xxxxxThe People’s Charter was drawn up by William Lovett, leader of The Workingmen’s Association, in 1838. The first national working class movement in Britain, it demanded widespread political reform, including universal male suffrage and voting by secret ballot. Following on from the affair known as the Tolpuddle Martyrs - when six farm labourers were deported for forming a union (1834 W4) - it aimed to improve the rights and living conditions of the working man and his family. Three petitions were presented to Parliament over the next ten years, but all were rejected. After the failure of the first in 1839, “Chartism” came under the influence of the militant Irish Member of Parliament Feargus Edward O’Conner. There was an uprising in Newport, Wales, followed by riots and strikes across northern England, Wales and Scotland, but they were quickly put down, and over sixty Chartists were sentenced to transportation. By 1848 the movement was at an end, but it was not without consequence. The German political philosopher Friedrich Engels, who, together with Karl Marx, founded Communism in 1848, supported Chartism whilst working in Manchester, and emigrants to Australia carried on the movement down under. In 1854 a protest in favour of political reform was crushed at the Eureka Stockade in the state of Victoria, but the ringleaders were acquitted, and the first steps towards democracy were taken.

CHARTISM

FIRST BRITISH WORKING CLASS MOVEMENT 1838 - 1848 (Va)

Acknowledgements

Chartism: by the English photographer William Edward Kilburn (1818-1891), 1848 – Royal Collection, UK. O’Connor: engraving, date and artist unknown. Engels: by English photographer George Lester, 1868. Rebecca Riots: from the Illustrated London News, 1843, artist unknown. Carlyle: detail, by the Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais (1829-1896), 1877 – National Portrait Gallery, London. Kingsley: by the English engraver Charles Henry Jeens (1827-1879), from a b/w photograph, originally published in 1876. Mary Kingsley: b/w photograph, contained in her work West African Study, 1899, artist unknown – private collection. Slessor: b/white photograph, contained in Mary Slessor of Calabar by the Scottish writer William Pringle Livingstone (1803-1883), first published in 1915, artist unknown. Map (Nigeria): licensed under Creative Commons. Author: CommonRollebon – https:// commons. wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ijaw.

xxxxxItxwas in May 1838 that The Workingmen’s Association, formed in London by the social reformer William Lovett (1800-1877) two years earlier, drew up the People’s Charter. Out of this grew the radical organisation known as Chartism, the first national working-class movement to be formed in Great Britain. The Charter demanded widespread political reform. Its six-point programme called for universal male suffrage, voting by secret ballot, equal electoral districts, annual parliaments, the abolition of the property qualification, and state salaries for members of Parliament.

xxxxxItxwas in May 1838 that The Workingmen’s Association, formed in London by the social reformer William Lovett (1800-1877) two years earlier, drew up the People’s Charter. Out of this grew the radical organisation known as Chartism, the first national working-class movement to be formed in Great Britain. The Charter demanded widespread political reform. Its six-point programme called for universal male suffrage, voting by secret ballot, equal electoral districts, annual parliaments, the abolition of the property qualification, and state salaries for members of Parliament.

xxxxxThe reasons for this movement were not difficult to find. Only four years earlier the affair known as the Tolpuddle Martyrs - in which six farm labourers from Dorset had been deported for forming a union (1834 W4) - had brought about the collapse of the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union on the industrial front. Meanwhile politically and socially the Reform Act of 1832 (W4) and the Poor Law Act of 1834 had done little to improve the rights or conditions of the working man. Although the worker had become a vital part in the Industrial Revolution and the wealth it generated, the living conditions under which he and his family lived and worked remained appalling. The working classes - many, in fact, not working - were housed in cramped, disease-ridden slums, and trapped in grinding poverty. This, together with a series of bad harvests had brought millions to the point of starvation.

