xxxxxAs we have seen, it was in 1875 (Vb) that Ismail Pasha, the Khedive of Egypt, virtually made bankrupt by his sheer extravagance, was forced to sell his shares in the Suez Canal Company. They were snapped up by the then British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli, and this gave Britain a commanding interest in the running of this vital waterway, a valuable short-cut to the Far East. In 1876, to save Egypt from sliding into bankruptcy, the Commission for Public Debt was established, and the French and the British, working together - the “Dual Control” - took over the country’s financial affairs. State spending was controlled, and the following year, to reduce the Khedive’s authority and extravagance, Ismail Pasha was obliged to introduce a constitutional form of government. This political reform was quickly undermined, however, and behind the scenes he made plans to rid the country of international control. As a result, in June 1879, at the request of the British and French, the Sultan of Turkey deposed Ismail in favour of his son Tewfik.

xxxxxButxthis  virtual take-over of the country by two western powers stirred up opposition, particularly in the army, and a nationalist movement emerged led by a young Arab officer named Colonel Ahmed Urabi (1841-1911). Having been appointed undersecretary for war and then gaining a place in the cabinet, he began to agitate for the removal of all foreigners, gaining support not only from the military, but also from among the educated classes and the bulk of the peasantry. His cry “Egypt for the Egyptians” made him a national hero at the head of a national rebellion. Tewfik, lacking any real support, was powerless to stop this growing revolt. Eventually in 1882, following a military demonstration of defiance in Cairo which amounted to a mutiny, he called upon Britain and France to help him reassert his authority.

virtual take-over of the country by two western powers stirred up opposition, particularly in the army, and a nationalist movement emerged led by a young Arab officer named Colonel Ahmed Urabi (1841-1911). Having been appointed undersecretary for war and then gaining a place in the cabinet, he began to agitate for the removal of all foreigners, gaining support not only from the military, but also from among the educated classes and the bulk of the peasantry. His cry “Egypt for the Egyptians” made him a national hero at the head of a national rebellion. Tewfik, lacking any real support, was powerless to stop this growing revolt. Eventually in 1882, following a military demonstration of defiance in Cairo which amounted to a mutiny, he called upon Britain and France to help him reassert his authority.

xxxxxFearing that Urabi and his large following would bring instability and plunge the country further into debt, (both the British and the French had a considerable amount of investment in Egypt), and even pose a threat to the Suez Canal itself, both countries agreed to station fleets off the coast at Alexandria. But this show of strength, meant to intimidate the rebels, only made matters worse. In June, amid fears that an invasion was imminent, anti-European riots broke out in Alexandria in the course of which some 50 Europeans were killed. This was seen as the start of the so called “Urabi Revolt”. In fact, Urabi was not behind this uprising. Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that it was Tewfik who organised the troubles in order to hasten armed intervention and save his throne!

xxxxxAt this juncture, however, the Dual Control administration became clearly split as to what action should be taken. The British government considered that a military response was necessary to stabilize the country - and safeguard its own interests. On the other hand, the French government, no longer led by Jules Ferry - a prime minister who had been in favour of colonial expansion - decided against armed intervention. It was currently facing problems in Algeria and Tunisia, and it had no wish to take on another risky foreign adventure. At the same time, however, it had no desire to see Egypt fall into British hands. Atxits request, therefore, the Constantinople Conference was convened in June 1882. All those attending (save Britain, of course) - Russia, Austria, Germany, Italy and France - opposed any form of unilateral activity in Egypt. Britain fully agreed, providing that there was no extraordinary circumstance - a force majeur - which necessitated such intervention.

xxxxxThe following month - conveniently you might think - the British found themselves faced with such an “extraordinary circumstance”. Urabi began to update the coastal batteries at Alexandria, and this was construed as a threat to the British ships anchored off-shore. He was told to stop all repair work and, when he refused to do so, the British felt compelled to take action. In July 1882 their warships bombarded the shoreline to destroy the gun emplacements, and then a naval force was landed at the port - or what was left of it - to restore law and order. By that time the Egyptian army had withdrawn from the city. The Anglo-Egyptian War was under way. Alarmed at such events, the Constantinople Conference persuaded the Turkish government to send a military force to Egypt (then part of the Ottoman Empire) - with the clear intention of putting an end to British designs - but Anglo-Turkish negotiations concerning this intervention dragged on for so long that the war was over before such action could be taken!

