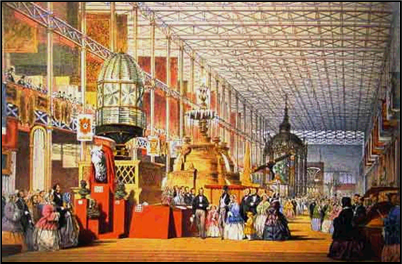

xxxxxThe Great Exhibition, staged in Hyde Park, London, during the summer of 1851, was held to display the “industries of all nations”. Exhibits came from all over the world. Particularly impressive was the industrial section, where model steam engines and locomotives were on view, together with recent innovations like the steam hammer, made by James Nasmyth, the new Bessemer process of making steel, and the precision-made tools required for mass production. In addition, the exhibition had on display thousands of everyday items, ranging from pottery, fabrics, furniture and photographic materials to musical instruments, sewing machines and kitchen appliances. All were housed in the “Crystal Palace”, a giant glasshouse, held in place by a vast cast-iron structure. Made to the design of the architect Joseph Paxton, it was over 45ft wide, nearly 2,000 ft. long, and covered an area of 196 acres. The exhibition gave ample proof that Britain had become the “workshop of the world”, but it was also evident that other countries, notably the United States, were fast catching up as industrial nations. The idea of holding such an exhibition was the brainchild of the design enthusiast Henry Cole, but the project was strongly supported and ably organised by Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert. The event, attended by over six million people, was a huge success, and the profits made from it enabled the founding of a number of London institutions, including Imperial College and the world-famous Victoria and Albert Museum.

THE GREAT EXHIBITION OF 1851 (Va)

xxxxx“The Great Exhibition of the Industries of All Nations”, as the Queen’s Consort, Prince Albert, named it, was held in Hyde Park, London, in the summer of 1851. It was a resounding success. Over six million people attended, many from Europe, and the vast profits made from it enabled the founding of several institutions in London, including Imperial College and the world-famous Victoria and Albert Museum.

xxxxx“The Great Exhibition of the Industries of All Nations”, as the Queen’s Consort, Prince Albert, named it, was held in Hyde Park, London, in the summer of 1851. It was a resounding success. Over six million people attended, many from Europe, and the vast profits made from it enabled the founding of several institutions in London, including Imperial College and the world-famous Victoria and Albert Museum.

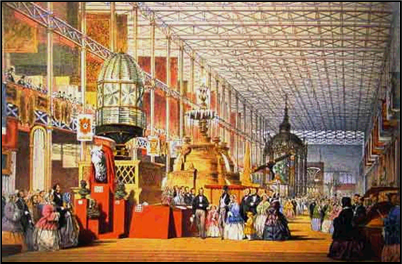

xxxxxWhilst the exhibition was open to all, the host country clearly had the advantage. Over half the 100,000 exhibits were from Britain and its Empire, including India, Australia and New Zealand. Most impressive was the industrial section. There, the working models of steam engines and the multitude of industrial uses to which they were being put, testified to the rapid advance of the Industrial Revolution in Britain. Alsoxon show in the Machinery Court were a selection of locomotives, the steam hammer made by James Nasmyth in 1840, the revolutionary Bessemer process of making steel - yet to be patented - and the new screw gauges introduced by the English engineer Joseph Whitworth (1803-1887), thread sizes which had been adopted by Woolwich Arsenal in 1841. These, together with a display of his drills, lathes and saws (precision-made tools to enable mass production), clearly showed Britain’s technological superiority and proved without doubt that Britain was, indeed, the “workshop of the world”.

xxxxxHowever, times were changing. Also on view from the United States was the large reaper designed by the inventor Cyrus Hall McCormick, the colt revolver, and a selection of rifles made up of interchangeable parts. And the German industrialist Alfred Krupp - later to become famous for his manufacture of war armaments - sent a steel casting weighing over two tons, an impressive achievement for that time. These two countries in particular were on their way to challenging Britain’s  supremacy.