xxxxxThree petitions were presented to Parliament over the next ten years, in 1839, 1842 and 1848, but despite the strength of feeling these apparently showed (3 million signed in 1842), all were rejected. Inxthe meantime Chartism came under the influence of the militant Irish member of Parliament Feargus Edward O’Connor (1794-1855) (illustrated), and the peaceful line taken by Lovell in his “New Move Chartism” was replaced by a resort to violence. In November 1839, for example, there was a rising in Newport, South Wales, but an attempt to break into the jail there was quickly crushed. Some twenty of the protestors were killed and three were sent to Australia. Then three years later there was a series of riots and strikes in the industrial areas of northern England, Wales and Scotland. Mills and factories were burnt down, and many of their owners were attacked and murdered. Troops were rushed to the trouble spots - many by train - and a further sixty Chartists were sentenced to transportation once the disturbances had been crushed.

xxxxxThree petitions were presented to Parliament over the next ten years, in 1839, 1842 and 1848, but despite the strength of feeling these apparently showed (3 million signed in 1842), all were rejected. Inxthe meantime Chartism came under the influence of the militant Irish member of Parliament Feargus Edward O’Connor (1794-1855) (illustrated), and the peaceful line taken by Lovell in his “New Move Chartism” was replaced by a resort to violence. In November 1839, for example, there was a rising in Newport, South Wales, but an attempt to break into the jail there was quickly crushed. Some twenty of the protestors were killed and three were sent to Australia. Then three years later there was a series of riots and strikes in the industrial areas of northern England, Wales and Scotland. Mills and factories were burnt down, and many of their owners were attacked and murdered. Troops were rushed to the trouble spots - many by train - and a further sixty Chartists were sentenced to transportation once the disturbances had been crushed.

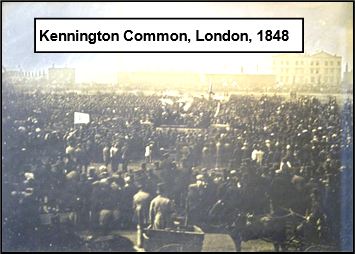

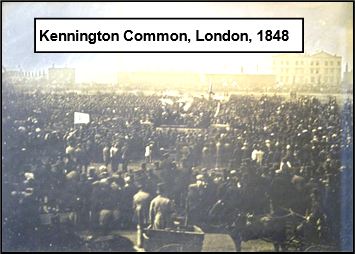

xxxxxThen In April 1848 - the year of revolutions throughout Europe - 150,000 demonstrators marched on Westminster to submit the last of the petitions - reputedly bearing five million signatures - and there were real fears of a general uprising. Some 10,000 troops were put on stand-by, and 200,000 special constables put on duty, but the event passed off without serious mishap. By then, despite the size of the protest, the movement itself had lost much of its impetus, subdued by swift police action and divided - as such organisations often were - by a conflict over the best tactics to adopt. Furthermore, the development of new unions provided an improved, albeit limited, means of protest. However, it was to be some seventy years before the major demands contained in the People’s Charter were to be met.

xxxxxNevertheless, indirectly, the Chartist movement played a significant role in world affairs. In 1842 the German social and political philosopher Friedrich Engels (illustrated) was working in a Manchester cotton factory and supported the aims of Chartism. Two years later he became friends with his fellow countryman Karl Marx and, as we shall see, it was these two men who produced the Communist Manifesto in 1848, a document which was destined to bring about profound changes in world affairs.

xxxxxAndxChartism had a knock-on effect on the other side of the globe. Many of the British emigrants who were going to Australia supported the movement and, on arrival, set up workingmen’s associations. One such organisation, the Ballarat Reform League, was responsible for the incident known as the Eureka Stockade when about 150 “diggers” (goldminers) took up arms in protest against a licence fee imposed on their right to search, and their lack of both the vote and political representation. When Victoria state troops arrived on the scene in November 1854, the diggers quickly constructed a wooden stockade in the Eureka goldfield, but the following month it was overrun in a matter of minutes. About 25 of the miners were killed, and the vast majority were taken prisoner. Thirteen were charged with treason, but all were acquitted in a trial which is seen today as the first glimmer of Australian democracy, and the beginning of much-needed reforms.

