xxxxxThe furniture designer and cabinetmaker Thomas Chippendale was a Yorkshireman. He came to London in 1749, and very soon gained a reputation as a brilliant craftsman. This reputation was greatly enhanced in 1754 with the publication of his The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker's Director. This was a catalogue of 160 pieces of domestic furniture in the ornate but tasteful style known as rococo. Most of the designs illustrated the more restrained, English interpretation of this style, but there were also patterns to meet the taste for the Gothic, or the current liking for all things Chinese (Chinoiserie).These designs were widely copied in Britain -

THOMAS CHIPPENDALE 1718 -

Acknowledgement

Chippendale: detail, after the English painter Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-

G2-

xxxxxThe English furniture designer and cabinetmaker Thomas Chippendale was born in Otley, Yorkshire and, perhaps not surprisingly, was the son of a carpenter. He came to work in London as a young man, and in 1753 set up his workshops and showrooms in St. Martin's Lane. Here, his own particular  style of craftsmanship was soon in great demand, combining as it did strength of structure with the elaborate but tasteful decoration associated with the rococo style.

style of craftsmanship was soon in great demand, combining as it did strength of structure with the elaborate but tasteful decoration associated with the rococo style.

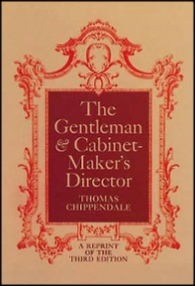

xxxxxIn 1754, calling upon his wealth of experience in furniture design, he published his The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker's Director, a trade catalogue of domestic furniture which was enthusiastically received both by those in the trade and the wealthy members of the gentry and merchant classes. It contained 160 engravings of various rococo designs, many illustrating the more restrained, English interpretation of this highly decorative style. This "modern" taste, as it was termed, was certainly not without decoration, but for the most part Chippendale worked in mahogany in order to exploit the magnificence of the grain, and this tended to prohibit inlay work (or ormolu), much in vogue on the continent during this period.

xxxxxBut this collection of engravings also contained rococo designs in Gothic and Chinese taste. "Gothic Chippendale", for example, incorporated pointed arches and imposing pediments, whilst the Chinese version was aimed at meeting the needs of the market. Chinoiserie was all the rage at this time, especially in pottery and textiles, and the introduction of Chinese motifs into these designs, and/or a coating of oriental-

xxxxxBut this collection of engravings also contained rococo designs in Gothic and Chinese taste. "Gothic Chippendale", for example, incorporated pointed arches and imposing pediments, whilst the Chinese version was aimed at meeting the needs of the market. Chinoiserie was all the rage at this time, especially in pottery and textiles, and the introduction of Chinese motifs into these designs, and/or a coating of oriental-

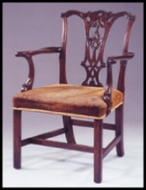

xxxxxPerhaps out of all the grand pieces of furniture that Chippendale produced, he is best remembered for his improvement in the design of the chair. It was he who replaced the solid, heavy back-

xxxxxPerhaps out of all the grand pieces of furniture that Chippendale produced, he is best remembered for his improvement in the design of the chair. It was he who replaced the solid, heavy back-

xxxxxChippendale was probably not the greatest of all cabinetmakers, but he knew a good design when he saw one, and his Director gave an enormous boost to his career. Orders came pouring in, and his workshops could hardly cope. Among those who visited his showroom were the writer Oliver Goldsmith and the artists William Hogarth and Sir Joshua Reynolds. Indeed, his work and designs so dominated the middle years of the century that his name became virtually synonymous with English furniture in general. Nor was his success confined to Britain. His furniture patterns were copied or imitated extensively on the continent and in the American colonies.

xxxxxBut, as we shall see (1762 G3a), it was in his later years, when he worked in collaboration with the English architect Robert Adam and adopted the new Neo-

xxxxxIncidentally, little is known of Chippendale's private life, save that he married twice and had eleven children. It would seem, however, that he had no doubts about the quality of his own pieces of furniture. Speaking of these, he is alleged to have said: "which, if I may speak without vanity, are the best I have ever seen".

Including:

Jean François

Oeben

xxxxxAnother celebrated furniture maker of this period was the German Jean François Oeben (1715-

xxxxxOne of the most celebrated cabinetmakers of this period was the German Jean François Oeben (1715-

xxxxxOne of the most celebrated cabinetmakers of this period was the German Jean François Oeben (1715-

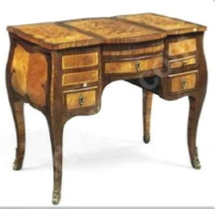

xxxxxAn exponent of the exuberant rococo style, his furniture was full of curves and bulging fronts, and covered with an abundance of surface decoration. This included gilding, motifs depicting flowers and animals, and a great deal of highly intricate and elaborate marquetry (inlaid work in wood, illustrated above), a technique which he developed to perfection. In addition, he also gained a wide reputation for his ingenious locks and mechanical devices, many used to conceal secret drawers and compartments in his pieces. In 1761 he began work on his masterpiece, a large desk specially designed for Louis XV and known as the Bureau du Roi. It was not quite finished at the time of his death, and was completed by his young apprentice Jean Henri Riesener. It is now in the Louvre.

xxxxxAn exponent of the exuberant rococo style, his furniture was full of curves and bulging fronts, and covered with an abundance of surface decoration. This included gilding, motifs depicting flowers and animals, and a great deal of highly intricate and elaborate marquetry (inlaid work in wood, illustrated above), a technique which he developed to perfection. In addition, he also gained a wide reputation for his ingenious locks and mechanical devices, many used to conceal secret drawers and compartments in his pieces. In 1761 he began work on his masterpiece, a large desk specially designed for Louis XV and known as the Bureau du Roi. It was not quite finished at the time of his death, and was completed by his young apprentice Jean Henri Riesener. It is now in the Louvre.

xxxxxIncidentally, itxwas around this time that the French Martin brothers, Guillaume, Robert, Julien and Étienne-