xxxxxAs we have seen, Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species aroused bitter controversy, especially among Church leaders, when it was published in 1859 (Va). In that work, Darwin only touched briefly on the sensitive issue of man’s part in the theory of evolution, but in his The Descent of Man of 1871 he discussed the matter in full. Man, he argued, like other species, had descended from some pre-existent form, and was akin to the ape. Despite his noble qualities, his bodily frame bore “the indelible stamp of his lowly origin”. Theologians denounced this theory, as did some scientists. In the second half of the book Darwin expanded on his ideas concerning sexual selection, attempting to show the part played not only by “male combat” in gaining a partner, but also by “mate choice”, based on the ways of attracting female attention by song, colour and other means. He discussed this matter in depth, covering a wide range of species from insects and crustaceans to reptiles and mammals. Later books by Darwin included The Expression of Emotion in Man and Animals, a work which founded ethology (the science of animal behaviour), and the botanical works The Power of Movement in Plants and The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms. And, as we have seen, Darwin also made important contributions in other areas of science, especially in geology. As a leading figure in the field of biology, Darwin was honoured and respected world wide. A man with extraordinary skills of observation, he had the courage to put forward a concept that seemed to degrade man, and was in total conflict with biblical teaching. From his theory, however, stemmed the current theory of evolution, Neo-Darwinism, a synthesis of Darwin’s ideas, and the study of genetics based on the work of the Austrian scientist Gregor Mendel.

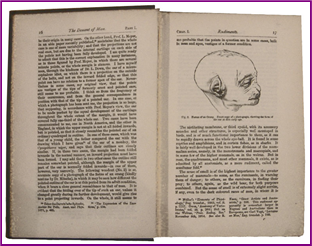

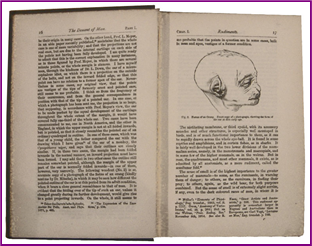

THE DESCENT OF MAN 1871 (Vb)

Acknowledgements

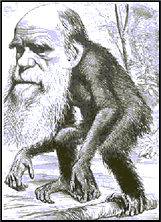

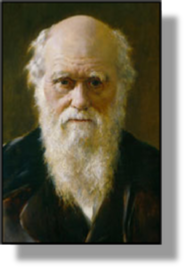

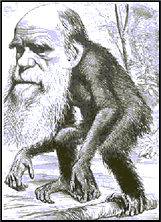

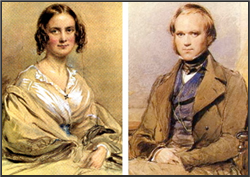

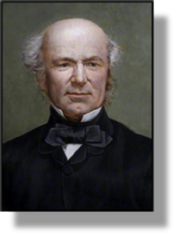

Darwin: detail, by the English artist John Collier (1850-1934), 1883 – National Portrait Gallery, London. Cartoon: originally published in the satirical magazine The Hornet of March 1871 with the caption: A Venerable Orang-Outang: a contribution to unnatural history, artist unknown. Mr and Mrs Darwin: by the English portrait painter George Richmond (1809-1896), 1840 – Down House, Downe, Kent, England, English Heritage Photo Library. Spencer: detail, by the English artist John Bagnold Burgess (1829-1897), 1872 – National Portrait Gallery, London. Hitler: date and artist unknown. Cavern: date and artist unknown – Kents Cavern, Torquay. Pengelly: contemporary portrait, artist unknown – Torquay Museum, Devon, England.

