CARPINI, JOHANNES DE PLANO c1182 -

(H2, R1, JO, H3)

Including:

William of

Rubruquis

xxxxxIn 1245 Carpini, one of the original followers of Francis of Assisi, led the first papal mission to the Mongols. After an arduous journey, including 3,000 miles across central Asia, they reached Sira Ordu and had an audience with the Great Khan Kuyuk. They had hoped to receive an assurance from him that he would make no further attacks upon eastern Europe, but they were disappointed. He sent them back home in 1247 with a letter confirming that he was “the scourge of God”! The only positive outcome from the visit was Carpini's detailed account of the mission, contained in his The Book of the Tartars. Made up of nine chapters, this dealt with different aspects of the country and described the journey there and back.

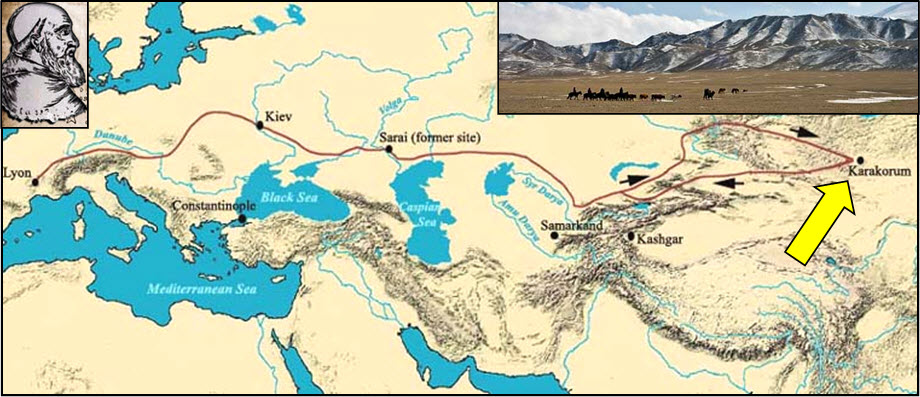

xxxxxCarpini, an Italian Franciscan friar from Perugia, and one of the original followers of Francis of Assisi, led the first official papal mission to the Mongols. The mission, sent by Pope Innocent IV (illustrated), set out in 1245 on a route which would take them north of the Caspian and Aral Seas. In April 1246, having reached Baku on the western frontier of the Mongol Empire, the party was given permission to travel to the court of the supreme Khan. This phase of the journey, crossing as it did the vast lands of central Asia, was arduous in the extreme. The party rode some 3,000 miles over the next fifteen days, arriving at the imperial camp of Sira Ordu -

xxxxxCarpini, an Italian Franciscan friar from Perugia, and one of the original followers of Francis of Assisi, led the first official papal mission to the Mongols. The mission, sent by Pope Innocent IV (illustrated), set out in 1245 on a route which would take them north of the Caspian and Aral Seas. In April 1246, having reached Baku on the western frontier of the Mongol Empire, the party was given permission to travel to the court of the supreme Khan. This phase of the journey, crossing as it did the vast lands of central Asia, was arduous in the extreme. The party rode some 3,000 miles over the next fifteen days, arriving at the imperial camp of Sira Ordu -

xxxxxAfter witnessing the enthronement of the new Emperor, the Great Khan Kuyuk, they were granted an audience with him. The Pope had hoped that the friars would persuade the Mongol leader not to make further attacks upon eastern Europe, but no such guarantee was forthcoming. Indeed, Kuyuk, having detained the legates until November, sent them back with a letter simply confirming the role of the Great Khan as “the scourge of God”. Nor did the weather relent. The winter conditions made the return journey even worse than the outward one, and they did not reach Lyon and the Pope until the summer of 1247.

xxxxxBut the mission had one positive result. Immediately on his return, Carpini wrote out in Latin a detailed account of the journey and of the time spent at the court of the Great Khan. Apart from being the first authentic report on the Mongolian Empire and the threat it posed to Europe, it also helped to dispel much of the fable and myth which had come to surround these distant people. Popularly known as The Book of the Tartars, the work was divided into nine chapters, each one dealing with an aspect of the country, its people, and its rulers. Apart from the hardships suffered on the long outward and return journeys, these chapters covered such matters as the geography, climate, customs, way of life and character of this vast empire and its people.

H3-

Acknowledgements

Innocent IV: illustration by the 15th century French artist Mâitre de la Cité des Dames, 1400-

xxxxxAnother member of the mission, Benedict the Pole, also wrote a partial account of the visit, but it was left to William of Rubruquis a few years later to produce an account which equals that of Carpini's in detail and width. A French Franciscan friar, he was sent as a papal envoy to the Mongols in 1253 and, like Carpini before him, proved to be an honest, first-