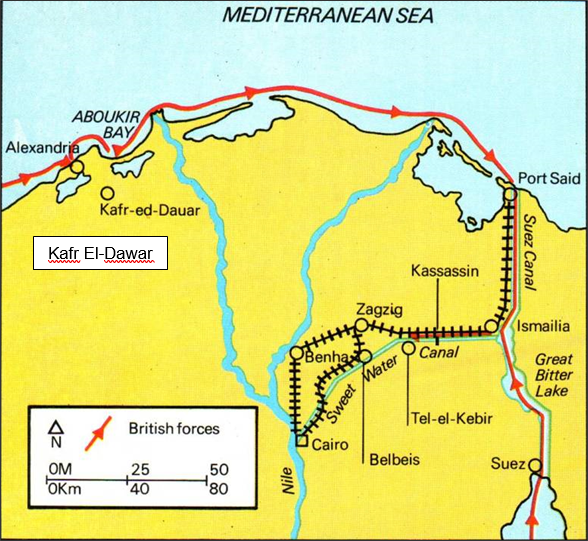

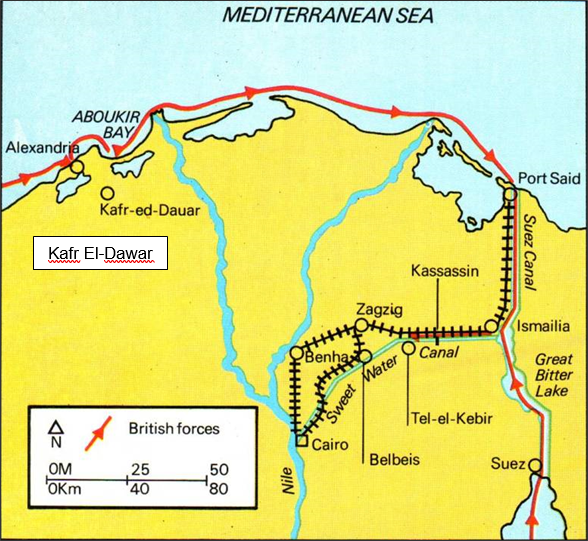

xxxxxGeneral Sir Garnet Wolseley was appointed the British commander, the soldier who, as we have seen, distinguished himself in the Third Anglo-Ashanti War nine years earlier. With over 24,000 troops at his disposal, drawn mainly from the garrisons in Cyprus, Malta and Gibraltar, he planned an attack on Cairo from the Suez Canal. However, towards the end of July, in order to mislead his enemy, he sent a sizeable force from Alexandria to march on the capital. Having reached the city of Kafr El-Dawar, however, a short distance inland, it was met by a large Egyptian force, led by Urabi. Well armed and occupying a strong defensive position, the Egyptians held the British at bay and, after five weeks, forced them to retire.

xxxxxIn the meantime, however, Wolseley, by means of eight warships and 17 transporters, carried the bulk of his army to Port Said and then through the Suez Canal to Ismailia, embarking on the 20th August. There, having been joined by an Anglo-Indian contingent of 7,000 men staged through Aden, he prepared for his attack on the capital. Earlier Urabi had intended to block the Suez Canal and close the fresh-water canal that joins the Nile with Ismailia, but having been convinced by Ferdinand de Lesseps, the canal’s chief engineer, that the British would not involve the Suez Canal Zone in the fighting, he did not do so. Had he taken these steps it might well have altered the course of the conflict or, at least, prolonged it.

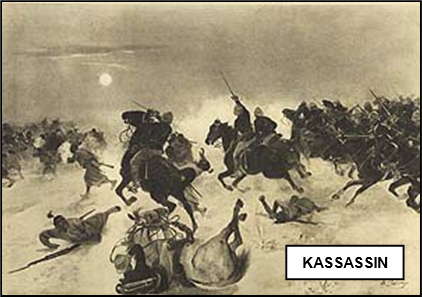

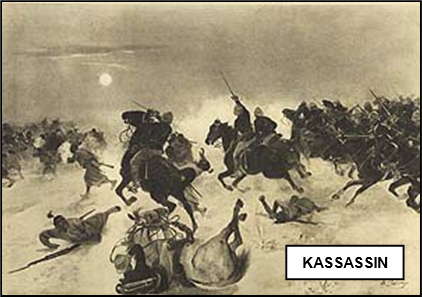

xxxxxHaving taken over the Canal’s installations and local garrisons, Wolseley sent an advance force of some 2,000 men to Kassassin, some 20 miles west of Ismailia. It was important to defend the lock there, situated on the Fresh Water Canal, to ensure an adequate supply of drinking water for the invasion force. As a consequence, over the next two weeks this garrison came under almost constant fire, and was attacked in force on two occasions. The first, at the end of August, was successfully repulsed in the early evening by a cavalry charge of the Household Cavalry - an attack which has gone down in popular history as taking place at midnight (illustrated) - and the second, launched just before the advance on Cairo in mid-September, pressed the British hard and was only driven off after the timely arrival of reinforcements.

