xxxxxWhen Ferdinand VII returned as king of Spain in 1814, he agreed to accept the democratic form of government which had been established two years earlier. However, once in power he abrogated the new constitution and restored a reactionary regime. In a revolution in 1820 parliamentary government was restored, but not for long. Via the Holy Alliance the French sent in a large army, and Ferdinand regained his throne. With his death in 1833, however, troubles broke out again. He was succeeded by his daughter, Isabella, just three years old, but his brother, Don Carlos, claimed the throne for himself and began the First Carlist War. An arch reactionary, he gained support from the mountain provinces of the north, who wanted their own independence, but his guerrilla forces proved no match for the “Cristinos”, the supporters of the regent, Maria Cristina (Isabella’s mother). She commanded a regular army, and was aided by Britain, France and Portugal, countries opposed to reactionary regimes. The Carlists accepted defeat in 1839, and a further war, waged from 1846 to 1849 also proved unsuccessful. By that time Isabella was on the throne, and the country was in a state of constant political unrest. She survived an attempt to overthrow her in 1866 but, as we shall see, she was driven into exile in 1868 (Vb). She abdicated in favour of her son, Alfonso, but he did not succeed to the throne until the Third Carlist War (1872-1876) had virtually run its course.

SPAIN AND THE FIRST CARLIST WAR 1833 - 1839 (W4, Va)

Acknowledgements

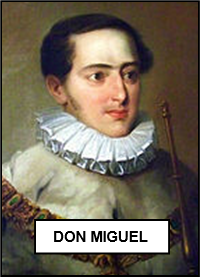

Ferdinand VII: by the Spanish painter Luis Lopez Piquer (1802-1865) – Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, Madrid. Battle: date and artist unknown. Isabella II: engraving, date and artist unknown – New York Public Library, USA. Miguel: date and artist unknown. Pedro: by the English portrait painter John Simpson (1782-1847), 1834 – National Coach Museum, Lisbon. Clausewitz: by the German painter Karl Wilhelm Wach (1787-1845), c1810. Scharnhorst: by the German painter Johann Friedrich Bury (1763-1823), c1810.

xxxxxIt was during a dispute between Charles IV and his son Ferdinand in 1808 that Napoleon intervened and put his own brother Joseph Bonaparte on the Spanish throne. As we have seen, this resulted in the Peninsular War and British military intervention in 1808 (G3c). The defeat and final expulsion of the French from the peninsula took some six years to achieve, but during this time the Spanish people - given the absence of their king and much of the country’s nobility - established the Cortes of Cadiz, a parliament which, dominated by members of the middle class, adopted a democratic form of government.

xxxxxFerdinandxVII (1784-1833) (illustrated), held prisoner in France at this time, pledged to uphold this constitution on his return to Spain, but when he eventually came to the throne in 1814, he wasted no time in turning back the political clock. He abrogated the new constitution, restored the religious orders, re-established the Inquisition and, in effect, resurrected the Spanish absolute monarchy of the previous century. The brutal, reactionary regime he then introduced led to the inevitable backlash. In a revolution of 1820, supported by the army, the liberal constitution was in fact restored. Ferdinand was obliged to accept it, but it proved of short duration. In 1823 the Holy Alliance gave France the task of putting down this experiment in democracy, and this was quickly achieved by the despatch of a large French army. Ferdinand was restored to power and quickly took his revenge on the liberal-minded, arresting them or driving them into exile. By now, however, the country was near to bankruptcy, due in large part to the loss of its colonies overseas. Spanish possessions on the mainland of South America had gained or were in the throes of gaining their independence, thanks to the endeavours of freedom fighters like San Martin and Simon Bolivar.

xxxxxFerdinandxVII (1784-1833) (illustrated), held prisoner in France at this time, pledged to uphold this constitution on his return to Spain, but when he eventually came to the throne in 1814, he wasted no time in turning back the political clock. He abrogated the new constitution, restored the religious orders, re-established the Inquisition and, in effect, resurrected the Spanish absolute monarchy of the previous century. The brutal, reactionary regime he then introduced led to the inevitable backlash. In a revolution of 1820, supported by the army, the liberal constitution was in fact restored. Ferdinand was obliged to accept it, but it proved of short duration. In 1823 the Holy Alliance gave France the task of putting down this experiment in democracy, and this was quickly achieved by the despatch of a large French army. Ferdinand was restored to power and quickly took his revenge on the liberal-minded, arresting them or driving them into exile. By now, however, the country was near to bankruptcy, due in large part to the loss of its colonies overseas. Spanish possessions on the mainland of South America had gained or were in the throes of gaining their independence, thanks to the endeavours of freedom fighters like San Martin and Simon Bolivar.

