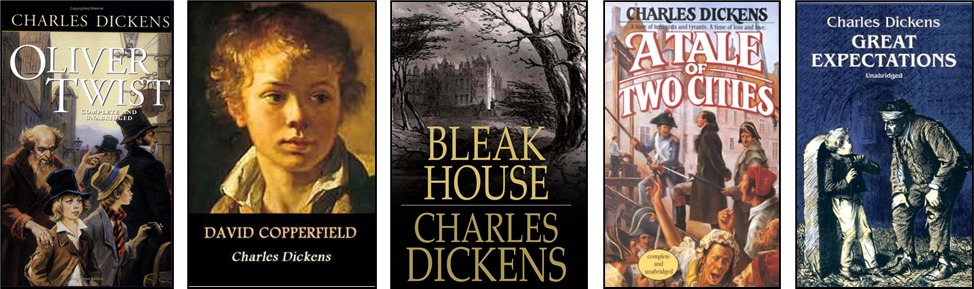

xxxxxCharles Dickens, one of the greatest English storytellers, began his writing career as a London journalist. He gained almost overnight fame with his amusing serial story The Pickwick Papers, begun in 1836, and then wrote a stream of novels, beginning with Oliver Twist in 1837. Among these were Nicholas Nickleby, The Old Curiosity Shop, Barnaby Rudge, David Copperfield (perhaps his best loved story, produced in 1850), Bleak House, the historical tragedy A Tale of Two Cities, and Great Expectations, considered by many as his finest work. Many of the tales in this kaleidoscope of compelling stories, though often witty in parts, were designed to expose the hard, wretched life endured by the working classes in London -

CHARLES JOHN HUFFHAM DICKENS 1812 -

(G3c, G4, W4, Va, Vb)

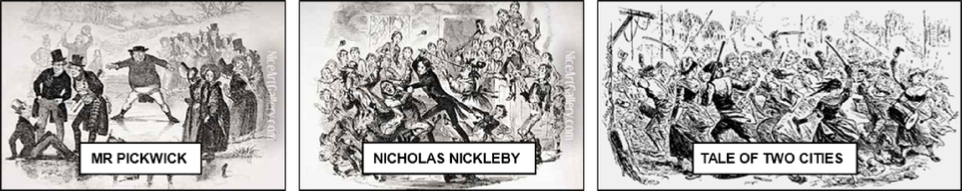

xxxxxCharles Dickens, arguably the greatest of all English novelists, began his series of “reforming novels” with Oliver Twist in 1837, and followed this up with Nicholas Nickleby a year later, The Old Curiosity Shop in 1840, Barnaby Rudge in 1841, and Dombey and Son in 1848. Perhaps his best loved work, and certainly his own favourite, was David Copperfield, published in 1850. Later works included Bleak House in 1853, the historical tragedy A Tale of Two Cities in 1859, and another of his much admired stories, Great Expectations, produced two years later and judged by many to be his finest work. But it was The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club with their highly amusing stories of Mr. Pickwick, his close friends, and his ever faithful servant Sam Weller, which proved so popular, made him famous, and set him on his successful career at the age of 24.

xxxxxCharles Dickens, arguably the greatest of all English novelists, began his series of “reforming novels” with Oliver Twist in 1837, and followed this up with Nicholas Nickleby a year later, The Old Curiosity Shop in 1840, Barnaby Rudge in 1841, and Dombey and Son in 1848. Perhaps his best loved work, and certainly his own favourite, was David Copperfield, published in 1850. Later works included Bleak House in 1853, the historical tragedy A Tale of Two Cities in 1859, and another of his much admired stories, Great Expectations, produced two years later and judged by many to be his finest work. But it was The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club with their highly amusing stories of Mr. Pickwick, his close friends, and his ever faithful servant Sam Weller, which proved so popular, made him famous, and set him on his successful career at the age of 24.

xxxxxDickens was born in Portsea, Hampshire, the son of a clerk in the Navy’s pay office there. He attended the local school, but at the age of eleven his father -

xxxxxAfter returning to school, following his father’s release, he became a lawyer’s clerk at the age of sixteen and then, four years later, discovered his talent while working as a court and parliamentary reporter for the Morning Chronicle. It was then that he started writing short sketches about life in London for The Monthly Magazine, writing under the name of “Boz”, and it was this series of articles which led to his creation of Mr Pickwick and his hilarious adventures. The “Pickwick Papers”, published in monthly instalments, proved immensely popular, established his reputation, and made him a household word almost over night. We are told that when first published in May 1836 only 400 copies were produced; by the fourth instalment some 40,000 were needed.