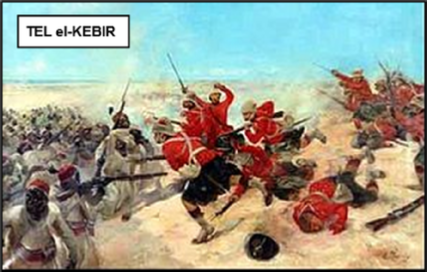

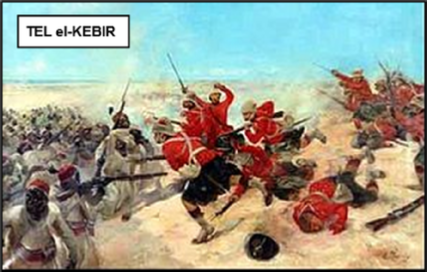

xxxxxForxthe assault on Cairo the British force - 17,500 men and 60 guns - was assembled at Kassassin and moved out on the 12th September. Because of the open desert to be crossed Wolseley had decided to march at night and surprise the enemy at first light. The Egyptians, about 38,000 strong and with a similar number of artillery pieces, had taken up their position at Tel el-Kebir, about eleven miles away. By way of defence they had laid out an impressive line of deep ditches and steep embankments, but many of their soldiers had little experience of the weapons at their disposal and, indeed, of war itself. By dawn on the 13th September 1882 the forward troops of the British force had reached to within 300 yards of their enemy’s lines, and it was only then that the Egyptians realised they were under attack. The element of surprise proved the decisive factor. A bayonet charge, followed by a cavalry charge quickly overwhelmed the “Urabists” and forced them to retreat with heavy losses, estimated at 2,000. The battle was over in less than an hour and this opened the way to Cairo. The capital was occupied the next day, and towards the end of the month the Khedive returned to Cairo. He was officially reinstated and a new ministry formed. Urabi was captured during the fighting. For his part in the revolt he was sentenced to death but, to avoid any backlash this might cause, his sentence was commuted to exile on the island of Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka), along with six other leading rebels.

by a cavalry charge quickly overwhelmed the “Urabists” and forced them to retreat with heavy losses, estimated at 2,000. The battle was over in less than an hour and this opened the way to Cairo. The capital was occupied the next day, and towards the end of the month the Khedive returned to Cairo. He was officially reinstated and a new ministry formed. Urabi was captured during the fighting. For his part in the revolt he was sentenced to death but, to avoid any backlash this might cause, his sentence was commuted to exile on the island of Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka), along with six other leading rebels.

xxxxxBritain’sxoccupation of Egypt was to last until 1954, and it gained French recognition in 1904 in return for the acknowledgement of French rights in Morocco. In the immediate wake of the war, the responsibility of restoring law and order fell to the high commissioner, Lord Dufferin, but it is Evelyn Baring (1841-1917) - later Lord Cromer -, consul general from 1883 to 1907, who is remembered today for the widespread practical reforms he introduced in bringing about the development of Egypt as a modern state.

xxxxxBut the government of Egypt - a formidable task in itself - was also to involve Britain in the affairs of the Sudan, Egypt’s dependent (and highly unstable) territory. In the first instance, as we shall see, this was to lead to the First Anglo-Sudan War, the siege of Khartoum, and the slaughter of General Charles Gordon and his garrison in January 1885.

xxxxxIncidentally, before Sir Garnet Wolseley left England to take up his command, he had decided on the plan to invade Egypt via the Suez Canal and had predicted that the decisive battle would take place near Tel el-Kebir, on or around the 12th September!

virtual take-

virtual take-

by a cavalry charge quickly overwhelmed the “Urabists” and forced them to retreat with heavy losses, estimated at 2,000. The battle was over in less than an hour and this opened the way to Cairo. The capital was occupied the next day, and towards the end of the month the Khedive returned to Cairo. He was officially reinstated and a new ministry formed. Urabi was captured during the fighting. For his part in the revolt he was sentenced to death but, to avoid any backlash this might cause, his sentence was commuted to exile on the island of Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka), along with six other leading rebels.

by a cavalry charge quickly overwhelmed the “Urabists” and forced them to retreat with heavy losses, estimated at 2,000. The battle was over in less than an hour and this opened the way to Cairo. The capital was occupied the next day, and towards the end of the month the Khedive returned to Cairo. He was officially reinstated and a new ministry formed. Urabi was captured during the fighting. For his part in the revolt he was sentenced to death but, to avoid any backlash this might cause, his sentence was commuted to exile on the island of Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka), along with six other leading rebels.