xxxxxWith the death of Ferdinand in 1833 trouble flared up once again. Having no male heir, he had designated his three-year-old daughter Isabella as his successor. In order to do this he had obtained a decree from the Cortes setting aside the Salic Law (which forbade the succession of a woman), but nonetheless, - and not surprisingly perhaps - the succession was opposed. Hisxbrother, Don Carlos de Bourbon (1788-1855), claimed the throne, and his large body of supporters soon came to be known as Carlists. These were die-hard conservatives - with many Church leaders among them - who favoured absolute monarchy and opposed liberal views and any form of parliamentary democracy. To counter this threat, Isabella’s mother Maria Cristina, acting as regent, was obliged to turn for support to the liberal democrats, promising the Cortes greater powers in central government. This action simply served to draw the battle lines between the two opposing factions, the Carlists and the Cristinos (or Isabelinos), and when, in 1833, Don Carlos had himself proclaimed King Charles V, civil war was inevitable.

xxxxxWith the death of Ferdinand in 1833 trouble flared up once again. Having no male heir, he had designated his three-year-old daughter Isabella as his successor. In order to do this he had obtained a decree from the Cortes setting aside the Salic Law (which forbade the succession of a woman), but nonetheless, - and not surprisingly perhaps - the succession was opposed. Hisxbrother, Don Carlos de Bourbon (1788-1855), claimed the throne, and his large body of supporters soon came to be known as Carlists. These were die-hard conservatives - with many Church leaders among them - who favoured absolute monarchy and opposed liberal views and any form of parliamentary democracy. To counter this threat, Isabella’s mother Maria Cristina, acting as regent, was obliged to turn for support to the liberal democrats, promising the Cortes greater powers in central government. This action simply served to draw the battle lines between the two opposing factions, the Carlists and the Cristinos (or Isabelinos), and when, in 1833, Don Carlos had himself proclaimed King Charles V, civil war was inevitable.

xxxxxThe savage conflict that followed - the First Carlist War - raged for seven years and, for much of that time, was confined to the north of the country. In this region the Carlists gained the support of the people of the mountain provinces, notably the Basques and Catalans, who were fiercely independent and determined to retain their identity and traditional liberties. The Carlists enjoyed some early success, notably under their generals Tomas Zumalacarregui and Ramon Cabrera, but for the most part they could not break through into the south, and an attack upon Madrid, led by Don Carlos in 1837, ended in failure. In the event, their semi-guerrilla forces proved no match for a regular royalist army which was aided by Great Britain, France and Portugal, countries opposed to reactionary regimes. Furthermore, the Cristinos had the able services of their commander-in-chief Baldomero Espartero (1793-1879). Remembered especially for his victory at the Battle of Luchana in December 1836, he later initiated the negotiations which led to the Convention of Vergara in 1839 - bringing an end to the war - and he then served as regent from 1841 until his overthrow two years later.

xxxxxIsabella II (1830-1904) (illustrated) took over the reins of government at the age of thirteen following the fall of Espartero in 1843. Her troubled reign, compounded by her own incompetence, was marked by constant political unrest and a series of uprisings. Most serious amongst these was the Second Carlist War of 1846 to 1848, a continuation of the struggle between those who supported an absolute monarch and those determined to establish a parliamentary system of government. Ramon Cabrera returned to Spain to lead an uprising in Catalonia, but it proved unsuccessful and he was forced to leave Spain a second time. But Isabella’s overthrow was only a matter of time. In 1866 she survived another attempt to depose her, but with the death over the next two years of her major advisors, - two generals who had virtually run the country for her - she could no longer hang on to power. In the autumn of 1868 (Vb) came yet another revolution and this time she was driven into exile. She took refuge in France and two years later abdicated in favour of her son, Alfonso, but he did not succeed to the throne until 1875, after the Third Carlist War (1872-1876) had almost run its course.

