xxxxxThe French painter Jacques-Louis David, the leading and greatest exponent of neo-classicism, was a politically motivated man who, directly or indirectly, used his artistic talent almost exclusively in the service of his country. A totally committed republican, he narrowly escaped the guillotine in 1794, and then went on to devote much of his time and energy to boosting the public image of his “hero” Napoleon. For some thirty years this ardent, volatile patriot was a force in the land, be it as a politician on the stage or a propagandist on canvas. Indeed, such was the impact of his work, that the noble virtues attributed to ancient Rome and Greece, captured within his austere, classical style, came to represent the ideals of both the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Empire. (The illustration is a self-portrait).

xxxxxThe French painter Jacques-Louis David, the leading and greatest exponent of neo-classicism, was a politically motivated man who, directly or indirectly, used his artistic talent almost exclusively in the service of his country. A totally committed republican, he narrowly escaped the guillotine in 1794, and then went on to devote much of his time and energy to boosting the public image of his “hero” Napoleon. For some thirty years this ardent, volatile patriot was a force in the land, be it as a politician on the stage or a propagandist on canvas. Indeed, such was the impact of his work, that the noble virtues attributed to ancient Rome and Greece, captured within his austere, classical style, came to represent the ideals of both the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Empire. (The illustration is a self-portrait).

xxxxxDavid was born into a well-to-do middle class family in Paris, and was first given art lessons by the renowned rococo artist François Boucher, a distant cousin. Hexthen received instruction from the Neo-Classicist Joseph-Marie Vien (1716-1809) and, after four attempts - during which, deeply depressed by his failure, he threatened to commit suicide - he won the coveted Prix de Rome in 1774. Before setting off for Italy, he confidently declared that the art of antiquity would not “seduce” him, but once settled in the Eternal City he was completely bowled over and won over by the wealth and pure beauty of classical sculpture, his conversion influenced not a little by a visit to the excavations being carried out in Pompeii and Herculaneum at that time. He spent five years drawing Roman statutory and friezes, studying the Renaissance masters, and showing a particular interest in the classically inspired work of the 17th-century French painter Nicolas Poussin.

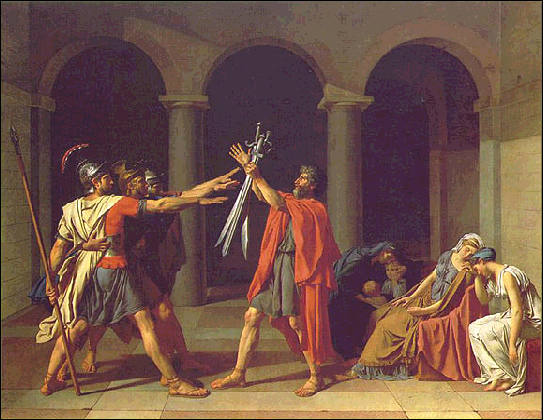

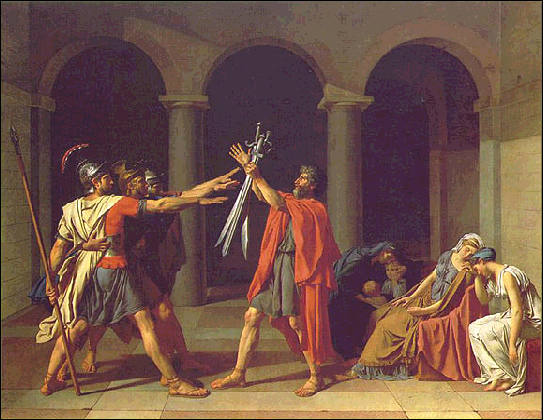

xxxxxHis first major work in this strict, classical ideal was The Oath of the Horatii (illustrated), an heroic historical scene in which three brothers nobly pledge their lives to the defence of Rome, their native city. In this painting, completed in 1784, David consciously set out to demonstrate the hallmarks of his new neo-classical style. The principal action was confined to a ribbon area (as though part of a frieze), the outlines were clean cut, colours were subdued, emotion was restrained - save for the occasional statue-like gesture -, and the lighting was clear and direct. Exhibited in Paris in 1785 it was a sensation, and made his reputation overnight. It was not only a reaction against rococo frivolity and depravity (and, by implication, a condemnation of the ancien régime it served), but also a call to patriotism and a return to the noble standards of courage and stoicism associated with the ancient republic of Rome. He followed this with a number of works in similar vein, including, two years later, The Death of Socrates, another lesson in duty and self sacrifice from an heroic past.

