THE EIGHTH CRUSADE 1270 (H3)

PLUS A SUMMARY OF THE CRUSADES AND THEIR RESULTS

Including:

Louis IX of France

xxxxxAs we have seen, in 1248 Louis IX of France was defeated and captured when he took the Seventh Crusade to Egypt. Undeterred, in 1270 he mustered the Eighth Crusade and led an attack upon Tunisia. This also met with disaster. Soon after arriving, he and his son died of disease, and the whole enterprise was abandoned. Prince Edward of England, arriving late, took his force on to the Holy Land but could do little. By that time nearly all the English enclaves had been attacked and destroyed by the Mamluk leader Baybars. Indeed, as we shall see, the fall of Acre twenty years later in 1291 (E1) virtually put an end to the crusading movement.

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Seventh Crusade of 1248, like the fifth, was directed against Egypt and proved an even greater disaster. Launched in response to the Muslim occupation of Jerusalem in 1244, it succeeded in taking Damietta, but the attack on Cairo ended in total defeat. The crusade’s leader, Louis IX of France, was captured together with much of his army, and a huge ransom had to be paid to gain the king's release.

xxxxxUndeterred, in 1270 Louis led another expedition, the Eighth Crusade, this time aimed at the Muslims in Tunisia. But his army was under-

xxxxxBy this time the Crusader states in Palestine and Syria had all but disappeared, overrun and devastated by a new Egyptian dynasty known as the Mamluks. Under one of their most able leaders, Sultan Baybars, -

xxxxxDespite his failures in the Seventh and Eighth Crusades, first in Egypt and then in Tunisia, Louis IX (1214-

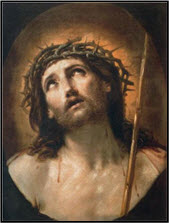

xxxxxIncidentally, in 1239 Louis bought from the Byzantine Empire, then on the verge of bankruptcy, two relics purported to be from Christ’s crucifixion -

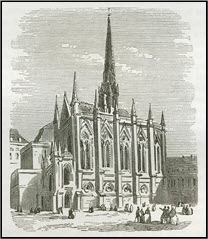

xxxxxIncidentally, in 1239 Louis bought from the Byzantine Empire, then on the verge of bankruptcy, two relics purported to be from Christ’s crucifixion - example of Gothic architecture, it contains two chapels in fact, a lower one for the king’s servants and a higher one for the royal family. Because of its three walls of stained glass windows, over 50 feet in height and dating from the 13th century, in bright weather the upper section is flooded with coloured light and has been likened to a jewel box. The building was damaged by fire in the 17th century, and ransacked during the French Revolution, but completely restored during the reign of Louis-

example of Gothic architecture, it contains two chapels in fact, a lower one for the king’s servants and a higher one for the royal family. Because of its three walls of stained glass windows, over 50 feet in height and dating from the 13th century, in bright weather the upper section is flooded with coloured light and has been likened to a jewel box. The building was damaged by fire in the 17th century, and ransacked during the French Revolution, but completely restored during the reign of Louis-

H3-

A SUMMARY OF THE CRUSADES

xxxxxAs you many recall, the First Crusade was called for in November 1095 and proved a resounding success. Deeply troubled by the advance of the Seljuk Turks in the Middle East and the loss of Syria and Palestine to the infidel, the Christian kingdoms of Western Europe amassed a large army and by July 1099 had recaptured the Holy City of Jerusalem and set up four Christian states in the area, the largest being the Kingdom of Jerusalem. This was the high-

xxxxxThe Second Crusade got off to a promising start in 1145, led by the French and German kings, but it ended in failure and humiliation. The German army was virtually annihilated on reaching Anatolia, and the French force, having suffered heavy loses on the way, failed to capture Damascus and decided to return home.

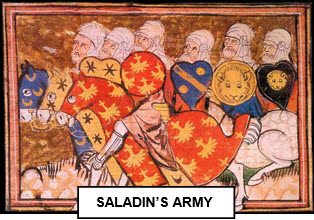

xxxxxBy the time of the Third Crusade in 1189, the Muslims had become united under the leadership of their able leader Saladin and were a force to be reckoned with. When Jerusalem fell to the Muslims in 1187 it was inevitable that the West would send a military expedition. On the face of it, this force was a powerful one, led by the kings of Germany, France and England, but what they had in strength they lacked in unity. The Germans went their own way and returned home when their king, Barbarossa, died in Anatolia. The French and English argued over strategy until Philip Augustus, more concerned with the defence of his own territories in Europe, took most of his army back to France. By negotiating a peace settlement with Saladin, Richard did manage to retain a Latin Kingdom in a slither of land along the Palestinian coast, but Jerusalem remained firmly in the hands of the Muslims.