xxxxxIsabella II (1830-1904) (illustrated) took over the reins of government at the age of thirteen following the fall of Espartero in 1843. Her troubled reign, compounded by her own incompetence, was marked by constant political unrest and a series of uprisings. Most serious amongst these was the Second Carlist War of 1846 to 1848, a continuation of the struggle between those who supported an absolute monarch and those determined to establish a parliamentary system of government. Ramon Cabrera returned to Spain to lead an uprising in Catalonia, but it proved unsuccessful and he was forced to leave Spain a second time. But Isabella’s overthrow was only a matter of time. In 1866 she survived another attempt to depose her, but with the death over the next two years of her major advisors, - two generals who had virtually run the country for her - she could no longer hang on to power. In the autumn of 1868 (Vb) came yet another revolution and this time she was driven into exile. She took refuge in France and two years later abdicated in favour of her son, Alfonso, but he did not succeed to the throne until 1875, after the Third Carlist War (1872-1876) had almost run its course.

Including:

The War of the Two

Brothers in Portugal,

and Carl von Clausewitz

W4-1830-1837-W4-1830-1837-W4-1830-1837-W4-1830-1837-W4-1830-1837-W4-1830-1837-W4

xxxxxSimilar troubles were encountered in Portugal at this time, culminating in the so-called War of the Two Brothers. When John VI died in 1826 his son Pedro, emperor of Brazil, gave over the throne to his young daughter Maria da Gloria. Power, however, was vested in her uncle Miguel, Pedro’s brother, and he seized the throne in 1828. In the war that followed Pedro was assisted by the British, and Miguel was eventually defeated in 1834. On the death of Pedro that year, Maria da Gloria, came to the throne as Maria II. She favoured a degree of liberalisation, but like her father’s constitution, parliament remained strictly under the control of the monarchy. And this was the general pattern of government which, despite political unrest, remained in force in Portugal until the country became a republic in 1910.

xxxxxIt was in this year, 1833, that the book Vom Krieg (On War) was published, the work of the Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz (1780-1831). This three-volume treatise, published posthumously, exerted a powerful influence on the thinking of military strategists well into the 20th century. Once a conflict had been started, he saw the destruction of the enemy’s forces as a country’s principal aim, but war, he argued, had to be seen as an extension of political policy by other means, not as an action pursued for its own sake.

xxxxxIt was in this year, 1833, that the book Vom Krieg (On War) was published, the work of the Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz (1780-1831). This three-volume treatise, published posthumously, exerted a powerful influence on the thinking of military strategists well into the 20th century. Once a conflict had been started, he saw the destruction of the enemy’s forces as a country’s principal aim, but war, he argued, had to be seen as an extension of political policy by other means, not as an action pursued for its own sake.

xxxxxClausewitz was born in Burg, near Magdeburg, and joined the Prussian army as a cadet in 1792, aged 12. He fought against the French Revolutionary army in the Rhine campaign of the early 1790s, and, having gained a commission, studied military science at the Berlin Military Academy from 1801 to 1804. During the Napoleonic Wars he was wounded and taken prisoner at Prenziau during the Jena campaign of 1806, but was exchanged as a prisoner two years later and returned to Berlin. He was then much involved in army reform, but in 1812 resigned his commission to serve in the Russian army during Napoleon’s invasion of Russia and retreat from Moscow. He re-enlisted in the Prussian army in 1815 and served as chief of staff to one of the corps at the Battle of Waterloo. Following the final overthrow of Napoleon, he was made a major general in 1818 and appointed director of the War College in Berlin. It was during his twelve years in this post that he put his mind to the compiling of Vom Krieg, drawing upon the experiences of such leaders as Frederick the Great and Napoleon himself. He died of cholera after paying a visit to the Polish frontier to supervise the observation of the Polish revolution of 1830.

xxxxxVom Kriege, in its broadest terms, was a study of the relationship between war, politics and general society. If war had to be waged then, in the majority of cases, it had to be a total conflict in which maximum force was concentrated on decisive points in order to bring about a quick and decisive destruction of the enemy. In such circumstances, attack should be directed not only against an enemy’s military forces, but also upon the resources which enabled it to wage a war, and the strength of an enemy’s will to fight, measured not only by the resolve of its leaders but also by that of the people themselves. At the same time, however, Clausewitz argued that war in any of its forms should be seen as a political instrument, and should only be embarked upon as part of a political strategy. Military action, he argued, was “simply a continuation of political intercourse” and its use should be conducted and restricted along “political lines”. Furthermore, there were instances when, for good political reasons, total war was not appropriate. Military action might well be limited to the occupation of a city or a piece of territory in order to force a favourable and peaceful settlement. And it followed that if war were a political act, then its ultimate direction should be in the hands of a country’s political leaders, with the military using their skills to fulfil the aims of the nation.