xxxxxHis first major work in this strict, classical ideal was The Oath of the Horatii (illustrated), an heroic historical scene in which three brothers nobly pledge their lives to the defence of Rome, their native city. In this painting, completed in 1784, David consciously set out to demonstrate the hallmarks of his new neo-classical style. The principal action was confined to a ribbon area (as though part of a frieze), the outlines were clean cut, colours were subdued, emotion was restrained - save for the occasional statue-like gesture -, and the lighting was clear and direct. Exhibited in Paris in 1785 it was a sensation, and made his reputation overnight. It was not only a reaction against rococo frivolity and depravity (and, by implication, a condemnation of the ancien régime it served), but also a call to patriotism and a return to the noble standards of courage and stoicism associated with the ancient republic of Rome. He followed this with a number of works in similar vein, including, two years later, The Death of Socrates, another lesson in duty and self sacrifice from an heroic past.

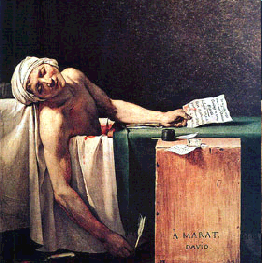

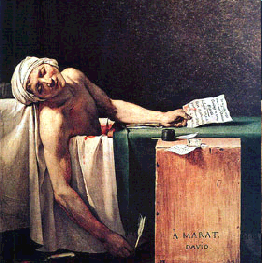

XxxxxHe returned to France in 1780, and in 1789 became a zealous, hyper-active supporter of the French Revolution. In 1792 he represented Paris in the National Convention and, as a member of the extremist group led by Robespierre, he voted in favour of the execution of the king. In 1793 he joined the art commission, where he virtually took control of the nation’s artistic affairs and public festivals, and came to be known as “The Robespierre of the Brush”. To this period belongs a number of historical works, including his famous Death of Marat (illustrated below), painted in 1793, the same year that Charlotte Corday murdered the “friend of the people” in his bath. The scene he produced, stripped bare of all but the essentials, captures all the tragedy of a sparse, classical drama, but the figure of his friend Marat is sympathetically portrayed.

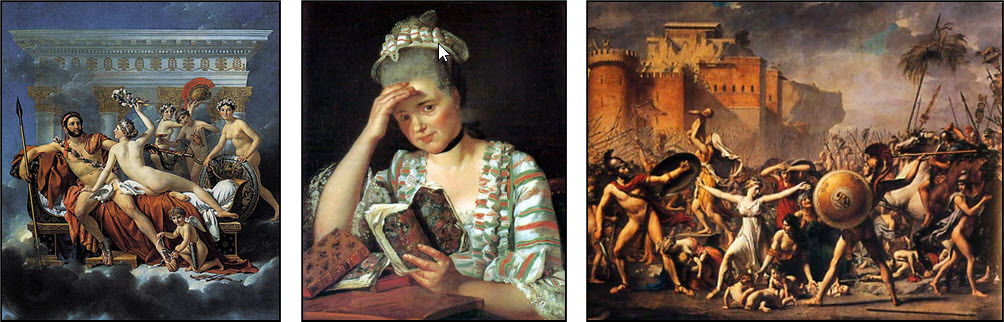

xxxxxFollowing the execution of his ally Robespierre in July 1794, David’s life was in danger. He was twice imprisoned and narrowly escaped the guillotine himself. He regained his freedom by his repudiation of Robespierre, and by the efforts of his former wife Charlotte Pecoul (whom he later remarried). In gratitude to her loyalty he dedicated his next major work to her in 1799. Entitled Les Sabines (The Sabine Women) (illustrated below), this giant canvass depicted a Roman legend in which the Sabine women intervened and pleaded for peace in the midst of a battle between their Roman husbands and the Sabine men who had come to rescue them. Brilliantly executed in a posed, classical setting, it was seen by many, intended or not, as a plea for conciliation in the civil conflict which followed the French Revolution.

xxxxxBut this huge, dramatic work had an additional effect. It was seen and much admired by Napoleon, who rightly judged that such talent could be used to boost his own public image. As a consequence, David found himself back in government service, this time as the official painter to the First Consul and, later, the Emperor. He did not accompany Napoleon on his campaigns - this was left to his pupil Antoine-Jean Gros - but, nonetheless, he did his master proud. Works of this period included his huge coronation scene, completed in 1807, Napoleon crossing the Alps (illustrated), “calm on a fiery steed” (though because of the terrain he actually crossed the Alps on a mule!), and his famous Napoleon in his Study, a work which, for all its good intentions, reveals the great man as a portly mortal.

