xxxxxThe Dreyfus

Affair, a bitter controversy that deeply divided French society,

began in 1894

with the conviction of a young Jewish army officer, Albert Dreyfus

(1859-1935), on a charge of treason. He was deported to the

French colony of Guiana, and his arrest unleashed a wave of anti-Jewish

propaganda, fanned by powerful anti-Semitic feeling within

the army and the Catholic Church. Two years later, however, fresh

evidence suggested that he was innocent, and that a fellow

officer, Major Marie Charles Esterhazy, had been the German spy.

The French high command, however, was not prepared to reopen the

case, and this caused a wave of protest from liberal, republican

elements, plunging the country into the worst political and social

flare-up in the history of the Third Republic. Eventually

Esterhazy was brought to trial, but when he was acquitted in

January 1898 further demonstrations broke out. It was then that

the French novelist Émil Zola wrote his open letter (J’accuse)

to the French President. Published in L’Aurore,

it accused the army leaders and the War Office of anti-Semitism,

and of covering-up a clear case of injustice. He was charged

with libel and was forced to take refuge in England, but his

letter proved the turning point. Dreyfus was given a retrial and

when, despite everything, he was still found guilty, the

government intervened, quashed the verdict and pardoned him in

1899. He was fully reinstated in 1906. The Dreyfus Affair had

serious consequences. Both the army and the Catholic Church were

discredited and lost much of their political influence, and

republicanism triumphed over monarchism. And the controversy left

deep scars on French political, social and intellectual life, and

the anti-Semitism it displayed took long to live down in a

nation dedicated to liberty, equality and fraternity.

THE DREYFUS AFFAIR 1894 -

1906 (Vc, E7)

Acknowledgements

Dreyfus: c1890,

photographer unknown – The Museum of the Art and History of

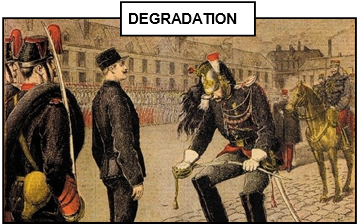

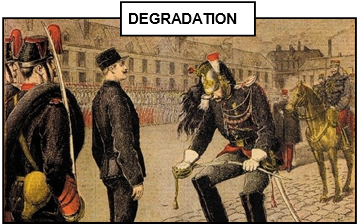

Judaism, Paris. Degradation: detail of

engraving by the French artist Henri Meyer (1844-1899), front

cover of a supplement to the daily Parisian newspaper Le

Petit Journal, January 1895 – Lorraine Beitler Collection

of the Dreyfus Affair, Rare Book and Manuscript Library,

University of Pennsylvania, USA. Esterhazy:

detail of a caricature by the French illustrator Jean Baptiste

Guth (active 1883-1921), published in the British weekly

magazine Vanity Fair (1868-1914) in

May 1898. France: by the French portrait

photographer Wilhelm Benque (1843-1903) – Tucker Collection,

Archives, New York Public Library.

xxxxxThe Dreyfus Affair, a bitter controversy centred

around the conviction of a Jewish French army officer on a charge

of treason, deeply divided French society, and plunged the country

into the worst political and social flare-up in the history

of the Third Republic. Its consequences were significant and long

lasting. It thrust the republican wing of political life into a

dominant position, undermined the standing of the army, and

eventually led to the separation of Church and State.

xxxxxItxwas in 1893 that a young

artillery captain of Jewish faith named Alfred

Dreyfus (1859-1935), on the staff

at the War Ministry, was accused of having written a document

betraying secret information to the German military attaché in

Paris. In November 1894,

despite the lack of conclusive evidence

and his strong denial of the charge, he was found guilty by a

court martial, ceremoniously reduced in rank (illustrated), and sentenced to

life imprisonment on Devil’s Island, a penal settlement off the

coast of French Guiana. The matter might well have ended there, but

two years later the new chief of military intelligence, a Lieutenant

Colonel George Picquart, uncovered evidence to suggest that, in

fact, the document had not been written by Dreyfus, but by a French

infantry officer named Major Marie Charles Esterhazy. The French

high command, however, not wishing to reopen the matter and have

questions raised as to their competence and racial

bias, ignored Picquart’s suggestion, posted him to Tunisia,

and had forged documents made to strengthen the original verdict.

