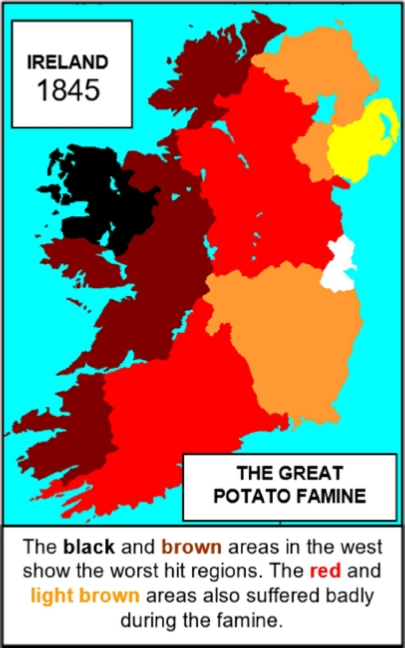

xxxxxThe Great Potato Famine struck Ireland in 1845 and brought untold misery and hardship over the next six years. It is estimated that nearly a million peasants, deprived of their staple and only crop, died of starvation and disease, and a greater number left Ireland to seek a better life in North America. Caused by a blight which rotted the potato in the ground, the famine was particularly harsh in the west, notably in Connaught and Munster. The fact that millions of peasants were forced to depend on one crop was largely due to the unsound and neglected condition of Irish agriculture at this time. The vast majority of farmers owned tiny smallholdings which gave no scope to diversify, and no chance to produce cash crops. In addition, rents were constantly being increased by extortionate land agents. The government of Robert Peel provided some money for the purchase of grain from North America, and his Repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 aimed to bring in cheaper food from abroad. The next administration introduced soup kitchens and work schemes, but such measures were not sufficient to cope with the extent of the crisis. Soon the workhouses were overcrowded with the sick, the starving, and the dying. Blame for the lack of provision was levelled at the British and, not surprisingly, within a few years revolutionary societies, such as the Republican Brotherhood and the Fenian Movement in the United States were established, bent on home rule for the Irish. This growing unrest was to lead to an uprising in 1867 (Vb), and the beginning of the Home Rule Association. The “Irish Question” was about to re-

THE GREAT POTATO FAMINE IN IRELAND

1845 -

Acknowledgements

Map (Ireland): by courtesy of www.irelandstory.com. Famine: engraving by the Cork artist James Mahoney (1810-

xxxxxThe Great Potato Famine, which struck Ireland in 1845 and continued for well over six years, brought untold suffering, misery and hardship to the people of the island. There had been a number of famines in the past, but none of such duration and severity. It is estimated that nearly a million people died of malnutrition, killed by diseases such as dysentery, cholera and scurvy. And to escape the famine and its consequences, an even larger number -

xxxxxThe Great Potato Famine, which struck Ireland in 1845 and continued for well over six years, brought untold suffering, misery and hardship to the people of the island. There had been a number of famines in the past, but none of such duration and severity. It is estimated that nearly a million people died of malnutrition, killed by diseases such as dysentery, cholera and scurvy. And to escape the famine and its consequences, an even larger number -

xxxxxThe cause of the catastrophe was a parasitic fungus known as phytophthora infestans or simply blight. Transmitted to Ireland by diseased potatoes or contaminated fertiliser, it killed off the potato crop in September 1845, re-

xxxxxThe fact that the Irish poor were so desperately dependent upon one crop -

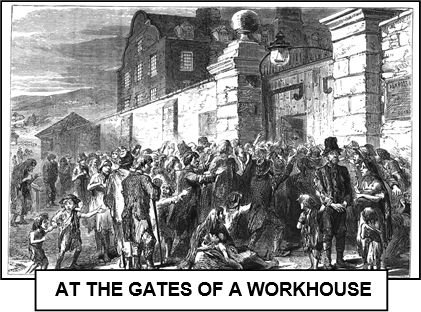

xxxxxThe areas worst hit by the famine were in the west, notably Connaught and Munster. As the population starved so the disease spread, the death toll mounted, and mass graves were dug across the land. Not all the dead were buried, however. Countless bodies of men, women and children were left to decay by the wayside, adding to the spread of disease. And such tragic, horrifying scenes were to be seen also in the workhouses and almshouses, where the overcrowded conditions and the lack of proper sanitation -

