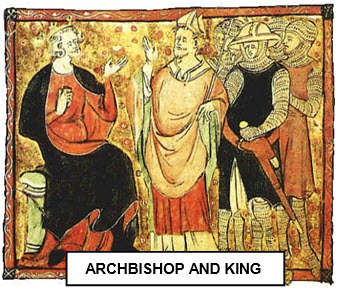

THE CLARENDON CONSTITUTIONS 1164 (H2)

xxxxxThese resolutions, agreed by a council convened by the king, were drawn up to limit the secular powers of the clergy. During the reign of Stephen, the church courts had virtually become a law unto themselves, well known for the leniency of their sentences. Thus the sixteen articles passed at Clarendon in 1164 cut back on clerical privileges and drastically reduced the authority of the church courts. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, reluctantly agreed to these restrictions, but was particularly opposed to Clause 3, which stated that any priest found guilty of a serious crime would receive his punishment from a secular and not a church court. Inside of a year Becket took a stand, withdrew his support for the king, and appealed directly to the Pope for help. This put an end to his friendship with Henry, and, fearing the worst, he fled in disguise, taking refuge in France. As we shall see, when he did eventually return, six years later in 1170, it was to be a matter of days before he was murdered on the altar steps of his own cathedral at Canterbury, much to the horror of Christendom.

xxxxxThese constitutions, or resolutions, agreed by a council convened by the King at Clarendon in Wiltshire, were specifically drawn up to limit the secular powers of the clergy. During the troubled reign of his predecessor, Stephen, the church courts had virtually had it all their own way. Given greater legal status by the up-

xxxxxThese constitutions, or resolutions, agreed by a council convened by the King at Clarendon in Wiltshire, were specifically drawn up to limit the secular powers of the clergy. During the troubled reign of his predecessor, Stephen, the church courts had virtually had it all their own way. Given greater legal status by the up-

xxxxxThere were sixteen articles in all. Basically, they gave the monarch the right to punish "criminous clerks" (priests who had committed a crime) after they had been tried by a church court; they forbade the Church to make appeals to Rome or attempt to excommunicate officials of the crown; and they entitled the king to any revenue from vacant sees or monasteries. In short, they aimed at cutting back on clerical privileges, and drastically reducing the power of the church councils, long known for the leniency of their sentences.

xxxxxAt first the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket -

xxxxxAt first the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket -

xxxxxIt was to be six years before Becket was to return as Archbishop, and inside the month of his return, December 1170, he was to be killed on the altar steps of Canterbury Cathedral. Europe was shocked, Becket became a martyr, his tomb became a shrine, and Henry, proclaiming his innocence, was obliged to do penance. Such were the fruits of the Clarendon Constitutions.

Acknowledgement

Archbishop and King: 14th century manuscript illustration, artist unknown, contained in Liber Legum Antiquorum Regum – British Library, London.

H2-