xxxxxBy the time of the Third Crusade in 1189, the Muslims had become united under the leadership of their able leader Saladin and were a force to be reckoned with. When Jerusalem fell to the Muslims in 1187 it was inevitable that the West would send a military expedition. On the face of it, this force was a powerful one, led by the kings of Germany, France and England, but what they had in strength they lacked in unity. The Germans went their own way and returned home when their king, Barbarossa, died in Anatolia. The French and English argued over strategy until Philip Augustus, more concerned with the defence of his own territories in Europe, took most of his army back to France. By negotiating a peace settlement with Saladin, Richard did manage to retain a Latin Kingdom in a slither of land along the Palestinian coast, but Jerusalem remained firmly in the hands of the Muslims.

xxxxxThe Fourth Crusade was a crusade in name only. It started out with high hopes in 1202 but, becoming embroiled in Venetian politics, it ended up attacking and sacking Constantinople and replacing the Christian Byzantine Empire with a Latin Kingdom. This survived for less than sixty years and made no contribution to the cause of the Crusaders.

xxxxxIn 1208 a crusade was launched within Europe. Directed at the Albigensians (or Cathars), a religious sect in southern France which posed a threat to orthodox views, thousands of these heretics were killed and much damage was done to the local economy during a campaign which lasted for more than twenty years. Those who did survive eventually became victims of the Inquisition. And it was during this campaign that the tragic event known as the Children's Crusade was carried out.

xxxxxThe Fifth Crusade, beginning in 1217 and led by Andrew of Hungary, was directed towards Egypt. It was argued that if Cairo could be captured and then control secured over the Sinai peninsula, the Muslims to the north would be cut off from the support and -

xxxxxThe Fifth Crusade, beginning in 1217 and led by Andrew of Hungary, was directed towards Egypt. It was argued that if Cairo could be captured and then control secured over the Sinai peninsula, the Muslims to the north would be cut off from the support and -

xxxxxThe Sixth Crusade was really not a crusade at all, unless we see it as a “diplomatic” crusade. Emperor Frederick II of Germany led out an expedition in 1228 but, on arriving in Egypt, negotiated a agreement with the Sultan whereby the Christians not only regained possession of Jerusalem, but also the cities of Bethlehem and Nazareth. Indeed, Frederick was crowned king of Jerusalem the following year. The holy city was, in fact, recaptured by the Muslims in 1244, but it was nevertheless a diplomatic coup on the part of the German Emperor.

xxxxxAs we have seen above, the last two major crusades were led by Louis IX of France. The Seventh Crusade, launched against Egypt in 1249, was soundly defeated outside Cairo, and the Eighth, directed at Tunisia, was abandoned following the death of Louis in 1270.

Acknowledgements

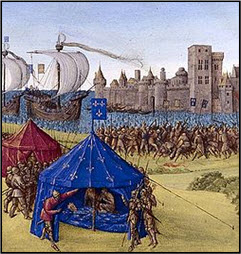

Eighth Crusade: from Les Grandes Chroniques de France, illuminated by the French painter Jean Fouquet, 15th Century – National Library of France, Paris. Ecce Homo: by the Italian painter Guido Reni (1575-

Acknowledgements

Saladin’s Army: from Histoire d’Outremer by Guillaume de Tyr (C1130-

H3-

THE RESULTS OF THE CRUSADES

xxxxxThere is always a danger of exaggerating the results of the Crusades, but, spread as they were over two centuries, they clearly had some important, wide-

xxxxxOne of their most enduring legacies was the boost they gave to trade, not only for the Italian cities, but also for the bustling ports and markets of the Middle East. Crusaders brought home a variety of spices, colourful textiles, and various items of hardware. These had been available earlier through other channels, of course, but never on so large a scale. The re were, too, the fiscal implications. The Italian banking system was given an enormous boost, and became more streamlined to meet the needs of these colossal undertakings, whilst Kings and Popes alike were obliged to introduce more efficient means of raising funds, including direct taxation. And the shipping industry also benefited from the increased demand within the Mediterranean.

re were, too, the fiscal implications. The Italian banking system was given an enormous boost, and became more streamlined to meet the needs of these colossal undertakings, whilst Kings and Popes alike were obliged to introduce more efficient means of raising funds, including direct taxation. And the shipping industry also benefited from the increased demand within the Mediterranean.

xxxxxThe military failure associated with all but one of these Crusades also had an effect. Not only did it undermine the authority of the Pope, but it clearly showed the disunity which existed within the Christian Church itself. National armies had often acted alone -

xxxxxSome joined the ranks of the Crusaders out of sheer greed, hoping to gain from the booty of war, whilst others were genuinely committed to the Christian cause, or saw their involvement as an expedient means of gaining salvation. There was, too, a large number of men who went in search of new horizons, and it was this spirit of adventure, awakened in the hearts of so many men at this time, which was later to play so prominent a part in the discovery of the New World.

xxxxxThere was, too, some spin-

H3-