There were three losers. Firstly, the French failed in

their bid to establish a continuous band of colonies across Africa -

xxxxxThe settlement of the

Fashoda crisis put an end to what came to be called “the race for

the Nile”. There were three losers. Firstly, the French failed in

their bid to establish a continuous band of colonies across Africa - the

matter had been eventually resolved by diplomatic means was a

turning point in Anglo-

the

matter had been eventually resolved by diplomatic means was a

turning point in Anglo- xxxxxIn the Sudan, there was much to be done. Following the

final defeat of the Mahdist forces at the Battle of Umm Diwaykarat

in November 1899, work was begun on the administration of the

country. An Anglo-

xxxxxIn the Sudan, there was much to be done. Following the

final defeat of the Mahdist forces at the Battle of Umm Diwaykarat

in November 1899, work was begun on the administration of the

country. An Anglo-