xxxxxThe areas worst hit by the famine were in the west, notably Connaught and Munster. As the population starved so the disease spread, the death toll mounted, and mass graves were dug across the land. Not all the dead were buried, however. Countless bodies of men, women and children were left to decay by the wayside, adding to the spread of disease. And such tragic, horrifying scenes were to be seen also in the workhouses and almshouses, where the overcrowded conditions and the lack of proper sanitation -

xxxxxThe scale of this disaster and the need for urgent action was not fully realised by the government at Westminster, remote as it was from the affairs of Ireland. By the time the extent of the crisis was realised it was virtually too late to avert a catastrophic train of events. In 1845 Robert Peel’s Tory administration did provide a grant of £105,000 to buy corn from the United States, and it also attempted to improve matters by the Repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 (thereby allowing the import of cheaper food from abroad), but such measures -

xxxxxAnd when the next government, that of John Russell, insisted that local landowners should make the necessary provision -

xxxxxIn 1848 the Whig government again turned to legislation, this time to restrict the current amount of poor relief. The “quarter-

xxxxxIn 1848 the Whig government again turned to legislation, this time to restrict the current amount of poor relief. The “quarter-

xxxxxThough the British government did take measures to alleviate the suffering of the Irish people, their efforts proved too little and too late in the face of such an appalling disaster. As a result, resentment against the union with Britain -

xxxxxIncidentally, the plight of those who emigrated during the famine is not always given the coverage it deserves. The “coffin ships” that crossed the Atlantic were crammed full of starving and diseased people, many of whom died during the voyage. An observer wrote: ‘‘Hundreds of poor people, men, women and children of all ages, were huddled together without light, without air, wallowing in filth and breathing a fetid atmosphere, sick in body, dispirited in heart”. ……

xxxxx…… Queen Victoria, we are told, was much moved by the suffering of the Irish people, and gave generously from her own purse. There were those, however, who complained that she and Prince Albert were more concerned with the building of Osborne House, their new, palatial home on the Isle of Wight, than with the tragedy unfolding in Ireland. ……

xxxxx…… The Irish-

xxxxx…… In 1995, one hundred and fifty years after the outbreak of the Great Potato Famine, the British prime minister made a public apology to the Irish people for the failure of the then British government to deal adequately with the tragic situation.

xxxxxThe Repeal of the Corn Laws was achieved by prime minister Robert Peel, a statesman already well known for his establishment of the first organised police force in 1829 (G4), and his controversial Catholic Emancipation Act of the same year. In 1845 he gained the support of the Whigs and a sufficient number of his own party (thanks largely to the influence of the Duke of Wellington) to put an end to this piece of protective legislation. A wartime tax on imported grain had been introduced in 1791 in order keep up grain prices at home, but in 1815 the landed gentry, the predominant body in Parliament, had passed a new Corn Law in order to keep the price of British grain artificially high, thus protecting their own commercial interests. Opposition to this partisan legislation gained much ground over the years, coming mainly from manufacturers and others who believed in the merits of free trade. In 1842 Peel himself, going against the wishes of his own Tory party, drastically reduced the extent of the protective duties contained in the Act. Then three years later the failure of the potato crop in Ireland convinced him that cheaper imports of grain were necessary to relieve the distress. It was for this reason that amid savage parliamentary debates he pushed through the repeal of the Corn Laws, reaping the wrath of his fellow Tories in the process (including the eloquent, up-

xxxxxThexmost powerful opposition to the restrictive measures of the Corn Laws, and one which exerted a great influence upon prime minister Peel, came from the Anti-

xxxxxThexmost powerful opposition to the restrictive measures of the Corn Laws, and one which exerted a great influence upon prime minister Peel, came from the Anti-

xxxxxIncidentally, as we have seen, the English economist David Ricardo, whose major work, Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, was published in 1817 (G3c), produced his Essay on the Influence of a Low Price of Corn on the Profits of Stock two years earlier. In this he put forward a strong case against imposing high tariffs on grain imports, arguing that whilst they tended to increase the rents of the landed gentry, they reduced the profits of the manufacturers, thereby depressing the nation’s industrial potential. ……

xxxxx…… As we shall see, the parliamentary orator John Bright was later to gain a national reputation for his vehement opposition to the Crimean War, its conduct and its peace settlement of 1856.

Including:

The Repeal of

the Corn Laws

Va-