xxxxxItxwas in 1893 that a young

artillery captain of Jewish faith named Alfred

Dreyfus (1859-1935), on the staff

at the War Ministry, was accused of having written a document

betraying secret information to the German military attaché in

Paris. In November 1894,

despite the lack of conclusive evidence

and his strong denial of the charge, he was found guilty by a

court martial, ceremoniously reduced in rank (illustrated), and sentenced to

life imprisonment on Devil’s Island, a penal settlement off the

coast of French Guiana. The matter might well have ended there, but

two years later the new chief of military intelligence, a Lieutenant

Colonel George Picquart, uncovered evidence to suggest that, in

fact, the document had not been written by Dreyfus, but by a French

infantry officer named Major Marie Charles Esterhazy. The French

high command, however, not wishing to reopen the matter and have

questions raised as to their competence and racial

bias, ignored Picquart’s suggestion, posted him to Tunisia,

and had forged documents made to strengthen the original verdict.

xxxxxAt the same

time, however, evidence implicating Esterhazy had come to the

knowledge of the Dreyfus family and a number of his friends. As a

result, Dreyfus' brother Mathieu succeeded in having Esterhazy

brought to trial in 1897. But Despite the new evidence available,

the court martial acquitted Esterhazy of alleged forgery early in

1898. By that time, through rumour and evidence passed to the

Press, much of the detail surrounding the case had leaked out, and

the Dreyfus Affair, as it came to be known, had become a highly

divisive issue in French society.

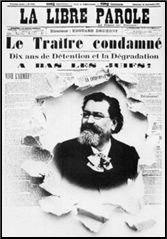

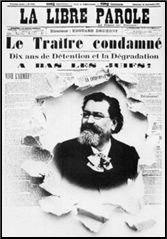

xxxxxWhen Dreyfus was originally found guilty the news

unleashed a wave of anti-Jewish propaganda. Fanned by

powerful anti-Semitic feeling - ever present in both the

French army and the Catholic Church - it surprised many by

its strength and its extent. There were rallies decrying the Jews

in Paris and throughout the provinces, and many, like Édouard

Drumont, the editor of the newspaper La Libre

Parole, saw Dreyfus as typifying the disloyalty of French

Jews as a whole. At first, given Dreyfus’ apparent guilt -

decided in camera, be it noted - liberal factions were

obliged to remain silent, but with the discovery of the evidence

against Esterhazy,

followed by the summary dismissal of his accuser and the acquittal

of Esterhazy, the mood changed rapidly. There now came a volume of

protest across the country against what was seen as a clear case

of injustice, accompanied by a vociferous demand for a retrial of

Dreyfus to right the wrong. Very soon France was bitterly divided

between those who upheld the sentence imposed on the young Jewish

officer - the right-wing conservative elements, the army

and the Roman Catholic Church - and those who were convinced

that he was innocent, a victim of racial prejudice - the

liberal politicians, the radical republicans and the intellectual

élite.

xxxxxWhen Dreyfus was originally found guilty the news

unleashed a wave of anti-Jewish propaganda. Fanned by

powerful anti-Semitic feeling - ever present in both the

French army and the Catholic Church - it surprised many by

its strength and its extent. There were rallies decrying the Jews

in Paris and throughout the provinces, and many, like Édouard

Drumont, the editor of the newspaper La Libre

Parole, saw Dreyfus as typifying the disloyalty of French

Jews as a whole. At first, given Dreyfus’ apparent guilt -

decided in camera, be it noted - liberal factions were

obliged to remain silent, but with the discovery of the evidence

against Esterhazy,

followed by the summary dismissal of his accuser and the acquittal

of Esterhazy, the mood changed rapidly. There now came a volume of

protest across the country against what was seen as a clear case

of injustice, accompanied by a vociferous demand for a retrial of

Dreyfus to right the wrong. Very soon France was bitterly divided

between those who upheld the sentence imposed on the young Jewish

officer - the right-wing conservative elements, the army

and the Roman Catholic Church - and those who were convinced

that he was innocent, a victim of racial prejudice - the

liberal politicians, the radical republicans and the intellectual

élite.