xxxxxAs we have seen, The Origin of Species, published in 1859 (Va) by the English naturalist Charles Darwin, aroused bitter controversy, especially among Church leaders. His theory that life on earth had evolved over millions of years, a thesis developed during his five-year scientific expedition to South America and the Pacific, was diametrically opposed to biblical teaching. This held that the earth was created in 4004 BC and that all living things were specially created by God in their present form. It was a controversy which raged for decades across the western world and was not confined to religious opposition. A number of reputable scientists remained sceptical about Darwin’s ideas of natural selection and the survival of the fittest. However, he was ably supported in his views by his so-called “bulldog”, the English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, and the leading American botanist Asa Gray. Furthermore, the Welsh naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, having arrived at the same theory independently, publicly corroborated Darwin’s findings.

xxxxxAs we have seen, The Origin of Species, published in 1859 (Va) by the English naturalist Charles Darwin, aroused bitter controversy, especially among Church leaders. His theory that life on earth had evolved over millions of years, a thesis developed during his five-year scientific expedition to South America and the Pacific, was diametrically opposed to biblical teaching. This held that the earth was created in 4004 BC and that all living things were specially created by God in their present form. It was a controversy which raged for decades across the western world and was not confined to religious opposition. A number of reputable scientists remained sceptical about Darwin’s ideas of natural selection and the survival of the fittest. However, he was ably supported in his views by his so-called “bulldog”, the English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, and the leading American botanist Asa Gray. Furthermore, the Welsh naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, having arrived at the same theory independently, publicly corroborated Darwin’s findings.

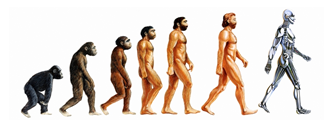

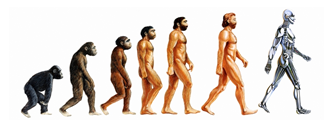

xxxxxThe Origin of Species, “the book that shook the world”, had touched on, albeit briefly, the sensitive issue of man’s part in this theory of evolution, and this had been the cause of much heated debate. In 1871, however, following further research, Darwin added fuel to the controversy with the publication of The Descent of Man, a work in which he attempted to consider more fully “the origin of man and his history” and the theory of “selection in relation to sex”. He argued that man, like other species, had descended from some pre-existent form. He was not descended from apes but had, with them, a common ancestry. Not only were there similarities in body structure and essential organs, but, as in the case of dogs and monkeys, they shared similar mental characteristics such as the ability to love, the power to reason, and sympathy for others. The difference, then, was one of degree, not of kind. Man, he maintained, despite his noble qualities, still bore in his bodily frame “the indelible stamp of his lowly origin”.

xxxxxThe Origin of Species, “the book that shook the world”, had touched on, albeit briefly, the sensitive issue of man’s part in this theory of evolution, and this had been the cause of much heated debate. In 1871, however, following further research, Darwin added fuel to the controversy with the publication of The Descent of Man, a work in which he attempted to consider more fully “the origin of man and his history” and the theory of “selection in relation to sex”. He argued that man, like other species, had descended from some pre-existent form. He was not descended from apes but had, with them, a common ancestry. Not only were there similarities in body structure and essential organs, but, as in the case of dogs and monkeys, they shared similar mental characteristics such as the ability to love, the power to reason, and sympathy for others. The difference, then, was one of degree, not of kind. Man, he maintained, despite his noble qualities, still bore in his bodily frame “the indelible stamp of his lowly origin”.

xxxxxHowever, this argument proved something of a sticking point. It was considered by some, even by those who generally supported the theory of evolution, that the gap in mental ability between man and the smartest ape was too large to be accepted without question. Wallace, much to Darwin’s dismay, went as far as to suggest that the human brain was not due to natural selection, but was an “over-endowment” created by some spiritual force. Andxother scientists questioned the theory on its face value. The English biologist St. George Jackson Mivart (1827-1900), for example, in his Genesis of Species of 1871, denounced Darwin’s thesis as far as human intellect was concerned, and some of the criticism stuck despite a damning review of the book by Thomas Henry Huxley.