xxxxxWilliam Lovett was sent to prison for a year in 1839, and it was then that he and a fellow prisoner wrote Chartism: A New Organisation of the People. On coming to power, Feargus O’Connor used his journal, The Northern Star, to drum up support. Amongxothers who contributed to the movement were the English poet Thomas Cooper (1805-1892) whose epic The Purgatory of Suicides put into verse the principles of the Chartism, and the Irish-born radical James Bronterre O’Brien (1805-1864), editor of the influential The Poor Man’s Guardian from 1831 to 1835.

xxxxxIncidentally, the cause of the Chartists was in no way helped in 1848 when the last petition was sent to Parliament. O’Connor claimed that it contained five million signatures, though the number proved to be less than half that figure, and some of the signatures were clearly fictitious, and included those of Queen Victoria, the Duke of Wellington, and Mr Punch! ……

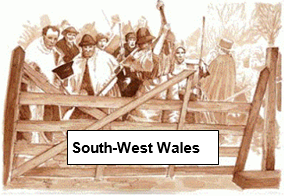

xxxxx…… Itxwasxduring the time of the Chartist agitation that the so-called Rebecca Riots broke out in the south-west of Wales. Though mainly held as a protest against the charges levied at tollgates, they were also a protest against the poverty and living conditions of those working on the land. The rioters, operating at night, destroyed gates and tollhouses across the region. Troops and police were called in, and by 1843 peace had been restored. An Act the following year did make a reduction in the tollgate charges.

xxxxx…… Itxwasxduring the time of the Chartist agitation that the so-called Rebecca Riots broke out in the south-west of Wales. Though mainly held as a protest against the charges levied at tollgates, they were also a protest against the poverty and living conditions of those working on the land. The rioters, operating at night, destroyed gates and tollhouses across the region. Troops and police were called in, and by 1843 peace had been restored. An Act the following year did make a reduction in the tollgate charges.

xxxxxThe name of the riots was taken from a prophecy in the Book of Genesis that the descendants of Rebecca would “possess the gate of those who hate them.” The leader of each band was named “Rebecca”, and his followers or “daughters”, were often disguised as women.

Including:

Thomas Carlyle and

Charles Kingsley

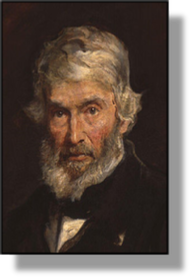

xxxxxThe Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) wrote a long essay on Chartism in 1839, but he is remembered today for his major work The French Revolution of 1837, his Letters and Speeches of Cromwell in 1845, and his six volume History of Friedrich II of Prussia (Frederick the Great), completed in 1865. Many of his works were concerned with the role of the “hero” in history, and he saw the seeds of anarchy within the growth of democracy and the decline in moral values. His picturesque style was not always easy to follow, but he produced a powerful commentary on the political and social conditions of his time. He numbered among his friends Edward Irving, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Matthew Arnold and Charles Dickens, and his criticism of Victorian society influenced the ideas of Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, the founders of Communism.

xxxxxThe Anglican priest Charles Kingsley (1819-1875) was deeply concerned with the plight of the poor on the land and in industry. His novel Yeast of 1848 highlighted the desperate living conditions of the farm labourer, and in his Alton Lock of 1850, the chief character rebels against the hardship of the factory system and becomes a leader in the Chartist movement. These works earned him the title “the Chartist clergyman”. Today, however, he is especially remembered for the historical adventure novels Westward Ho! and Hereward the Wake, and The Water Babies, a children’s fantasy tale published in 1863. In 1870 his At Last described his visit to the West Indies. Other works included The Wonders of the Shore and Roman and Teuton, and, as co-founder of the Christian Socialist Movement, he wrote numerous articles on the means of providing social relief, writing under the pen-name “Parson Lot”.