supremacy.

xxxxxBut given that there were close on 14,000 exhibitors, the exhibition was by no means confined to achievements in the metal industry. On display was a vast selection of everyday articles from all over the world, ranging from furniture, pottery, and printed fabrics to photographic equipment, musical instruments, and kitchen appliances. Amongxtheir 560 items, for example, the Americans sent over chewing tobacco (gum was to come later!), false teeth, artificial legs, the domestic sewing machine invented by Isaac Singer, and india-rubber goods manufactured by Charles Goodyear (1800-1860). Andxpure art had its place. The English artist and sculptor Edwin Landseer (1802-1873), renowned for his paintings of animals and highly regarded by Queen Victoria, gained international fame for his Monarch of the Glen, completed earlier that year.

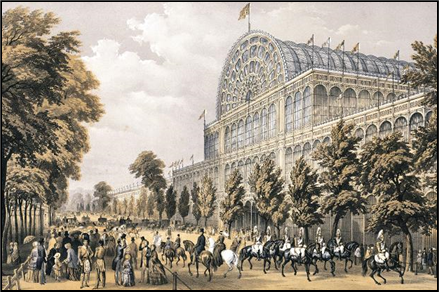

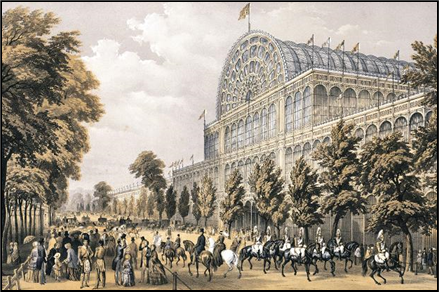

xxxxxBut more breathtaking than the displays themselves was the aptly named Crystal Palace, the building in which they were housed. Made up of an immense structure of some 300,000 panes of glass, each encased within a vast skeleton of cast-iron frames, it was over 450 ft. wide, nearly 2,000 ft. long, and spanned an area of some 200 acres. Constructed in Hyde Park, and tall enough to accommodate some of the park’s largest elm trees, it was a stunning piece of avant-garde architecture. Conceived by the landscape artist and architect Joseph Paxton (1803-1865) - a larger version as he saw it of the Great Conservatory he had built at Chatsworth Estate in Derbyshire! - it was chosen out of 233 designs submitted for consideration. It was in itself an extraordinary monument to engineering skill, and was at least one hundred years ahead of its time. Not surprisingly, Paxton - described in the Queen’s diary as “once a common gardener’s boy” - was knighted later in the year and given £5,000.

xxxxxBut more breathtaking than the displays themselves was the aptly named Crystal Palace, the building in which they were housed. Made up of an immense structure of some 300,000 panes of glass, each encased within a vast skeleton of cast-iron frames, it was over 450 ft. wide, nearly 2,000 ft. long, and spanned an area of some 200 acres. Constructed in Hyde Park, and tall enough to accommodate some of the park’s largest elm trees, it was a stunning piece of avant-garde architecture. Conceived by the landscape artist and architect Joseph Paxton (1803-1865) - a larger version as he saw it of the Great Conservatory he had built at Chatsworth Estate in Derbyshire! - it was chosen out of 233 designs submitted for consideration. It was in itself an extraordinary monument to engineering skill, and was at least one hundred years ahead of its time. Not surprisingly, Paxton - described in the Queen’s diary as “once a common gardener’s boy” - was knighted later in the year and given £5,000.