xxxxxThexjournalist and left-wing

politician George Clemenceau (1841-1929) was one of the first to come to the

support of Dreyfus. He began an eight-year campaign to see

justice done, waged via the columns of his two newspapers La

Justice and L’Aurore. His

political connections and his close friendship with the best-known

writers and artists of the day gained him widespread backing for

the cause. But it was one of his literary friends, the novelist Émil Zola, who more than any

other person galvanised support. On the 13th January 1898, just a

few days after Esterhazy had been acquitted, he published an open

letter to the French president (Félix Faure) on the front page of

the daily L’Aurore. Now known the world

over as “J’accuse” (the opening words)

it was a fierce denunciation of the French general staff. In it,

he charged a number of high-ranking officers and the War

Office itself of anti-Semitism, and of deliberately

attempting to cover up a miscarriage of justice. It was a

courageous, impassioned attack and, by evening, 200,000 copies of

the newspaper had been sold. The letter proved a turning point in

the affair, made the more so by the punishment metered out to Zola

as a consequence. He was found guilty of libel, fined 3,000

francs, and sentenced to a year in prison. However, when his

appeal against the verdict looked likely to fail, he fled to

England, and only returned to France in June 1899 after receiving

the promise of an amnesty. Whilst in London his account of the

Dreyfus affair ensured that the matter received even greater

worldwide coverage.

xxxxxThexjournalist and left-wing

politician George Clemenceau (1841-1929) was one of the first to come to the

support of Dreyfus. He began an eight-year campaign to see

justice done, waged via the columns of his two newspapers La

Justice and L’Aurore. His

political connections and his close friendship with the best-known

writers and artists of the day gained him widespread backing for

the cause. But it was one of his literary friends, the novelist Émil Zola, who more than any

other person galvanised support. On the 13th January 1898, just a

few days after Esterhazy had been acquitted, he published an open

letter to the French president (Félix Faure) on the front page of

the daily L’Aurore. Now known the world

over as “J’accuse” (the opening words)

it was a fierce denunciation of the French general staff. In it,

he charged a number of high-ranking officers and the War

Office itself of anti-Semitism, and of deliberately

attempting to cover up a miscarriage of justice. It was a

courageous, impassioned attack and, by evening, 200,000 copies of

the newspaper had been sold. The letter proved a turning point in

the affair, made the more so by the punishment metered out to Zola

as a consequence. He was found guilty of libel, fined 3,000

francs, and sentenced to a year in prison. However, when his

appeal against the verdict looked likely to fail, he fled to

England, and only returned to France in June 1899 after receiving

the promise of an amnesty. Whilst in London his account of the

Dreyfus affair ensured that the matter received even greater

worldwide coverage.

xxxxxMeanwhile,

in August 1898 a new revelation added fuel to the burning issue.

Picquart’s successor as head of intelligence, a Lieutenant Colonel

Hubert-Joseph Henry, admitted that he had forged documents in

order to implicate Dreyfus. He was arrested, but committed suicide

whilst in custody. On the strength of this confession Esterhazy

was dismissed from the army. He beat a hasty retreat to England,

leaving France in turmoil. Unruly demonstrations and counter-demonstrations

took place across the country, and the funeral of president Faure

in February 1899 - a man who had always opposed a retrial -

was the scene of an ugly disturbance between the pro and anti

Dreyfus groups. Eventually in June the liberal politician René

Waldeck-Rousseau was asked to form a coalition government.