xxxxxThe Anglican priest Charles Kingsley (1819-1875) was deeply concerned with the plight of the poor on the land and in industry. His novel Yeast of 1848 highlighted the desperate living conditions of the farm labourer, and in his Alton Lock of 1850, the chief character rebels against the hardship of the factory system and becomes a leader in the Chartist movement. These works earned him the title “the Chartist clergyman”. Today, however, he is especially remembered for the historical adventure novels Westward Ho! and Hereward the Wake, and The Water Babies, a children’s fantasy tale published in 1863. In 1870 his At Last described his visit to the West Indies. Other works included The Wonders of the Shore and Roman and Teuton, and, as co-founder of the Christian Socialist Movement, he wrote numerous articles on the means of providing social relief, writing under the pen-name “Parson Lot”.

xxxxxKingsley was born at Holne Vicarage in Devon, and after studying at Cambridge University took holy orders, becoming rector of Eversley, Hampshire, in 1844. He was professor of modern history at Cambridge throughout the 1860s, and it was during that time that he became involved in a dispute with John Newman (later Cardinal) over his conversion to Roman Catholicism. He became chaplain to Queen Victoria in 1859, canon of Westminster in 1873. and, later, tutor to the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII.

xxxxxKingsley was born at Holne Vicarage in Devon, and after studying at Cambridge University took holy orders, becoming rector of Eversley, Hampshire, in 1844. He was professor of modern history at Cambridge throughout the 1860s, and it was during that time that he became involved in a dispute with John Newman (later Cardinal) over his conversion to Roman Catholicism. He became chaplain to Queen Victoria in 1859, canon of Westminster in 1873. and, later, tutor to the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII.

xxxxxIncidentally, he was one of the first Anglican clergymen to give wholehearted support to Charles Darwin’s doctrine of evolution and natural selection. ……

xxxxx…… His younger brother Henry Kingsley was also a novelist, and it was he who, in 1863, persuaded the story-teller Lewis Carroll to publish his stories about Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. ……

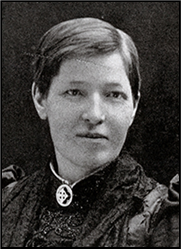

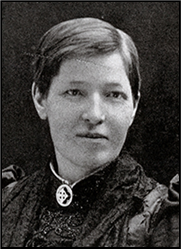

xxxxx…… Kingsley’sxniece, Mary Kingsley (1862-1900) was also a writer. After the death of her parents in 1892 she made two pioneering journeys to West Africa, travelling alone in difficult and dangerous terrain, and learning about the life and culture of the native people by firsthand experience. Her two books, Travels in West Africa of 1897 and West African Studies, published in 1899, proved very popular, but her criticism of certain aspects of colonial rule and the work of the missionaries displeased both the government and the Church of England. She was anxious that the natives continued to follow their own way of life, despite the coming of the white man. When the Second Anglo-Boer War broke out in 1899 she went out to South Africa to serve as a nurse, but the following year, while caring for the sick and wounded, she caught typhoid fever and died in the June. ……

xxxxx…… Kingsley’sxniece, Mary Kingsley (1862-1900) was also a writer. After the death of her parents in 1892 she made two pioneering journeys to West Africa, travelling alone in difficult and dangerous terrain, and learning about the life and culture of the native people by firsthand experience. Her two books, Travels in West Africa of 1897 and West African Studies, published in 1899, proved very popular, but her criticism of certain aspects of colonial rule and the work of the missionaries displeased both the government and the Church of England. She was anxious that the natives continued to follow their own way of life, despite the coming of the white man. When the Second Anglo-Boer War broke out in 1899 she went out to South Africa to serve as a nurse, but the following year, while caring for the sick and wounded, she caught typhoid fever and died in the June. ……