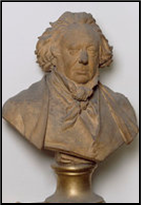

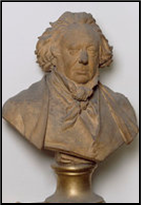

xxxxxIn the eyes of Queen Victoria, who opened the Exhibition on the 1st of May, the event confirmed her husband’s genius. She wrote at the time: “I do feel proud at the thought of what my beloved Albert’s great mind has conceived.” However, whilst Prince Albert did indeed play a highly significant role at all stages of the work involved, the idea of the exhibition was the brainchild of the little known design enthusiast Henry Cole (1808-1882) (illustrated). He was anxious to improve the design of everyday articles and, via his editorship of the Journal of Design, he had for long urged artists to apply their talents to the improvement of items such as pottery and furniture. These could then be manufactured in bulk and made available to the general public. What was required, he concluded, was an exhibition to promote and encourage such work. In 1846, as a member of the Society of Arts, he led a delegation to Prince Albert, seeking his support. Once given his enthusiastic backing and substantial influence, the planning got under way. At first, the inevitable objections were raised, but when the government learnt that the event was to be self-financing, it was seen as a means of highlighting the triumph of the Victorian Age, and enthusiasm for the project quickly gained momentum.

xxxxxIn the eyes of Queen Victoria, who opened the Exhibition on the 1st of May, the event confirmed her husband’s genius. She wrote at the time: “I do feel proud at the thought of what my beloved Albert’s great mind has conceived.” However, whilst Prince Albert did indeed play a highly significant role at all stages of the work involved, the idea of the exhibition was the brainchild of the little known design enthusiast Henry Cole (1808-1882) (illustrated). He was anxious to improve the design of everyday articles and, via his editorship of the Journal of Design, he had for long urged artists to apply their talents to the improvement of items such as pottery and furniture. These could then be manufactured in bulk and made available to the general public. What was required, he concluded, was an exhibition to promote and encourage such work. In 1846, as a member of the Society of Arts, he led a delegation to Prince Albert, seeking his support. Once given his enthusiastic backing and substantial influence, the planning got under way. At first, the inevitable objections were raised, but when the government learnt that the event was to be self-financing, it was seen as a means of highlighting the triumph of the Victorian Age, and enthusiasm for the project quickly gained momentum.

xxxxxThe Great Exhibition of 1851 certainly testified to Britain’s industrial supremacy, but, save for its building of steamships, its advance would be less spectacular from now on. Its industry would remain resourceful and creative, but during the remainder of the century, other countries, and particularly the United States, would speed up their economic growth, and begin to reduce Britain’s head start. Furthermore, the exceptional progress made by Britain, evident in many fields of endeavour, had been largely achieved at the expense of the working classes, the vast majority of whom lived in over-crowded slums and laboured long for little reward. The social evils so graphically described by the novelist Charles Dickens were by no means confined to his London. Such deprivation - the darker side of Victorian England - had yet to be addressed in earnest.

xxxxxIncidentally, after the closure of the exhibition, Henry Cole, who had served with distinction in the Public Record Office earlier in his career, played a prominent part in the founding of the Science Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington. Later he served for many years as director of both establishments, and the Henry Cole Wing of the V & A Museum is named after him. He also helped to found the Royal Albert Hall and the Royal College of Music. ……

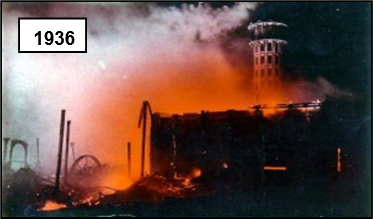

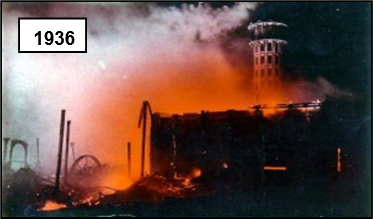

xxxxx…… Because of its unique construction, consisting of prefabricated sections bolted together, when the exhibition was over, the Crystal Palace was dismantled and re-erected in Penge Park at Sydenham, South London. Queen Victoria opened it for a second time in 1854, and it was then used for a variety of events, including music concerts, art exhibitions, dog and flower shows, and spectacular firework displays. A noted feature was the number of restaurants, serving meals to suit every pocket. It served as a training establishment in the First World War, but then, during a November night in 1936, it was destroyed by fire (illustrated). One tower was left standing, but this was pulled down during the Second World War to prevent it being used as a marker for German bombers attacking London. ……