xxxxxLikewise, the diverse make-up of the human race raised wider issues. Whilst Darwin insisted that the different human races were not distinct species but simply variants - as in the colour of skin and the texture of hair - there were those who regarded certain peoples as distinct species, created separately and with an inferior capability. And others, whilst not prescribing to this extreme view, saw inherent dangers for the human race if natural selection were not allowed to take its course. The English philosopher Herbert Spencer, for example, feared that helping the weak in society would interfere with the “survival of the fittest” (a term he himself coined) and allow the less fit to succeed at the expense of the more able. And,xarguing along the same lines, Francis Galton (1822-1911) Darwin’s half-cousin and an anthropologist of repute, saw, through the institution of welfare schemes and the care of the mentally retarded, a real danger in the over breeding of the less fit members of society.

xxxxxLikewise, the diverse make-up of the human race raised wider issues. Whilst Darwin insisted that the different human races were not distinct species but simply variants - as in the colour of skin and the texture of hair - there were those who regarded certain peoples as distinct species, created separately and with an inferior capability. And others, whilst not prescribing to this extreme view, saw inherent dangers for the human race if natural selection were not allowed to take its course. The English philosopher Herbert Spencer, for example, feared that helping the weak in society would interfere with the “survival of the fittest” (a term he himself coined) and allow the less fit to succeed at the expense of the more able. And,xarguing along the same lines, Francis Galton (1822-1911) Darwin’s half-cousin and an anthropologist of repute, saw, through the institution of welfare schemes and the care of the mentally retarded, a real danger in the over breeding of the less fit members of society.

xxxxxWhilst showing a degree of understanding towards these concerns, Darwin argued that natural selection in the animal kingdom was not at work in the same way in civilised, human communities. Among human beings there had evolved the instinct of sympathy. This was all part of the scheme of things and could not be checked by any amount of hard reasoning. However, he remained convinced that eventually the less-able, savage races would be forced to give way to the civilised peoples of the world. He saw barbarism as simply an early stage in man’s development.

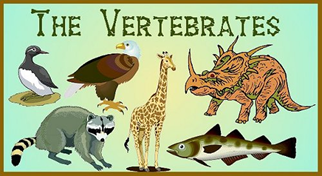

xxxxxThe second half of the book is an expansion of his theory of sexual selection, described by Darwin as the effects of the “struggle between individuals of one sex, generally males, for the possession of the other”, - leading, in consequence, to the propagation of the species. He observed that in a number of species the male did not fight for his choice of female (known as “male combat”), but attracted attention by the power of song or, as in the case of the peacock, by a display of bright colours and patterns (“mate choice”). He discussed this theory at length, maintaining that it played an important part in the history of the organic world. He admitted that in the lower divisions of the animal kingdom sexual selection might not exist, but in the sub-kingdoms of the Vertebrata (such as bony fish, amphibians, reptiles, mammals and birds) and the Arthropoda (such as insects, spiders and crustaceans) he gave detailed examples of what he saw as sexual selection through mutation over many generations. Some of his theories, particularly those dealing with female choice, were rejected by the majority of the scientists of his day, but they have since become more acceptable following a closer study of evolutionary biology.

xxxxxThe second half of the book is an expansion of his theory of sexual selection, described by Darwin as the effects of the “struggle between individuals of one sex, generally males, for the possession of the other”, - leading, in consequence, to the propagation of the species. He observed that in a number of species the male did not fight for his choice of female (known as “male combat”), but attracted attention by the power of song or, as in the case of the peacock, by a display of bright colours and patterns (“mate choice”). He discussed this theory at length, maintaining that it played an important part in the history of the organic world. He admitted that in the lower divisions of the animal kingdom sexual selection might not exist, but in the sub-kingdoms of the Vertebrata (such as bony fish, amphibians, reptiles, mammals and birds) and the Arthropoda (such as insects, spiders and crustaceans) he gave detailed examples of what he saw as sexual selection through mutation over many generations. Some of his theories, particularly those dealing with female choice, were rejected by the majority of the scientists of his day, but they have since become more acceptable following a closer study of evolutionary biology.