Resolved to bring the affair to an end before a complete breakdown

of law and order, he sanctioned a retrial. A second court martial

was held at Rennes in September 1899, but, despite the new

evidence, Dreyfus was again found guilty of treason, his term of

imprisonment being reduced to ten years because of “extenuating

circumstances”. The verdict caused widespread anger among the pro-Dreyfusards

and threatened further trouble, but ten days later the government

intervened. The verdict of the court was quashed and Dreyfus was

given a presidential pardon.

xxxxxIt was not,

however, until July 1906 that the Court of Appeal exonerated

Dreyfus and reversed all previous convictions against him. He was

readmitted to the army with the rank of major, awarded the Legion

of Honour, and went on to serve in the First World War. He

attained the rank of lieutenant colonel, retired after the war,

and died in 1935. He was buried in Montparnasse cemetery in Paris.

xxxxxThe Dreyfus Affair went far deeper than simply the

matter of the guilt or the innocence of a young army officer of

Jewish descent. First and perhaps foremost, it revealed the

powerful strain of anti-Semitism running throughout French

society - surprisingly strong in a nation dedicated to

liberty, equality and fraternity. Secondly, it polarized the

country’s political make-up in the wake of the humiliation of

the Franco-PrussIan War and the overthrow of the Emperor. For

the pro-Dreyfusards - the republicans and the socialists

- the issue at stake was the freedom of the individual and

the survival of the Republic. For the anti-Dreyfusards -

the conservative, military and Catholic forces (monarchists at

heart) - the need was to defend the authority of the army and

state against socialism and the dangers, as they saw it, posed by

international Jewry.

xxxxxThe Dreyfus Affair went far deeper than simply the

matter of the guilt or the innocence of a young army officer of

Jewish descent. First and perhaps foremost, it revealed the

powerful strain of anti-Semitism running throughout French

society - surprisingly strong in a nation dedicated to

liberty, equality and fraternity. Secondly, it polarized the

country’s political make-up in the wake of the humiliation of

the Franco-PrussIan War and the overthrow of the Emperor. For

the pro-Dreyfusards - the republicans and the socialists

- the issue at stake was the freedom of the individual and

the survival of the Republic. For the anti-Dreyfusards -

the conservative, military and Catholic forces (monarchists at

heart) - the need was to defend the authority of the army and

state against socialism and the dangers, as they saw it, posed by

international Jewry.

xxxxxFollowing

the vindication of Captain Dreyfus - a victory for republican

ideals encapsulated in the rights of man - the power and the

prestige of the military and of the Catholic Church declined in

France. The army - the bastion of monarchism - was

discredited beyond total repair and put under civilian control,

whilst the introduction of anti-clerical legislation

eventually led to the separation of church and state in 1905, and

a consequent reduction in the role of religion in political

affairs. A political format was eventually reached, but the bitter

controversy aroused by the Dreyfus Affair, rumbling on over twelve

years, left deep scars on French political, social and

intellectual life, and these took more than a generation to heal.

xxxxxIncidentally, Esterhazy (illustrated) later confessed

to being a German spy and li ved

out his life in England, supported by the donations of anti-Semitics.

He worked as a translator, using the name Count Jean de Voilement,

and died in Harpenden, Hertfordshire, in 1923. Colonel Picquart was

reinstated, promoted to general, and served as war minister in the

government of prime-minister Georges Clemenceau from 1906 to 1909. As noted earlier, Zola died in

1902, killed by the fumes from a bedroom fire. It was officially

seen as an accident, but many believed that the chimney had been

blocked up deliberately by anti-Dreyfusards as an act of

revenge for his crucial support of the young Jewish officer. ……

ved

out his life in England, supported by the donations of anti-Semitics.

He worked as a translator, using the name Count Jean de Voilement,

and died in Harpenden, Hertfordshire, in 1923. Colonel Picquart was

reinstated, promoted to general, and served as war minister in the

government of prime-minister Georges Clemenceau from 1906 to 1909. As noted earlier, Zola died in