xxxxx…… Because of its unique construction, consisting of prefabricated sections bolted together, when the exhibition was over, the Crystal Palace was dismantled and re-erected in Penge Park at Sydenham, South London. Queen Victoria opened it for a second time in 1854, and it was then used for a variety of events, including music concerts, art exhibitions, dog and flower shows, and spectacular firework displays. A noted feature was the number of restaurants, serving meals to suit every pocket. It served as a training establishment in the First World War, but then, during a November night in 1936, it was destroyed by fire (illustrated). One tower was left standing, but this was pulled down during the Second World War to prevent it being used as a marker for German bombers attacking London. ……

xxxxx…… The success of the London exhibition inspired others on the continent and across the Atlantic. Over the next few years alone, there were international exhibitions in New York and Dublin in 1853, Melbourne and Munich in 1854, and Paris in 1855. Another London exhibition, held in 1862 was less successful, however, marred by the death of Prince Albert the previous year. These and later exhibitions were often referred to as “world fairs”, a term used by the English novelist William Makepeace Thackeray in a poem he wrote about the London event in 1851. ……

xxxxx…… The Englishman Thomas Cook (1808-1892), a Baptist from Derbyshire, organised the visit of about 200,000 people to the Great Exhibition. Recognised today as the first tour operator in history, he began by arranging an excursion to a temperance meeting at Loughborough in 1841 - a package deal which included lunch - and organised his first all-inclusive tour to the continent in 1855. By the 1870s he was providing a “Cook’s Tour” around the world. ……

xxxxx...... But whilst the Exhibition can be considered a great success, concern was voiced about the paucity of British industrial design. Many argued, like the art critic John Ruskin, that machine produced goods, made in vast numbers, were identical in shape and form, and lacked the inspiration and unique style of individual craftsmanship. Such views, as we shall see, brought about the revival of the Pre-Raphaelite movement in the 1860s, inspired by the English painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and led by the talented art designer William Morris.

Va-1837-1861-Va-1837-1861-Va-1837-1861-Va-1837-1861-Va-1837-1861-Va-1837-1861-Va

Acknowledgements

Exhibition: artist unknown, contained in Dickinsons’ Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition, published 1854 – Science and Society Picture Library, Science Museum, London. Monarch: by the English painter Sir Edward Landseer (1802-1873), 1851 – National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh. Crystal Palace: coloured lithograph based on a painting by the English artist Philip Brannan (1817-1890) – Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Cole: terracotta bust by the British sculptor Joseph Edgar Boehm (1834-1890), 1875 – Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Fire: souvenir postcard to mark the event, photographer unknown. Albert: by the Scottish artist John Phillip (1817-1867) – Hull Guildhall, Yorkshire, England. Family: by the German painter Franz Xaver Winterhalter (1805-1873), 1846 – Royal Collection, UK. Osborne: drawn by the English artist William Henry Bartlett (1809-1854), and engraved by the English artist John Cousen (1804-1880), c1860. Memorial: date and artist unknown. Hall: date and artist unknown.

xxxxxPrince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (1819-1861) married his cousin, Queen Victoria, in 1840. It was a highly successful marriage and produced nine children. As Consort to the Queen, he became her chief advisor, particularly in matters of state, and she came to act upon his advice. And by this role he exercised a great deal of influence in both home and international affairs, though, like Victoria, he did not always remain neutral in matters of party politics. As a foreigner he was never very popular with the British people, but he eventually won their respect by his support for all things British, his concern for social progress, and the active encouragement he gave to the development of the arts, sciences and industry. Above all, he played a major role in the planning of the Great Exhibition of 1851, a symbol of national pride. A man who delighted to be with his family, and enjoyed the simple life, he helped to improve the standing of the royal family, and set the moral tone of the Victorian era. A workaholic, he succumbed to typhoid fever in 1861 and died at Windsor, aged 42. Victoria was heartbroken and never fully recovered from his death.