xxxxxThe Descent of Man, published in two volumes, was widely read. A reprint was necessary within three weeks, and there were a large number of revised editions, many edited by Darwin himself. Other works published in these later years included The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication, produced in 1868, and The Expression of Emotion in Man and Animals of 1872, a work which, in essence, founded the science of ethology, the study of animal behaviour. Among his botanical works were The Power of Movement in Plants and The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms, both published in the early 1880s. And, as we have seen, Darwin made important discoveries in other areas of science, not least in geology.

xxxxxFollowing on from his Origin of Species, The Descent of Man caught the public imagination and re-vitalised the whole question of evolution. The so-called “missing link” between humans and apes fascinated the popular press, and Thomas Henry Huxley, together with the German zoologist Ernst Haeckel, again found himself in heated discussion with the theologians. And this work, adding further stimulus to biological research, produced new fields of enquiry. These were not always desirable - as in the case of eugenics (the controlled improvement of the human species) - but they contributed in large part to the development of the new science of genetics.

xxxxxFollowing on from his Origin of Species, The Descent of Man caught the public imagination and re-vitalised the whole question of evolution. The so-called “missing link” between humans and apes fascinated the popular press, and Thomas Henry Huxley, together with the German zoologist Ernst Haeckel, again found himself in heated discussion with the theologians. And this work, adding further stimulus to biological research, produced new fields of enquiry. These were not always desirable - as in the case of eugenics (the controlled improvement of the human species) - but they contributed in large part to the development of the new science of genetics.

xxxxxDarwin was one of the world’s greatest figures in the history of biology, and became honoured and respected the world over. A man with a lively curiosity who developed extraordinary skills as both an observer and a theorist, he had the courage to put forward a concept that not only placed humanity on a plane with the animals, but was also in total conflict with the teachings of the established Church at that time. From it stemmed the current theory of evolution. Generally referred to as Neo-Darwinism, this is a synthesis of Darwin’s ideas and the study of genetics, based on the research of the Austrian scientist Gregor Mendel. As a committed scientist, Darwin did not seek controversy, but, given the nature of his thesis, it could hardly be avoided. He died at his home, Down House near Orpington in Kent, in April 1882 and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

xxxxxIncidentally, following his famous voyage aboard the Beagle, Darwin was plagued by ill health. As noted earlier, it seems that while he was in Argentina he had been bitten by an insect that transmits Chagas’s disease, an ailment that causes fatigue and stomach trouble. This illness clearly affected the time he could give over to research. ……

xxxxx…… In April 2008 private papers came to light about Darwin’s views on matrimony. It seems that, scientist to the core, he drew up a pros and cons table before marrying his charming and intelligent cousin Emily Wedgwood in 1839! He feared that marriage might deprive him of valuable research time, oblige him to visit relatives, and take away his bachelor freedom. But the pros won the day. He needed someone to look after the house and care for him in his old age! And then he added: “Only picture to yourself a nice soft wife on a sofa with a good fire and books and music perhaps”. The affectionate and warm hearted Darwin was, in fact, a romantic at heart! The marriage was a success. They had ten children, seven of whom survived childhood.

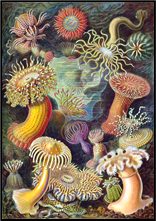

xxxxxA scientist who gave a great deal of support to Darwin’s theory, though not to his ideas on natural selection, was the German zoologist and philosopher Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919). Born in Potsdam, Prussia, he studied at Wurzburg and Berlin, and was appointed professor of comparative anatomy at Jena University in 1865. The following year he met Charles Darwin and it was then that he introduced a method of illustrating evolutionary history by means of treelike diagrams - a method still in use today. He denied the existence of a personal God, arguing that the origin of life was to be found in chemical and physical factors such as oxygen, methane and water. In this connection he coined the term “ecology” - a branch o

xxxxxA scientist who gave a great deal of support to Darwin’s theory, though not to his ideas on natural selection, was the German zoologist and philosopher Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919). Born in Potsdam, Prussia, he studied at Wurzburg and Berlin, and was appointed professor of comparative anatomy at Jena University in 1865. The following year he met Charles Darwin and it was then that he introduced a method of illustrating evolutionary history by means of treelike diagrams - a method still in use today. He denied the existence of a personal God, arguing that the origin of life was to be found in chemical and physical factors such as oxygen, methane and water. In this connection he coined the term “ecology” - a branch o f science dealing with the inter-relationship of organisms and their environments.

f science dealing with the inter-relationship of organisms and their environments.