1902, killed by the fumes from a bedroom fire. It was officially

seen as an accident, but many believed that the chimney had been

blocked up deliberately by anti-Dreyfusards as an act of

revenge for his crucial support of the young Jewish officer. ……

xxxxx…… Likexxmany

Jews at the time, the Austro-Hungarian journalist Theodor Herzl (1860-1904)

was surprised and alarmed at the amount of anti-Semitism that

the Dreyfus Affair revealed at all levels of French society. He

witnessed mass rallies in Paris where many chanted “Death to the

Jews”. He later explained that it was this aspect of the Dreyfus

Affair (together with the anti-Jewish pogroms in Russia) that

prompted him to found the Zionist Movement in

1897, an organisation in favour of the re-establishment of a

Jewish Homeland in Palestine. Given the extent of anti-Semitism

that existed above and below the surface, he came to realise that

assimilation was impossible, and that the only solution for the

Jews would be the creation of a Jewish state. ……

xxxxx…… Likexxmany

Jews at the time, the Austro-Hungarian journalist Theodor Herzl (1860-1904)

was surprised and alarmed at the amount of anti-Semitism that

the Dreyfus Affair revealed at all levels of French society. He

witnessed mass rallies in Paris where many chanted “Death to the

Jews”. He later explained that it was this aspect of the Dreyfus

Affair (together with the anti-Jewish pogroms in Russia) that

prompted him to found the Zionist Movement in

1897, an organisation in favour of the re-establishment of a

Jewish Homeland in Palestine. Given the extent of anti-Semitism

that existed above and below the surface, he came to realise that

assimilation was impossible, and that the only solution for the

Jews would be the creation of a Jewish state. ……

xxxxx…… The Dreyfus Affair overshadowed and served to

distract public attention from the Fashoda Crisis, a military

confrontation between French and British forces in the Sudan in 1898 which, as we shall

see, could easily have ended in a full-scale war. The fact

that it didn’t may have been influenced to some degree by the

government’s preoccupation with matters nearer to home.

Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc

Including:

Émile Zola and

Anatole France

xxxxxAmong the

many intellectuals who supported Dreyfus was the French novelist,

poet and critic Anatole France (1844-1924). He wrote a vast number of works, but

is mostly remembered today for his novels, including

The Crime of Sylvester Bonnard, My

Friend’s Book, Thaïs, Penguin

Island, The Gods are

Athirst, and his Contemporary History,

a four volume work in which he exposed the social and political

shortcomings highlighted by the Dreyfus Affair. His works were

admired for the clarity of their prose and verse, and for the

satirical attack they launched upon the failings within the Church

and State of his day. In his later years, embittered and more

pessimistic, he turned his attention to social affairs, supporting

civil liberties and the rights of the working man, and attacking

bourgeois values. A well respected man of letters, he was admitted

to the Académie Française in 1896 and awarded the Nobel Prize for

literature in 1921. He worked as a librarian at the French Senate

for fourteen years, and was one time literary critic for the

newspaper Le Temps. He was born Jacques-François-Anatole

Thibault, and took his pen name from the bookshop, the Librairie

de France, that his father owned in Paris.

xxxxxAmong the large number of French intellectuals who

came to the defence of Dreyfus - including the poet Charles

Péguy and the writer Marcel Proust - was the French novelist,

poet, and critic Anatole France (1844-1924). He was the first to sign Zola’s manifesto supporting

Dreyfus, and he wrote about the affair in his novel Monsieur

Bergeret in Paris, published in 1901. In this work the

hero, France himself in fact - a hitherto detached observer

of political and social life - throws himself whole heartedly

into the struggle to prove the innocence of this young Jewish

officer.

xxxxxAmong the large number of French intellectuals who

came to the defence of Dreyfus - including the poet Charles

Péguy and the writer Marcel Proust - was the French novelist,

poet, and critic Anatole France (1844-1924). He was the first to sign Zola’s manifesto supporting

Dreyfus, and he wrote about the affair in his novel Monsieur

Bergeret in Paris, published in 1901. In this work the

hero, France himself in fact - a hitherto detached observer

of political and social life - throws himself whole heartedly

into the struggle to prove the innocence of this young Jewish

officer.

xxxxxFrance was

born in Paris, the son of a bookseller, and this accounts for his

love of books and the depth of his reading. After receiving a

fairly good grounding in the classics at the College Stanislas, a

private Catholic school, he decided to devote his life to

literature. At first, however, he was obliged to make a living.

