xxxxxBy the time the Europeans

arrived in North America, the Cherokee tribe was firmly settled in

the Carolinas, Tennessee and parts of Georgia and Alabama. The

Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto passed through their land in 1539,

and it was in Georgia in 1733 that the English philanthropist James

Oglethorpe made the first European settlement. The Cherokee

supported the Crown during the American War of Independence and, as

a result, lost much of their territory at the end of the conflict.

When gold was discovered in Georgia in 1827, demand grew for the

removal of the native Indians. In 1830 Congress passed the Indian

Removal Act by which native Indians could to be forcibly ejected

from their homelands. The final blow came in 1835 when some senior

Cherokees sold their land to the government. In 1838 U.S. forces arrived in Georgia and forced-

THE CHEROKEE AND THE TRAIL OF

TEARS 1838 -

Acknowledgements

Cherokee: Cherokee Indian

Sitemap, artist unknown. Map (USA):

licensed under Creative Commons – https://asd-

xxxxxThe Cherokee

Indians are thought to have originated in present day Texas and the

northern part of Mexico, and to have migrated to the area of the

Great Lakes in prehistoric times. Here they came in conflict with

the Delaware and Iroquois tribes and, getting the worst of it, moved

to the south east, settling in what is now the Carolinas, Tennessee,

and the northern regions of Georgia and Alabama. Within a

comparatively few years they had become the most powerful and

advanced tribe in that region. The Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto

passed through their territory in 1539 -

xxxxxThe Cherokee

Indians are thought to have originated in present day Texas and the

northern part of Mexico, and to have migrated to the area of the

Great Lakes in prehistoric times. Here they came in conflict with

the Delaware and Iroquois tribes and, getting the worst of it, moved

to the south east, settling in what is now the Carolinas, Tennessee,

and the northern regions of Georgia and Alabama. Within a

comparatively few years they had become the most powerful and

advanced tribe in that region. The Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto

passed through their territory in 1539 -

xxxxxIn the struggle between the

British and French for control of North America, the Cherokee had

tended to side with the British and, during the American War of

Independence they openly supported the forces of the Crown. This

proved their undoing. After the success of the American rebels, they

were obliged to agree to a series of humiliating treaties by which

they lost vast areas of their land in the Carolinas. Some of the

tribe, about 3,000, sensing trouble ahead, moved west of the

Mississippi, but the majority stayed on, developing their farming

and cattle ranching, and maintaining a well- society.

In 1827 the tribe went so far as to establish the Cherokee Nation,

with a system of representative government based closely on the US

model. But by then its fate was virtually sealed. Valuable gold

deposits had been discovered in the mountains to the north, and as

early as 1819 Georgia had asked the U.S. government to expel the

Cherokee from the state. This appeal had failed, but in 1828 Georgia

took the law into its own hands and laid claim to the tribal lands.

This was judged as illegal by the U.S. Supreme Court, sitting in

1832, but by then President Andrew Jackson had signed the

society.

In 1827 the tribe went so far as to establish the Cherokee Nation,

with a system of representative government based closely on the US

model. But by then its fate was virtually sealed. Valuable gold

deposits had been discovered in the mountains to the north, and as

early as 1819 Georgia had asked the U.S. government to expel the

Cherokee from the state. This appeal had failed, but in 1828 Georgia

took the law into its own hands and laid claim to the tribal lands.

This was judged as illegal by the U.S. Supreme Court, sitting in

1832, but by then President Andrew Jackson had signed the

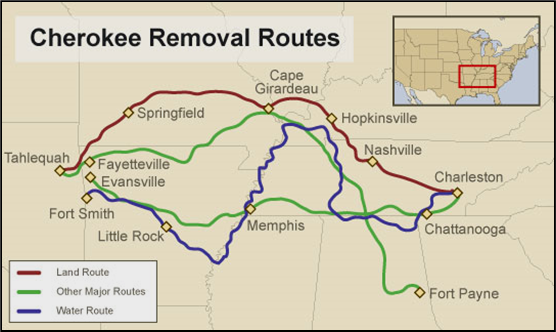

xxxxxThexfinal

blow came in 1835 when, by the Treaty of

New Echota, about 500 prominent Cherokee

were cajoled into selling their ancestral home for five million

dollars, and moving to the so-

xxxxxIn the weeks that followed, only a few hundred Cherokee

and Creek Indians managed to escape and settle on land in the North

Carolina mountains -

xxxxxIn the weeks that followed, only a few hundred Cherokee

and Creek Indians managed to escape and settle on land in the North

Carolina mountains -

xxxxxNor did matters improve much after being “settled” in the Indian Territory. Here, having joined up with the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole (becoming known as the Five Civilized Tribes), they come up against thousands of tribesmen from the north, many of whom had sadly and reluctantly accepted their removal to less productive land. Feuds broke out across the region as each tribe attempted to establish its own territory. Then, with the coming of the American Civil War in 1861, the Five Tribes supported the South and came out the losers. After the conflict, tribal ownership of land was abolished, and in the late 1880s the government of the Cherokee Nation was dissolved, its people becoming U.S. citizens when Oklahoma was made a state in 1907. From then on white settlers began to pour into the region.