xxxxx…… Inx1895, while exploring in Africa, Mary Kingsley met the Scottish missionary Mary Slessor (1848-1915). Her father was an alcoholic and so from the age of eleven she worked a ten hour day in a local jute factory in order to provide for her family. A committed church goer, she was inspired by the exploits of the explorer David Livingstone, and at his death in 1874 resolved to serve as a missionary in Africa. The following year, at the age of 27, she travelled to Calabar in today’s Nigeria (arrowed), and spent the rest of her life in the service of the local natives. At first she worked as a teacher but, following a period of leave in England - during which she told of her work - she returned to live among the people, setting up schools, churches and hospitals to improve their lives, and striving to put an end to the constant fighting between the local tribes. She was particularly concerned about the custom of killing twins at birth - in the belief that they were born of the devil - and made some headway in putting an end to this barbaric practice. Over the years she gathered around her a “family” of adopted children, and won the affection and respect of the local tribal chiefs. She suffered from severe arthritis in her later years, but refused to leave Africa, and died in Calabar in 1915, the place where she had begun her missionary work forty years earlier.

xxxxx…… Inx1895, while exploring in Africa, Mary Kingsley met the Scottish missionary Mary Slessor (1848-1915). Her father was an alcoholic and so from the age of eleven she worked a ten hour day in a local jute factory in order to provide for her family. A committed church goer, she was inspired by the exploits of the explorer David Livingstone, and at his death in 1874 resolved to serve as a missionary in Africa. The following year, at the age of 27, she travelled to Calabar in today’s Nigeria (arrowed), and spent the rest of her life in the service of the local natives. At first she worked as a teacher but, following a period of leave in England - during which she told of her work - she returned to live among the people, setting up schools, churches and hospitals to improve their lives, and striving to put an end to the constant fighting between the local tribes. She was particularly concerned about the custom of killing twins at birth - in the belief that they were born of the devil - and made some headway in putting an end to this barbaric practice. Over the years she gathered around her a “family” of adopted children, and won the affection and respect of the local tribal chiefs. She suffered from severe arthritis in her later years, but refused to leave Africa, and died in Calabar in 1915, the place where she had begun her missionary work forty years earlier.

xxxxxIn 1839 the Scottish social historian and critic Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) wrote a long essay on Chartism in which he roundly attacked the doctrine of laissez faire - the theory that the state should take no part in the country’s economic affairs. Today, however, he is best remembered for his major work The French Revolution of 1837, his On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History of 1841, his Letters and Speeches of Cromwell in 1845, and his longest work, a six volume History of Friedrich II of Prussia (Frederick the Great) produced from 1858 to 1865.

xxxxxIn 1839 the Scottish social historian and critic Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) wrote a long essay on Chartism in which he roundly attacked the doctrine of laissez faire - the theory that the state should take no part in the country’s economic affairs. Today, however, he is best remembered for his major work The French Revolution of 1837, his On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History of 1841, his Letters and Speeches of Cromwell in 1845, and his longest work, a six volume History of Friedrich II of Prussia (Frederick the Great) produced from 1858 to 1865.

xxxxxHis belief in the importance of heroes, men of vision and courage, coloured much of his work. He saw the need for strong leaders like Cromwell, Frederick the Great and Napoleon Bonaparte to push mankind towards higher goals,  however ruthless their own contribution might be in the short term. Such men, convinced that they were an instrument of God, were the means by which social justice would eventually be achieved. In later life, however, he took a more pessimistic view. He despaired of Victorian society, seeing seeds of anarchy within the growth of democracy and the decline in moral values. He thus opposed the drive towards “universal suffrage”, regarding it as a mere “counting of heads”. His Past and Present, published in 1843, developed this idea of the hero, comparing the strict but wise rule of a medieval abbot with the political turmoil of his own troubled century. Then in 1850 came Latter Day Pamphlets, a series of blistering attacks upon the shortcomings of Victorian society.