xxxxxPrince Albert (1819-61) - Albert Francis Charles Augustus Emmanuel of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, to give him his full name - married Queen Victoria, his cousin, in 1840, the wedding taking place in the Chapel Royal, St. James’ Palace, London. It appears that she proposed to him. Despite their diverse temperaments, it was a highly successful and happy marriage, and they had nine children by 1857. In the opening years of her reign, Victoria had tended to be impulsive and stubborn, but she had a deep affection for Albert and he thereby proved a restraining influence upon her. And, as Consort to the Queen, he also became her confidante and chief advisor, particularly in matters of state. She came to respect his opinions and to act on his advice. And by this role, sensitively managed for the most part, he exercised a deal of influence in both home and international affairs.

xxxxxPrince Albert (1819-61) - Albert Francis Charles Augustus Emmanuel of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, to give him his full name - married Queen Victoria, his cousin, in 1840, the wedding taking place in the Chapel Royal, St. James’ Palace, London. It appears that she proposed to him. Despite their diverse temperaments, it was a highly successful and happy marriage, and they had nine children by 1857. In the opening years of her reign, Victoria had tended to be impulsive and stubborn, but she had a deep affection for Albert and he thereby proved a restraining influence upon her. And, as Consort to the Queen, he also became her confidante and chief advisor, particularly in matters of state. She came to respect his opinions and to act on his advice. And by this role, sensitively managed for the most part, he exercised a deal of influence in both home and international affairs.

xxxxxIn the matter of party politics, he successfully encouraged Victoria to take a more neutral stand, in keeping with a constitutional monarchy (she had invited only a few Tories to her wedding!), but he did not always practise what he preached. He didn’t get on with Lord Palmerston and his bully-boy tactics, and he openly gave his support to the social reforms proposed by Sir Robert Peel. Nevertheless, during disputes with Prussia and the United States (the so-called Trent Affair of 1861) his plea for a moderate approach was heeded and led to a peaceful conclusion.

xxxxxAs a foreigner with a somewhat reserved disposition, he was never very popular with the British aristocracy, and was viewed with some suspicion by the general public - especially during the Crimean War - but as the years passed he won their respect by his genuine support for all things British, his real concern for social progress, and his active encouragement in the development of the country’s arts, sciences and industry. Indeed, his contribution to the success of the Great Exhibition - the highlight of their reign together - was quite phenomenal, and did much to make this international affair the success it proved to be. It became, in fact, a symbol of a vibrant Victorian Age, and greatly served to bolster national pride and confidence. And another but less well-known achievement was his complete overhaul of the running of the Royal Household, a long overdue reform which saved the nation some £25,000 a year.

xxxxxAs a foreigner with a somewhat reserved disposition, he was never very popular with the British aristocracy, and was viewed with some suspicion by the general public - especially during the Crimean War - but as the years passed he won their respect by his genuine support for all things British, his real concern for social progress, and his active encouragement in the development of the country’s arts, sciences and industry. Indeed, his contribution to the success of the Great Exhibition - the highlight of their reign together - was quite phenomenal, and did much to make this international affair the success it proved to be. It became, in fact, a symbol of a vibrant Victorian Age, and greatly served to bolster national pride and confidence. And another but less well-known achievement was his complete overhaul of the running of the Royal Household, a long overdue reform which saved the nation some £25,000 a year.