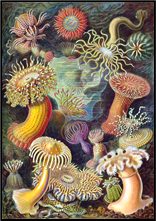

xxxxxDuring his career he produced over a hundred multi-coloured illustrations of various animals and sea creatures, and he named thousands of new species. At one time he attempted to trace the stages in an organism’s evolution by a study of its embryos, but the drawings he produced were later found to be over simplified and inaccurate in some instances. He wrote more than forty books, including Anthropegenie in 1874, Freedom in Science and Teaching, three years later, and The Riddle of the Universe in 1899.

xxxxxIncidentally, Haeckel’s writings and lectures on evolution were later used to justify eugenics and the race doctrine of the Nazi party in Germany before and during the Second World War. This “self direction of human evolution” comes under the general term of “Social Darwinism”, but Darwin himself was utterly opposed to such an idea. ……

xxxxx…… It is said that Haeckel was the first person to refer to the Great War of 1914-1918 by the term “The First World War”. Writing in 1918 he described the European conflict as being the first world war “in the full sense of the word”.

Including:

Ernst Haeckel and

Herbert Spencer

Vb-1862-1880-Vb-1862-1880-Vb-1862-1880-Vb-1862-1880-Vb-1862-1880-Vb-1862-1880-Vb

xxxxxA man who rivalled Charles Darwin in importance during his life time was the English philosopher Herbert Spencer (1820-1903). In his major work System of Synthetic Philosophy (1862-1893) he argued that everything in the universe was subject to the law of evolution. Thus in making a study of human society - known as Social Darwinism - he contended that, by the workings of the survival of the fittest, weak societies would be eliminated, strong ones would survive, and the perfect society would eventually be achieved. This being the case, evolution must be allowed to take its course without interference. He thus favoured a policy of laissez-faire, and advocated the abolition of poor laws, national education and any other means by which the less able were being assisted. Spencer wrote on wide range of subjects, including ethics, religion economics, politics and psychology.

xxxxxA man whose reputation at this time rivalled that of Charles Darwin, was the English philosopher of biological and social evolution Herbert Spencer (1820-1903). An authoritative writer on a vast range of subjects - including ethics, economics, religion, politics and psychology - he was one of the foremost thinkers of the latter part of the 19th century and gained an enormous public following. His major work, the ten-volume System of Synthetic Philosophy, was begun in 1862 and took over thirty years to complete. This attempted to apply the evolutionary theory to all existing fields of knowledge.

xxxxxA man whose reputation at this time rivalled that of Charles Darwin, was the English philosopher of biological and social evolution Herbert Spencer (1820-1903). An authoritative writer on a vast range of subjects - including ethics, economics, religion, politics and psychology - he was one of the foremost thinkers of the latter part of the 19th century and gained an enormous public following. His major work, the ten-volume System of Synthetic Philosophy, was begun in 1862 and took over thirty years to complete. This attempted to apply the evolutionary theory to all existing fields of knowledge.

xxxxxSpencer was born in Derby, the eldest of nine children but the only one to survive infancy. He was largely self taught, and from an early age showed an independent spirit and a marked resistance to authority. He first worked on the engineering staff of the London and Birmingham Railway, but in his early twenties he became more and more involved in journalism and political writing. He was appointed sub- editor of The Economist in 1848 and held this post for five years.