xxxxxAnd it was during this period that, as an accomplished portrait artist, he produced one of his finest works, Madame de Récamier, a young Paris beauty (here illustrated). The work was never fully completed due, we are told to a dispute over the colour of her hair. It was naturally black, but it appears that David painted it brown to accord with his general colour scheme! This and his other portraits - which included one of the French chemist Antoine Lavoisier and his wife - are considered by many to be amongst his best work. It must be said however, that his neo-classical paintings did tend to be statuesque and stilted at times, lacking the emotional content needed to breathe life into the figures.

xxxxxAnd it was during this period that, as an accomplished portrait artist, he produced one of his finest works, Madame de Récamier, a young Paris beauty (here illustrated). The work was never fully completed due, we are told to a dispute over the colour of her hair. It was naturally black, but it appears that David painted it brown to accord with his general colour scheme! This and his other portraits - which included one of the French chemist Antoine Lavoisier and his wife - are considered by many to be amongst his best work. It must be said however, that his neo-classical paintings did tend to be statuesque and stilted at times, lacking the emotional content needed to breathe life into the figures.

xxxxxFollowing Napoleon’s exile after the Battle of Waterloo, David was himself required to leave France. In 1816 he went to live in Belgium, and he remained there until his death in Brussels some ten years later. In these last years he produced some works based on mythological subjects, several of which were of an erotic nature, such as his Mars Disarmed by Venus - illustrated below together with the portrait of Madame François Buron and The Intervention of the Sabine Women.

xxxxxDavid’s influence as a neo-classical artist was immense. The pure classical style that he introduced brought a reversal in French taste, putting an end to the rococo style with its superficiality and eroticism. For over three decades he was responsible for the training of hundreds of young artists from all over France. Among these were masters-in-the-making, like Antoine-Jean Gros, François Gérard, and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. These dominated French painting throughout the first half of the 19th century. And his form of neo-classicism had a marked impact outside of France, where it was adopted especially in Flemish and Danish painting. But, as we shall see, these lofty ideals, based on an art form of ancient times, were eventually to founder upon their own rigid format, leaving the way open to the emotion and imagination of the Romantic Movement.

xxxxxIncidentally, David went all out to evoke public sympathy for the death of his friend Jean Paul Marat - a man feared by many. It is hardly surprising, in fact, that his painting of him lying dead in his bath - where he often sat to ease a severe skin disease - came to be known as the "pietà of the Revolution". In order to heighten the sense of martyrdom, David modelled Marat’s pose on the pietà produced by Michelangelo for St. Peter’s basilica. His head is gently inclined and one arm hangs limply down by his side, almost identical to the position of Christ’s right arm. And David also skilfully orchestrated Marat’s lying-in-state, intensifying dramatic effect by including his bath and the old packing case he used as a desk!

xxxxxIncidentally, David went all out to evoke public sympathy for the death of his friend Jean Paul Marat - a man feared by many. It is hardly surprising, in fact, that his painting of him lying dead in his bath - where he often sat to ease a severe skin disease - came to be known as the "pietà of the Revolution". In order to heighten the sense of martyrdom, David modelled Marat’s pose on the pietà produced by Michelangelo for St. Peter’s basilica. His head is gently inclined and one arm hangs limply down by his side, almost identical to the position of Christ’s right arm. And David also skilfully orchestrated Marat’s lying-in-state, intensifying dramatic effect by including his bath and the old packing case he used as a desk!

xxxxxThe French painter Jacques-

xxxxxThe French painter Jacques- xxxxxHis first major work in this strict, classical ideal was The Oath of the Horatii (illustrated), an heroic historical scene in which three brothers nobly pledge their lives to the defence of Rome, their native city. In this painting, completed in 1784, David consciously set out to demonstrate the hallmarks of his new neo-

xxxxxHis first major work in this strict, classical ideal was The Oath of the Horatii (illustrated), an heroic historical scene in which three brothers nobly pledge their lives to the defence of Rome, their native city. In this painting, completed in 1784, David consciously set out to demonstrate the hallmarks of his new neo-

xxxxxAnd it was during this period that, as an accomplished portrait artist, he produced one of his finest works, Madame de Récamier, a young Paris beauty (here illustrated). The work was never fully completed due, we are told to a dispute over the colour of her hair. It was naturally black, but it appears that David painted it brown to accord with his general colour scheme! This and his other portraits -

xxxxxAnd it was during this period that, as an accomplished portrait artist, he produced one of his finest works, Madame de Récamier, a young Paris beauty (here illustrated). The work was never fully completed due, we are told to a dispute over the colour of her hair. It was naturally black, but it appears that David painted it brown to accord with his general colour scheme! This and his other portraits -

xxxxxIncidentally, David went all out to evoke public sympathy for the death of his friend Jean Paul Marat -

xxxxxIncidentally, David went all out to evoke public sympathy for the death of his friend Jean Paul Marat -