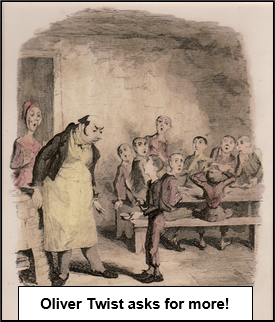

xxxxxIt says much for his skill and versatility as a writer, that having made his mark in comedy, he then produced a string of reforming novels designed to expose in graphic detail the social evils that lurked below the surface of a seemingly prosperous Victorian England. Using his talent as a master storyteller, he highlighted the poverty, slums, disease and child labour endured by the poor and disadvantaged, be it the horrors of the workhouse, as in Oliver Twist, the cruelty of teachers within boarding schools, as in his melodrama Nicholas Nickleby, the corruption of the judicial system, as in Bleak House, the abuse of the prison system, as in Little Dorrit, or the plight of the industrial workers or “hands”, as in Hard Times. These social tracts, published in serial form like a dripping tap, forced all the ranks of Victorian society to confront these issues of exploitation and social injustice, and contributed in large measure to the philanthropic movement which developed throughout the country over the remainder of the century.

xxxxxIt says much for his skill and versatility as a writer, that having made his mark in comedy, he then produced a string of reforming novels designed to expose in graphic detail the social evils that lurked below the surface of a seemingly prosperous Victorian England. Using his talent as a master storyteller, he highlighted the poverty, slums, disease and child labour endured by the poor and disadvantaged, be it the horrors of the workhouse, as in Oliver Twist, the cruelty of teachers within boarding schools, as in his melodrama Nicholas Nickleby, the corruption of the judicial system, as in Bleak House, the abuse of the prison system, as in Little Dorrit, or the plight of the industrial workers or “hands”, as in Hard Times. These social tracts, published in serial form like a dripping tap, forced all the ranks of Victorian society to confront these issues of exploitation and social injustice, and contributed in large measure to the philanthropic movement which developed throughout the country over the remainder of the century.

xxxxxBut along with this serious social commentary went the making of a host of memorable characters, creations of a rich imagination, a wonderful sense of humour, and a memory finely honed to remember detail. Exaggerated though they might be in some cases, the reader was not likely to forget the humble Uriah Heep (illustrated); a Mr Micawber who (like Dicken’s father) was always waiting for something to turn up; a Barkis who was “willin’”; the miser Ebenezer Scrooge, and the carefree valet Sam Weller. And then there were the villains -

Va-

Acknowledgements

Dickens: detail, by the English painter William Powell Frith (1819-

xxxxxHowever, these main stream novels were by no means his only source of employment. Indeed many of them were published in periodicals of his own making, such as the weekly magazine Master Humphrey’s Clock, started in 1840, and then Household Words, first published in 1850 and replaced with All The Year Round nine years later. These highly popular productions had to be controlled, edited and provided with articles. In addition, for a short time in 1846, he founded and edited his own national newspaper, the Daily News, and while Oliver Twist was being serialised he edited a biography of the English clown Joseph Grimaldi, famous for his performances early in the century.

xxxxxAmong Dicken’s other works was his Christmas stories, starting with his popular A Christmas Carol in 1843, and followed by The Chimes the following year and The Cricket on the Hearth in 1845. For future generations, these conjured up a nostalgic picture of Christmas in Dickensian England, kept alive by cards of seasonal good wishes showing snow scenes, roaring log fires, and horse-

xxxxxAnd as if all this was not enough demand on his time, he was often asked to speak at dinners and fund raising events, and in 1858 he began to give public readings from his novels. These proved extremely successful both at home and in America, with audiences laughing out loud or weeping uncontrollably. And around this time he managed his own theatre company, producing plays and acting in them. This toured the country, and played before Queen Victoria in 1851. Yet he also found time for travel. He lived in Italy for a year, visited France and Switzerland, and travelled twice to America. There, however, he angered many by his blunt denunciation of slavery, and his attack upon American publishers for copying English works. Later he wrote two travel books, American Notes of 1842, and Pictures from Italy of 1846.