xxxxxIncidentally, it was during

the Trail of Tears (or, literally, “The Trail where they cried”)

that the legend of the Cherokee Rose was born. It is said that,

after the chiefs had prayed for a sign to bring comfort to all the

mothers and to give them the strength to care for their children, a

beautiful white rose sprang up wherever a mother’s tear touched the

ground. The white was seen as the colour of the tear; the bright

gold centre as the gold which had been stolen from their land; and

the seven petals as representing the seven Cherokee clans. We are

told that this rose -

xxxxxIncidentally, it was during

the Trail of Tears (or, literally, “The Trail where they cried”)

that the legend of the Cherokee Rose was born. It is said that,

after the chiefs had prayed for a sign to bring comfort to all the

mothers and to give them the strength to care for their children, a

beautiful white rose sprang up wherever a mother’s tear touched the

ground. The white was seen as the colour of the tear; the bright

gold centre as the gold which had been stolen from their land; and

the seven petals as representing the seven Cherokee clans. We are

told that this rose -

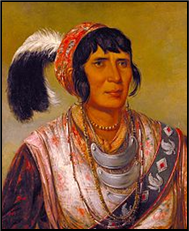

xxxxxThe man who served the

Cherokee Indians well during their troubled times was their tribal

leader John Ross

(1790-

xxxxxOver the next ten years he struggled relentlessly to keep his tribe in their ancestral lands, using every means short of war. He sent petitions to President Andrew Jackson, and in the early 1830s went to Washington to plead his case in person. His efforts were of no avail. When eviction eventually came in 1838, he led his people in the “trail of tears”, sharing in their ordeal and overseeing their resettlement in the Indian Territory. And it was there that he helped write a constitution for the United Cherokee Nation, and was chosen as chief when the new government was formed.

Including:

John Ross,The Second and

Third Seminole Wars, and

George Catlin

xxxxxAnother tribe which

resisted eviction was the Seminole in Florida. As we have seen, they

had already battled with government forces in 1817 to keep hold of

their homeland. In the Second Seminole War,

beginning in 1835, they again put up a good fight, but with the

capture of their able leader Osceola in 1837 they were forced to

surrender in 1842. And some resistance was shown among tribes north

of the Ohio River. In 1832, for example, the Sauk leader Black Hawk

took on the government in the so-

xxxxxOn his return home in 1838

he assembled his paintings -

xxxxxParamount among Catlin’s

writings was his Manners, Customs and Conditions

of the North American Indian, a two-

xxxxxA tribe which was even more determined than the Cherokee to hold on to their native lands were the Seminole in Florida. As we have seen, they had already fought one war with the American government in 1817, when federal forces had attempted to drive them out of the peninsula, then owned by the Spanish. This struggle was resumed in 1835 when the American government, on the strength of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, attempted once again to evict them and, this time, to drive them to those designated native areas in the far West.

xxxxxBut,xlike the first encounter,

the Second Seminole War

showed the Seminoles to be a resourceful enemy. Led by their capable

leader Osceola

(1804-

xxxxxBut,xlike the first encounter,

the Second Seminole War

showed the Seminoles to be a resourceful enemy. Led by their capable

leader Osceola

(1804-

xxxxxInxthe Third Seminole War, waged from 1855 to 1858, the Indians again used their

bases in the Everglades to launch persistent raids upon white

settlements. Eventually, however, more U.S. troops were drafted into

the area, and they were forced to give up their struggle. Over 200

were re-

xxxxxIncidentally, there were also earlier instances of armed resistance against relocation amid the tribes north of the Ohio River. In 1832, for example, after the Sauk had been evicted from their homeland, their chief, Black Hawk, led his people back to their lands in Illinois, together with a contingent from the nearby Fox tribe. There they began planting crops again, but not for long. Federal troops were summoned, together with local militia forces, and in the Black Hawk War that followed the Indians stood little chance. They were defeated near the Wisconsin River in the July, and in the Bad Axe Massacre of the following month, and Black Hawk was forced to surrender. ……

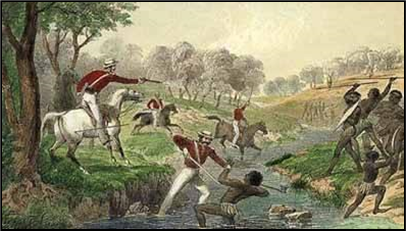

xxxxx…… Andxitxwas at this time that a similar attack upon an

indigenous population was carried out on the island of Tasmania. In

1828, after years of conflict between the native Aboriginals and the

British colonists -

xxxxx…… Andxitxwas at this time that a similar attack upon an

indigenous population was carried out on the island of Tasmania. In

1828, after years of conflict between the native Aboriginals and the

British colonists -

xxxxxA man who recorded on

canvas and in writing the unique way of life of the American Indian

and “rescued it from oblivion” -

Va-