For the next twenty years - save for a brief period of

military service in the Franco-Prussian War - he took on

a variety of jobs. He assisted his father in his shop for a while,

did some teaching, and then worked in journalism as a publisher’s

reader and critic. Then in 1876 he was appointed assistant

librarian at the French Senate, a post he held for fourteen years,

and in 1888 he started writing a regular weekly column as the

literary critic for the prestigious newspaper Le

Temps.

xxxxxBut he never let employment get in the way of his

writing. His output was vast and included novels, short stories,

verse, drama, historical works and critical and philosophical

essays and articles. Today, however, he is chiefly remembered as a

novelist and story teller. His first work of importance was a

critical study of the French poet Alfred de Vigny in 1869, and he

followed this up in the 1870s with a volume of poetry, Golden

Tales, a verse drama entitled The

Bride of Corinth, and his first collection of short

stories, Jocasta and the Thin Cat. But

it was the publication of his first novel in 1881, The

Crime of Sylvester Bonnard, that brought him the

beginning of fame and fortune. A nostalgic look-back at what

he saw as the golden age of the 18th century, it displayed the

graceful, elegant prose, the subtle but sharp irony (reminiscent

of Voltaire),

and the genuine human sympathy that were to become the hallmarks

of his writing. It won him a prize from the Académie

Française, and began a production of novels which made

him one of the leading figures of French literature in the late

19th and early 20th centuries. In nearly all of these works he

took a cynical, pessimistic view of contemporary society, aiming

much of his shrewd criticism at what he saw as the failings within

Church and State.

xxxxxBut he never let employment get in the way of his

writing. His output was vast and included novels, short stories,

verse, drama, historical works and critical and philosophical

essays and articles. Today, however, he is chiefly remembered as a

novelist and story teller. His first work of importance was a

critical study of the French poet Alfred de Vigny in 1869, and he

followed this up in the 1870s with a volume of poetry, Golden

Tales, a verse drama entitled The

Bride of Corinth, and his first collection of short

stories, Jocasta and the Thin Cat. But

it was the publication of his first novel in 1881, The

Crime of Sylvester Bonnard, that brought him the

beginning of fame and fortune. A nostalgic look-back at what

he saw as the golden age of the 18th century, it displayed the

graceful, elegant prose, the subtle but sharp irony (reminiscent

of Voltaire),

and the genuine human sympathy that were to become the hallmarks

of his writing. It won him a prize from the Académie

Française, and began a production of novels which made

him one of the leading figures of French literature in the late

19th and early 20th centuries. In nearly all of these works he

took a cynical, pessimistic view of contemporary society, aiming

much of his shrewd criticism at what he saw as the failings within

Church and State.

xxxxxHis

writings of the late 1880s and early 1990s, included his critical

essays, La vie littéraire in four

volumes, and the novels Balthazar, a

fanciful tale centred around one of the Magi; Thaïs,

a denunciation of asceticism, set in Egypt in the early Christian

era; The Opinions of Mr. Jérôme Coignard,

and At the Sign of the Reine Pédauque -

both exposing human frailty from a detached view point - and

The Red Lily, a tragic love story played

out in Florence. And to this period belongs My

Friend’s Book, the first of his semi-autobiographical

series.

xxxxxBy the mid-1890s,

however, there was a noticeable change in emphasis. Following the

outbreak of the Dreyfus Affair, beginning in earnest in 1896 (the

year France was admitted to the Académie

Française), France became progressively disillusioned,

and his view of life more embittered. He now turned his attention

to social affairs, such as civil liberties and the rights of the

working man, and in so doing, launched a more bitter attack upon

society as a whole and the Church and the political establishment

in particular. And his open hostility towards bourgeois values led

him to embrace socialism and, eventually, communism. His Contemporary

History, for example, four prose works spanning 1897 to

1901, made much of the social and political shortcomings

highlighted by the Dreyfus Affair, as did his three act comedy Crainquebill of 1903, his satirical

allegory Penguin Island of 1908, and his realistic fantasy The

Revolt of the Angels of 1914. And to this period belongs

one of his best known works, Les Dieux en

Soif (The Gods are

Athirst), a powerful condemnation of fanaticism set in

the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution. The warnings

were not heeded in his own time, however, and the horrors of the

First World War only served to increase his pessimism. As a means

of relief, he turned to completing his childhood reminiscences in

Little Pierre and The

Bloom of Life, completed two years before his death.