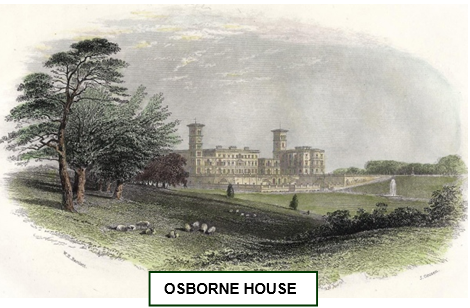

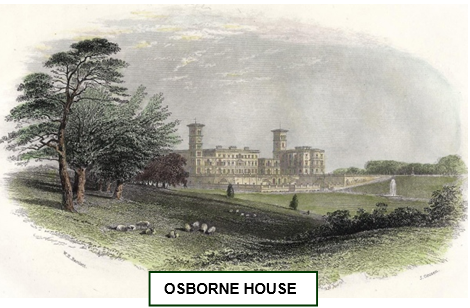

xxxxxBut whilst he possessed a dominant personality, he was, by nature, a simple man who loved to be with his family, enjoyed countryside pursuits, and found delight in music, being quite an accomplished  musician himself. To get away from London when possible, they bought Balmoral Castle in Scotland, and had Osborne House built on the Isle of Wight, designed in Italian style by Albert himself. His happy marriage, during which he remained ever faithful to his wife - in marked contrast to previous royal males! - helped to improve the standing of the monarchy, and set the moral tone and aura of respectability for which the Victorian era is remembered - though not always with justification! The Duke of Wellington described him as “extremely strait-laced and a great stickler for morality”.

musician himself. To get away from London when possible, they bought Balmoral Castle in Scotland, and had Osborne House built on the Isle of Wight, designed in Italian style by Albert himself. His happy marriage, during which he remained ever faithful to his wife - in marked contrast to previous royal males! - helped to improve the standing of the monarchy, and set the moral tone and aura of respectability for which the Victorian era is remembered - though not always with justification! The Duke of Wellington described him as “extremely strait-laced and a great stickler for morality”.

xxxxxAlbert entered wholeheartedly into all that he did - he was not a man to do things by halves - and this weakened his resistance to illness. It was while planning another trade fair, that of the South Kensington Exhibition of 1862, that, overburdened with work, he caught typhoid fever and failed to recover. He died at Windsor at the young age of 42, and was buried in the mausoleum at Frogmore, nearby. Victoria was heartbroken, and his tragic death was a blow from which she never fully recovered. She went into seclusion for a number of years, and remained in mourning for him for the rest of her life. From then on, every night his clothes were laid out on his bed, and every morning fresh water was put in his washbasin.

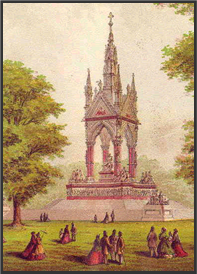

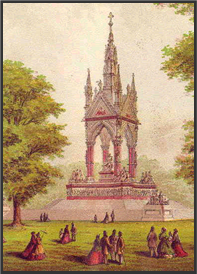

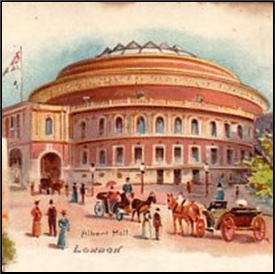

xxxxxIncidentally, afterxAlbert’s death Victoria had monuments to him built all over the country. Particularly well known are the Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens, London, (illustrated left), a work in Gothic Revival style by the English architect Gilbert Scott (1811-1878), and the Royal Albert Hall, built opposite (illustrated right). Both were completed in 1872. During his career Scott built or renovated a large number of churches, cathedrals and workhouses.x……

xxxxxIncidentally, afterxAlbert’s death Victoria had monuments to him built all over the country. Particularly well known are the Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens, London, (illustrated left), a work in Gothic Revival style by the English architect Gilbert Scott (1811-1878), and the Royal Albert Hall, built opposite (illustrated right). Both were completed in 1872. During his career Scott built or renovated a large number of churches, cathedrals and workhouses.x……

xxxxx…… Prince Albert introduced the Christmas tree from his homeland Germany. It soon became an essential feature of the festive season, along with Christmas cards. The Victorian tree was lit by candles, decorated with sweets and fancy cakes, and festooned with ribbon and paper chains. ……

xxxxx…… It is said that Albert’s last words were: “I have had wealth, rank and power, but if these things were all I had, how wretched I should be.” That is a measure of the man.