xxxxxIn 1851 he published Social Statics and this, together with his Principles of Psychology produced four years later, convinced him that everything within the universe - be it the galaxies, biological organisms or the human mind - was governed by a universal law based on the principle of evolution, a long-term progressive development. Thusxpersuaded, he turned to a scientific study of human society - a study which came to be known as Social Darwinism. Basing his concepts of evolution not on Darwin, in fact, but on those expounded by the 18th century French naturalist Jean Baptiste de Lamarck (the theory that organisms developed parts that were better adapted to its needs) he argued that human behaviour was socially determined, and that individual characteristics developed through the process of evolution.

xxxxxHowever, unlike Darwin’s idea of natural selection (which was open-ended), Spencer saw evolution as synonymous with progress. Human nature was “the aggregate of man’s instincts and sentiments” and, given a long process of evolution, would produce “the perfect man in the perfect society” - the ultimate state of perfection. This being the case, the process which ensured the survival of the fittest, - a term coined by Spencer himself in 1864 - must be allowed to take its course without undue interference from persons or the state.

xxxxxHowever, unlike Darwin’s idea of natural selection (which was open-ended), Spencer saw evolution as synonymous with progress. Human nature was “the aggregate of man’s instincts and sentiments” and, given a long process of evolution, would produce “the perfect man in the perfect society” - the ultimate state of perfection. This being the case, the process which ensured the survival of the fittest, - a term coined by Spencer himself in 1864 - must be allowed to take its course without undue interference from persons or the state.

xxxxxAs a consequence Spencer favoured a policy of laissez-faire, and advocated the abolition of poor laws, national education, acts of charity, and any other means being provided to support the less able. This would ensure that weak societies would be eliminated, strong ones would survive, and the perfect society would eventually be achieved.

xxxxxThe major volumes in his System of Synthetic Philosophy, were the opening work First Principles, Principles of Biology (1864-67), Principles of Sociology, begun in 1876, and Principles of Sociology, completed in 1893. Other works included Essays on Education in 1861, The Study of Sociology of 1873, and Essays: Scientific, Political and Speculative. One of his best known works, Man versus the State, produced in 1884, was a powerful attack upon the government of the day (led by Gladstone at the time), denouncing welfare reforms and asserting that legislation limited the rights of the individual and could only bring “misery and compulsion”.

xxxxxSpencer’s influence was at its height throughout the 1870s and 1880s. Apart from his theory of social evolution, his works contributed to developments in biology, psychology, anthropology and sociology at university level. At a time of social and political flux, his championship of individualism and his timely warning against the ever increasing powers of the state proved popular themes. However, there were inconsistencies and unanswered questions in his philosophy, and towards the end of his career he lost some public support because of his opposition to the Boer War, seen by him as an interference in the evolutionary process.

xxxxxIncidentally, Spencer’s contention that persons and races are subject to the laws of natural selection gave rise to the idea of a master race. The German fuhrer Adolf Hitler, seizing power in the 1930s, regarded other races as inferior to what he called the “Aryan peoples”. During the Second World War (1939-1945) he set out deliberately to destroy the Jewish population in Europe. ……

xxxxx…… Spencer did not enjoy good health, and for much of his life could only work a few hours each day. He was a very private person, but he had a number of close friends. These included Thomas Huxley (Darwin’s “bulldog”) and the writer Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot), with whom he was romantically linked for a time. ……

xxxxx…… ThexAmerican academic William Graham Sumner (1840-1910), one time professor at Yale University, was strongly influenced by Spencer in the 1870s. As a Social Darwinist he defended laissez-faire and was a sharp critic of imperialism. He published The Survival of the Fittest in 1884.

x

x xxxxItxwas during the 1870s that the English archaeologist William Pengelly (1812-1894), (illustrated) sponsored by the Royal Geological Society, carried out a scientific investigation of Kents Cavern, a limestone cave near Torquay in Devon, England. He and his team recovered some 8,000 artefacts - mainly flint tools - and estimated, from stalagmite growth rates, that they were over half a million years old. These findings were among the first to refute the calculation - and similar deductions - that the world was created the night before the 23rd October 4004 BC, made by the Primate of all Ireland, James Ussher (1581-1656), in 1654. He based his date on a verse in the New Testament (2 Peter), that one day was with the Lord as a thousand years, and “a thousand years as one day”.