xxxxxBut whilst his public life was highly successful, his private life was not without sorrow. He married Catherine Hogarth in 1836, and they had ten children, but in the 1850s his reading tours kept them apart for long periods. Furthermore, in 1857 he met the actress Ellen Ternan and this led to his separation from his wife the following year. His sister-

xxxxxModern TV drama, theatre productions and lavish musicals testify to the endurance of his work. He was a born story teller, and whilst some of his characters came close to caricature, and his pathos was sometimes overdrawn, he produced a stream of novels which enlightened as well as entertained. He had a great empathy with the common man, and his social criticism, sharpened by satire but tempered with humour, made him not only one of the most popular writers in the history of literature, but also one of the most influential. In his work he was clearly influenced by the picaresque novels of Henry Fielding and Tobias Smollett, and among his friends, from the artistic as well as the literary world, were the writers Wilkie Collins and William Makepeace Thackeray, though he quarrelled with the latter in 1858. He suffered a fatal stroke in June 1870, and was buried in Westminster Abbey five days later, mourned by an admiring public.

xxxxxModern TV drama, theatre productions and lavish musicals testify to the endurance of his work. He was a born story teller, and whilst some of his characters came close to caricature, and his pathos was sometimes overdrawn, he produced a stream of novels which enlightened as well as entertained. He had a great empathy with the common man, and his social criticism, sharpened by satire but tempered with humour, made him not only one of the most popular writers in the history of literature, but also one of the most influential. In his work he was clearly influenced by the picaresque novels of Henry Fielding and Tobias Smollett, and among his friends, from the artistic as well as the literary world, were the writers Wilkie Collins and William Makepeace Thackeray, though he quarrelled with the latter in 1858. He suffered a fatal stroke in June 1870, and was buried in Westminster Abbey five days later, mourned by an admiring public.

xxxxxIncidentally, “Boz”, the name by which Dickens signed his short sketches of London, produced in instalments and published as a collection in 1836, was the nickname of his youngest brother. His third Christian name – Huffham (a misspelling on his birth certificate) – was after his godfather, Christopher Huffam, a friend of his father and a prosperous ship rigger in Limehouse. ……

xxxxx…… Conforming with the current belief that magnetic currents had an effect on the working of mind and body, Dickens always sat facing north when he was writing! ……

xxxxx…… A vast number of Dickensian sayings have become part of the English language: such as “The law is an ass -

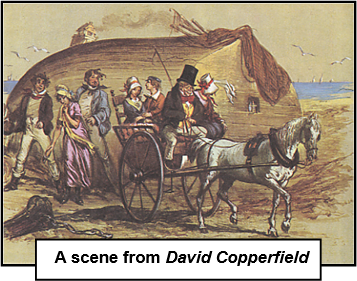

xxxxxDicken’sxnovels were much enhanced by the quality of their illustrations. The picture of Oliver Twist above, asking for more, is an illustration (here coloured) by George Cruikshank, and he also did drawings for Sketches by Boz. His fellow artist John Leech (1817-

xxxxxDicken’sxnovels were much enhanced by the quality of their illustrations. The picture of Oliver Twist above, asking for more, is an illustration (here coloured) by George Cruikshank, and he also did drawings for Sketches by Boz. His fellow artist John Leech (1817-

xxxxxAndxit was at this time that the illustrators John Leech and Hablot Knight Browne worked for the English novelist Robert Smith Surtees (1805-

xxxxxAndxit was at this time that the illustrators John Leech and Hablot Knight Browne worked for the English novelist Robert Smith Surtees (1805-

xxxxxIt was in 1860 that the English writer Wilkie Collins (1824-

xxxxxIt was in 1860, the year that Charles Dickens left London to live in Chatham, that his close friend Wilkie Collins (1824-

xxxxxIt was in 1860, the year that Charles Dickens left London to live in Chatham, that his close friend Wilkie Collins (1824-

xxxxxCollins was born in London, son of William Collins, a landscape painter. Possessed of a lively imagination, he began writing stories while at boarding school. Uncertain as to the career he should follow, and having failed to show any promise in business and the law, he turned to painting and writing. He had a picture accepted by the Royal Academy, but in 1848 he wrote a life of his father and this started him off on his literary career.

xxxxxHis first novel, the historical romance Antonina (or The Fall of Rome), was published two years later, and then in 1851 he met the great novelist Charles Dickens. This was the beginning of a close and long friendship which proved of mutual benefit. They worked together on a number of works, including A Message from the Sea and No Thoroughfare, and, guided by the master, Collins improved his style -

xxxxxHis first novel, the historical romance Antonina (or The Fall of Rome), was published two years later, and then in 1851 he met the great novelist Charles Dickens. This was the beginning of a close and long friendship which proved of mutual benefit. They worked together on a number of works, including A Message from the Sea and No Thoroughfare, and, guided by the master, Collins improved his style -

Including:

Wilkie Collins