however ruthless their own contribution might be in the short term. Such men, convinced that they were an instrument of God, were the means by which social justice would eventually be achieved. In later life, however, he took a more pessimistic view. He despaired of Victorian society, seeing seeds of anarchy within the growth of democracy and the decline in moral values. He thus opposed the drive towards “universal suffrage”, regarding it as a mere “counting of heads”. His Past and Present, published in 1843, developed this idea of the hero, comparing the strict but wise rule of a medieval abbot with the political turmoil of his own troubled century. Then in 1850 came Latter Day Pamphlets, a series of blistering attacks upon the shortcomings of Victorian society.

xxxxxCarlyle was born in Ecclefechan, Dumfriesshire, a member of a devout Calvinist family. After studying at Edinburgh University, he abandoned any ideas of the ministry, and taught at Annan Academy and a school at Kirkcaldy before moving to Edinburgh in 1818. There, working as a tutor, he immersed himself in the study of German literature, translating Goethe’s Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre, and writing the life of the poet and playwright Friedrich von Schiller. After his marriage in 1826, he lived on a remote farm at Craigenputtock, Dumfriesshire, and it was there that he wrote Sartor Resartus (The Tailor Retailored), a philosophical study in which he questioned certain aspects of his faith, but affirmed his spiritual idealism, and continued to stress the importance of self-denial and the dignity of work. It was in this strange mixture of a work that he drew attention to the appalling living conditions of the country’s working classes.

xxxxxIn 1834 he moved to Chelsea, London, - where he became known as the “Sage of Chelsea” - and joined a flourishing literary circle which included the English poet Leigh Hunt and the economic philosopher John Stuart Mill. It was then that he began his most ambitious historical work The French Revolution (illustrated), a well-documented appraisal in which he blamed the indifference and selfishness of the monarchy and nobility for the extreme suffering of the country’s poor. There followed his work on heroes which, in addition to military giants, included literary figures as far apart as Dante and Samuel Johnson, and religious leaders as diverse as Muhammad and John Knox. His Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches was published in 1845, and his last major work, the history of Frederick the Great, was completed twenty years later.

xxxxxThe accuracy of his work proved suspect at times, and his prose, grandiose and full of imagery, was often difficult to follow, and sometimes obscure. Nonetheless, his vivid, picturesque style conveyed history as it had not been conveyed before, and, by contrasting the present with the past, he provided a powerful commentary on the social and political issues of his time. Apartxfrom Hunt and Mill, his acquaintances included Matthew Arnold and Charles Dickens (who dedicated Hard Times to him), and he made life-long friendships with the Scottish cleric and mystic Edward Irving (1792-1834) and the American essayist and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson. And his criticism of Victorian society, particularly in the realm of industry, influenced the ideas of the German philosophers Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, the founders of Communism.

xxxxxIncidentally, in 1881 Westminster Abbey was offered as his place of burial, but in accordance with his wishes, he was buried alongside his parents at Ecclefechan. His house in Cheyne Row, Chelsea, where he and his wife lived from 1834, is now a museum dedicated to his life and works. ……

xxxxx…… In the mid 1830s Carlyle suffered a serious setback when his friend John Stuart Mill, having been loaned the partly completed manuscript of the French Revolution, put it in the fire by mistake! For Carlyle this meant months of wasted time and effort but, according to all accounts, he accepted the accident with surprisingly good grace. He started the work again and, writing at a furious pace, completed the work early in 1837.

xxxxxAs an Anglican priest, Charles Kingsley (1819-1875) was deeply concerned with the plight of the poor. When he turned to writing, his novels Yeast of 1848 and Alton Lock, published two years later, earned him the title “the Chartist clergyman”. Today he is especially remembered for his two historical novels, Westward Ho! and Hereward the Wake, and The Water Babies, a fantasy tale published in 1863. He was professor of modern History at Cambridge throughout the 1860s, and it was during that time that he was in dispute with John Newman over his conversion to Roman Catholicism. For some years Kingsley was chaplain to Queen Victoria and tutor to the Prince of Wales.