xxxxxVom Kriege, in its broadest terms, was a study of the relationship between war, politics and general society. If war had to be waged then, in the majority of cases, it had to be a total conflict in which maximum force was concentrated on decisive points in order to bring about a quick and decisive destruction of the enemy. In such circumstances, attack should be directed not only against an enemy’s military forces, but also upon the resources which enabled it to wage a war, and the strength of an enemy’s will to fight, measured not only by the resolve of its leaders but also by that of the people themselves. At the same time, however, Clausewitz argued that war in any of its forms should be seen as a political instrument, and should only be embarked upon as part of a political strategy. Military action, he argued, was “simply a continuation of political intercourse” and its use should be conducted and restricted along “political lines”. Furthermore, there were instances when, for good political reasons, total war was not appropriate. Military action might well be limited to the occupation of a city or a piece of territory in order to force a favourable and peaceful settlement. And it followed that if war were a political act, then its ultimate direction should be in the hands of a country’s political leaders, with the military using their skills to fulfil the aims of the nation.

xxxxxWritten in an readable style, and with a minimum of technical jargon, Vom Krieg proved of interest to the general public, and had a profound influence on military thinking at the strategic level. It was studied widely outside of Germany, and proved of particular interest to Lenin, the future communist leader of Russia. In Germany, Clausewitz’s writings clearly made an impression on the Prussian General Helmuth von Moltke, the man who was to employ total war to win victories over the Danes, Austrians and French. However, neither he nor later German generals were prepared to accept political c ontrol of military strategy.

ontrol of military strategy.

xxxxxIncidentally, Clausewitz was influenced and befriended by Gerhard von Scharnhorst (1755-1813), the Prussian general responsible for the reform of the Prussian army after its disastrous defeat at the Battle of Jena in 1806. Scharnhorst taught him military science at the Berlin Military Academy, introduced him at court, and made him his assistant when he started work on improving the army in 1808.

xxxxxPortugal experienced a similar period of political unrest at this same time, culminating in the so-called War of the Two Brothers 1828 to 1833. The king, John VI, had fled to Brazil at the outbreak of the Peninsular War and by the time he returned in 1820 a more democratic form of government had been established, but it was not to last. With John’s death in 1826 his son Pedro, emperor of Brazil, gave up the Portuguese throne in favour of his seven-year-old daughter Maria da Gloria, and power was vested in her uncle Miguel, Pedro’s brother. Within two years he had established a reactionary régime and, with the support of the conservative elements - the nobility, the army and the Church - had declared himself king.

xxxxxPedro, who was prepared to fight for a parliamentary system provided it remained under the authority of the Crown, at once sailed to Europe to raise an army against his brother. It landed near Porto in July 1832, but was besieged in that city for more than a year. In June 1833, however, a second force, supported by British troops, landed in the Algarve and captured Lisbon the following month, bringing an end to the War of the Two Brothers. Miguel went into exile in June 1834, Pedro died a few months later, and Maria de Gloria became queen as Maria II. Whilst in favour of some measure of liberalisation, she supported her father’s particular form of constitution and, despite continued political unrest, it was this pattern which generally remained in force in Portugal until the country became a republic in 1910.

xxxxxPedro, who was prepared to fight for a parliamentary system provided it remained under the authority of the Crown, at once sailed to Europe to raise an army against his brother. It landed near Porto in July 1832, but was besieged in that city for more than a year. In June 1833, however, a second force, supported by British troops, landed in the Algarve and captured Lisbon the following month, bringing an end to the War of the Two Brothers. Miguel went into exile in June 1834, Pedro died a few months later, and Maria de Gloria became queen as Maria II. Whilst in favour of some measure of liberalisation, she supported her father’s particular form of constitution and, despite continued political unrest, it was this pattern which generally remained in force in Portugal until the country became a republic in 1910.

