THE ELGIN MARBLES 1802 -

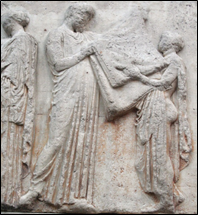

xxxxxAs we have seen, the ancient Greek temple called The Parthenon, a magnificent example of Doric architecture, was virtually destroyed when, following the Second Battle of Mohacs in 1687 (J2), the Venetians invaded Greece and bombarded the city of Athens. It was the remains of this building which attracted the Earl of Elgin when he became ambassador to the Ottoman Empire in 1799. Fearing that the Turks, then in charge of Athens, would break up the ruined temple for building material, he obtained their permission to take away some of the sculptures. Over the years 1802 to 1812 he shipped to England some 50 pieces, mainly from the frieze of the ancient temple. On his return to England in 1806 many, including the poet Lord Byron, accused him of theft and vandalism, but he published a paper to defend his actions, and a parliamentary enquiry vindicated him. In 1816 the British government bought the sculptures, by then known as the “Elgin Marbles”, and they have been displayed in the British Museum, London, ever since.

xxxxxIt was in 1802 that shipment began to England of a large collection of ancient Greek sculptures and architectural detail. Over the next ten years something like 50 pieces, packed in crates, were transported to England, and by 1812 all had arrived safely. One ship, HMS Mentor, did sink off the Greek island of Cythera in 1804, but its precious cargo was recovered. For the most part these large fragments were taken from the ruin that was once the Temple of Athena Parthenos (The Parthenon) and which, from its position on the Acropolis, had dominated the city of Athens for over 2,000 years.

xxxxxIt was in 1802 that shipment began to England of a large collection of ancient Greek sculptures and architectural detail. Over the next ten years something like 50 pieces, packed in crates, were transported to England, and by 1812 all had arrived safely. One ship, HMS Mentor, did sink off the Greek island of Cythera in 1804, but its precious cargo was recovered. For the most part these large fragments were taken from the ruin that was once the Temple of Athena Parthenos (The Parthenon) and which, from its position on the Acropolis, had dominated the city of Athens for over 2,000 years.

xxxxxAs we have seen, this magnificent example of Doric architecture from the 5th century BC was almost blown to pieces when, following the defeat of the Ottoman Turks at the Second Battle of Mohacs in 1687 (J2), the Venetians had invaded Greece and bombarded the city of Athens. When the Turks, who ruled over Greece at this time, re-

xxxxxThe transhipment of these ancient artworks was arranged by the then British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin (1766- secured permission not only to measure and sketch significant pieces of sculpture and architectural detail, but also “to take away any pieces of stone with old inscriptions or figures thereon”. Needless to say, he jumped at the chance.

secured permission not only to measure and sketch significant pieces of sculpture and architectural detail, but also “to take away any pieces of stone with old inscriptions or figures thereon”. Needless to say, he jumped at the chance.

xxxxxThe vast collection of treasures which he selected -

xxxxxElgin left for home in 1803, but he was detained in France for three years following the resumption of the Napoleonic Wars, and he did not reach England until 1806. The marbles were put on display the following year, and it was then that he found himself in the eye of a storm. There were many people, the poet Lord Byron among them, who roundly condemned him for his dishonesty and vandalism. Others accused him of theft, and some even questioned the value of his ill- Turks were totally indifferent to their fate a

Turks were totally indifferent to their fate a nd he genuinely feared that such priceless treasures would have been destroyed and lost for ever. Then the Parliamentary committee came out in his favour, and this tended to silence some of the criticism. However, the controversy rumbled on late into the 20th century, and to this day has not really gone away.

nd he genuinely feared that such priceless treasures would have been destroyed and lost for ever. Then the Parliamentary committee came out in his favour, and this tended to silence some of the criticism. However, the controversy rumbled on late into the 20th century, and to this day has not really gone away.

xxxxxEventually, in 1816, after much persuasion by Elgin, the British government -

xxxxxThe arrival of the Elgin Marbles in London, together with the publication of Antiquities of Athens, produced in four volumes by the English architects Nicholas Revett and James Stuart, served in particular to awaken an interest in the architectural heritage of Greece as opposed to Rome. A number of British architects, such as John Nash, were influenced by this “Greek Revival”, and the romantic poets were clearly inspired by all things Greek. Shown here -

Acknowledgements

Earl of Elgin: by the Swiss portrait painter Anton Graff (1736-

Including:

The Earl of Elgin

and

Antonio Canova

G3c-

xxxxxIncidentally, while Lord Byron lamented that great works of Greek antiquity had been “defac’d by British hands”, the poet John Keats wrote a sonnet to celebrate their arrival, and the German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe hailed their acquisition as “the beginning of a new age for Great Art”.

xxxxxThe Italian Antonio Canova (1757-

xxxxxOne of the sculptors who inspected the Elgin Marbles on behalf of the British government was the Italian master Antonio Canova (1757-

xxxxxOne of the sculptors who inspected the Elgin Marbles on behalf of the British government was the Italian master Antonio Canova (1757-

xxxxxCanova was born 1757 and, losing his parents at an early age, was brought up by his grandfather Pasino, a stonemason in Possagno, near Venice. He later studied at the Venice Academy and by the mid 1770s, having set up his own studio, had gained a wide reputation as a portraitist, receiving commissions from nobility in Venice, Rome and as far away as London. His early statutory, such as the highly realistic Daedalus and Icarus was in the baroque manner, but on visits to Rome in 1779 and 1780 he became caught up in the revival movement in Greek and Roman art. He mixed with the classical artists of the day, and went on to visit the ancient ruins then being uncovered at Pompeii and Herculaneum.

xxxxxIn 1781 he moved to Rome and, being of a congenial disposition, soon became a well-

xxxxxIn 1781 he moved to Rome and, being of a congenial disposition, soon became a well-

xxxxxSome of this work was done outside of Rome. In 1798, following the French invasion of the city, Canova worked for a while in Venice and then, in 1802 was invited to Paris by Napoleon. Here he became court sculptor, and over the next ten years produced a bust, an equestrian statue and, in 1811, two huge heroic nudes of the emperor in classical pose.

xxxxxAfter the fall of Napoleon, Canova was assigned the task of going to Paris and retrieving all the art treasures that the French emperor had taken from Italy. For his part in this work he was created the Marquess d’Ischia by the Pope. It was after this that he went to London to assess the value of the Elgin Marbles, and while there he was commissioned by the Prince Regent to produce a life-

xxxxxAfter the fall of Napoleon, Canova was assigned the task of going to Paris and retrieving all the art treasures that the French emperor had taken from Italy. For his part in this work he was created the Marquess d’Ischia by the Pope. It was after this that he went to London to assess the value of the Elgin Marbles, and while there he was commissioned by the Prince Regent to produce a life-

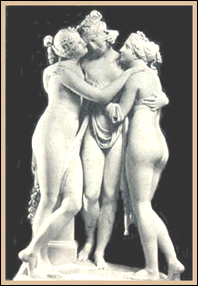

xxxxxIllustrated here are three of his well-

xxxxxCanova died in Venice in 1822 and was buried at Possagno in a temple he had designed in the form of the Pantheon in Rome. A much respected and admired man, his place as the leading exponent of neo-