Va-1837-1861-Va-1837-1861-Va-1837-1861-Va-1837-1861-Va-1837-1861-Va-1837-1861-Va

xxxxxItxwas in May 1838 that The Workingmen’s Association, formed in London by the social reformer William Lovett (1800-

xxxxxItxwas in May 1838 that The Workingmen’s Association, formed in London by the social reformer William Lovett (1800- xxxxxThree petitions were presented to Parliament over the next ten years, in 1839, 1842 and 1848, but despite the strength of feeling these apparently showed (3 million signed in 1842), all were rejected. Inxthe meantime Chartism came under the influence of the militant Irish member of Parliament Feargus Edward O’Connor (1794-

xxxxxThree petitions were presented to Parliament over the next ten years, in 1839, 1842 and 1848, but despite the strength of feeling these apparently showed (3 million signed in 1842), all were rejected. Inxthe meantime Chartism came under the influence of the militant Irish member of Parliament Feargus Edward O’Connor (1794-

xxxxx…… Itxwasxduring the time of the Chartist agitation that the so-

xxxxx…… Itxwasxduring the time of the Chartist agitation that the so-

xxxxxThe Anglican priest Charles Kingsley (1819-

xxxxxThe Anglican priest Charles Kingsley (1819- xxxxxKingsley was born at Holne Vicarage in Devon, and after studying at Cambridge University took holy orders, becoming rector of Eversley, Hampshire, in 1844. He was professor of modern history at Cambridge throughout the 1860s, and it was during that time that he became involved in a dispute with John Newman (later Cardinal) over his conversion to Roman Catholicism. He became chaplain to Queen Victoria in 1859, canon of Westminster in 1873. and, later, tutor to the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII.

xxxxxKingsley was born at Holne Vicarage in Devon, and after studying at Cambridge University took holy orders, becoming rector of Eversley, Hampshire, in 1844. He was professor of modern history at Cambridge throughout the 1860s, and it was during that time that he became involved in a dispute with John Newman (later Cardinal) over his conversion to Roman Catholicism. He became chaplain to Queen Victoria in 1859, canon of Westminster in 1873. and, later, tutor to the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII.  xxxxx…… Kingsley’sxniece, Mary Kingsley (1862-

xxxxx…… Kingsley’sxniece, Mary Kingsley (1862-

xxxxx…… Inx1895, while exploring in Africa, Mary Kingsley met the Scottish missionary Mary Slessor (1848-

xxxxx…… Inx1895, while exploring in Africa, Mary Kingsley met the Scottish missionary Mary Slessor (1848- xxxxxIn 1839 the Scottish social historian and critic Thomas Carlyle (1795-

xxxxxIn 1839 the Scottish social historian and critic Thomas Carlyle (1795- however ruthless their own contribution might be in the short term. Such men, convinced that they were an instrument of God, were the means by which social justice would eventually be achieved. In later life, however, he took a more pessimistic view. He despaired of Victorian society, seeing seeds of anarchy within the growth of democracy and the decline in moral values. He thus opposed the drive towards “universal suffrage”, regarding it as a mere “counting of heads”. His Past and Present, published in 1843, developed this idea of the hero, comparing the strict but wise rule of a medieval abbot with the political turmoil of his own troubled century. Then in 1850 came Latter Day Pamphlets, a series of blistering attacks upon the shortcomings of Victorian society.

however ruthless their own contribution might be in the short term. Such men, convinced that they were an instrument of God, were the means by which social justice would eventually be achieved. In later life, however, he took a more pessimistic view. He despaired of Victorian society, seeing seeds of anarchy within the growth of democracy and the decline in moral values. He thus opposed the drive towards “universal suffrage”, regarding it as a mere “counting of heads”. His Past and Present, published in 1843, developed this idea of the hero, comparing the strict but wise rule of a medieval abbot with the political turmoil of his own troubled century. Then in 1850 came Latter Day Pamphlets, a series of blistering attacks upon the shortcomings of Victorian society.