xxxxxFrom an early

age Leopold II of Belgium was convinced that a country’s path to

greatness lay in the possession of colonial territories. Unable to

convince his government of this, he decided to go it alone. He

formed the International Congo Society in 1879, and then

commissioned the explorer Henry Morton Stanley to return to

central Africa in order to gain rights over productive areas and

the exclusive control of the rubber and ivory trades. This

achieved, he obtained the support of the Berlin Conference

(convened in 1884 to regulate the colonisation of Africa) and

established the Congo Free State, a vast area, 75 times larger than Belgium, in 1885. He had always made it

clear that his intention was to end the Arab slave trade in that

area, and bring the benefits of civilisation to the native

population, but once in power he exploited the land for its

natural products and mineral wealth -

LEOPOLD II OF BELGIUM 1835 -

Acknowledgements

Leopold II:

c1866, artist unknown – Musée de la Dynastie, Brussels, Belgium. Map (Congo): licensed under Creative Commons –

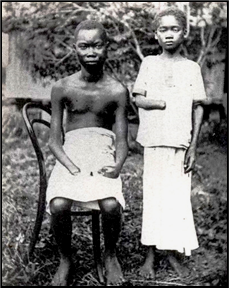

https://shsaplit.wikispaces.com/poisonwood_review. Mutilation: this photograph and many of a similar nature were

taken by two English missionaries, John Harris (1874-

xxxxxLeopold II of Belgium succeeded his father to the

throne in 1865. A strong-

xxxxxLeopold II of Belgium succeeded his father to the

throne in 1865. A strong-

xxxxxOne area

which still remained open for his purpose was the Congo Basin in

the centre of the African continent. Because of its jungle terrain

and the dangers and diseases that went with it, this vast area had

attracted few outside visitors. As we have seen, the Portuguese

navigator Diogo Cao had reached the estuary of the Congo River in

1482 (E4) and,

as a result, missionaries had visited the interior in 1490, and

treaties had been made, though nothing had come of it. With

this area in mind, in 1879 Leopold set up the so- further

in order to establish friendly relations with the tribal chiefs

and set up trading stations. Privately,

he was charged with gaining sovereign rights over productive

areas, and exclusive control of the ivory and rubber trade. Over

the next five years Stanley founded a number of settlements along

the middle Congo, including Leopoldville, and made over 450

treaties with local chiefs, securing trading rights and ownership

over vast regions on the south bank of the River Congo. By his

return in 1884, Leopold was virtual master of what was to become

the

further

in order to establish friendly relations with the tribal chiefs

and set up trading stations. Privately,

he was charged with gaining sovereign rights over productive

areas, and exclusive control of the ivory and rubber trade. Over

the next five years Stanley founded a number of settlements along

the middle Congo, including Leopoldville, and made over 450

treaties with local chiefs, securing trading rights and ownership

over vast regions on the south bank of the River Congo. By his

return in 1884, Leopold was virtual master of what was to become

the

xxxxxAll Leopold

required now was international recognition of his claim to this

vast territory. As we have seen, his opportunity to achieve that

came later in 1884

at the Berlin Conference, convened in the November with the

specific task of regulating European colonisation and trade within

Africa. Organised, as we have seen, by the German chancellor Otto

von Bismarck, it was held amid growing international concern about

a new phase of colonial activity within the continent. In addition

to Leopold’s own ambitions in central Africa -

xxxxxBut not surprisingly for that day and age, the light

of civilisation -

xxxxxBut not surprisingly for that day and age, the light

of civilisation -

xxxxxAnd this

legalised robbery was enforced by violence. The exploitation of

the land and its products was accompanied by a harsh, brutal

regime, carried out by the concessionary companies and Leopold’s Force Publique, a private army that

terrorised the native population. The state became a vast labour

camp in which flogging, torture, mass killing and widespread

mutilation were routine. And the  harvesting

of wild rubber became a particularly gruesome industry following

the invention of the pneumatic tyre in the mid-

harvesting

of wild rubber became a particularly gruesome industry following

the invention of the pneumatic tyre in the mid-

xxxxxAs early as

1888 news of these atrocities began to leak out. In that year

Cardinal Charles Lavigerie, a French missionary, gave a sermon in

Paris which shocked his audience by its gory account of the Congo

slave trade. This prompted Leopold to convene an international

conference in Brussels in 1889-

xxxxxMatters came to a head in 1900 when a native uprising

was mercilessly crushed and details of flogging, mutilation and

murder were circulated. Leopoldxattempted

to silence the press, but the following year a former shipping

clerk named Edmund Dene Morel (1873-

xxxxxMatters came to a head in 1900 when a native uprising

was mercilessly crushed and details of flogging, mutilation and

murder were circulated. Leopoldxattempted

to silence the press, but the following year a former shipping

clerk named Edmund Dene Morel (1873-

xxxxxApart from

his infamous venture into colonialism, Leopold is remembered today

for the palatial public buildings he erected in Brussels, Ostend

and Antwerp -

x

x xxxxIncidentally, in 1904 Morel

and Casement formed the Congo Reform

Association in Britain to fight for much-

xxxxIncidentally, in 1904 Morel

and Casement formed the Congo Reform

Association in Britain to fight for much-

xxxxx…… Roger Casement, the British consular official who, in 1904, drew up the harrowing report on conditions in the Congo Free State, was awarded a knighthood in 1911 and hanged as a traitor five years later. An ardent Irish nationalist, when the First World War broke out in 1914 he went to Germany in the hope of raising a force of Irish war prisoners to fight against the British. His mission was unsuccessful, but when he returned to Ireland in a German submarine he was captured on landing. He was taken to London, tried for high treason, and hanged.

Vc-

Including:

The Congo

Free State