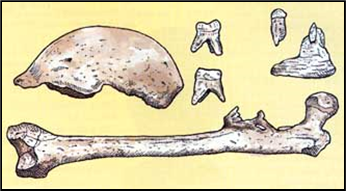

xxxxxIn 1892 the Dutch anatomist and geologist Eugène Dubois, searching for the “missing link” between ape and man in the evolutionary scale, discovered a skullcap, femur and some teeth while working on the island of Java in the East Indies. He claimed that this “Java Man” was in fact the missing link and, having published his findings in 1894, returned home the following year to conduct a lecture tour across Western Europe. Scientists who supported the evolutionary theory applauded his work, but many questioned his interpretation. Doubt was cast as to whether the skullcap and femur came from the same individual, some thought the skull was from a giant gibbon, whilst others considered that the creature was an early human. Such was the controversy this aroused that in 1900 Dubois hid the fossils away and did not show them again until the early 1930s. He continued to insist that the Java man was the missing link -

EUGÈNE DUBOIS 1858 -

Acknowledgements

Dubois: detail, date and artist unknown. Java Man: impression of the “Upright Ape Man”, artist unknown. Map (Jubaland): from www.ilcornodafrica.it/es-

xxxxxIt was in early 1890s, while working in Java, Indonesia, that a young Dutch anatomist and geologist named Eugène Dubois discovered a thick-

xxxxxIt was in early 1890s, while working in Java, Indonesia, that a young Dutch anatomist and geologist named Eugène Dubois discovered a thick-

xxxxxDubois was born in Eijsden. As a child he showed a keen interest in natural history, and he was encouraged in this by his father, a local pharmacist. He studied medicine at the University of Amsterdam and after graduating as a doctor, became a lecturer in anatomy there in 1886. The following year, however, having become increasingly interested in human evolution, he gave up his job to do some active research. Inspired by the German zoologist Ernst Haeckel, who argued that there was a need to find the “missing link” in the development of the ape to the human, and convinced that this was to be found in a tropical climate, he arranged to be posted as a military surgeon to the East Indies -

xxxxxGiven the support of the Dutch government, who provided him with two assistants and a labour force, he began by excavating caves on the island of Sumatra, but he found nothing of real value, and his research was hampered by the dense jungle of the terrain. In 1890, having learnt that a mining engineer had found a human skull at Wadjak in Java, he moved to this island and began searching among the fossil-

xxxxxGiven the support of the Dutch government, who provided him with two assistants and a labour force, he began by excavating caves on the island of Sumatra, but he found nothing of real value, and his research was hampered by the dense jungle of the terrain. In 1890, having learnt that a mining engineer had found a human skull at Wadjak in Java, he moved to this island and began searching among the fossil-

xxxxxHe published his findings in 1894 and returned to Europe the following year. As one would expect, his claim was totally dismissed by the Creationists (those believing that the earth was created by a supernatural power), but a large number of scientists who supported evolution, while applauding his work, questioned his interpretation. Much doubt was expressed as to whether the skullcap and the femur had come from the same individual; some thought the skullcap might be that of a giant gibbon (though it was clearly too big for that); and others tended to see the creature as an early human. Dubois toured Western Europe vigorously defending his claim. Hisxcase was not helped, nor his frame of mind, however, when one critic maintained that some of the teeth were from an orang-

xxxxxIn 1900, weary and embittered by the controversy, Dubois refused to discuss the matter further, hid the fossils in his home, and, turning to other research, studied the growth relationship between the size of the brain and body, and conducted an investigation into the climate of the geological past. He did make the fossils available in the early 1930s, but he still insisted that he had found the missing link on the evolutionary scale. It was not until after his death in 1940 that finds of an earlier creature in Africa and additional fossils in Java confirmed that Java Man was in fact the first example to be found of the early species Homo erectus. Its classification was changed accordingly.

xxxxxDubois was the first man to go out deliberately in search of hominid fossils, and he was the first man to find such remains outside of Africa and Europe. In 1897 he was awarded an honorary doctorate in botany and zoology by the University of Amsterdam, and he became professor of geology at the  university in 1899.

university in 1899.

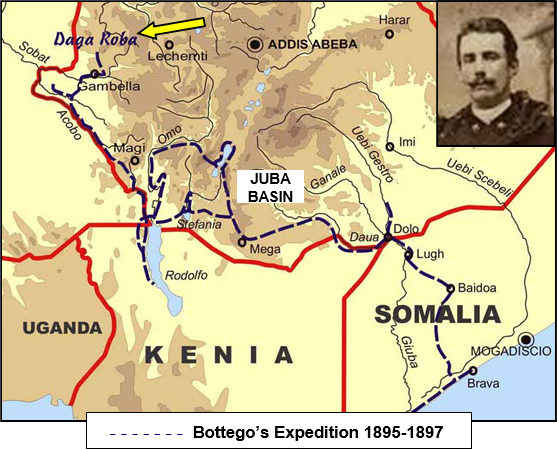

xxxxxIncidentally, worthy of mention here is the Italian explorer Vittorio Bottego (1860-

Vc-