xxxxxIt was in this year, 1833, that Vom Krieg (On War) was published posthumously, the work of the Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz (1780-1831). He had a distinguished career in the Prussian army, and after the fall of Napoleon, he was made a general in 1818 and appointed director of the War College in Berlin. He held this office for twelve years, and it was during this time that he wrote his three-volume masterpiece on the science of war. In this work he came out in support of total war as a means of defeating one’s enemy, but he insisted that war should be used as a political instrument, not as an end in itself. It followed that the aims of war should be in the hands of political leaders, with the military working to fulfil the wishes of the nation. This work had a wide and profound influence on military strategy, the communist leader Lenin being particularly interested in its teachings. In Germany, however, whilst the idea of a total war was readily accepted, the generals were not prepared to accept political control of military strategy.

xxxxxFerdinandxVII (1784-

xxxxxFerdinandxVII (1784- xxxxxWith the death of Ferdinand in 1833 trouble flared up once again. Having no male heir, he had designated his three-

xxxxxWith the death of Ferdinand in 1833 trouble flared up once again. Having no male heir, he had designated his three- xxxxxIsabella II (1830-

xxxxxIsabella II (1830-

xxxxxIt was in this year, 1833, that the book Vom Krieg (On War) was published, the work of the Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz (1780-

xxxxxIt was in this year, 1833, that the book Vom Krieg (On War) was published, the work of the Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz (1780- xxxxxVom Kriege, in its broadest terms, was a study of the relationship between war, politics and general society. If war had to be waged then, in the majority of cases, it had to be a total conflict in which maximum force was concentrated on decisive points in order to bring about a quick and decisive destruction of the enemy. In such circumstances, attack should be directed not only against an enemy’s military forces, but also upon the resources which enabled it to wage a war, and the strength of an enemy’s will to fight, measured not only by the resolve of its leaders but also by that of the people themselves. At the same time, however, Clausewitz argued that war in any of its forms should be seen as a political instrument, and should only be embarked upon as part of a political strategy. Military action, he argued, was “simply a continuation of political intercourse” and its use should be conducted and restricted along “political lines”. Furthermore, there were instances when, for good political reasons, total war was not appropriate. Military action might well be limited to the occupation of a city or a piece of territory in order to force a favourable and peaceful settlement. And it followed that if war were a political act, then its ultimate direction should be in the hands of a country’s political leaders, with the military using their skills to fulfil the aims of the nation.

xxxxxVom Kriege, in its broadest terms, was a study of the relationship between war, politics and general society. If war had to be waged then, in the majority of cases, it had to be a total conflict in which maximum force was concentrated on decisive points in order to bring about a quick and decisive destruction of the enemy. In such circumstances, attack should be directed not only against an enemy’s military forces, but also upon the resources which enabled it to wage a war, and the strength of an enemy’s will to fight, measured not only by the resolve of its leaders but also by that of the people themselves. At the same time, however, Clausewitz argued that war in any of its forms should be seen as a political instrument, and should only be embarked upon as part of a political strategy. Military action, he argued, was “simply a continuation of political intercourse” and its use should be conducted and restricted along “political lines”. Furthermore, there were instances when, for good political reasons, total war was not appropriate. Military action might well be limited to the occupation of a city or a piece of territory in order to force a favourable and peaceful settlement. And it followed that if war were a political act, then its ultimate direction should be in the hands of a country’s political leaders, with the military using their skills to fulfil the aims of the nation. ontrol of military strategy.

ontrol of military strategy.

xxxxxPedro, who was prepared to fight for a parliamentary system provided it remained under the authority of the Crown, at once sailed to Europe to raise an army against his brother. It landed near Porto in July 1832, but was besieged in that city for more than a year. In June 1833, however, a second force, supported by British troops, landed in the Algarve and captured Lisbon the following month, bringing an end to the War of the Two Brothers. Miguel went into exile in June 1834, Pedro died a few months later, and Maria de Gloria became queen as Maria II. Whilst in favour of some measure of liberalisation, she supported her father’s particular form of constitution and, despite continued political unrest, it was this pattern which generally remained in force in Portugal until the country became a republic in 1910.

xxxxxPedro, who was prepared to fight for a parliamentary system provided it remained under the authority of the Crown, at once sailed to Europe to raise an army against his brother. It landed near Porto in July 1832, but was besieged in that city for more than a year. In June 1833, however, a second force, supported by British troops, landed in the Algarve and captured Lisbon the following month, bringing an end to the War of the Two Brothers. Miguel went into exile in June 1834, Pedro died a few months later, and Maria de Gloria became queen as Maria II. Whilst in favour of some measure of liberalisation, she supported her father’s particular form of constitution and, despite continued political unrest, it was this pattern which generally remained in force in Portugal until the country became a republic in 1910.