Including:

The Crystal Palace,

Henry Cole, and

Prince Albert

xxxxx“The Great Exhibition of the Industries of All Nations”, as the Queen’s Consort, Prince Albert, named it, was held in Hyde Park, London, in the summer of 1851. It was a resounding success. Over six million people attended, many from Europe, and the vast profits made from it enabled the founding of several institutions in London, including Imperial College and the world-

xxxxx“The Great Exhibition of the Industries of All Nations”, as the Queen’s Consort, Prince Albert, named it, was held in Hyde Park, London, in the summer of 1851. It was a resounding success. Over six million people attended, many from Europe, and the vast profits made from it enabled the founding of several institutions in London, including Imperial College and the world- supremacy.

supremacy.  xxxxxBut more breathtaking than the displays themselves was the aptly named Crystal Palace, the building in which they were housed. Made up of an immense structure of some 300,000 panes of glass, each encased within a vast skeleton of cast-

xxxxxBut more breathtaking than the displays themselves was the aptly named Crystal Palace, the building in which they were housed. Made up of an immense structure of some 300,000 panes of glass, each encased within a vast skeleton of cast- xxxxxIn the eyes of Queen Victoria, who opened the Exhibition on the 1st of May, the event confirmed her husband’s genius. She wrote at the time: “I do feel proud at the thought of what my beloved Albert’s great mind has conceived.” However, whilst Prince Albert did indeed play a highly significant role at all stages of the work involved, the idea of the exhibition was the brainchild of the little known design enthusiast Henry Cole (1808-

xxxxxIn the eyes of Queen Victoria, who opened the Exhibition on the 1st of May, the event confirmed her husband’s genius. She wrote at the time: “I do feel proud at the thought of what my beloved Albert’s great mind has conceived.” However, whilst Prince Albert did indeed play a highly significant role at all stages of the work involved, the idea of the exhibition was the brainchild of the little known design enthusiast Henry Cole (1808- xxxxx…… Because of its unique construction, consisting of prefabricated sections bolted together, when the exhibition was over, the Crystal Palace was dismantled and re-

xxxxx…… Because of its unique construction, consisting of prefabricated sections bolted together, when the exhibition was over, the Crystal Palace was dismantled and re- xxxxxPrince Albert (1819-

xxxxxPrince Albert (1819- xxxxxAs a foreigner with a somewhat reserved disposition, he was never very popular with the British aristocracy, and was viewed with some suspicion by the general public -

xxxxxAs a foreigner with a somewhat reserved disposition, he was never very popular with the British aristocracy, and was viewed with some suspicion by the general public - musician himself. To get away from London when possible, they bought Balmoral Castle in Scotland, and had Osborne House built on the Isle of Wight, designed in Italian style by Albert himself. His happy marriage, during which he remained ever faithful to his wife -

musician himself. To get away from London when possible, they bought Balmoral Castle in Scotland, and had Osborne House built on the Isle of Wight, designed in Italian style by Albert himself. His happy marriage, during which he remained ever faithful to his wife -

xxxxxIncidentally, afterxAlbert’s death Victoria had monuments to him built all over the country. Particularly well known are the Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens, London, (illustrated left), a work in Gothic Revival style by the English architect Gilbert Scott (1811-

xxxxxIncidentally, afterxAlbert’s death Victoria had monuments to him built all over the country. Particularly well known are the Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens, London, (illustrated left), a work in Gothic Revival style by the English architect Gilbert Scott (1811-