xxxxxFrance was

awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1921 in recognition of

his brilliant literary achievements and the classical clarity of

his prose and verse. He used wit, satire and irony to expose the

failings of contemporary society and to serve his passion for

social justice. He had a profound sympathy for the condition of

human society, and his scholarship, remarkable in its breadth,

marked him out as a well-respected man of letters. He died in

Tours, and was buried at Neuilly cemetery in the western suburbs

of Paris.

xxxxxIncidentally, France was born Jacques-Francois-Anatole

Thibault, and took his pen name from the name of his father’s

bookshop, the Librairie de France in Paris. ……

xxxxx…… His marriage to Marie-Valerie Guerin de Sauville

in 1877 ended in divorce in 1893. Before then, however, he had

formed an intimate friendship with Madame Arman de Caillavet. She

had a celebrated literary salon, promoted his works through her

many social contacts, and was the inspiration for his novels Thaïs and The Red Lily.

……

xxxxx…… As noted later, his novel Thaïs

was made into an opera by the French composer Jules Massenet and

was first performed in Paris in 1894.

xxxxxItxwas in 1893 that a young

artillery captain of Jewish faith named Alfred

Dreyfus (1859-

xxxxxItxwas in 1893 that a young

artillery captain of Jewish faith named Alfred

Dreyfus (1859- xxxxxWhen Dreyfus was originally found guilty the news

unleashed a wave of anti-

xxxxxWhen Dreyfus was originally found guilty the news

unleashed a wave of anti- xxxxxThexjournalist and left-

xxxxxThexjournalist and left- xxxxxThe Dreyfus Affair went far deeper than simply the

matter of the guilt or the innocence of a young army officer of

Jewish descent. First and perhaps foremost, it revealed the

powerful strain of anti-

xxxxxThe Dreyfus Affair went far deeper than simply the

matter of the guilt or the innocence of a young army officer of

Jewish descent. First and perhaps foremost, it revealed the

powerful strain of anti- ved

out his life in England, supported by the donations of anti-

ved

out his life in England, supported by the donations of anti- xxxxx…… Likexxmany

Jews at the time, the Austro-

xxxxx…… Likexxmany

Jews at the time, the Austro-

xxxxxAmong the large number of French intellectuals who

came to the defence of Dreyfus -

xxxxxAmong the large number of French intellectuals who

came to the defence of Dreyfus - xxxxxBut he never let employment get in the way of his

writing. His output was vast and included novels, short stories,

verse, drama, historical works and critical and philosophical

essays and articles. Today, however, he is chiefly remembered as a

novelist and story teller. His first work of importance was a

critical study of the French poet Alfred de Vigny in 1869, and he

followed this up in the 1870s with a volume of poetry, Golden

Tales, a verse drama entitled The

Bride of Corinth, and his first collection of short

stories, Jocasta and the Thin Cat. But

it was the publication of his first novel in 1881, The

Crime of Sylvester Bonnard, that brought him the

beginning of fame and fortune. A nostalgic look-

xxxxxBut he never let employment get in the way of his

writing. His output was vast and included novels, short stories,

verse, drama, historical works and critical and philosophical

essays and articles. Today, however, he is chiefly remembered as a

novelist and story teller. His first work of importance was a

critical study of the French poet Alfred de Vigny in 1869, and he

followed this up in the 1870s with a volume of poetry, Golden

Tales, a verse drama entitled The

Bride of Corinth, and his first collection of short

stories, Jocasta and the Thin Cat. But

it was the publication of his first novel in 1881, The

Crime of Sylvester Bonnard, that brought him the

beginning of fame and fortune. A nostalgic look-