xxxxItxwas during the 1870s that the English archaeologist William Pengelly (1812-1894), (illustrated) sponsored by the Royal Geological Society, carried out a scientific investigation of Kents Cavern, a limestone cave near Torquay in Devon, England. He and his team recovered some 8,000 artefacts - mainly flint tools - and estimated, from stalagmite growth rates, that they were over half a million years old. These findings were among the first to refute the calculation - and similar deductions - that the world was created the night before the 23rd October 4004 BC, made by the Primate of all Ireland, James Ussher (1581-1656), in 1654. He based his date on a verse in the New Testament (2 Peter), that one day was with the Lord as a thousand years, and “a thousand years as one day”.

xxxxxAs we have seen, The Origin of Species, published in 1859 (Va) by the English naturalist Charles Darwin, aroused bitter controversy, especially among Church leaders. His theory that life on earth had evolved over millions of years, a thesis developed during his five-

xxxxxAs we have seen, The Origin of Species, published in 1859 (Va) by the English naturalist Charles Darwin, aroused bitter controversy, especially among Church leaders. His theory that life on earth had evolved over millions of years, a thesis developed during his five- xxxxxThe Origin of Species, “the book that shook the world”, had touched on, albeit briefly, the sensitive issue of man’s part in this theory of evolution, and this had been the cause of much heated debate. In 1871, however, following further research, Darwin added fuel to the controversy with the publication of The Descent of Man, a work in which he attempted to consider more fully “the origin of man and his history” and the theory of “selection in relation to sex”. He argued that man, like other species, had descended from some pre-

xxxxxThe Origin of Species, “the book that shook the world”, had touched on, albeit briefly, the sensitive issue of man’s part in this theory of evolution, and this had been the cause of much heated debate. In 1871, however, following further research, Darwin added fuel to the controversy with the publication of The Descent of Man, a work in which he attempted to consider more fully “the origin of man and his history” and the theory of “selection in relation to sex”. He argued that man, like other species, had descended from some pre- xxxxxLikewise, the diverse make-

xxxxxLikewise, the diverse make- xxxxxThe second half of the book is an expansion of his theory of sexual selection, described by Darwin as the effects of the “struggle between individuals of one sex, generally males, for the possession of the other”, -

xxxxxThe second half of the book is an expansion of his theory of sexual selection, described by Darwin as the effects of the “struggle between individuals of one sex, generally males, for the possession of the other”, - xxxxxFollowing on from his Origin of Species, The Descent of Man caught the public imagination and re-

xxxxxFollowing on from his Origin of Species, The Descent of Man caught the public imagination and re-

xxxxxA scientist who gave a great deal of support to Darwin’s theory, though not to his ideas on natural selection, was the German zoologist and philosopher Ernst Haeckel (1834-

xxxxxA scientist who gave a great deal of support to Darwin’s theory, though not to his ideas on natural selection, was the German zoologist and philosopher Ernst Haeckel (1834- f science dealing with the inter-

f science dealing with the inter-

xxxxxA man whose reputation at this time rivalled that of Charles Darwin, was the English philosopher of biological and social evolution Herbert Spencer (1820-

xxxxxA man whose reputation at this time rivalled that of Charles Darwin, was the English philosopher of biological and social evolution Herbert Spencer (1820- xxxxxHowever, unlike Darwin’s idea of natural selection (which was open-

xxxxxHowever, unlike Darwin’s idea of natural selection (which was open-

x

x xxxxItxwas during the 1870s that the English archaeologist William Pengelly (1812-

xxxxItxwas during the 1870s that the English archaeologist William Pengelly (1812-